Читать книгу Of Bonobos and Men - Deni Ellis Bechard - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

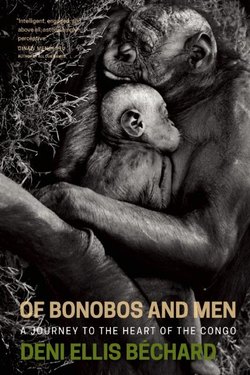

ОглавлениеThe Bonobos of Kokolopori

If bonobo research and conservation have taken a firm hold in this part of Équateur, it is because of the Bongandu, one of several tribes that inhabit Équateur Province. Japanese primatologist Takayoshi Kano explored the region in 1973 by boat, truck, and raft, and by crossing hundreds of miles on bicycle, all the while asking villagers where the bonobos lived. He found that few remained in the west of their habitat, where they were hunted. But when he crossed east of the Luo River, where Kokolopori is located, he entered the territory of the Bongandu, and learned that there were numerous groups of bonobos lived in the forests.

Bongandu literally means people of the Ngandu culture (“bo” signifying “people,” and “mo,” as in Mongandu, referring to a single individual of the ethnic group). The Bongandu believed that bonobos walked on four legs only when watched, but otherwise went about like humans. Unlike the Congolese in neighboring areas, they saw bonobos as distant ancestors and had a taboo against hunting them. Consequently, there were large numbers of bonobos, and they were relatively unafraid of people. Kano established his first research camp in an area that, nearly two decades later, would become the Luo Scientific Reserve, not far from where the Kokolopori Bonobo Reserve has since been established.

The work done at Kano’s research camp from the 1970s on set the foundation for our current understanding of bonobos, how they bond socially and sexually. Essential to their nonviolence, the Japanese researchers realized, is the stability of their groups. Since chimpanzees have to forage over great distances and expend significant energy to find limited food supplies that are patchily distributed, they travel in small groups to prevent competition among their own members. However, the bonobos have more varied diets and can remain in larger, more stable social groups that allow females to bond. Such coalitions, which tend not to exist in the chimpanzee world, permit female bonobos to limit the aggression of males and even prevent some from mating. Recent studies theorize that bonobos may have essentially domesticated themselves, females selecting those males best for group cohesion and thus gradually eliminating aggressive traits from the gene pool. Not only are the statuses of males determined by those of their mothers, but they will always side with their mothers during conflicts. And, even if the highest-ranking bonobo male attacks a female, all of the females will gang up on him and defeat him.

One of the mysteries of these coalitions, however, is why females forge such strong bonds when, as adolescents, they leave their family groups and travel to new ones to prevent inbreeding. How can unrelated females not find themselves competing for resources and male attention? The research of Takayoshi Kano and Gen’ichi Idani offers an explanation. When adolescent females come upon a new community, they each select an adult female in that group. Each one lingers nearby, observing the older female, attentive to her needs, and if the older female is welcoming, the adolescent approaches to groom, sit close together, or have sex. Though scientists have labeled the latter genito-genital rubbing, or GG-rubbing, Dale Peterson and Richard Wrangham write that this term “hardly captures the abandonment and excitement exhibited by two females practicing it.” They suggest using the Bongandu’s expression for it: hoka-hoka. The older female reclines and opens her legs, and the adolescent climbs on top. Wrangham and Peterson describe the act as resembling humans in the missionary position.

Their hip movements are fast and side to side, and they bring their most sensitive sexual organs—their clitorises—together. Bonobo clitorises appear large (compared to those of humans or any of the other apes) and are shifted ventrally compared to chimpanzees. Kano believes their location and shape have evolved to allow pleasurable hoka-hoka—which typically ends with mutual screams, clutching limbs, muscular contractions, and a tense, still moment. It looks like orgasm.

Though sex among the females establishes a bond that likely strengthens the overall female coalition of the group, there are other factors that prevent male aggression. For instance, chimpanzee females emit an odor when ovulating, causing males to go into a frenzy and compete to breed with them, whereas female bonobos neither show clear signs of ovulation nor limit sexual behavior to their fertile period. The result is that males have no notion of individual paternity, and all males are caring and nurturing with infants. This strengthens the bond between males and females, and reduces the competition among males, supporting a social order that, compared with that of chimpanzees, is highly stable, based as it is around dominant females who maintain power until their deaths.

