Читать книгу Of Bonobos and Men - Deni Ellis Bechard - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеKinshasa

For many Westerners, it would be hard to travel to the Congo without confronting the way our cultural narrative portrays it: through a media rap sheet of barbarism so long it predates Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. But what our fear blinds us to is that these descriptions say less about how the Congolese traditionally lived, and still live, than about the result of their living in one of the most fertile, mineral-rich, and strategically important nations on earth.

Before Western colonization, the area that now constitutes the DRC was home to dozens of complex societies. Over four hundred years ago, the Kongo Kingdom had ambassadors in Portugal, Spain, and the papal courts, as well as organized and trained militaries. The slow rise of the Portuguese slave trade—in conjunction with the spread of cash crop plantations in the New World—eroded the kingdom. In the late nineteenth century, rather than export the Congolese, the Belgians enslaved them at home, further disintegrating the social fabric. From there, the story of the Congo is one of constant exploitation: of humans, rubber, ivory, lumber, cotton, coffee, copper, cobalt, gold, diamonds, and now coltan, used in computers and handheld electronics. Since the colonial period and all through the Cold War, the West has fed the country a steady flow of weapons and bought its raw materials, whether from the regime of Sese Seko Mobutu, its president from 1965 to 1997, or from Belgium, Uganda, and Rwanda, usually to the detriment of the Congo’s people. Even the recent wars have had less to do with the Congolese than with the outside world, with Western industrial and military interests, rivalries between developed nations, and the increased global demand for minerals. And yet, though the ambitions and material needs of other nations have charted the Congo’s decline, we often misread Heart of Darkness, telling ourselves that the darkness is in the Africans.

Being familiar with the West’s fears, I tried to consider the situation from the African point of view and realized that the obvious question was, what are the Congolese afraid of? One answer—being exploited and manipulated by outsiders—makes clear the challenges of large-scale conservation here. Building trust is no easy task. Africa’s most brutal colonial history and its most corrupt Cold War–era dictator have left the Congolese both wary and desperate. After the United States ceased to prop up Mobutu and he lost power in 1997, war killed as many as five and a half million people, the majority from disease and starvation. Soldiers, whether those of the Congo’s government or the numerous rebel forces, pillaged and raped, often as a means of controlling local populations, and spread HIV into even the most remote areas. Villagers abandoned their fields and hid in forests to protect their families, hunting for survival and decimating the wildlife. By 2011, the DRC received the lowest rating on the UN Development Programme’s Human Development Report, which tracks progress in health, education, and basic living standards.

For conservationists to work successfully here, they have to understand the people well enough to build trust and at the same time harness their desire for change. In our conversations, Sally Jewell Coxe of the Bonobo Conservation Initiative distinguished between two basic conservation approaches: one that the Congolese often see as colonial in attitude, whereby outsiders come with money and impose change, and the other whereby outsiders integrate with local communities, respecting their values and supporting their leaders in order to achieve shared goals. However, conservation often requires a quid pro quo: the local people taking the pressure off the forests and wildlife in exchange for new means of survival. Conservationists can foster trade, health care, education, even law enforcement, and yet if they want to build a deeper sense of community investment, they need insight not just into the problems that arise but into how those problems came to be. Part of finding a new way of relating to people, Sally suggested, lies in seeing how much damage was caused by the old way.

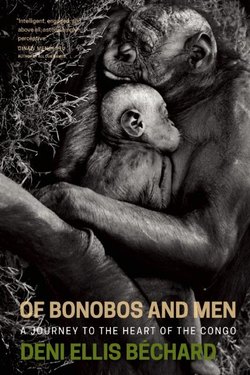

In telling me about BCI’s projects, she spoke of the Bongandu, the Congolese ethnic group with whom she’d worked primarily. She described their respect for bonobos and their knowledge of the rainforest, emphasizing that we must not equate poverty with ignorance. As for bonobos, they served as a flagship species, a concept that elevates the profile of one animal to protect the biodiversity of its habitat. The bonobos’ charismatic nature made it possible for BCI to rally support around them as a symbol of the rainforest.

Through 2010, I researched rainforest and bonobo conservation, and on several occasions, I interviewed Sally by Skype. I listened carefully, trying to determine if BCI’s projects could create lasting change, and what could be learned from the solutions they were finding. In mid-2011, I proposed accompanying them on an expedition to a bonobo reserve. I wanted to understand how their model differed from those of other NGOs, and how building coalitions and social capital could make up for a lack of funds. Sally told me that such a trip could be a stunning experience, but she also emphasized that the reserve was set up with only the bare minimum, for the purpose of work. And she warned me to budget well. Just getting to Kinshasa would be expensive since so few airlines served it. Then we would have in-country flights, and because there was little infrastructure for trade, food and supplies would be costly.

