Читать книгу Of Bonobos and Men - Deni Ellis Bechard - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue: February 2012

On a sweltering afternoon, I reached the border that separates Gisenyi, Rwanda, from the city of Goma in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The sky was cloudless, the sun glaring on the dusty, broken roadway and the windless lake that stretched alongside it. After receiving the Rwandan exit stamp in my passport, I walked around a metal gate raised by a single soldier for passing cars, though there were none.

I approached the yellow building on the other side, where an agent sat at a counter, behind an open window. He suddenly appeared engrossed in organizing his desk. He thrust his jaw and furrowed his brow, gathered papers into a pile, then spread them like a stack of cards. He scanned the pages, moving his head back and forth, as if hunting the source of a grave injustice. I’d often seen officials do this, demonstrating self-importance, making travelers wait, creating an atmosphere of disapproval and difficulty, so that when they finally took the passport, it would seem natural for them to find fault and demand an additional payment.

Across the street from the yellow building, in what appeared to be a small guardhouse, a door opened, and another agent stepped out, perspiration beading on his round face. He hurried over, smiled at me, and reached for my passport. The first one grunted and shook his head, sat back in his chair and crossed his arms, staring off in anger.

The new agent stepped into the yellow building, behind the counter, and flipped open a book of smudged graph paper. He wrote my passport information, asking my profession and, when I said écrivain, “writer,” what I would be writing.

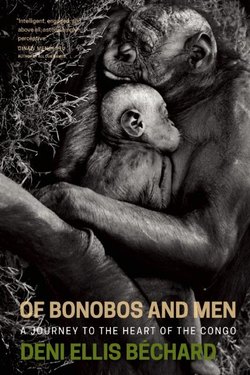

“A book on conservation,” I replied in French, “on tropical forests and natural resources, and endangered great apes.” He listened, his eyebrows raised, nodding as if I were corroborating a view he had long held. Seeing his look of genuine interest, I offered more details: my planned visit to a community-based reserve in the Congo’s Équateur Province, the importance of conservation not only for the wildlife, but also for the local people.

I showed him my letter of invitation, and he studied it, the page explaining that I would help “protect biodiversity by writing a book about the Bonobo Peace Forest . . . and raise up the image of the DRC in its conservation efforts.” When I’d received it a month before, the ambitious statements surprised me. The letter was necessary for my visa, and I was beginning to understand that the Congolese who composed it must have thought it important to impress officials. Now, as this one read it, he nodded repeatedly. When he finished, he flashed me a broad smile and thanked me, with what sounded like earnestness, for having come to the Congo. He stamped my passport and said, “Bon voyage.”

As I walked, jumbled concrete buildings and a few sprawling hotels cluttered the descending land between the road and the rocky shore of Lake Kivu, its waters reaching to a hazy blue line at the horizon. Five young men on motorcycles shadowed me, asking if I wanted a ride, though I could easily reach the hotels on foot. Where the road branched inland, the city appeared empty, a ghost town but for two white UN Land Cruisers racing in the distance, lifting plumes of dust.

It was hard not to be vigilant. From my readings, I had mixed impressions of Goma, a backpackers’ haven that, in the almost two decades since the Rwandan genocide, had become the epicenter of a chronic warzone. To make matters worse, in 2002, about 40 percent of the city, then home to more than half a million people, was destroyed in the eruption of Mount Nyiragongo. A stream of lava at times two thirds of a mile wide had poured through. Even now, volcanic rock protruded from the dirt where the roads were unpaved, catching at the wheels of passing motorcycles.

I was most struck by how the Congolese looked at me. Rwandans and Ugandans were used to visitors, and even those who wanted to sell something gave no more than cursory attention, whereas the Congolese I passed studied me, as if to see who was before them, to know why I was there. They carried more scars, on foreheads and cheeks, or had missing teeth, a droop in the corner of an eyelid, hints of old injuries in the way they walked, positioned themselves to pick up a bag, or rode a motorcycle. They gazed at my eyes, narrowing their own, at once cautious and curious. But when I smiled, they smiled back quickly, as if relieved.

I spent that night in the only hotel I could find with a vacancy, the others filled with the personnel of NGOs. My room was more luxurious than I expected, with polished wood cabinets and shiny bathroom fixtures, though nothing quite worked. Electric sockets sizzled when I wiggled the plug, but gave no power; the shower head dripped, and none of the doors, bathroom or wardrobe, sat well on its hinges.

I was too tired to care, but after I lay in bed, I couldn’t fall asleep. The next day, I’d fly to Kinshasa, one of Africa’s most populous and chaotic cities. If all went to plan, a week later I would head into the forest, either by dugout canoe or bush plane. I’d looked at maps, at satellite images of the Congo basin rainforest, the second largest on earth after the Amazon, its hundreds of rivers the real highways, far more perceptible than the occasional yellow line of a dirt road. How would it feel when the only clear space was that surrounding a few huts, each village an island of sky? If you walked out, you traveled for weeks beneath the trees, barely seeing the sun.

But to experience this place and its people clearly would require a conscious decision to look beyond the stereotypes. The Western view of the Congo remained limited by colonial mythologies: the great river, the dark heart of Africa, notions that Cold War rivalries, mineral exploitation, and the recent wars had kept alive in our minds. The Congo had come to signify savagery, and hearing its name, many shuddered without quite knowing why. But for millions of Congolese who struggled to build ordinary lives, this shudder pushed them deeper into alienation, further from the global community. The shudder increased our blindness not only to the forest and its importance to life on earth, but to the very people whose actions were crucial to saving it.

Outside my window, Goma was silent but for the occasional passing vehicle and the brief, muted voice of the guard in the hotel’s entrance.