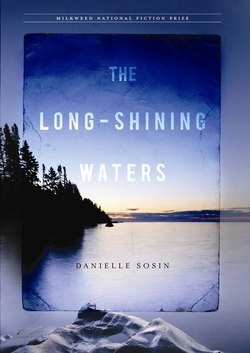

Читать книгу The Long-Shining Waters - Danielle Sosin - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2000

Nora reaches for the nail that holds the Christmas lights, her breath fogging against the mirror behind the bar, when something from her dream takes form, a feeling almost as much as an image, causing an empty swirling inside. She kneels on the bar stool and closes her eyes, hoping her mind might retrieve a scrap. But no. Nothing. It is usually like that, just a little sliver of something when she’s awake that had been part of something bigger. She moves her stool against the double-door cooler, bumping the new calendar that slides down on its magnet. January, again, already. The string of Christmas lights sags low—green, pink, yellow, blue—doubled and swinging in the barroom mirror as she lowers them from the nail.

There. She tugs her sweater down, her mood deflating at the sight of the mirror without the lights. They add a bright touch to the Schooner’s atmosphere, given the cold short days of a northern Wisconsin winter. Nora stands before the mirror, winding the string of lights. Her roots are starting to show again. She’s going to stick with the new copper color. It gives her more oomph than the brownish red. Reaching for her cigarette, she finds just a long piece of ash in the ashtray. It seems to always go like that, light one and get distracted or stuck at the other end of the bar. The clock reads 3:40 AM, bar time. Len won’t come to clean for a couple more hours.

There’s something about taking down Christmas decorations that always makes her feel empty. It’s like after the movies when the lights come on, the story’s done, and there she is, sitting with her coat in her lap. Sometimes she even gets the feeling at home in the silence of her apartment, after the TV twangs off.

Two by two Nora pulls bottles off the back bar to get at the strings of lights taped to the riser. The idea for the riser lights came years before, when her mirror swag fell in the middle of a rush. At the time, she was too busy to care, so she kept on working with the lights back in the bottles, and she grew to like the way they shone through. Pink in the vodka. A warm glow behind the brandy.

Well, it can’t be Christmas all the time, and cleaning’s the best way she knows to start over. The sharp smell of vinegar rises as it mixes with the steaming tap water. Nora pours herself a vodka, and with timing that is second nature, rights the bottle and reaches back, turning off the faucet.

Footsteps cross overhead, followed by the sound of a bench scraping across the floor. She smiles as she wrings the rag, then wipes the riser with long strokes, her attention on the ceiling, listening. Rose’s piano music drops down through the floor, slightly muffled and otherworldly. Angelic—the firm piano chords and the tinkly upper notes. The softest, sweetest sounds come from that tough old girl.

Nora hums and eyes the ornaments as she wipes the bottles and stands them back in place. The ornaments are everywhere—hooked into the netting that drapes from the ceiling with the glass floats and corks and the life preservers, hung from the rigging of the model schooner that’s displayed on its own shelf by the pool table. All around her, pieces of her history are dangling from thin threads. Nora swishes her rag in the bucket of water, wrings it, and wipes down the bottle of Crown.

The Indian girl with the papoose was a gift from Delilah, their best cook in the boom days, before the mines shut down. Those years were nearly fatal for the towns on the Iron Range. Superior got plenty bruised as well, with its railroad and shipping industry. But she’s not complaining, she’s been luckier than most. The last things to belly up in any town are its bars; well, its churches, too. She dumps the old water into the sink.

A waltz. The piano music feels just right as Nora pushes a chair around the floor, climbing up and down to get the ornaments from the nets. She unhooks the log cabin that Ralph, her late husband, made entirely of whittled sticks. Together for seven years, married for three. The cabin twirls in a circle from an old piece of leather. That’s twenty-four years she’s run the bar on her own.

She climbs down and sets the ornaments on a table. The silver angels holding hands like paper dolls. The elf on the pinecone from her sister Joannie in California, reminding her that she needs to mail a birthday gift. The old rusty red caboose. She’ll wrap them each in tissue paper and tuck them snugly in a box, like little children off to sleep.

Nora slides the chair up against the jukebox to get at the ornaments hung from the old bowsprit. The glass bird looks like it swallowed the pink jukebox light. It came in on a salty all the way from Greece. She smoothes the bird’s feathered tail between her fingers, then unhooks her daughter’s plaster handprint, painted green and red but only on one side. She’d thought about having her granddaughter make one so Janelle could hang them side by side on their tree. She’d even thought of making one herself, a trio going three generations. It was a good idea, but she never made it happen. They were barely in town long enough to open gifts as it was.

The music stops abruptly. The bench scrapes out.

Nora climbs down from the chair, holding the Santa straddling an ore boat that John Mack gave her. It’s been two years now, and the bar is still absorbing his death. When in port, he was a fixture—last stool on the left—always trying to start up his debate: Lake Superior, is it a sea or a lake? Telling his sailing stories to anyone who’d listen: sudden storms coupled with poorly loaded freight, nasty tricks played on green deckhands. She wraps the freighter in a piece of crumpled tissue paper, seeing his speckled blue eyes, how they’d draw people in as he spun his tales. Landforms changing shape. Strange sounds from the horizon. It’s still unbelievable that after years on those freighters, he fell out of his fishing boat and died of hypothermia. They found his body the morning of her fifty-fifth birthday.

The sky through the window is tinted orange from the glow of the neon Leinenkugel’s sign. Nora opens the door to the empty street and the steely smell of winter coming in from the ore docks. Lake Superior may bring in her business, but it’s heartless; you wouldn’t catch her on it for anything.

It’s snowing again, tiny flakes like salt, dropping through the streetlight halos. There’s not even a car to be seen, not a single black track on the street’s white surface. The tiny flakes drop down from the blankness, landing on her sweater and the toes of her shoes. The chimney on the VFW is a silhouette against the sky. There was something in her dream. She’s carried it all day.

Nora feels the cold air reach her lungs, feels the particular time of night where it seems like she’s the only one awake, the only witness to the snowy street, to the air blowing in from the frozen harbor, and the small falling flakes that are touching everything.