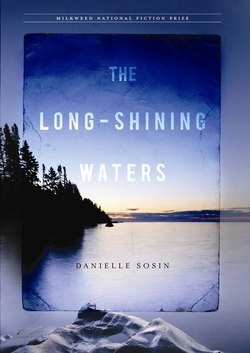

Читать книгу The Long-Shining Waters - Danielle Sosin - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1622

The river splits around a black rock with a white cap of snow before sliding back under the ice and over the little waterfall. Bullhead squats to rest for a moment near the small stretch of open water. There are two bubbling lines streaming out from the rock in a pattern the shape of flying geese.

Walking up from the big water has tired her. She had hacked a hole in the ice at a place that felt right, but there, as in her usual spots, the net had come up dripping and empty. Fish. Her mouth waters. Trout. Salmon. Whitefish. Herring. Cooking on sticks near a crackling fire. She would turn them slowly until they were done just right.

For two days they’ve eaten soup cooked from pieces of hide, lichen, and the stringy inner layers of bark. Night Cloud snared a rabbit, but it was small and shared mostly with Little Cedar. How proud Bullhead was of Standing Bird as he sat solemnly with his broth, the smell of cooked rabbit thick in the air, cramping her own stomach over and over with a desire more insistent than any passion she’d known.

A wind moves through the pines and they toss and creak, dropping small bits of snow to the ground. Little Cedar grows vulnerable. She has seen it many times before, the slowed response to what usually excites, and the dullness that settles over the eyes, like a snake as it begins to molt. She made a decoction of dried ox-eye root to give strength to the boy’s limbs, but its effect was mild. If only she’d had the root newly pulled, not dried. She could’ve chewed it and spit the softened bits directly onto his arms and legs.

The rock and water make a gurgling music, and the faint light plays in the streaming bubbles. Bullhead can hear Grey Rabbit working in the woods, her bone rasping against the high rock wall as she scrapes lichen to add to the soup. How quickly the soup leaves her stomach feeling empty, without even pumpkin blossom left for thickening.

Bullhead takes in a long weary breath. The air smells of old snow and open water. Across the river a chickadee sits perched on an icy limb. Its feathers are puffed around its body, causing its head to look small. Even the little birds make their own way, not nearly so weak as her kind, who are born without feathers, warm fur, or thick hide. She pulls off her rabbitskin mitt, looks at her fingers, the mean scar on her thumb. Yes, the Anishinaabeg were given the power to dream. And yet they are so fragile, so dependent, that they must take the very skins of other animals and wear them over their own to stay warm.

The chickadee sits puffed on its limb. The river water is dark, but also light in the places where it carries the color of the clouds. Bullhead follows the movement of the water. It slides in smooth sheets, circles and bends, wrinkling in lines that shrink and expand. Constant, constant. Constantly changing. Always the river, yet never the same. Slowly, the waters claim her, and her thoughts dissolve into the current. Gone is Bullhead, mother of three. Gone daughter, sister, clan member, widow. There is just the swift water as it twirls and glides, moves in smooth sheets that carry her downstream.

The sky lightens for a brief moment, illuminating Grey Rabbit’s hands and the patches of lichen, squash-orange and green, and then the light is gone and the rock face goes dull. Grey Rabbit looks to the sky as the long yellow crack in the cloud mantle passes, moving swiftly toward the big water. She must finish her work and get back to Little Cedar. She’d left him lying quietly by the fire, whispering to the cattail warrior in his hand.

Deep into the night she sits with him, willing herself to keep a close watch. But each night sleep overtakes her, and another child appears. The last was a girl, crying in her cradleboard. She disappeared into the woods, carried off by a creature made of ice.

Food. They need food. They had talked of moving on, in hopes of finding the animals in another place. Soon they will have to. Grey Rabbit rubs snow across her scraped knuckles, then wipes clean the long edge of her bone.

Bullhead makes her way toward the rasping sound. Her time at the river has soothed and calmed her, allowing her to see more clearly, to notice the wind-carved snow behind tree trunks, and the soft pink patterns in the bark of the red pines. “Ah, good.” She spots a dark vole in the snow, its feet curled and frozen, its head half eaten. She turns the rodent over in her hand, and drops it into the fish basket.

Her son’s wife looks small standing before the rock wall that rises from the forest. She has scraped a good amount of lichen already. She works hard every day, focused as a hawk, yet she stays as distant as one, too. Something troubles the girl. Something more than Little Cedar. Bullhead ducks below a snow-laden bough. She has tried sharing a number of stories about hunger, of times when she’d worried over her own children, but none of them have nudged Grey Rabbit to speak. She can only trust that the girl will confide if she needs.

“Don’t be so lazy.” Bullhead sets her basket on the ground. “Get those, up there.” She pouches her lips toward a high spot on the rock. “Those are the good ones. Those taste like beaver tail.”

Grey Rabbit smiles at the joke, though her smile fades when she sees what is in the fish basket.

Bullhead takes a scraping bone from Grey Rabbit’s bag and chooses a spot of her own to work. It’s an ancient rock with a solemn spirit, home to moss and lichen, and two small cedars growing out of a high crack. She places an offering at the base of the rock.

The two work in silence, tending their own thoughts, while their scraping falls into a shared rhythm.

Herring on a stick, slowly crisping near the fire. A line of herring, one more succulent than the next.

Little Cedar crying in his cradleboard, disappearing into the woods.

A bird’s call breaks the silence. It echoes off the high rock wall. Bullhead and Grey Rabbit stop scraping, and turn to meet each other’s eyes. Again, the bird calls, and they look to the trees, smiling at each other with growing delight. They search the bare limbs and the green pines for the one that cawed, black crow—whose return marks the coming of spring.