BCI had been going through a difficult period, struggling to fund its operating costs. The continuing aftershocks of the global financial crisis had diminished the flow of charitable donations. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq exhausted the US economy and political will, and with the Arab Spring, then the tsunami and nuclear meltdown in Japan, the media’s attention wasn’t on conservation. Not until late 2011 did BCI have the funds for its next expedition into the rainforest.

But in November, the DRC held its second free multi-party elections since not only the end of the Second Congo War in 2003 but the country’s independence in 1960. The Congolese were dissatisfied with their current leaders, and the media anticipated violence and conflict over ballot rigging by each candidate’s supporters. Given that we would be as far off the grid as possible, we needed to be careful not to get caught in the rainforests if conflicts reignited. BCI’s contacts in the reserves said that the atmosphere was tense, with local politicians looking for ways to leverage power, and they warned us to postpone the trip.

I was already overseas, and I flew by way of Doha, Qatar, to East Africa. I took my time in Uganda and Rwanda, learning about conservation efforts there. Election results were announced in December, and Joseph Kabila, the incumbent president since January 2001, was reelected to a second term despite allegations of fraud. Though the DRC’s security forces killed at least two dozen protesters, and residents of the capital stoned a Westerner’s car, blaming the election results on foreign intervention, the peace held. The Congolese, it seemed, were sick of war.

Finally, on February 3, 2012, the day after my arrival in Goma, and after two trips to the offices of the Compagnie Africaine d’Aviation (CAA) to make sure my flight to Kinshasa would be departing, I took a taxi to the airport. One side of it was heaped with broken chunks of volcanic rock, and a few junked planes had been shoved off the runway, brown with dust, their noses to the sky.

Beyond security, a man at a desk again recorded the details of my passport. I noticed a single bullet hole in the top of the window behind him. He interrogated me on my reason for being in the Congo just as another agent would do when I arrived in Kinshasa, as if the sky above the DRC were a different country and each return to earth required a new visit to customs.

The plane was on time, and as it took off, I stared out the window: a military helicopter parked in the distance, khaki cargo planes, a cannon and a tank, both draped with dun tarp, set back in the trees. A narrow neighborhood of clustered homes with tin roofs passed beneath us, then the city of Goma with its wide avenues and desolate roundabouts, and the shore of Lake Kivu, the dark volcanoes of the Virungas to the east. Soon we were above hills, the unbroken thatch of the forest, before we lifted through a bank of clouds.

For a while, we glided just above them, working our way into a dense, otherworldly terrain. Dozens of cumulonimbus rose above the white plain, casting long clefts of shadow over it. All across the glowing horizon, at the luminous blue line between the clouds and the sky, further cumulonimbus soared, red at their edges, flattened by the cold air above, like mesas in a primeval vision of the American Southwest.

Though I fly often, I’ve never tired of cloudscapes, and I’d never seen one like this. It seemed an expression of the Congo basin, 695,000 square miles, approximately 20 percent of the planet’s remaining tropical forest, spanning Gabon, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo as well as its similarly named neighbor, the Republic of Congo. We were crossing over its edge, thousands of feet down, heat and humidity boiling up as it breathed dense air into the atmosphere.

It’s hard to imagine forests like this vanishing, though farmland and plantations have replaced them in most of the world. What makes the impact of deforestation difficult to grasp is that it’s at once gradual and rapid. Humans have cut down much of the world’s forests, including the vast majority of old growth, and we can no longer fully comprehend how they influenced regional climates, regulating humidity, preventing drought, and protecting rivers, watersheds more likely to dry up if exposed to the sun. The vast quantity of carbon released from felled and burned trees escalates climate change and is absorbed into the oceans, gradually acidifying them.

Even now, massive swaths of forests are vanishing. In Southeast Asia, where the human population is booming, forests are being decimated for palm oil plantations, diminishing the orangutan habitat by 50 percent each decade. In Brazil, forests are being cleared for logging, cattle grazing, and soy. In the Congo, with the new political stability, logging companies are again seeking concessions. At a time when industrial powers are charting this forest’s worth, a conservation plan for it is urgent.

