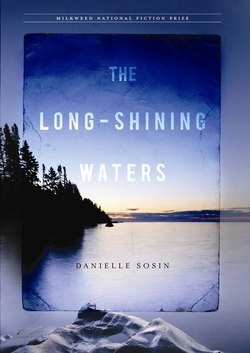

Читать книгу The Long-Shining Waters - Danielle Sosin - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1902

The white-maned waves rise and fall, cascading toward shore in carousel lines. Rumbling spray and muffled thunder. Knuckled legs churning and watery hooves, kicking up whorls of sand. Every edge rough washed. Every sharpness worked smooth. Rock. Wood. Bone. Glass. Frothing necks riding blue water breach and then sink back again, plunging headlong into roundness.

A cove of smooth grey stones, soft and flat and sun warmed against her cheek. They press into her ribs in hard sickles. Ear to rock, she can hear their hoofbeats, can feel the vibration in her bones. Warmed hair, frigid spray from the lake, cool wind, and the gulls flying stiff winged.

They cascade toward shore in carousel lines.

Cool on her arm. Cold. Her arm’s cold. Berit draws it under the quilts and holds it between her legs. No more wild wind, no hoof-driven waves. She rises to her elbow and stretches. The air smells of ash. The fire has dwindled. Out the window is a wide, pale winter morning. With Gunnar at the lumber camp, the fire is solely her duty. Again, she has slept past stoking time. She throws the quilt over her head, warm in her dark cocoon.

Another week and he should be back. She slaps the quilt down and jumps to the floor, icy on the soles of her feet. The coals are still hot so the new logs flare. She adjusts the flue and is back in bed, pulling the warm covers around her. The crackling wood is a friendly presence, a certain kind of company.

Her sketchbook lies on the chair where she left it. If she’d propped it up when she fed the stove, she’d be able to see it from the bed. She’s working on a sketch of bears, trying to do it from memory. The new wood whistles and pops. Drawing is the one thing that saves her, it has since she was a girl. She’d have come unhinged without it, eleven years old and bedridden for months.

She’d been cobbing for rock on the dump heap near the mine, drawn by the hope of finding missed copper. And though a feeling in her stomach had warned her, she ignored it and kept on climbing. The rest still remains a blur—the sliding and twisting, the ripping pain. There were two round clouds in the sky as she lay there, and the sound . . . bam . . . bam . . . bam . . . rhythmic and forever, of the stamp mill on the hill.

She filled the first sketchbook she was given, front to back, both sides of each page, and the cardboard cover as well. She drew pictures of everything around her: a wilting daisy in a tin cup on the bed stand; her leg, twice broken, propped on a folded quilt; the dark pine woods of the Keweenaw out the window.

If Gunnar could see her lolling like this. But the salt beef is in the lake and it’s time to haul it out. He would have his say about her cooking it when there’s still a bit of moose hanging in the cool-shed. She recalls the animal’s wary brown eye as she’d stood at the door, the bull in her sights, waiting for it to move from the garden, not wanting to drop it in her potatoes. It was her last, biggest, and easiest kill of the fall. Gunnar will squawk, but she’s saving the last of the moose for his return. In three leaping bounds Berit reaches her clothes, which she’d left to warm by the stove. She dresses quickly, last, her black skirt, which tents the warmth around her legs.

The snow is dropping straight, no wind, as she walks down the path with her buckets and auger. There are fox tracks on the lake that weren’t there the day before. They skirt the shoreline, cross over her rope, and climb the rocks just short of the point. The snowfall creates a leaden hush, and now and then floating slabs of ice clack together in the water. The skin of ice on the hole shatters with a swift poke. The weighty meat twirls at the end of the rope as she pulls it from the cold water.

Now the snow’s coming down in big fleecy clumps, and she’s shifting the weight of her load as she walks up the path, thinking about when she wants to start the beef boiling now that it won’t be too salty to eat, and then whether to have it ready for dinner or supper. It doesn’t seem to matter much when Gunner’s away. The ripped net in the fish house still needs mending, but there’s something about horses on the edge of her mind, and she lifts her eyes as if in search of them through the cottony curtain of falling snow where a man is standing, and fear combs up the back of her neck, and her feet slide out, and the buckets fall.

John Runninghorse stands over her with a startled expression, his head cocked, his black hair catching snow, holding dead snowshoe rabbits that dangle along the length of his leg. “For the love of God,” Berit blurts out. He lays down his stringer and offers her a hand, but she’s already scrambling to her feet, flustered and brushing snow from her coat. “Gunnar’s not here,” she says breathlessly.