On our first trip to see the bonobos, we got up at 4:00 a.m., ate and dressed rapidly, then went out into the dark, to BCI’s Land Rover this time. Michael had brought a new axle for it, but the reserve’s mechanic had mistakenly asked for a rear one. Michael and Jean-Pierre had returned in the Land Cruiser to Djolu and had the broken axle welded. They’d also picked up Alan Root, who’d arrived by bush plane. One of the most influential figures in the history of nature documentaries, Alan had moved from England to Kenya shortly after his birth and spent his life there. His work had been syndicated worldwide for over thirty years, in the course of which he had been bitten by numerous animals, among them a python, a hippopotamus, and a puff adder. When a leopard bit him twice in the buttock, the Serengeti’s chief park warden jokingly told him, “You know you’re not allowed to feed animals in a national park.” A mountain gorilla also bit him while he was filming in the Virungas for the Dian Fossey biopic Gorillas in the Mist. In her book by the same name, Fossey describes how Alan drove her from Kenya to her first research camp site in the Virungas and helped her get set up. Sally had coordinated his arrival so that he could evaluate how well habituated and accessible the bonobos here were for the ecotourism company Abercrombie & Kent. At seventy-five, he was tall and strong-looking, with gray-white hair, a goatee, and glasses.

The trackers as well as Sally, Michael, Alan, and I crowded into the Land Rover together, and it took us through the forest, going slow because of Alan’s back, which had titanium rods in it from two helicopter crashes during his years of filming. The headlamps weren’t working well on this vehicle either, so one of the trackers held a flashlight out the window. After fifteen minutes of grinding our way uphill and rolling through deep ruts, we stopped in front of a village and got out. There was a faint smell of woodsmoke as we walked past the dark mud huts, embers glowing beyond a doorway.

When we came to the edge of the forest, the head tracker took the lead. In his forties, Léonard Nkanga Lolima was a slight man, with a round, faintly feline face. Though he was not imposing, his gaze was unwavering, and he directed the trackers with reserved, almost imperceptible gestures, his quiet authority reassuring. He moved silently as we followed him into the smothering dark of the forest, along a narrow path. When I first met him a few days before and sat down to interview him about his work as a tracker, I was nervous. Having read Paul Raffaele’s account of visiting Kokolopori in Among the Great Apes, I knew that Léonard believed Raffaele to be a sorcerer and feared him. The book offered no indication as to what Raffaele might have done to appear that way, but whatever it was, I didn’t want to do the same. I must have come across as excessively polite and cautious, since Léonard later made efforts to speak to me on a number of occasions, as if to reassure me. Finally, I couldn’t resist asking about Paul Raffaele, and when I did, a cautious, angry look came into Léonard’s eyes. He and the others explained that Raffaele showed them a photo of himself holding a large snake. I knew the image; it was his book’s author photo, in which an anaconda is wrapped around him. But for the Bongandu, nothing could be worse, as snake venom kills people, especially children, every year. They could conceive of no reason for a man to toy with snakes in this way, or—worse—to reveal his power to them, as if threatening them. The explanation surprised me and made me realize how easy it is to overlook a foreign culture, to project one’s own values on another and speak before getting a sense of the person spoken to. Raffaele is an experienced traveler, and it’s a mistake anyone could make.

The foliage on either side of the trail was nearly impenetrable, and I kept my headlamp aimed just before my feet so as not to trip on roots or branches. It had rained all night, the first rain since our arrival in Djolu. A nimbus of mist hung about tree trunks, and after half an hour, the sky began to pearl, dawn infusing low clouds.

Only when we passed small slash-and-burn tracts along the path could I see the outline of treetops. Often, where the dense forest had been cut away, oil palms, native to West and Central Africa, grew in the openings. One nearly blocked the trail, its wet fronds brushing my shoulders. Then we were back in the dense forest, mushrooms along a rotting log like a line of white disks in the dark, vines as thick as my arms dangling from trees.

For a while, the footpath was deep and narrow, cut by years of rain, no wider than my boot, and I had to place my feet carefully, one in front of the other, to keep from tripping. The weeds were shoulder-high, pushing in from either side, soaking my sleeves. I had yet to put my poncho on, the drizzle too faint to be bothersome and the heat of my body drying me.

Suddenly, a large white moth was flying just above my right shoulder, keeping pace, following my headlamp’s gauzy beam through the humid air. It fluttered off, vanished. The ground before me dropped, descending steeply toward a stream, and when I glanced up from my feet, I had a vista of the exposed, rising forest on the opposite slope. The trees reared up, immense, pale pillars lifting the dark canopy high against a faintly silver sky.

