Читать книгу Of Bonobos and Men - Deni Ellis Bechard - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNaked Apes, Furry Apes, Godlike Apes

In an age when the state of the planet preoccupies us—from climate change to deforestation, and from the extinction of species to the degradation of human habitat—it’s hard not to wonder whether we are capable of working through lasting challenges. Do we have the cultural staying power, or will short attention spans, coupled with our love of instant gratification, doom our attempts to rehabilitate the environment, just as the naysayers have been predicting? Having read countless dismal news reports in recent years, I wanted to know about the sorts of people and projects that aren’t dominating the headlines, those developing long-term solutions to environmental destruction, their work done year in, year out, in all its routine and tiresome glory.

The Congo caught my attention early on because its rainforests are so crucial to preventing climate change, and because the country itself was at a crossroads. In 2003, it emerged from possibly the world’s most devastating conflict since World War II, and with increasing political stability, its massive forests and mineral wealth were again vulnerable to large-scale exploitation. Conservationists were rushing in, and of those working there, one group, the Bonobo Conservation Initiative (BCI), was fostering a surprising number of conservation areas in spite of its small size and limited funding. Two large community-based reserves had already been established and several others were in the works, all with the goal of protecting the habitat of the bonobo, a matriarchal great ape that, like the chimpanzee, has more than 98.6 percent of its DNA in common with humans.

When I contacted BCI’s president, Sally Jewell Coxe, and explained my interest in writing about new approaches to conservation, she described how she and a few others started the organization in 1998, in the spirit of bonobo cohesiveness, its goal to build coalitions so as to use resources more sustainably. Unlike national parks, the reserves contained villages whose occupants were trained to manage and protect the natural resources and wildlife. BCI’s model was inclusive, she said, inviting people in rainforest villages to participate and taking into account their histories, cultures, and needs in order to foster grassroots conservation movements.

This last detail caught my attention, that understanding another culture’s values had allowed BCI to develop a self-replicating conservation model. They focused on creating forums to discuss different ways of thinking about natural resources, and encouraging the local people to take leadership roles in conservation projects. Given that populations and the global demand for raw materials were soaring, that millions of hungry people were eager to cut down the Congo’s forest for farmland and hunt the remaining wildlife, a change of consciousness was as urgent as the application of environmental laws. The rainforest’s importance for life on earth was undeniably clear: it protected watersheds while releasing oxygen and removing carbon from the atmosphere. As for bonobos, they were already on the verge of extinction, their habitat only in the DRC, to the south of the Congo River’s curve, in an area where the national government’s influence barely reached.

The portrait that Sally painted of effective conservation work was a mixture of anthropology and conservation biology, in which knowledge of the land, the people, the animals, and the country’s history was essential. At the center of BCI’s vision was the bonobo. As one of humanity’s two closest living relatives, the bonobo was—Sally told me—important for our understanding of ourselves as humans: not only in terms of where we have come from and how we have evolved, but also in terms of what we can be.

Though I had read articles noting all that great apes might teach us about our evolution, none had said anything about how they could shed light on our future. They were often portrayed in simplistic terms. Bonobos were furry sex addicts that swung both ways, and chimpanzees waged war as best an ape could without modern weapons and the cold mathematics of organized armies. Gorillas were vegetarians, largely gentle despite gladiator physiques, and orangutans solitary forest creatures that paired up only for sex, a lifestyle that sounded uncomfortably similar to that of many writers. What those articles didn’t lead me to expect was the degree to which my research on bonobos would in fact change how I understood myself. While I would learn that their social structure did offer lessons in the origins of human nature, it also said a great deal about our potential, both as individuals and as a species, and the paths we might choose.

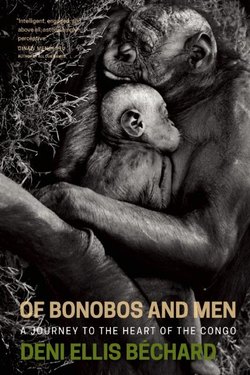

Just seeing photos of bonobos made a strong impression on me. They have lustrous black skin and red lips, black hair neatly parted in the middle and descending like muttonchops, flaring out proudly in the style of Martin Van Buren. But it was the way they looked at the camera that I found unforgettable. The bonobos’ eyes appeared curious and contemplative, unlike the often aggressive, guarded look I’d found common in chimpanzees. No doubt this was reductive and I had a lot to learn, but I saw in the gaze of the bonobo evidence of a deeply social being that, if it could speak, might have a number of questions for me.