For more than an hour, the plane flew above the clouds, larger cumulonimbus muscling up, the sun flaring at their edges, falling quickly now, a blinding disk edging against the white landscape. And then we passed beyond the clouds, into a clear sky, and in the twilight, we swooped low over Kinshasa, the nation’s capital, the rolling savannah beyond it scattered with homesteads, before landing at N’Djili Airport.

Over the years, the articles and books I’d read about the DRC described aggressive people—pushing, shouting, asking for bribes, travelers shoving each other in airport lines. This wasn’t my impression, neither here nor at the border crossing. People apologized for bumping into me, and even the security agents, notorious for extortion and made-up taxes, were courteous, one telling me he was a poet, adjusting his glasses as he explained that he wrote about AIDS, inequality, and handicapped children. Maybe the DRC was changing. Life here certainly used to be worse. But I’d traveled enough not to fixate on media reports, which rated Kinshasa as one of the most dangerous cities in Africa and described the Congo with a daily fare of spectacularly depressing statistics and stories of inhumanity—massacres, slavery, mass rapes, cannibalism, and brutal witchcraft. These reports, though necessary and true in certain regions, easily blind outsiders to the great majority of the country’s people, who work hard to feed themselves and their families.

Eric Epheni Kandolo, a Congolese conservationist in his late twenties and BCI’s communications coordinator, was waiting for me at the airport. Short and solidly built, he spoke as if we’d known each other for years. This immediate familiarity, I was soon to learn, is one of the most endearing qualities of the Congolese. Eric explained that his taxi had refused to wait, and he asked if I’d like a beer while he found another. I declined, but he led me to a beer stall anyway and said I should wait there since he needed to negotiate with taxi drivers.

“If they see a white man,” he told me, “the price won’t be very good.”

He found one, a car of no discernible make, its windshield webbed as if hit by a brick, every panel a different color. When I opened the rear passenger door, the smell of the dark, musty, tattered interior cast me decades back to the rural Virgina junkyards I prospected in as a teenager, looking for parts to rebuild my car and motorcycle.

Beyond the airport, men gathered around booths selling Vodacom, Tigo, and Airtel phone cards, talking and laughing, money changing hands. In the shade of a concrete building, a teenage boy lounged on a swatch cut from a car rug next to a stack of used tires for sale. Women carried bundled market goods on their heads, their spines drawn long, necks as elegant as those of ballerinas.

We drove into the most densely populated neighborhoods of Kinshasa, the wide, uneven streets of broken asphalt littered with trash and rubble and crammed with vehicles. Many of these were also patched together, their varied panels so dented they appeared as if they’d been beaten into place with hammers. People ran through traffic that didn’t slow or swerve. Huge unbranded trucks rumbled past, looking as if assembled from dozens of old vehicles, their engines half exposed. At least one hundred yellow jerry cans were tied to their sides and the cargo was lashed down beneath blue tarps, young men sitting on top.

Eric launched into a political discussion with the taxi driver, a rail-thin man with a weathered, angular head and veins so prominent that his forearms appeared twined with electrical wire. In excellent, mildly academic French, the driver debated President Kabila’s merits, pointing out that though he wasn’t popular in Kinshasa, he was gaining support. As he and Eric broached the topic of whether the president was promoting the country’s development while protecting its national resources, a red passenger van with a rectangular opening in its side cut into our path. Our driver braked and swerved, and Eric told me that these vans, group taxis, were called les esprits des morts, “the spirits of the dead.” They were the most salvaged-looking vehicles on the road, their headlights and grilles missing, people crammed into them, a few clutching the edges of the doorless openings.

Suddenly, our taxi hit a border of raised asphalt and we were in a different city, one of smooth, dark, wide avenues with fresh white crosswalks painted on them, symmetric lines of streetlamps, an immense lit-up hospital off to the left. Eric told me that it was the largest hospital in Central Africa, that all of this, the perfect boulevard and the hospital, was the work of the Chinese, who were opening mines and building highways into the continent’s interior. The vehicles, though, remained dented, and the red or yellow vans, les esprits des morts, raced ahead, the eyes of their passengers shining through the open sides.

