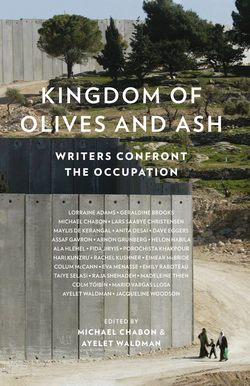

Читать книгу Kingdom of Olives and Ash: Writers Confront the Occupation - Colm Toibin, Ayelet Waldman - Страница 10

GIANT IN A CAGE MICHAEL CHABON 1.

ОглавлениеThe tallest man in Ramallah offered to give us a tour of his cage. We would not even have to leave our table at Rukab’s Ice Cream, on Rukab Street; all he needed to do was reach into his pocket. At nearly two meters—six feet four—Sam Bahour might well have been the tallest man in the whole West Bank, but his cage was constructed so ingeniously that it could fit into a leather billfold.

“Now, what do I mean, ‘my cage’?” He spoke with emphatic patience, like a remedial math instructor, a man well practiced in keeping his cool. With his large, dignified head, hairless on top and heavy at the jawline, with his deep-set dark eyes and the note of restraint that often crept into his voice, Sam had something that reminded me of Edgar Kennedy in the old Hal Roach comedies, the master of the slow burn. “Sam,” he said, pretending to be us, his visitors, we innocents abroad, “what is this cage you’re talking about? We saw the checkpoints. We saw the separation barrier. Is that what you mean by cage?”

Some of us laughed; he had us down. What did we know about cages? When we finished our ice cream—a gaudy, sticky business in Ramallah, where the recipe is an Ottoman vestige, intensely colored and thickened with tree gum—we would pile back into our hired bus and return to the liberty we had not earned and were free to squander.

“Yes, that’s part of what I mean,” he said, answering the question he had posed on our behalf. “But there is more than that.”

Sam Bahour took the leather billfold out of the pocket of his dark blue warm-up jacket and held it up for our inspection. It bulged like a paperback that had fallen into a bathtub. When he dropped it onto the tabletop it landed with a law book thump. It was a book of evidence, proof that the cage he lived in was neither a metaphor nor simply a matter of four hundred miles of concrete and razor wire.

“In 1994, after Oslo,” Sam said, “my wife and I decided to move back here.” They had been married for a year, at that point, and decided to apply to the Israeli government for residency in Palestine “under a policy they called family reunification.” He flipped open the billfold and took out a passport with a familiar dark blue cover. “As an American citizen, I entered as a tourist, on a three-month visa.”

Sam Bahour was born in Youngstown, in 1964. His mother is a second-generation Ohioan of Lebanese Christian descent; his father emigrated to the United States from the town of al-Bireh, then under Jordanian control, in 1957. After spending a few unhappy years working for relatives as a traveling salesman in the rural South (“Basically a peddler,” in Sam’s words, “selling cheap goods to poor people at like a two hundred percent markup; it really bothered him”), Sam’s father settled in Youngstown, with its sizable Arab population. He bought the first of a series of independent grocery stores he would own and operate over the course of his career, got married, became a citizen, had a couple of kids, worked hard, made good.

A few things Sam said about his father seemed to suggest that though the elder Bahour settled and prospered in Ohio, he did not entirely lose himself in the embrace of his adopted country. When Sam was born his father had named him Bilal, after the most loyal of the Prophet’s companions. But when non-Muslim neighbors in Youngstown shortened Bilal to “Billy,” Sam’s father—whose name was the American-sounding but authentically Arabic Sami—had his young son’s name legally changed to match his own. The freedom to return home that an American passport would afford, if only for three months at a time, had been among his motivations for marrying Sam’s mother and becoming a naturalized citizen. Some key part of the man—words like heart, mind, and spirit are only idioms, approximations—never left the house on Ma’arif Street where he had been born and raised, in the al-Bireh neighborhood of al-Sharafa, which belonged not to the Ottomans, the British, the Hashemites, or the Israelis but only to the people who lived in it.

“I was brought up in a household that lived and ate and slept Palestine,” Sam would tell me, a couple of days after our first meeting over ice cream at Rakub’s. “I lived in Youngstown, where I didn’t know most of my neighbors, but I could tell you everybody in my neighborhood here in Ramallah. That’s an odd kind of way to grow up.”

That enchanted blue American passport, part skeleton key, part protective force field, could work powerful three-month spells, both for Sam’s father and for Sam, once he and his Jerusalem-born wife, Abeer Barghouty, decided to try to make a life in al-Bireh. For thirteen years after his application for a residency card under the Israeli-controlled family reunification policy, Sam raised his daughters, built a number of businesses (telecommunications, retail development, consulting), worked for himself and his partners, for his clients and for the future of his half-born country, and lived a Palestinian life, all in tourist-visa tablespoonfuls, ninety days at a time. But in 2006, for reasons that remain mysterious, the magic embedded in his US passport abruptly ran out. Returning to the West Bank from a visa-renewing trip to Jordan, Sam handed over his passport to an Israeli border officer, expecting the routine ninety-day rubber stamp. But when the passport was returned to him Sam saw that alongside the stamp, in Arabic, Hebrew, and English, the officer had handwritten the words last permit. Once this final allotment of ninety days ran out, Sam would no longer have permission to stay in the West Bank or Israel, and when he left—left his home, his family, his business, his community, and everything he had worked to build over the past thirteen years—he would not be permitted to return.