Other photographs showed bonobos in a variety of familiar postures: lounging on their backs, one leg crossed over the other; or mating in the missionary position, muscles taut in their arms, the male grinning as if life couldn’t be better; or a mother standing, staring off, holding sugarcane, head poised on a stretched neck. With their long, slender limbs, they appeared so humanlike that, just to get a sense of proportion, I had to look up their weight: one hundred pounds for males—a little less than chimpanzees—and seventy for females. It was difficult to imagine such a close relative being hunted for the bushmeat trade, thousands slaughtered during the two Congo wars between 1996 and 2003, possibly as few as five thousand remaining.

Both because of their highly sexual nature and because one has never been witnessed killing another of its own kind, bonobos have recently become the stars of the great ape world. Even orangutan males, when battling over females, occasionally deliver fatal wounds, as do silverback gorillas. Gorillas sometimes kill infants, and for chimpanzees this can be a matter of course. Dominant chimpanzee mothers do away with the children of others, and males wage all-out wars, then slaughter the infants and take the females for their own, a description that reads like any of a million lines out of human history.

Bonobo society, however, is matriarchal. Females forge the alliances, and a male’s rank depends on that of his mother. When groups meet, males hoot but stand back while females cross over to one another in what may end up resembling an orgy. As for infanticide, it has never been witnessed; all bonobos in the group care for the welfare of their young. They have been nicknamed the “hippies of the forest” and the “Left Bank ape,” owing to where they live in relation to the Congo River. Unlike other great apes, they use a variety of sexual positions and often mate face-to-face, gazing into each other’s eyes. They enjoy oral sex and French kissing, and they make love for pleasure, comfort, or closeness, as a means of greeting, or just because they love each other. Sex is their hug, their handshake, their massage, and their noon martini. Sometimes, it allows them to defuse social tension, minimize violence, and resolve conflicts over resources, the females rubbing one another’s clitorises and the males penis-fencing—hardly solutions our leaders would try.

Whereas gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans have clear places in the popular imagination, bonobos are latecomers. Their resemblance to chimps and their home far from the coast, within one of the Congo’s most daunting landscapes, have prolonged our ignorance. Chimpanzees first appeared in Western literature in the sixteenth century, orangutans in the seventeenth, and the gorilla’s name dates back to a Carthaginian who, in 500 BC, traveled Africa’s West Coast and returned with the skins of “wild men” that the locals called gorillae. Though records since the 1880s show apes at the heart of the Congo basin, bonobos were not recognized as a distinct species until the twentieth century. Yale primatologist Robert Yerkes owned a bonobo named Prince Chim in the mid-1920s but thought he was a chimpanzee, albeit an extraordinary one. He wrote: “In all my experience as a student of animal behavior I have never met an animal the equal of Prince Chim in approach to physical perfection, alertness, adaptability, and agreeableness of disposition. . . . Doubtless there are geniuses even among the anthro-poid apes.”

Bonobos were not identified as distinct from chimpanzees until the late 1920s. Harvard zoologist Harold J. Coolidge Jr. wrote that he visited Tervuren, Belgium, in 1928, after a long university expedition to collect gorilla specimens in the Belgian Congo. “I shall never forget, late one afternoon in Tervuren, casually picking up from a storage tray what clearly looked like a juvenile chimp’s skull from south of the Congo and finding, to my amazement, that the epiphyses were totally fused.” This meant that, despite its size, the skull was that of an adult. He found four more similar skulls among those of the chimpanzees and planned to write a scientific paper on the subject, describing a new type of chimpanzee. However, two weeks later, the German anatomist Ernst Schwarz visited, and Henri Schouteden, the director of Tervuren’s Royal Museum for Central Africa, showed him the skulls that had interested Coolidge. “In a flash Schwarz grabbed a pencil and paper, measured one small skull, wrote up a brief description, and named a new pygmy chimpanzee race: Pan satyrus paniscus,” recalled Coolidge. “He asked Schouteden to have his brief account printed without delay in the Revue Zoologique of the Congo Museum. I had been taxonomically scooped.” But reasonably enough, Schwarz had his own account: he’d been studying primates, he wrote, and had come to Tervuren specifically to examine the skulls, a recent shipment from the Congo.