We finally stopped at a drab concrete building that looked uninhabited. It stood at a curve in the busy two-lane street where vendors sold grilled meat on sticks and men and women lined up to hail any car with an empty seat. But just past the metal gate, a flight of stairs climbed to BCI’s offices. When I followed Eric inside, I expected to see the small operation they were when I began researching their work several years ago. At that time, BCI consisted of two or three people in the US and a few in the Congo. Now, I saw five Congolese, two women and three men, sitting at desks, working at computers. They introduced themselves: Evelyn Samu, BCI’s national director; Dieudonné Mushagalusa, deputy national director; Richard Demondana, finance manager; Dominique Sakoy, accounting assistant; and Corinne Okitakula, legal officer. Two others, Bienvenu Mupenda, chief of operations, and Papy “Pitchen” Kapuya, program assistant and logistician, had flown to Équateur’s capital, Mbandaka, a city 365 miles up the Congo River, to join BCI staff stationed there, and would soon be on boats, taking supplies upriver to the Kokolopori Bonobo Reserve.

Michael Hurley, BCI’s executive director, left his computer and shook my hand. He pushed his glasses down to speak, pale indentations on the bridge of his nose where the skin had been damaged after many years in the sun. He was maybe six feet tall, with wavy gray-blond hair, and though fifty-nine, he had a boyish smile, his front teeth slightly overlapped.

“This week has been overwhelming,” he told me. “Sally rushed here from DC for a meeting with the national government. Now we have deadlines with the African Development Bank, and we are working to meet their criteria.”

Standing at a map, Michael pointed out fifteen conservation areas under development within the bonobo habitat, 193,000 square miles of dense forest to the south of the Congo River. BCI’s goal, he explained, was to create a chain of protected areas that, linked by wildlife corridors, would become the Bonobo Peace Forest. Over a period of ten years, during which their annual budget had grown from about $100,000 to a million dollars, BCI had helped establish three times as much government-recognized protected area as all of the big NGOs in the DRC combined: the Kokolopori Bonobo Reserve (larger than Rhode Island at 1,847 square miles) and the immense Sankuru Nature Reserve (11,803 square miles, bigger than Massachusetts). A number of other reserves were under development and would eventually link up to Kokolopori and Sankuru, protecting a huge swath of the bonobo habitat.

Michael put his index finger on the area we would be visiting: the Kokolopori Bonobo Reserve at the upper reaches of the Maringa River, a tributary that flows northwest before curving south within the Congo’s great riverine arc. The dark green of the Congo basin covers much of Central Africa, its many tributaries trending west as the Congo River flows north and then turns toward the Atlantic Ocean before veering south, picking up the tributaries and growing in size. I gradually charted our path within this labyrinth that, more than anything else, mapped out the uniform expanse of the rainforest.

From the office down the hall, Sally Jewell Coxe, whose voice I recognized from our numerous telephone conversations, called out a question I missed because part of it sounded like Lingala, or maybe someone’s name. Michael crossed the room, shouting out information for a report she was about to deliver. He realized he left his coffee mug on his desk and, still talking, reached back for it even as he seemed to be moving forward.

Sally was fifty-one, eight years younger than Michael, with sandy hair and large green eyes that gave an impression of someone who loved observing the world. Like Michael, she got lost in her train of thought, and over the next few days I would see her checking budgets, writing grant applications, and contacting donors while fielding calls from Mbandaka to prepare the boats that would take supplies on the ten-day trip to the reserve, then following up with staff to make sure those supplies were ready: hand pumps and ultraviolet SteriPENs for drinking water; medicine for the reserve’s clinic and for BCI’s staff in case anyone got malaria; headlamps, machetes, and new rain ponchos for trackers and eco-guards; batteries for everything and everyone. The list went on.

Another concern was transporting fuel to the reserve. Because of its high price in the DRC, the fuel for the outboard motors and for a month in the reserve, where it would be needed to power generators, motocycles, as well as a Land Cruiser and a Land Rover, could cost $10,000. This was still cheaper than paying to take all cargo and passengers by bush plane, or buying fuel there, where it was marked up three times. The boats could bring more supplies and more people, but the time the trip would take depended on the water level. We were at the end of the dry season, when the boats often got caught on sandbars and had to stop at night.

As Sally spoke, I could barely keep up with all of the details. Skype beeped constantly on her computer, receiving messages from BCI’s office in Washington, DC.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I just have to send a report. I’ll be right back.”

Both Sally and Michael worked the nine-to-five shift in two time zones, until the US office closed at 10:00 p.m. West Central Africa time, and when I said goodnight, they hurried back to their computers in different rooms, still calling out to each other. They had been a couple for ten years, BCI in its early stages when they met. Its current incarnation was in many ways the fruit of their relationship.