He nods and moves past her on the path, gathering her empty buckets as he goes. What in heaven’s name is he doing at her place, showing up at this time of year? Berit’s heart slows to a dull knock, and she circles her wrist, which is going to be sore.

The snared rabbits lay stretched at her feet, fat clumps of snow gathering in their white fur. Fresh. She can tell as she lifts them, still pliable and swinging as she continues up the hill.

Again, she is startled when she sees the large snowshoes leaning against the cabin. It’s rare to see anything that she doesn’t know by heart, or that she didn’t set in place with her own two hands. She leaves the rabbits hanging from a nail by the door. Oh, what a stew she could make of them. Through the window, John’s a boulder crouched on the lake, a lattice of snow falling around him. She feeds the fire to get coffee started, then ties her good apron around her waist—not one of her everydays that she makes from flour sacks. It is hard to imagine why he’s come. It’s obviously not time to help set the anchor rocks. There isn’t even a pudding to serve. Just yesterday’s soup. That’s the best she can do. At least the sugar bowl is full.

Gunnar would want the best for John. He thinks the man is some sort of prince, though she has never understood why. Not that there’s anything wrong with him, it’s just that she feels uncomfortable in his presence. And it’s not because he’s Indian; she’s known Indians all her life, having grown up near them on the Keweenaw. She’s not like those women, the newly come-over, who are afraid they’ll be murdered in their sleep, their children stolen, and all manner of things.

“He knows more about this land than I could ever hope to.” That’s the kind of thing Gunnar says when he’s been around John. Once Gunnar told her that John knew a hundred different plants in the woods. “What they’re good for. When to get them. Sure, but he doesn’t think anything of it. In fact, he seems embarrassed about it. He says that in his grandmother’s time, everyone knew twice as many.” It’s hard for Berit to imagine these conversations, since John will barely meet her eye, much less talk, and Gunnar is shy with most anyone but her. The lid of the kettle starts to rattle, and now John’s coming up through the snow. He’s got the auger balanced over his shoulder, and her piece of salt beef cradled in his arm.

Berit raps on the window and holds up a coffee cup, but John passes without looking in. Before she knows it, he’s in the doorway, standing there in his heavy wool coat, mitts to his elbows, boots to his knees. Filling it. Though he’s not that tall. He’s broad, but that’s not it either. He’s one of those people that just seems bigger.

“Please come in. Sit down. Do forgive me. I just didn’t see you standing there . . . Of course, I wasn’t expecting anyone . . .” Her voice is babbling like a stream.

John nods and scrapes a chair from the table. She’s glad he chose the one facing the window, so she can stand behind him near the stove. She pours him coffee and offers sugar and a spoon, feeling the cold coming off of his clothes.

“What brings you?” She retreats back to heat the soup, a false cheerfulness in her voice. Here she’d been pining for someone to talk to and now she can’t seem to manage.

John tastes the coffee, nods, adds sugar.

Lord, the bed is still unmade. “I hope you like pea soup,” she says, moving the pot to the center of the heat. She’ll have to be careful when she ladles it up so as not to scrape the bottom where she burned it yesterday. “It’s not much, but I’ll get that beef boiling.”

When she turns she finds him looking at her drawing on the chair. His head bobs approvingly, and she feels a puff of pride. People have always been complimentary of her pictures. When they lived in Duluth she drew a series of cards in colored ink that some said she could sell if she wanted—deer bedding in the snow, pinecones, tumbling waterfalls. Someday she’ll paint. Have a palette of oils and be able to mix any color. She looks at John, then at her lead-drawn bear. John turns away with a funny expression.

“They’re black bears,” she says, picturing them painted on canvas.

He stirs his coffee.

“Well? What do you think?”

He lifts his cup and nods.

“No, tell me, what do you think?”

“Your bears don’t have tails.”

“What?”

“No tails.”

Berit takes the book from the chair. “Bears don’t have tails. I’ve never seen a bear’s tail.”

“Maybe you’ve only seen them from the front.”

“What kind of tail?”

“Small. Furry.”

She can feel heat rising on her neck. John sits gazing at the tabletop, as if there was something interesting there, a smile, she thinks, playing at the edge of his mouth. She certainly doesn’t see what’s amusing.

“Well, it’s a drawing from memory. I’ll have to wait until spring and see for myself. Honestly I can’t recall seeing a bear with a tail.”