Despite not receiving credit for being the first to identify the bonobo, in 1933 Coolidge published the paper that would establish it not as a subspecies of the chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes, but as a separate species, Pan paniscus. Having remarked the similarities in the torso-to-limb proportions of bonobos and humans, he wrote that the species, still known as the pygmy chimpanzee despite being marginally smaller than most chimpanzees, “may approach more closely to the common ancestor of chimpanzees and man than does any living chimpanzee hitherto discovered and described.”

In 1954, German scientists Eduard Tratz and Heinz Heck proposed that, because of its marked differences from the chimpanzee, the pygmy chimpanzee should be classified under a different genus. They suggested Bonobo paniscus, as they believed bonobo to be the Congolese name for the species. Though the word bonobo wasn’t found historically among the Bantu dialects, it may have been a misspelling on a crate shipped from Bolobo, a town on the Congo River from which bonobos were sent.

While Tratz and Heck’s classification has been generally accepted by the scientific community, some argue that bonobos and chimpanzees are so close to humans that they should be classified in the Homo genus. Even Carl Linnaeus, who in the eighteenth century developed the system of Latin names that botanists and zoologists still use, called the orangutan Homo nocturnus or Homo sylvestris orang-outang, though he based his evaluation on the reports of travelers who claimed that the Indonesian great ape could speak.

Until recently, bonobos lacked public champions whereas the other great apes have had Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Birutė Galdikas. But with a growing number of books, documentaries, and films now dedicated to them, bonobos are becoming media darlings even as they are being exterminated in the Congo. The attention they receive can be attributed to their peaceful disposition and their reputation as Kama Sutra apes—a reputation that is, of course, based on behavior seen through the lens of human sexuality.

The primatologist Frans de Waal writes in Bonobo: The Forgotten Ape of how bonobos use sex for both appeasement and affection, saying that the label sex might be inappropriate if perceived as a “behavioral category aimed at an orgasmic climax.” A little later in his career, though, in response to an article questioning the sexual nature of bonobo behavior, he writes, “Fortunately, a United States court settled this monumental issue in the Paula Jones case against President Bill Clinton. It clarified that the term ‘sex’ includes any deliberate contact with the genitalia, anus, groin, breast, inner thigh, or buttocks.” With bonobos, sex encompasses a number of tendencies—something, de Waal points out, that is also true for humans, though rarely acknowledged: “Our sexual urges are subject to such powerful moral constraints that it may have become hard to recognize how—as Sigmund Freud was the first to point out—they permeate all aspects of social life.” De Waal suggests that bonobo society could teach us much about what human sexuality might look like without those constraints.

As I began to gain a better understanding of bonobos, of what traits they share with humans and how they might experience the world, I encountered the work of Dr. Sue Savage-Rumbaugh, an American primatologist. Since the 1970s, Savage-Rumbaugh has been working with great apes in captivity, investigating whether they have a capacity for language. She first studied chimpanzees at Georgia State University, then bonobos that had been brought from the Congo. She developed technology that enabled bonobos to communicate with humans by pushing a lexigram on a keyboard attached to a computer, which would log and articulate its corresponding word in English. The approach Savage-Rumbaugh developed wasn’t clinical but holistic; she used the lexigrams in conjunction with activities that gave them immediate, relevant, even urgent meaning to the bonobos. But despite her creative approaches, her work remained challenging for years until Kanzi, a baby bonobo who observed the language lessons that his adoptive mother, Matata, suffered through, revealed his skills. On a day when Matata had been taken away for breeding and Kanzi was alone with Savage-Rumbaugh, he began using the keyboard to communicate, producing “120 separate utterances, using 12 different symbols.” She hadn’t realized that he’d been learning English naturally, the way human children do, just by “being exposed to it.”

Kanzi has since become a celebrity, demonstrating his talents on CNN and The Oprah Winfrey Show. Given that a bonobo’s vocal cords are not suited to human language, he has to communicate using his keyboard or a sheet printed with lexigrams. When a lexigram is lacking, he composes, asking for pizza by pointing to “cheese,” “tomato,” and “bread.” He can also understand spoken language and has responded correctly to sentences such as “Could you carry the television outdoors, please?” and “Can you put your shirt in the refrigerator?” even though Savage-Rumbaugh made no gestures and had her face covered. He has also learned to make stone tools, build fires, and cook.

