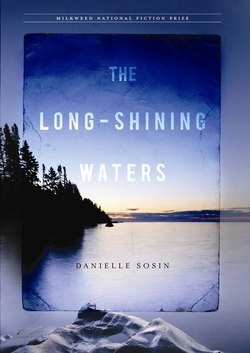

Читать книгу The Long-Shining Waters - Danielle Sosin - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1902

Gunnar straps on his skis, then hoists his pack. The warmer days are turning the snow wet and heavy, so the more distance he can cover before the sun rises, the better. He’s no stranger to the hour before night gives way to day, as he’s up and rowing to his nets as soon as the sky holds enough light to navigate. Sure, it’s not exactly the same in the woods. Woods cling to darkness longer than water.

He winds the scarf Berit knit around his face, straps his poles on his wrists, and shoves off. For a time he can follow the cuts of the logging sleighs, its snow-covered width discernable in the dark. The grade is downhill so he uses his edges, slowing to avoid scraps of bark that are large enough to throw him over.

It’s likely John got the rabbits to his Mrs. He can feel her on the other end of his journey, and he’d love to let loose and ski at full steam. But he has to keep from working up too much of a sweat. If the temperature drops suddenly it will freeze on him.

The woods are quiet except for the swish of his skis and the wool-to-wool of his pant legs. The lake isn’t visible, but its icy smell is in the air. He can feel it below like a sleeping animal, breathing its dark watery breath. It was quite a story that John had told him. A giant, twenty miles long and turned to stone, lying face up in the lake. He couldn’t quite follow the whole tale, or tell whether this Nana’b’oozoo was a man or a god. Maybe he was some type of Indian troll. Humanlike. Shape-shifting. In Aunt Dorte’s stories back home, trolls often turned to stone. John could have made the yarn up to distract him after his own grim tale, but that didn’t seem to be the case. He’d told it like it was true. It would be something to see, this Nana’b’oozoo, a sleeping giant in the lake.

The sleigh cut looks like a grey floor, laid along the bottom of a dark cave. No sign yet of the dawn. Gunnar loosens his scarf, already warming as he poles up an incline. It was good of John to hear out his story, not that he feels much better for the telling, not that it changes what he’d done. He reaches the top of the hill and takes the slope down, gliding past the indiscernible woods, keeping to the grey trail, as that day, indelibly set in his mind, unfolds before him in the darkness.

It was a fresh pine morning with rippling dark breakers, the lake still billowing from a two-day northwester, and he was worried about his catch. The northwesterly wind was still blowing strong enough to keep him from getting back to land. It finally let up late-morning, and so he launched his skiff into the lake. He rowed straight-lined away from shore, practically feeling Berit’s thick silence as she watched him through the windowpane. They’d fought. Sure. Well, not exactly. A small quip the night before and no words exchanged come morning. It was a pattern that had grown too familiar. Too many things had grown in place of the children.

The first stiffness left his shoulders as he worked the oars, his course taking him over familiar lake bottom—the basalt table that continues off his cove, with its high spot that he has to skirt, and the group of mammoth boulders, then the scattered few that are visible only when the lake lies flat, at five fathoms, still visible at seven, before the bottom drops away.

The air was crystal and sharp, smelling of pine pitch and rot, and the seagulls were crying loops in the air, following in hope of easy food. He positioned himself first by pine and stone face, then by the shapes of the familiar ridges. As he rowed, the land transformed itself as always from a stagnant footing, solid with home and wife, to an abstraction of shape and texture, a tool for navigation, and a goal that meant safety if the weather were to turn. He was hoping there’d been no damage to his gang, though the herring should be fine if he could get them in soon.

At the top of a swell, he spotted the red cloth fastened to his uphauler, then down he went into a trough, where there was nothing to see but water and sky. The swells were too big to bring her in standing, so he waited for the lake to lift him again, adjusted his course, and rowed on.

The gulls settled on the dark blue water, paddling back and forth, watching him work his ropes. “You best forget about it,” he addressed the flock. “I’ll not be tossing any storm herring today.” One more day of weather and the fish would have been ruined, gone so soft that bones would poke through their flesh when he went to pick them from the nets. Sure he gets tense when he can’t get out; he hadn’t meant to speak to her so curtly.

He started in at one end of his gang, hauling a section of net to the surface, lifting it across his boat, the cold water running from the ropes. One by one he freed herring from the mesh and dropped them into the bottom of the skiff. They were fine. The catch was fine. Too much time he could spend worrying.

When the section of net was cleared of fish, he pulled himself along below it, bringing a new section up and over, then watching the cleared one fall back to the lake, corks up, leads untangled. Everything was rolling and shining and wet as he rode up and down with the swells, the herring at his feet like sickle moons. He worked methodically, choking the fish in one section of net after another, his eyes moving from his task to the water, to the ridges, to the sky—always watching for weather.

A gull squawked and shit white in the boat as he started in on a new net. But something was wrong. The net resisted him. Its pull was skewed, and it wouldn’t come over the gunnel like it should. And sure if that net wasn’t one of his best. Not good. Not good at all. He hadn’t been able to afford new nets for some time. Maybe if he’d worked more of that year’s winter timber. But he couldn’t bring himself to leave, not with Berit so low.

He maneuvered himself further along, watching the net as he pulled it from the water, then the cleared side to make sure it sank back right. Could be that the lake had tossed a timber his way. The bulk of the problem was coming right up. There. A couple fathoms below, and it looked like a huge ball of a mess. Almighty. He couldn’t afford this. The weight of it was starting to strain, turning him so he was taking the swells at an angle. Then he stopped pulling. It lay below him in the water.

A man.