That evening, I stayed at the home of BCI’s national director in the DRC, Evelyn Samu, a statuesque woman with a still, appraising gaze and a sudden, at times wary smile. She’d been in conservation for over fifteen years and lived with her younger brothers, her granddaughter, and her niece. Her father had been a successful businessman under Mobutu and built the sprawling home off Matadi Road. Its pipes were a less reliable source of water than the swimming pool where insects skimmed the surface, so the maids filled blue plastic buckets and carried them on their heads to the tiled bathrooms. When the power failed, they switched to another network, from a different hydroelectric plant, and when both grids went down, they waited until nightfall to start the generator. Well-kept gardens surrounded the grounds, and the terrace by the kitchen offered a view of the western horizon, its rolling blue hills speckled with buildings, the setting sun spectacular over the savannah.

The night was pleasantly warm. Normally, in the DRC, the dry season south of the equator lasts from April to October, the opposite of the seasons to the north of it. There is little variation in temperature, with a yearly average high of 86 degrees Fahrenheit and an average low of 70. Kinshasa usually has a particularly short dry season, from June through August, but there had been almost no rain that February, and the dust and the lingering, acrid smell of smoke from trash fires had the Congolese wondering when it would rain.

The next morning, before departing for the BCI offices with Evelyn, I waited at the front gate of her home as she prayed near a wall-size shrine to the Virgin Mary. Michael had told me how much energy it took to get around and shop for basic needs, how demanding life was for BCI’s staff. Just traveling the four miles to BCI’s offices gave me a sense of the city’s pace, at once hectic and painfully slow. People rushed cars with an empty seat or trucks with space in the bed even as traffic stopped for minutes at a time. Vehicles crammed the street as far as I could see, the distance obscured in the smoke of burning roadside trash.

The only clear geographic marker for Kinshasa is a widening of the Congo River called the Pool Malebo, formerly Stanley Pool. On the map, it nearly resembled a bull’s-eye, an immense lake partially filled in with an island of sediment, around which the river flows. It separates the world’s two closest capitals, that of the DRC from Brazzavilla in the Republic of the Congo, a former French colony.

Kinshasa, founded in 1881 by the American explorer Henry Morton Stanley and named Léopoldville after the Belgian King, served as a trading post where the river’s navigable stretch ends. One of the challenges of colonization was that the river, though providing a route into the continent, began its descent to the ocean, just beyond the Pool Malebo, by rocketing down dozens of narrow cataracts. To link Léopoldville to the port, a railroad had to be built across Bas-Congo Province, a panhandle that attaches the country’s massive inland territory to its scant twenty-five-mile stretch of Atlantic coast.

During the colonial era, Kinshasa’s nickname was Kin la Belle, “the beautiful.” Now it’s referred to as Kin la Poubelle, “the trashcan.” Heightening the sense of disorder is the construction underway in many parts of the city, fueled by the postwar rush for minerals. During the recent wars, the borders the DRC shares with nine other countries were often less boundaries than sieves through which its wealth escaped. Now, with the growth of industry in India, China, Brazil, and Russia causing an increased demand for raw materials, the minerals are often still sold illegally through the DRC’s neighbors, notably Rwanda. The Chinese are renovating the capital and building highways into the Congo’s interior in exchange for mining contracts, and the country’s elite are profiting. Signs of commerce are everywhere, with new buildings going up helter-skelter even as those next door are collapsing.

The effect of all this was overwhelmingly claustrophobic, with a seventh of the country’s seventy million here, many from the provinces for work or in refuge from ethnic conflict. One in five adults is HIV positive, and, unable to afford health care, the vast majority resort to faith healing and magic. In Planet of Slums, Mike Davis suggests that among the world’s megacities, only the poverty of Dhaka, Bangladesh, compares to that of Kinshasa, where less than 5 percent of the population earn salaries, and the average yearly income is less than one hundred dollars. All along the street, young men in torn, colorless clothes sold goods or looked for work. They crowded into the road, trying to find rides. Six or seven at a time stood on a single rear bumper. They held onto tailgates or the back doors of vans, fingers hooked at the edges; at stops, they lowered a hand and shook it out, repeatedly extending it back to a familiar shape.

Group taxis crammed passengers in, many of them hugging baskets or synthetic gunnysacks. On my second day, I traveled without Evelyn, and it took me longer to get a ride. The Congolese barely had to gesture; they just leaned forward, revealing what they wanted with their gazes and postures. As I’d been taught, I lifted my arm and pointed my thumb or index finger to indicate the direction I would take at the next fork in the road.