I spoke to Savage-Rumbaugh by Skype not long after she had been selected as one of Time magazine’s one hundred most influential people for a body of work that spans questions of primatology, language acquisition in humans and apes, and cognitive science. I wanted to understand what had won her a place on the list, and I began with the question that I most often heard when I told others about the project I was embarking on.

“Why bonobos? What makes them interesting?”

At first, she answered simply: “In terms of anatomy, genetics, and personality, bonobos are the most humanlike of all apes. . . . They most closely touch the origins of humankind. . . . We still carry so much genetic heritage in common with the bonobo that only by studying them can we have any inkling of what might actually have happened in the past.”

“And this is more true of bonobos than of chimpanzees?” I asked.

“When the data is fully in,” she said, “I think it will be seen that bonobos are more fully related to humans in how their genes express themselves.”

Much of what I had read about bonobos was based on scientists’ field observations, but there’s a line between what we can understand as researchers and what we learn by living with another creature, by sharing in its daily life. Savage-Rumbaugh had worked with bonobos for more than three decades, taking part in their culture while they studied hers, and I asked what this had taught her.

“Freeing oneself absolutely,” she said, “from any thought or tendency toward aggression, and focusing on group love and cohesion—and I don’t mean sex, I mean love—is the way of the bonobos. It’s a message that humanity needs to try to understand.”

“But don’t they have conflict the way we do?” I asked. She acknowledged that they did, often behaving like humans by screaming at each other and showing off their strength.

“But,” she added, “they tend to find ways not to actually harm each other. They search for that. . . . Working with bonobos has given me a perspective on humanity, a perspective on myself that I could never otherwise have had. . . . Jane Goodall changed humanity’s view of itself when she revealed through her efforts with National Geographic that humankind shared a feeling world with chimpanzees. . . . With Kanzi, it has been shown that truly for the first time there are other animals on the planet that can share a language, an intellectual, thinking world with human beings. You put those two together, and you have to ask what is human. So Kanzi is stretching the definition of human. He’s forcing a redefinition of what humanity means. And that for some is intriguing and fascinating. For others, it is very uncomfortable. In part, you can be influential because you upset the social system. Kanzi upsets the social norm.”

If Time had acknowledged the importance of Savage-Rumbaugh’s work, I realized, it was also because of what it says about our dynamic nature: that what we consider human can shift drastically, just as Kanzi is learning across cultures and expanding his notion of self.

“The important aspect of that message,” Savage-Rumbaugh told me, “is that humanity isn’t stuck in the current rut. . . . We might consider ourselves a naked ape, but we have the capacity to be, let’s say, a godlike ape. We can do far more than we’re doing. We have limited ourselves and our understanding of our biology—our understanding of how we must structure the world—by the past. And we don’t have to continue to do that. If Kanzi can learn a language, what can human beings learn? We can certainly learn how to get along.”

I was surprised when I heard the words godlike ape, but Savage-Rumbaugh’s idea wasn’t new; humans often admire and tell stories about those with transformative powers.

“We’re just on the cusp,” she said, “of really understanding how brains interact. . . . We have thought of ourselves as individual sacks of skin. We’re far more connected than we’ve ever understood. And bonobos have almost a sixth sense. They have an understanding of their connectedness. And when we are able to finally grasp and measure that scientifically, I think we’ll be able to know what it means when we say humans have vibes or humans react with each other. I don’t think that’s just a phrase. I think there’s something going on that’s really happening between us, but that linguistically we have, through our culture, shut out. And bonobos haven’t shut that part of themselves out. I want people to realize that we’re just on the cusp of understanding the most fascinating species on the planet—not that elephants and dolphins and others aren’t—but we’re on the cusp of understanding that species and we’re about to decimate it in the Congo.”

In her writings, Savage-Rumbaugh explores the question of bonobo cultures, whether they, like human cultures, exist and are taught, exerting an influence on the instinctive behavior of apes. She describes how bonobos and humans who live together come to share a hybrid culture, an observation that leads naturally to speculation as to how humans might learn a new way of being. Simply looking at the history of human culture reminds us of the degree to which it shapes us, leading us to select for certain genetic traits, the most obvious being the ideas of beauty that we might value at any given time. Culture may become the most significant element of the environment to which we adapt.