When Léonard motioned us to stop, we had been walking for over an hour. We sat along a log. Gray light filtered down. We put on our ponchos as the drizzle intensified, seeping through the canopy and gathering on the bottoms of branches in large drops that plummeted the distance to strike loudly against the dead leaves of the forest floor.

Léonard told us that the bonobos had made their nests in the top of a tree bigger and higher than the others, a dense weave of vines hanging from it, like the tangled rigging of a ship. A hundred feet up, the trunk forked and then, higher, forked again, each branch as big as the trunks of nearby trees.

Bonobos’ nests serve an important role in the rainforest ecosystem. As a group travels each day, sometimes as many as seven miles, they consume large quantities of leaves and fruit. Almost every evening, they make new nests, pulling branches together, snapping or just bending and weaving them, exposing the forest floor to the sun. In the night and morning, they defecate, and their droppings fall to the earth, carrying seeds that have passed through their guts largely intact. The seeds are mixed with fertile roughage and their hulls have been abraded by the digestive tract, making them more ready to sprout. In the patches of sunlight where the nests broke the canopy, the seeds grow more easily, taking root in the rainforest’s thick loam. Because the bonobos travel so widely within their territory, they spread seeds, contributing to biodiversity. Without the bonobos—as well as the numerous other rainforest animals, from elephants, to buffalos, to birds—certain tree species might even go extinct.

With dawn, the forest began to reveal its contents, the stony phallic mounds of termites, some mushroom-shaped, others veritable lingams, a foot to three feet tall. Mushrooms grew from rotting sticks, some white and pin-shaped, others vivid orange saucers. A few gray caterpillars with red and black markings crawled on my poncho, others on leaves. Called mbindjo, they, like mpose, provide protein for both the locals and the bonobos.

The clouds glowed, sunlight struggling through, and as we stared at the dense canopy, the sky was a million specks of mercury, the leaves like lacework around larger openings.

Branches began to shake, drops of water falling. A bonobo’s arm weaved out briefly. A figure walked along a branch with a humanlike swaying of its shoulders. An adult bonobo gave its high-pitched hoot, and then a baby wailed, very much like a human baby, but just two or three times before it fell silent.

The canopy again ceased to move. Léonard told us that the bonobos would wait in the highest branches for the sunlight to warm them. Like us, they are slow to rise on rainy mornings. I pictured them seated on the immense branches, at the summit of this tree rising above the rest of the forest. They stared out over the green ocean, slowly blinking their black and luminous eyes. It was hard not to wonder at that primeval experience, of a creature so similar to ourselves living in such absolute elements, gathered with its family, sitting in peace at the line of forest and sky.

Staring up, I got vertigo and needed to look down for a moment before I could take a step. Above me, the dark interlacing canopy seemed liquid, the sky shining through like a reflection of light cast on the deep, shadowed water of a well. Each of the bonobos’ movements caused the leaves to shimmer as if a pebble had been dropped in.

We waited for over an hour. Alan identified the calls of birds for us, the chiming of the emerald cuckoo and the low mournful fluting of the chocolate-backed kingfisher. Léonard explained that this particular community of bonobos had twenty-five members, three adult males, twelve females, six adolescents (three of each sex), and four babies.

Eventually, the branches began to shake in earnest. A large piece of deadwood fell and thudded against the loam. The bonobos all seemed to be awake, but waiting. The dark circles of their nests were barely visible.

They might have been feeding on mbindjo in the trees, Léonard told us. Along a high branch, a female walked on all fours, the pink bulge of her vaginal swelling clear even at this distance, a child following behind. Normally, bonobo infants cling to their mothers until they are four or five years old, but this one was larger, more independent.

Sally opened a bag and began passing around power bars and trail mix. This was a tradition she had begun, that visitors and trackers ate together, and she told me that it never failed to intrigue the bonobos. Food sharing is central to their culture, and often, when they come upon plentiful amounts, they have sex in excitement before sharing it. Sally preferred eating together rather than simply following bonobos with binoculars and cameras, which to her felt aggressive, as if we had come there just to take something.

“It’s better to draw them to us,” she said. “I’ve noticed that the demeanor of the people who are in the forest changes how close the bonobos come, and how long they stay with us. They love seeing humans share the way they do.”

There was faint hooting in the canopy, flurries of movement as the bonobos moved closer to find out what we were eating and how we were passing the food around.

A bonobo stood on two legs and, holding a branch above it for balance, turned its broad head to stare down, its posture evoking that of a tightrope walker paused, contemplating the world below. Then it reached higher into the foliage, stretching the sinews of its long body before it lifted itself out of sight.

