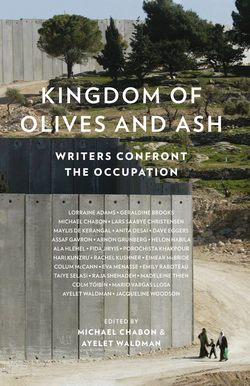

Читать книгу Kingdom of Olives and Ash: Writers Confront the Occupation - Colm Toibin, Ayelet Waldman - Страница 19

CITIES AND NAMES (2)

ОглавлениеIn 1983, Susya, the Israeli settlement, was established next door to the Palestinian village of Susiya. Under international law, the settlement is in violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention, in which an occupying power cannot transfer civilian population to an occupied territory, and is considered illegal. The Israeli government is the only government in the world that disputes this illegality, despite a ruling of the International Court of Justice. In a 2015 report submitted to the Netanyahu government, the settlers’ NGO, Regavim (“Patches of Soil”), a right-wing organization whose stated mission is to “preserve Israel’s national lands,” calculated that Jewish settlers had built 2,026 structures on private Palestinian property. Back in February 2012, Regavim had petitioned the Israeli Supreme Court to expedite the demolition of Palestinian Susiya, claiming that it was an illegal outpost, a petition that is, as of this writing, very much ongoing.

The Israeli government contends that all structures in Palestinian Susiya have been built without permits and are therefore illegal and subject to demolition. The settlers believe that the South Hebron Hills are part of the biblical heartland of Judea and Samaria, a currently “empty area” that belongs to the Jewish state. Yochai Damri, the chairman of the Har Hevron Regional Council, told the UK Independent that it was not the settlers who were newcomers; rather the villagers of Palestinian Susiya had arrived only fifteen years ago. He concluded, “These are criminals who invaded an area that doesn’t belong to them.” The surrounding land allocated to Israeli Susya by the government is now ten times the size of the settlement itself.

Driving in the West Bank, along a Route 60 altered to provide a highly modern and convenient highway between the settlements, and along which, for long stretches, Palestinians were once forbidden to travel (funneled instead to a network of narrow roads slowed by detours, checkpoints, and barriers, a system the Israeli government named “the fabric of life”), I find it frankly impossible to remember that I’m in Palestine. When we visited the settlement of Kiryat Arba and were confronted by hostile settlers, a man, who proudly told us he had relocated from France five years ago, cried out to his companion, “Ask her where she thinks she’s standing! Is she in Israel or Palestine? Then you’ll know whose side she’s on.” I did feel then that perhaps I shouldn’t be standing in his park, which contained a memorial celebrating Baruch Goldstein, who in 1994 walked into a place sacred to both Judaism and Islam, the Cave of the Patriarchs (Hebrew), also known as the Sanctuary of Abraham (Arabic), and opened fire in a room that was being used as a mosque, killing 29 Palestinians and wounding 125. I was relieved to depart. The police station here in the settlement of Kiryat Arba is where a Palestinian from the South Hebron Hills must come if she or he wishes to report a crime.

From Route 60, there are two signs, one for Susiya, the archaeological park; and one for Susya, the settlement. There are almost no road signs for the Palestinian villages. Israeli Susya should feel optimistic about its future prospects. The government has offered Palestinian Susiya a piece of land near the boundaries of Yatta (population sixty-four thousand), which would effectively move them into Area A, where more than 90 percent of Palestinians live. I have written earlier about the difficulty of aligning what one reads on a map and what one observes on the land and roads themselves, but there is one important detail in which both suddenly cohere: the highly populated Areas A and B are the cramped spaces of Palestinian life. Home to more than two-and-a-half million Palestinians, and including the cities of Ramallah, Hebron, Bethlehem, Nablus, Yatta, and others, it has been subdivided into 166 separate units that have no territorial contiguity. In other words, they are like shattered glass. Encircling each shard are long lines of Israeli settlements. Where the shape of Palestine, according to the Green Line, once appeared like a broad river, now it is a handful of pools, cut off from one another, slowly evaporating. Palestinian Susiya is a droplet being diverted into the nearest pool.

I spent a night in Palestinian Susiya, gazing up at Israeli Susya. I had some childish idea that, from this holy and beautiful landscape, I would see the immensity of the sky and the blanket of stars. As night fell, I sat on the rocky escarpment with Nasser’s son, Ahmed, who attempted to teach me to count to ten in Arabic. His father scrolled idly on his phone. The two places, Susya and Susiya, are literally one above the other. I could walk uphill and be in Israeli Susya within five minutes. Around us, dogs barked. The voices of women came and went. The evening sun diminished and was gone.

All night, Israeli Susya glowed. Its houses, perimeter roads, and guard stations, connected to the electricity grid, were powerfully, warmly lit. Palestinian Susiya, meanwhile, deemed illegal, was barred from connecting to the power supply. Its electricity came from solar panels donated by a German NGO and installed by an Israeli NGO, its water filters from Ireland, also installed by an Israeli NGO, its medical clinic from Australia, and its school from Spain, resulting in an unlikely cosmopolitanism. Prior to the solar panels, villagers would go to the town of Yatta to charge their phones. The visual contrast was crushing: light above, dark below. The future, the past. Safety, the wild. I couldn’t make out the stars. The sky was too well lit, as if we were on the outskirts of a bustling American town.

I fell asleep reading Calvino by the light of my phone—“It is the desperate moment when we discover that this empire, which had seemed to us the sum of all wonders, is an endless, formless ruin”—and his description of the city of Berenice, whose just and unjust cities germinate secretly, ad infinitum, inside one another: “all the future Berenices are already present in this instant, wrapped one within the other.”

Earlier in the day, when I asked Nasser’s father what he hoped for, the elderly man had answered, “I wish not to be woken in the night to have my home demolished.” Unsurprisingly, I slept fitfully. I curled up as small as I could on my mat, in the room I shared with the elderly man and Nasser’s two small sons. All night, the dogs of Palestinian Susiya howled and barked, as if to warn something off, or as if perplexed by their own existence. My dreams clung to this broken sound. I opened my eyes, exhausted, to the sound of Nasser’s wife, Hiam, going out to tend the chickens and the sheep, and to bake the daily bread in the communal taboon, the earth oven.

I got up. On our knees, we mixed feed for the sheep. My notebook fell into the dirt, fluttering stupidly, and my pen rolled away. My grandparents, too, had been villagers. They fled war and poverty, but my grandfather could not escape, and was executed by Japanese soldiers during the Second World War. My father had been five years old, but he survived this devastation that claimed thirty-six million lives in Asia alone. The things I tried to see here seemed cloaked from my eyes, as if I walked in a hall of mirrors, surrounded by conjoined cities with the same destiny. As the morning wore on, Nasser’s son led me through the chores, including the milking. Ahmed was so full of goodwill and curiosity it broke my heart. Here, he would say, using every bit of English he possessed. Come here. He smiled as I photographed him holding fast to a sheep. Eat, he said to me. He brought me bread, sheep’s milk, a little hummus, an egg. I learned another word, baladi. The taste of the village and the earth.

Above us, the high-wattage security lights of Israeli Susya were dimming. Here, in the other Susiya, the solar panels were not functioning, and there would be no electricity this morning, but in the crisp morning light, everything could be seen. All the invisibilities were laid bare.