I was eager to meet bonobos, to understand what bond they could share with us, how we could interact, and how spending time with them might shift my views. Savage-Rumbaugh was living with bonobos on the outskirts of Des Moines, Iowa, at the Great Ape Trust, a research facility the philanthropist Ted Townsend had created.

It was April when I visited, the sun warm though the air was still cool, the land yet to bloom. A grove of leafless trees and a small lake separate the tall, electrified fence topped with barbed wire from the Trust’s two concrete buildings. Tyler, the laboratory supervisor, a man in his twenties, showed me into the bonobo building and let me watch as he ran experiments with a fourteen-year-old female bonobo, Elykia (“hope” in Lingala, the lingua franca of the western Congo). He told me I’d have to sit in the hallway and stay still, that bonobos were generally shy. He went into a small room next to a glass-walled chamber with a computer touch screen.

A doorway in the back of the chamber opened into the area where the bonobos lived. Elykia entered through it on all fours, craned her neck, scanning the inside, then moved fluidly, rapidly, onto the platform near the touch screen. She gazed out and saw me, her large black eyes opening wide, before she fled in a black blur.

“She’s just being dramatic,” Tyler called to me. “She’ll be flirting with you in no time.”

She neared again, looking in, and made a high-pitched, birdlike sound before bounding to sit on the platform. Though I’d read Japanese primatologist Takayoshi Kano’s description of hearing bonobos in the Congo, like “hornbills twittering in the distance,” I was startled by how different their calls were from the barks and low hoots of the chimpanzees I had seen in zoos.

Elykia glanced around and settled in. Lexigrams appeared on the screen, and she hesitated before touching one with a fingertip. Her hands resembled my own but were long, with more distance between each knuckle. The muscles of her arms were finely shaped, like those of an athlete. She had somewhat less hair than the wild bonobos I had seen in pictures, since captive bonobos can become restless and overgroom. In zoos and sanctuaries, they are sometimes nearly naked, revealing how similar their musculature is to ours, or at least how some of us might like ours to be.

My expectations were high. I’d heard stories of human-bonobo interactions, of bonobos blowing kisses in zoos and staring into people’s eyes. But Elykia forgot about me as she touched the screen, selecting one of several lexigrams, none of which I could understand. Each time, Tyler released a grape through a slot in the wall, near the floor, to reward her. She scooped it with speed and dexterity, barely pausing before refocusing on the screen. I couldn’t imagine a human moving so immediately in response to a stimulus; it was almost as if Elykia’s body were doing the thinking. She touched lexigrams a few more times, and then, hardly looking, she shot her arm out and captured a grape as it began to roll. If we humans have gained brainpower in our evolution, we’ve certainly lost physicality.

After the session with Elykia, Tyler took me through the hallway to the outdoor enclosures, a series of large cages attached by corridors of steel mesh to a yard of yellowed grass. Speaking as he would to a person, he introduced me to an eleven-year-old male, Maisha (“life” in Swahili), who, he explained, was basically a teenager. (Bonobos become sexually mature at nine but do not reach their full adult size until after the age of fifteen.) From watching TV, Tyler explained, Maisha had become obsessed with motorcycles. He didn’t understand why he couldn’t have one. In the same enclosure was Matata, “tough” or “trouble” in Lingala, the group’s wild-born matriarch, now at least forty years old. She rested as Maisha ran back and forth, dragging his laminated sheet of lexigrams across the ground. Seeing me, he threw a paisley cloth over his head and swung along the cage’s ceiling, playing the stooge, then raced out into the sunlit grass.

The differences among the bonobos—the distinctness of their personalities—was undeniable. In the way she held her body, Matata exuded a wild energy, as if her limbs remembered the rainforest. There was authority in her presence even as she dozed, like an old chieftain closing her eyes, barely interested in people like me. She glanced only once before lying on her belly in the sun and going to sleep. Finally, Maisha came over to greet me shyly, lowering his eyes, his fingers hooked in the mesh of the enclosure wall.

Kanzi and his half sister, Panbanisha, whose name meant “cleave together for the purpose of contrast” in Swahili, appeared more curious. As I spoke, I could sense Panbanisha studying me. Her dark eyes peered into my own with a mix of wariness and curiosity that I’d seen on first dates. Female bonobos have pink genital swellings that grow large and pillowlike as they mature, and Panbanisha’s was infected. I asked her how she was, and she stood up and showed me the inflamed area, then sat and crossed her arms, staring at me, as if it might be my turn to reveal something intimate.