“All the animals in these woods have tails. All the mammals, that is, except you and me.”

Berit carries her book to the nightstand, not really sure what she’s feeling. Why should she care what he thinks? He probably has never even seen a real painting. She certainly didn’t like the reference to her tail, or his, or that she doesn’t have one.

The soup is burning. Berit hurries to the stove and lifts the pot off the heat. She can only make the best of it. She ladles the steaming soup into a bowl. “So what brings you this way? You never did say.” There’s the false cheer again.

“Rabbits.”

“Rabbits?” She sets the bowl in front of him.

“That’s why I came. I’m delivering them from Gunnar.”

“Where? You’ve seen him?”

“He’s at the lumber camp, down by Swing Dingle.”

“Yes, I know, but . . . you were there?”

John is looking at the tabletop again. “I did some hunting for the camp and then for him, too.” He holds the soup under his chin and starts in, not seeming to mind the heat.

“Well, how is he? What did he say?”

“I agreed to dress the rabbits,” he says between spoonfuls.

“I meant for me. Any word for me.”

He eats like he hasn’t had a meal in days, scraping every bit from the edges of the bowl. Then he rises abruptly and produces a piece of paper that’s folded in a tight square.

Berit unfolds it to find a strange hand, neat and uniformly upright. My Dear, My Mrs., the message begins . . .

I’m sending John with some rabbit, as I know they’re your favorite.

“I don’t understand,” she looks up. “This isn’t Gunnar’s hand. He can barely write.”

“It’s mine.”

“Yours?” She looks at the neat rows of cursive, too late to cover her disbelief.

“Boarding school,” he says in a stony voice. But she has gone back to reading . . . as I know they’re your favorite. Be certain that I am thinking of you, my dearest. It is so odd to hear his voice in this way. Things are moving in good time, so I hope to be home as planned. Don’t consider saving any rabbit for me. I don’t want to find even a morsel left over . . .

John puts on his hat and draws the knife from his belt. He examines its edge and then slides it back in its sheath, watching Gunnar’s wife as she reads. Her pale skin, her thin frame, her hair the color of dried grass, bundled at the back of her head. He’ll dress the rabbits as he’d promised. “Don’t let her talk you out of it,” Gunnar had said. “She’ll go on about how she can do it herself.” Well, she’s not talking, she’s leaning against the cupboard, fully engrossed in the letter, and he needs to get back to his trapline if he’s going to make it back to camp and then home, if he’s lucky, before the week is out.

John closes the door on the cabin’s warmth and the earthy smell of pea soup. He lifts the rabbits from the nail, wondering what, if anything, she knows of the story Gunnar told him at the logging camp.

The telling has stayed strong in his mind, the heaviness in Gunnar’s voice, all the stops and starts as he seemed to search for words. They’d sat together in an empty log sleigh. There was a bright moon and the wind stirred the shadows, as the camp’s men snored and coughed. No, his wife doesn’t know about the dead man in the lake. It was clearly the first time that Gunnar had spoke it out loud.

John lays out one of the rabbits, and with a deft hand puts his knife to its fur. He makes his cut at the rabbit’s hind foot, then draws the blade up the inside of its leg. He’ll stretch the furs, give Gunnar’s wife the meat, and leave the entrails for scavenger birds.

Horse-stinger. Dragonfly. Oboodashkwaanishiinh. Predatory, of the order Odonata, meaning tooth.

They are of the most ancient creatures. Once they flew the skies as big as kites.

I knew them as sudden visitors. They’d alight on a seat plank or gunnel. Stay for a time. Fly off into the blue.

Their first life is in water. Their second in air. I see them transform on the floor of the lake. Each time shedding and growing a new skin. I follow them across the shallows. Try to join as they climb from the water, on a reed, a plank, a plane of rock.

But I know now.

Their path is not mine.

I watch through the wavering blue above as the dragonflies leave their last casings, crawl slowly out through the backs of their heads. Their black skins remain on the shore. Empty and weightless in the breeze.

They mate in winged circles, shining and airborne. Arching their bodies to form a wheel. Curving. The male clasps the female behind the head. This wheel. This ancient flying dance.

There is one who still feels the rhythm of our dance.

The particulars of my life are now hers to hold.

I take myself from these shining bright shallows. In search of something, yet I do not know what.

I move with the rhythm of the dragonflies.

They are here. Aloft in the water currents. The small. And their ancestors, whose long pulsing wings ripple the shadowy images. A luffing sail. A lost crate of lemons. A silver button tumbling to the lake bed.