Though I’d been told that the Kinois, the residents of Kinshasa, would work me over for every penny, on my first two rides, the drivers wouldn’t let me pay. One steered a rumbling Mercedes, its windshield split, its sunbaked paint cracked like pottery glaze. Passing a crowd, he swerved to the roadside and handed me a brick of dirty Congolese francs nearly the size of a cinder block, asking me to give it to a stooped old man in a brown button-down shirt who hurried over to meet us. Maybe the driver didn’t need money, I considered when he dropped me off, refusing my cash, telling me that he enjoyed the conversation.

Each time I visited the offices, Sally and Michael were finishing grant applications and ironing out plans for our trip. The staff rushed about, coming and going, making lists and compiling reports, their cell phones chiming and ringing, Skype beeping in the background.

As I spoke to Michael, he paused to rub his eyes and catch his breath, and I realized that what I’d been taking for exuberance may have also been the jitteriness of exhaustion.

“We’ve gone from being a small NGO to something a lot bigger overnight,” he told me. “We’ve hired new office staff in the US, and we had to delay our arrival here so we could train them. And we’ve expanded our staff here as well. We have grants for work in the field, but not enough of that goes to operating costs, so we’re struggling to maintain our offices.”

That evening, some of the BCI Kinshasa staff left quickly, careful not to go home too late, when gangs armed with machetes came out. Known as kulunas, a word from Angola, from the Portuguese coluna, “column” (used for soldiers on patrol), the thugs prowled outlying neighborhoods, their faces at times painted like skulls. There were so many daily challenges for the staff and so many varied discussions in the offices—of landing strips in the rainforest, grant proposals for new vehicles, rural clinics running out of medicine, celebrities contacting BCI in hopes of seeing bonobos in the wild.

Sally joined the discussion, coming in from the next room to tell me that BCI was experiencing a sea change, a make-it-or-break-it moment. She worried about money, and in my short time there, I’d noticed that everyone in the Congo seemed to be asking for it, calling the offices and demanding it. Each time this happened, she explained deliberately to the caller what BCI could and couldn’t do, when certain funding would arrive, that she and Michael were working on new budgets, more grants, and to be patient. She told me that BCI was barely managing to fund the people on the reserves, that she and Michael almost never paid themselves, and when they did, they ended up putting the money to an emergency somewhere in the field.

Over the next week, the BCI team decided to push back our flight to Mbandaka once, then again. Normally, they ran their trips separately, one staying in Kinshasa or DC while the other was in the field, living in mud huts for months at a time to support their Congolese partners as they established or oversaw programs. But they hadn’t been to Kokolopori in over six months and had a lot to do. They chartered a bush plane from Mbandaka into the rainforest with Aviation sans Frontières and sent the boats loaded with supplies to meet us at the reserve. Two of the Kinshasa staff, Bienvenu and Pitchen, were on board, as well as BCI’s boatmen who were based in Mbandaka. After a month in Kokolopori, we would all return together to Mbandaka by boat.

Two days before we were to leave, and three after the boats’ departure, Sally got a phone call: two outboard engines had died and the boatmen couldn’t find parts in Basankusu, a town on the Lulonga River at the confluence of the Maringa and Lopori, a day or two from the Congo. Eric, who had just arrived at the offices freshly shaved, a blue oxford shirt tucked into his jeans, set out to find replacement parts and put them on an upcoming flight to Basankusu. All day the Kinshasa staff bustled about, Dieudonné getting our photography permits since it is illegal to take photographs in the DRC without governmental permission.

We delayed once more, Sally and Michael repeatedly working until after midnight. Then, a week and a half after my arrival, we were ready. We loaded the bed of a white pickup with large yellow duffel bags printed with the letters BCI and drove back toward the airport as I stared out the truck window, taking in the city’s turmoil. Women paused between four lanes of rushing traffic, plastic tubs the size of laundry baskets on their heads. Shirtless men broke old concrete with sledges, piling chunks on the median, each muscle in their torsos knife-thin and close to the skin. Further on, boys played soccer in an empty lot among the scorched hulks of old trucks and heaps of smoldering trash. There were merchants in sooty storefronts, peddlers by loaded handcarts, students waiting for buses, office workers, men and women in pressed suits and skirts, climbing into taxis with mismatched panels, holes drilled along their edges, wires knitting them together.