As for Kanzi, he was a handsome, well-built bonobo with a wide forehead and barrel chest. He was used to media attention, and when I walked in and he saw my camera, he flashed a photogenic grin and lifted a hand. I failed to snap him in time, and he sighed, appearing exasperated. He studied me, as if to determine just how interesting this encounter might be. After all, he’d played music with Paul McCartney and Peter Gabriel.

Despite their relatively peaceful nature, I wasn’t allowed into the enclosures. Bonobos are significantly stronger than we are, and they can accidentally injure us. There is also confusion around their putative benevolence. The media describe them as sexy, peace-loving creatures, but like us, they can be violent. People are shocked to hear this, since there is a general tendency to simplify, as when we think of someone as “nice” and imagine her, therefore, without anger or jealousy. The same is true of the way we think of bonobos, though by human and chimp standards, they do display remarkable restraint.

My encounters with the bonobos were pleasant, all of them according me some time. They used frequent eye-contact, looking into my eyes as if trying to figure out why I was there. But they didn’t react to me in any dramatic way, except for Elykia, who, as I walked through the building, hooted and peeked from every corner of her enclosure, finally flirting, excited to see a new male.

Kanzi pushed his belly against the mesh and motioned to Tyler, who crouched and tickled him. Kanzi picked up his laminated sheet of lexigrams. Each time he pointed to one, Tyler explained it to me. Kanzi was requesting grape Kool-Aid and celery now, but he was also pointing at lexigrams to indicate that he wanted strawberries before bedtime. Watching, I recalled words from a book Savage-Rumbaugh had co-written with two fellow researchers, Pär Segerdahl and William Fields: “That Kanzi lives in a world permeated with language is visible in his physiognomy. . . . The way his eyes meet your eyes, the way he glances at other persons or cultural objects, the way he gestures towards you or manipulates objects with his hands: everything bears witness to his language.” As Tyler went to the kitchen to get Kool-Aid and celery, I sat on one side of the mesh, Kanzi on the other, a few inches between us. He glanced over and sighed, then just stared off, content with my company on this sleepy afternoon.

Even before my experiences here, my definition of humanity was larger than the one prevalent a few decades ago. Philosopher and anthropologist Raymond Corbey, in his essay “Ambiguous Apes,” describes how, in the 1950s, Belgian cinemas showed a film in which a scientist kills a mother gorilla and skins her body as her infant, soon to be sent to a zoo, sits crying next to her. He writes, “Ten or fifteen years later, such a scene, in a film meant to be seen by Western families with their children, had become unthinkable.” He reflects on French philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas’s theory that the gaze of another “appeals directly, without mediation, to our moral awareness,” and he asks whether this holds true when it is not the gaze of “a human child but that of a gorilla child or an orang-utan child?” However, human attitudes are changing, and if we were exposed to the suffering of hunted and imprisoned great apes rather than to glossy photos of wildlife beauty on NGO fund-raising calendars—and if we understood the causes, frequency, and severity of this suffering—we might respond in greater numbers.

A firsthand experience, of course, has a different level of power, and for me, even during my short visit to the Great Ape Trust, there was no doubting the intelligence in the gazes of the bonobos. When we look into another’s eyes, we can tell whether her mind is spacious, holding room to consider, to see things from different angles and evaluate them, or whether she is simply carrying through motions, confined, driven by instinct and habit.

How would the bonobos in the Congo appear to me? Kanzi and Panbanisha were used to humans, my own visit insignificant to them. They’d taken a step into our world despite the gap between us, a gap made clear by the steel mesh of the enclosures—one no doubt smaller for those who worked with them. Though I was curious to know how I would perceive bonobos in the abundant rainforest that had formed their bodies, instincts, and cultures, I also wanted to see how conservation efforts could protect them. I was only beginning to understand that bonobos lived in social groups not so different from those of humans, sharing many behavioral traits with us: playing games, daydreaming, teaching children, establishing friendships, caring for each other’s injuries, or grieving for the loss of loved ones. It was hard to imagine their families broken apart, the adults shot, their bodies butchered or smoked, sold in bushmeat markets; the traumatized infants tied in baskets, starving for weeks as traders attempted to sell them. This, too, was part of the story, and I wondered if, when I saw the bonobos in the rainforest, it would affect the way they looked at me.