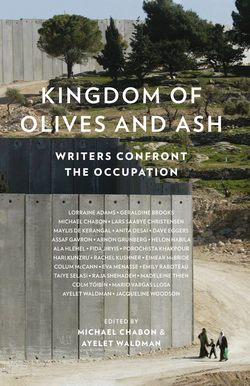

Читать книгу Kingdom of Olives and Ash: Writers Confront the Occupation - Colm Toibin, Ayelet Waldman - Страница 15

6.

ОглавлениеI had heard that Nablus, in addition to its soap, was known for its excellent kanafe. This is a traditional Ottoman pastry, similar to baklava but filled with cheese and wrapped in honey-soaked shredded wheat instead of phyllo. Before Sam and I returned to Ramallah, he said, he would take me to get some kanafe; he knew a good place. But before he could make the correct turn on the road coming back from the soap factory, we came upon a checkpoint that Sam had not been expecting.

A couple of IDF soldiers stood at a fork in the road, squinting in the bright sun, pallid young men with Tavor assault rifles slung over their shoulders looking, like so many Israeli soldiers, as if they had gotten dressed in a dark room and put on someone else’s uniform by mistake. I had seen bored young men before—I had been a bored young man—but these guys took the gold. I was reasonably sure they were not going to shoot me or Sam, but if they did at least it would keep them awake. To get me to the promised kanafe, Sam wanted to take the right-hand fork; one of the soldiers—he looked to be about twenty, and the elder of the pair—told Sam, in Arabic, that he would have to take the left. The soldier’s tone was curt but not hostile. It bordered on rudeness but he was too bored, for the moment, at least, to step across that border.

“I have a foreigner with me,” Sam said, in Youngstown-accented English. “Why can’t we go to the right?”

I was oddly relieved that Sam didn’t mention the kanafe. Pastry did not seem like an adequate reason to irritate a heavily armed man. The soldier repeated, in Arabic, that Sam would have to go to the left and, in a more helpful tone of voice, he added something in Hebrew. After that he repeated the original dull formula, in Arabic: we would have to go to the left. Meanwhile a car with white plates was coming along the forbidden road from the other side of the checkpoint. The soldiers waved it and its Palestinian driver through without any show of interest, or even attention. That was when Sam did something that seemed to catch the older of the two soldiers by surprise: he asked why.

“Why can’t we go to the right?” Sam said. “What is the reason?”

The soldier roused himself from his torpor long enough to shrug one shoulder elaborately and give Sam Bahour a look in which were mingled contempt, incredulity, and suspicion about the state of Sam’s sanity. It appeared to have been the stupidest, most pointless, least answerable question anyone had ever asked the soldier. What kind of dumbass question is that, Shit-for-brains?, the look seemed to say. “Why?” How the fuck should I know?

The soldier had no idea why he had been ordered to come stand with his gun and his somnolent young comrade at this particular fork in this particular road on this particular afternoon, and if he did, the last person with whom he would have shared this explanation was Sam. That was what the look said, in the instant before it vanished and the proper boredom was restored. We went left.

“What did he say, in Hebrew?” I asked Sam, after we had been driving away from the checkpoint, in silence, for almost a minute. The silence on Sam’s side of the car endured for another few seconds after I ended mine. When Sam finally spoke, the strangulated Edgar Kennedy tone of restraint in his voice was more pronounced than ever.

“He told me—such a helpful guy—that this road would take us to the very same place as the other way, to the road back to Ramallah. Which is true, except we’ll hit it much farther along, and we won’t go past where we can get you your kanafe.”

I reassured Sam that I could live without kanafe. I tried to make a joke of it—my jones for kanafe, another victim of an unjust system—but Sam didn’t seem to be listening, or in the mood for laughing, just then. I had a sudden realization.

“Wait,” I said, “is the other road blocked at the far end, too?”

“Of course not,” Sam said. “You saw the car? They’re letting people through from that end.”

“So we could, hold on, we could just take this road to the Ramallah road, then backtrack to that other road a little way, and then come back to where the kanafe is from that end?”

“We could drive all the way back to the checkpoint on that road, and come up right behind those two guys, and then we could beep the horn, and say, ‘Look, here we are!’ And then turn around and go back. And it would be just like they had let us through the checkpoint. Except that it took forty-five minutes instead of ten.” He laughed. It was an irritated-sounding chuckle, and it was followed by another silence. The checkpoint and the soldiers had definitely spoiled Sam’s mood.