“So I lobbied at very significant levels,” he explained, flipping to the passport’s back pages, “but they were only able to get me renewals—somebody got me two months, somebody got me one month. Very troubling. And then out of the blue I got a call … and they say, ‘Your residency card has been issued.’ I applied in 1993, the call came in 2009. I said, ‘Oh, yeah, I did apply, I remember.’”

He rolled his eyes upward in a pantomime of searching for a dim and ancient recollection, reenacting the moment. He waited, inviting us to find comedy in this epic feat of bureaucratic sluggishness, showing us that he maintained a sense of humor about his predicament, the way you might maintain a vintage car or a gravel road. It required diligence, effort, and will.

“So they say, it’s been issued, come down to the office and pick it up. And bring your passport. And I hung up the phone and I told my wife, ‘This is problematic. What do they want with my passport?’ Because like you, I travel a lot, and I actually read the fine print.” He turned to the fifth page in his passport, where the bearer was reminded that his passport was the property of the US government. “This isn’t ours. This is the State Department’s. So it’s not mine to give to anybody. But I took a chance. I took my passport, I drove my yellow-plated car to this office.”

One of the first things a visitor to the West Bank learns to notice is the color-coding of vehicle license plates. On cars owned by Palestinians they are white; the plates of Israelis (or licensed tourists) are yellow. Yellow gives drivers access, in their brand-new Hyundais or Skodas, to a system of excellent highways that bypass and isolate the towns and villages of the occupied, with their white plates, and their older cars, and their pitted blacktops thwarted by checkpoints and roadblocks. For the sixteen years of his life as an American tourist in the West Bank, Sam drove a car with yellow plates.

“So I give the lady my passport.” He flipped through the pages till he reached a stamped and printed label some clerical hand had pasted in at the back. “It took two seconds. They stamp it, and they say, ‘Congratulations, here’s your ID.’ First, I look, I say, ‘What the fuck did they just do to my passport?’” He turned to one of the Israelis in our party. “You read Hebrew, I don’t, but I know it says, ‘The holder of this passport has been issued a West Bank residency card.’ And they take the number of my residency card, and they place it here, in my American passport. Let me tell you what that means. It means that for all intents and purposes, this lady with her stamp has just invalidated my American status here. Because say I get in the bus with you now, and go back to Jerusalem, and a soldier finds this stamp? He’s not going to find a visa anymore. He’s going to say, ‘Wait a minute. You’ve been identified as a Palestinian in our eyes. Where’s your ID?’

“At this point I have three options. One, play stupid American, I don’t know what you’re talking about. What do you mean, ID? Not too smart, they take my passport, look at the ID number here, enter it on the computer, turn the screen around, and say, ‘Does that person look familiar?’

“The second option: ‘I’m sorry, Officer, I forgot my ID at home.’ Not smart. Anybody that’s been issued an ID, especially if you are a male, has to have it with him at all times. Without an ID, I can be administratively detained for six months.”

Administrative detention—imprisonment without charge or finite term—is among the most feared of the specters stalking everyday Palestinian life. The Fourth Geneva Convention, the finest flower of the Nazi defeat, strictly and explicitly forbids it, except under the most extraordinary circumstances. One may safely assume that in the view of the convention’s drafters, having left one’s ID in one’s other pants would likely not merit the suspension of habeas corpus.

“So, third option, let’s say I show this officer my ID.” From the billfold he now took out a bifold plastic case, dark green, and unfolded it to reveal his identity card behind its clear plastic window. It looked like a typical driver’s license or photo ID, thumbnail headshot of Sam, text printed Hebrew and Arabic characters, moiré of anticounterfeit security printing. “He opens the ID, what does he find? Arabic so we can understand, Hebrew so the issuer can understand. It has my place of birth, my date of birth, my religion—for some reason—and: what’s my cage.”

Most of us understood that he was joking, but it seemed like an angry joke. After a pause, there was a chuckle or two around the table.

“Actually it doesn’t say cage, it says place of residence. But there is no part of area A”—Sam was referring to the archipelago of major Palestinian population centers that has been strewn by Oslo II across the sea of occupation—“which is not an open-air cage, surrounded by fences, walls, checkpoints, military installations, et cetera. So I’m from the cage of Ramallah, actually it says the cage of al-Bireh, very precise. It means I can’t be in the cage of Gaza, but Gaza is just as occupied. I can’t be in the cage of East Jerusalem, but East Jerusalem is just as occupied. I can’t even be in forty percent of the Jordan Valley, which is off limits to anyone who doesn’t live in the Jordan Valley.

“So there I am, in the office, with this new little stamp in my American passport. I can’t use the airport, I can’t go to Tel Aviv University, where I used to be a graduate student, even though as a US citizen, getting my MBA there, I had no problem going and coming. I went back to my car, and I thought, Do I take my car home? Or do I take a taxi? Why would I say that, right? It’s my car. It belongs to me, I paid for it with my money. Why? Because anyone that has one of these”—he pointed to the stamp again—“is not allowed to drive a yellow-plated car.

“And now, all of a sudden, I start to feel what it’s like to be a full-scale Palestinian.”