After we finished eating, we watched the silhouettes move off along the canopy, leaping at times. One used its body weight to make the branch it was on sway closer to a branch of the next tree, before it grabbed hold and crossed over. Léonard told us that the bonobos most often traveled on the forest floor; crossing from tree to tree required too much effort.

He again directed his trackers quickly, with slight gestures. Even as we spread out, he led us through the undergrowth, off the path now, pausing to break branches and place leaves so that, in case one of us wandered off with a tracker to take photos, the tracker could read the signs and we could all meet up again.

I’d bought my poncho online, assuming its soft waterproof material made from recycled plastic would be ideal for use in the rainforest. But I immediately saw its flaw. Unlike the smooth plastic ponchos that the others wore, mine caught every thorn in its weave. As I peeled briars away, wire-thin vines snared my boots and torso, and occasionally I had to stop and untangle myself as if from a net.

Alan pointed out a caterpillar with long white whiskers and a black head, a four-tuft Mohawk of black and white bristles on its back, and I wondered which of the more exotic butterflies this one became. It was the most spectacular caterpillar I’d ever seen.

Léonard warned me that it probably stung, that the prettier they were the more likely they were to be dangerous. He motioned us farther through the forest, the occasional rotten log compressing like a sponge beneath my boot.

Though slow to reveal themselves, the bonobos began to make more appearances, peeking down through the foliage with curious eyes, red lips vivid in their black faces. They had the taut, muscular arms of athletes, and their bodies were particularly graceful. As they studied us, they curled their long fingers around branches and tree trunks. We crept through the foliage, trying to see them more closely.

The large infant I’d noticed earlier hung for a while in an opening in the branches, eyes laughing, clearly entertained. He was suspended with his potbelly protruding as he examined us: strange creatures, our faces lifted. He glanced around with fascination, then disappeared into the foliage, and moments later an adult male swung to a nearby tree, one hand holding the trunk. He watched with the same curious and pleased air as the infant, lowering his eyebrows and pushing his lips forward, then faintly, sweetly simpering, as if unable to decide what face to show us. The black hair on his chest and the insides of his arms was thinner than that on his head and back, and his large pale testicles and thin pink penis showed between his thighs.

He studied us for a long time, occasionally glancing off, presenting his profile. He was an adult, but there was something particularly youthful about him, lighthearted, as if he hadn’t taken on responsibility for his group yet, or simply knew that we were no threat.

The light through the clouds brightened, glittering against the moisture in his hair and fur, giving him a silver nimbus. He seemed so pleased looking at us that if he’d broken into laughter, I wouldn’t have been surprised. He shook his head and reached up, his body not much smaller than a human’s but more pliable and dynamic, and then he climbed out of sight.

These bonobos had been habituated by trackers who monitored them daily, but they were far from tame. I had observed chimpanzees at the Ngamba Island sanctuary in Uganda, and their muscular presence and aggressive gazes gave me little inclination to go near them. Signs warned that if one of them escaped the enclosure all visitors should stand in the lake, since chimpanzees are afraid of going into water. Alan had told me that chimps made him feel as if he were passing a street gang and had to avoid eye contact. This aggressive, dominant attitude appeared absent in bonobos, only the older females somewhat authoritative. They showed little interest in us even as the adolescent males watched us with wide eyes.

Following the Ekalakala group, named for a nearby stream, we wandered through the forest, taking pictures. Léonard knew their patterns. Each time he took me aside and told me to wait somewhere, I didn’t know what to expect. I sat and watched the forest. Nothing moved. The others had wandered off, and I became convinced that Léonard was mistaken, that he was telling me to sit there for no good reason. Then, sometimes fifteen or twenty minutes later, a bonobo appeared almost directly before me.

At one point, Léonard suggested that Alan and I wait near a fallen tree, which had created an opening in the undergrowth where the sun shone into the forest. We crouched for at least twenty minutes before two bonobos came through the canopy. One swung himself down to the log and scampered across. But the other made a more dramatic entrance. He hugged the top of a thin tree and let it bend under his weight until he was upside down and his head was almost to the log. Then he flipped himself to his feet and released the tree, letting it snap back up. He sat, assuming pose after pose, looking at the sky, the ground, over his shoulder and back, then just stared off as we clicked photos.

He appeared deep in contemplation, though I had the sense that he knew exactly what we were doing, and wanted to be seen in his best light.