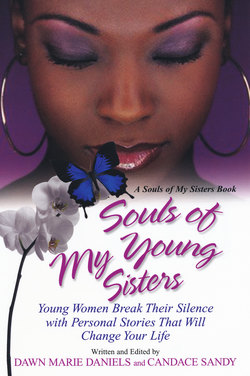

Читать книгу Souls of My Young Sisters: - Dawn Marie Daniels - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

FIRE AND WATER

ОглавлениеBy Ihotu Jennifer Ali

I love my parents. Truly I do. And I don’t say that just because I should, or because I grew up believing that is what good children should do, or because television and music and pop culture taught me what I came to view as normalcy between a mother and father and their daughter. I actually love them. But love is complicated.

I was born into a family of great love, and in fact, “love” in my father’s native tribal language was the name given to me: Ihotu. I was the eldest child, the pride and joy. And in the beginning, there was nothing but a love that was pure and simple. A love that drove my mother to follow my father from humble Minnesota to an equally humble Nigerian village where she endured lurking lizards and an unknown language and bathed her newborn child in public rivers. That love drove my father to also leave his family and return to the United States so that his children could experience the best education, one he had never known himself. That love also raised me to adore and mentor my two little sisters from the moment each was born. One, with mental and physical disabilities, I took under my four-year-old wing and loved her as if it were I, and not my mother, that had carried her for nine long months. An un-complicated love compelled my mom to fight, even though she despised confrontation, for the ones she loved. She fought with immigration officials to allow my father back into the country; she fought with doctors for the best care for her daughter and her special needs. Despite humble beginnings, my family was rich in love.

But love, even in its richness, eventually becomes complicated. It began with my parents. My dad is a Nigerian. This would have been fine, except that not even twenty-five years in the United States, an American wife and in-laws, and American friends—not even years of marriage and family counseling—could teach him what it is to be an American husband, or father. I have brief, gasping memories of him carrying me on his shoulders or dancing to Okanga drums to the sounds of “Sweet Mother,” and I admired his adventurous spirit and warm smile. Yet even I recognized a strained silence in the house. After years of abuse, neglect, and failed attempts at compromise, my mother finally ended it. She still loved him, even after he abandoned her and her children. My father became a distant memory, an occasional source of intense pain, and the impetus to my sister’s nightmares and my emotional detachment.

I loved my mother and admired her strength. She fought for me to stay in a school district I knew, after multiple moves and new faces and so many changes I could barely keep up. We kept moving, and I never bothered to unpack, yet at least I could stay in the same classroom, if not on the same street. She and my sisters rooted me to reality; wherever we were was home, and anywhere without them would be foreign. It was a comfortable existence, insular and safe, and we were enmeshed in a tight love—too tight, perhaps.

Then she started to falter. As I grew older she seemed to grow smaller, less capable, less aware. Increasingly wrapped in her own world, occasional men wandered in and out of our lives, and I earned the nickname of “mom” among my sisters. I took over when she wasn’t around, sleeping, unable to think clearly, or upset. In short, I took over. I love my mother, and I love my sisters, so I did what needed to be done for us. I was thirteen, and I began working, knowing that she would fall short for rent at the end of the month. And when she asked, apologizing and claiming each time would be the last time, I was neither surprised nor trusting. I knew we survived on the back of food stamps, community Christmas donations, and my hours on the clock or in the kitchen, rather than my hours in any classroom. When she took antidepressants for months, or spent weekends in the hospital, or threatened to commit suicide, I held her up and tried my best to show my sisters that nothing was wrong. I took over. I did this without regrets, because I loved them.

But over time, I realized the love they needed was more than just a shoulder to cry on, or a dependable hand that would prepare dinner or help with rent without complaint. At a certain point, I realized that I had given up myself entirely, for them. I loved them so deeply that I would sacrifice it all—my happiness, my health, my ambitions for a future career and family of my own—for them, and yet we were still only barely surviving. I had fallen into a life of such dangerous love that I was little better off than my mother, and my volatile emotions had been so solidly suppressed that I could no longer feel. I cared for her in times of sickness with the same passion that I recoiled at her inability to raise her daughters. I felt she failed me as a mother by not teaching me to be strong, yet her absence forced me into a role that forever defined my inner resolve.

One day, I decided to leave. The guilt follows me to this day, but I promised myself that I would begin to love myself as deeply and with the same reckless abandon that I loved my family. I am not gone forever—I call, write, and visit, and am still very much a part of their lives. However, I am not so enmeshed in love that I cannot see the future, cannot understand and learn from the past, and cannot even discern the difference. I love my parents deeply, but I do not want them to need me. I may never have the parents I see on television: the mother who checks in to make sure I’ve eaten my breakfast or the father who congratulates me on my new promotion. I don’t think I am abnormal; in fact, I’m sure many families are just like mine, when parents and children assume one another’s roles. But now, I play carefully with love, since I know it is made of both water and fire.

Ihotu Jennifer Ali is currently attending Columbia University in New York City, working toward a master’s degree in global public health with an emphasis on mental health and holistic healing methods. She has over four years of experience working with migrant and refugee women, communities of color, and community-based nonprofit organizations. She credits her faith, family, and love of words and music for her all her successes.