There was a man tangled in his net.

He rose and fell, rose and fell, and the sun shone and sparkled on the water.

A head and shoulders cocooned in the mesh. Black hair, or else some kind of cap. His thoughts raced nowhere and everywhere at once, like the blue sky and water that was all around him.

There was a man in his net. The fish lay in the bottom of the boat and the gulls bobbed on the water, watched with round eyes. He hauled the net closer to the surface. Something shone white. It was a hand. He felt his breakfast in his throat.

A man. A dead man. Wound in his net. He was wearing dark wool. If it was a uniform he’d never seen it. He pulled the straining net higher, and the body rose up and broke the surface along the skiff.

A white ear was sticking through the mesh. Water lapped at a waxy cheek.

He rose and fell with the body, feeling like he was in a dream. Even the fish at his feet looked unfamiliar. If he could wake and start the day over, open his eyes to Berit’s back. But it was no dream, sure as the cold in his fingers. He’d have to get the man into the boat.

The coat’s silver buttons were tangled in the net, and his leads were wound up and through. The man’s leg was bent at an ugly angle, but he couldn’t tell whether it was from his net or sometime before. Cutting him out would be the fastest, but he’d lose the net for certain that way.

He took hold of a cork to get a sense of what was what. The body shifted and the face rolled toward the sky. Black hair growing from a porcelain forehead. A mustache over lips like a bruise. His breakfast surged up again and he turned away. Water drops shed from the ropes, hit the surface in expanding circles.

He couldn’t afford to lose the net. He had no choice but to untangle him. He’d let the steamer know at the end of the week. He tried not to look at the face as he worked, unwinding the leads, tugging the net here and there. How long he’d been down was impossible to know, the way the lake holds things as they are, too cold for bloating gases, too cold to rot wood.

The buttons were impossible, so he cut them off the coat and let them sink out of view. A glint of light flashed as the body rolled. It was his other hand, his finger, a gold wedding band.

A gull paddled close, turned its head side to side.

Berit.

He couldn’t bring a body home to Berit. Already, she worried too much, feared for him in weather and not.

The white face stared up to the sky, unrelenting in its lifelessness. The most gruesome thing he’d ever seen.

He rode the swells.

She’d never forget it. He couldn’t bring the body in.

Would it be so wrong to leave him to the lake? Every man who had ever worked on the water had to come to terms with his own drowning there. There was probably a law, but who was to know. Laws were made for towns, for the problems of people who lived as close as stacked wood. They didn’t really apply to him. God’s laws were a different matter, but he hadn’t killed the man. He was dead when he found him.

He couldn’t bring the body home.

Using his knife as sparingly as he could, he worked steadily to release him, trying to block thoughts of the dead man’s wife, and focusing on his own instead. If it were he who had drowned in the lake, Berit would want to have his body. “Buried, not out there adrift,” she’d say. “Not left with the hope that you’d return.” But Berit knew, she knew. The lake’s a killer. She’d lived her entire life on its shores. She knew the water temperature didn’t bend toward hope.

The dead man’s wife was not his concern. He had a live one with enough sorrow as it was. He would not bring the dead man home. God forgive him. He couldn’t do it.

The sunlight shone innocently on the water, but the gulls, they were watching him closely. The net was damaged, though not beyond fixing. First, he decided, he’d take care of the body, then after come back and finish picking the nets. He’d tie him to the skiff and tow him further out.

When he reached down to get the rope around the man, he half expected his bones to poke through, but he was as solid as a cold side of meat. Gunnar tied the rope under the man’s arms, let out a length, and secured it to the skiff. There was no real reasoning to where he was going, just out deeper, one mile or four, he wasn’t sure when he’d stop.

A black head plying the waves. The body turning, showing the white face. Staring at the man was a danger to himself. He should have been watching the sky and the water, but putting himself in danger felt only right. He vowed to the dead man—or to God, he wasn’t sure—that from that day forward his life would change. He would coax his Mrs., his marriage, back to life.

Gunnar skis on as the sun lifts from the lake and is swallowed into a bank of clouds. He’d made good on his promise; their life has turned around. But still, he thinks of the man he left out there. His grieving wife. Maybe a passel of children. Not a day goes by when he doesn’t come to mind.

When the morning is well established, Gunnar stops to rest. He plants his poles in the snow and slides the pack off his back. He circles his shoulders and pops his neck, looking back toward the ridge he’d helped log, the sheared stumps and the bramble of brush. They’ll come through and burn what’s left.

Gunnar unscrews the cap to his canteen. As he drinks, the sun pokes out for a moment, causing a patch of water to brighten and then dim. He wipes his mouth across his sleeve, feeling small and fragile.

At fourteen, I crossed the ocean. The unpath’d waters. The deep salt sea. My feet solid on the ship’s deck, I imagined beneath the water surface. The fishes. The mammals. The corals. The algae. All the hidden dangers below. My face to the wind, I imagined exotic lands. Tried to grasp the great distances, and the endless horizon.

But the ocean was incomprehensible.

Too vast. Too far. Too deep, my mind said.

I had the luxury of giving up and turning my attention to other things.

As a man I worked the great Gichigami. Lake Superior. The sweet-water sea. I knew its waters touched no exotic lands. That its creatures were few. Dull colored. Benign. Still, like the ocean, its horizon is endless. I grappled as I stood on her shore, as I rode her waves in each morning’s light. But always I was left uncertain.

It is a fact that Superior is easily measured. In length. In width. In hundreds of miles.

Superior should be comprehensible.

It is not.

And that discord is readily felt.

The Great Lake is movement at peripheral vision. It is sound at the limit of audible frequency. It is the illusion of the ability to understand.