There had been times, Sam said, at the end of the long pause, at other checkpoints, when he had actually enacted the above-mentioned scenario of circumvention, including the defiant beep, just to point out to soldiers manning a roadblock how useless, pointless, and arbitrary their service was. I wondered how much more irritated he had been on those days than he was right now. Irritated enough to give in, at that level, to futility.

Because of course, I thought, pointlessness was the point of the roadblocks that forced you to make a stop at Z on your way from A to B. Pointlessness was the point of the regulations forbidding access to cellular bandwidth that everybody had access to, of the Byzantine application process to get a permit for a ten-mile journey that would take all day, even though everyone knew that the permit would automatically be granted, except on those days when, for no reason, it was denied. We tend to think of violence as the most naked expression of power but—of course!—at its purest, power is fundamentally arbitrary. It obliges you to confront the absurdity of your existence. Violence is just another way of doing that.

I tried to return our conversation and the remainder of our time together to an earlier, less infuriating and humiliating portion of that time. I told Sam how much I had enjoyed meeting Mr. Tbeleh, how encouraging it was to see that a single-minded and determined individual could, through hard work and a touch of obsessiveness, overcome all the difficulties and indignities of the occupation, and find a way to thrive. I was talking about Mr. Tbeleh, but I was probably thinking of Sam, too. I shared with him the sense that had occurred to me, over and over again in East Jerusalem and the West Bank, that the Palestinians were not going anywhere. Listening to Mr. Tbeleh, I said, had aroused the same certainty in my mind. He and his soap factory were proof of and testimony to the resilience of the Palestinian people.

“Yes,” Sam said gravely. “That’s our problem. We’re too resilient. We can adjust to anything. You put up a roadblock for a while, everybody complains, but then they get used to it. And then when you take it away, they say, ‘Ah! Progress!’ When all it is, they just got back what they always had a right to, and nobody should have ever been able to take it away from them. That isn’t progress at all.”

I thought about that, about how much reassurance I had found in the soap factory and in Mr. Tbeleh. Obviously a Palestinian could find reassurance there, too. Look, the soap factory says, it’s bad, it’s even very bad, but it’s not all about administrative detention and collective punishment and bulldozed olive orchards and helpless, wounded men shot dead in the street. The soap factory said that if you just kept your head down and focused on soap, if you loved soap, you could just make soap; and it would be excellent soap. You would be able to sell it to the Italians and the Japanese. Maybe one day you might sell it at Whole Foods, the way Canaan Fair Trade, a firm in the city of Jenin, does with its olive oil. You could have 3G, or 4G, or 5G. You could have a nice place to drop your kids while you shopped for yogurt from Israel, Nablus, or Greece. You could get from point A to point B, as long as you were willing to go through point Z, forty-five minutes out of your way, for no reason other than it served Israel’s purpose to force you to accept a pointless forty-five-minute detour. As long as you were willing to accept, consciously and unconsciously, the arbitrariness that governed every aspect of your life, you could actually get something done.

Suddenly I felt that I understood something that had puzzled me, so far, about the career of Sam Bahour. In objective terms, Sam had prospered at every business he had undertaken, and at every project he had put his hand to since coming to Palestine in 1993. And yet at key moments, it seemed, at the peak of success, at the moment of accomplishment, he had parted ways with his partners or investors. He had set the cup of triumph aside, stood up, and left the table. I had wondered about this all afternoon, but as we drove away from the pointless checkpoint, I thought I understood. In a Palestinian life there were checkpoints everywhere—crossroads, real and figurative, where you were obliged to confront the fundamental futility, under occupation, of any accomplishment, no matter how humble or how splendid, from opening a multimillion-dollar glass shopping plaza in the midst of a violent uprising to restoring your village’s access to its ancestral water to keeping your child alive long enough to graduate from Birzeit University.

When Sam said that Palestinians’ problem was being too resilient, I saw that accomplishments of this nature—accomplishments like Sam’s—were not merely futile; secretly they served Israel’s strategic goals. They lent the color of “normal life” to an existence that every day deliberately confronted four and a half million people with the absurdity of their existence, which was determined and defined by the greatest sustained exercise of utterly arbitrary authority the world had ever seen. Under occupation, every success was really a failure, every victory was a defeat, every apparent triumph of the ordinary was really a gesture empty of any significance apart from reinforcing the unlimited power of Israel to make it. That, more than any roadblock, checkpoint, border fence, or paper labyrinth of permits and identity cards, was the cage that Sam Bahour lived in. It was the limit of every reach, and the ceiling that he bumped against every time he tried to stretch himself to his full height.

“He does love soap, though,” Sam Bahour conceded, thinking back to our meeting with Mr. Tbeleh, in his tidy little kingdom of olive oil and ashes. “He really, really does.”