Читать книгу Prudence Crandall’s Legacy - Donald E. Williams - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2 : Liberators

In the fall of 1831 a young writer sought out William Lloyd Garrison at his Boston office of the Liberator. Maria W. Stewart sat patiently as Garrison read her essays. The first concerned religious faith and “devotional thoughts and aspirations.”1 Garrison’s interest grew as he read other essays by Stewart that called for an end to slavery and revealed the “intelligence and excellence of character” of an exceptional writer.2 Garrison told Stewart he would print some of her essays in the Liberator—and publish the entire collection of her work as a short book.

Maria Stewart’s book likely was the first political manifesto written by a black woman in America.3 “Ye daughters of Africa, awake!” Stewart wrote. “No longer sleep nor slumber, but distinguish yourselves. Show forth to the world that ye are endowed with noble and exalted faculties.”4 Garrison published Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality: The Sure Foundation on Which We Must Build in 1831, and promoted Stewart’s book in the Liberator. “The production is most praiseworthy,” Garrison wrote, “and confers great credit on the talents and piety of its author.”5

Stewart found a unique collaborator in Garrison, a white man willing to publish the opinions of a black woman at a time when the views of women of any color, on any serious subject, were not considered worthy of space in a newspaper.6 Even the progressive Garrison, however, had difficulty in 1831 considering women as journalistic equals. He printed Stewart’s essays in a separate “Ladies Department” section of the Liberator.7

Stewart wrote a brief biography of her life in the introduction to her book. Born in 1803 in Hartford, Connecticut, Maria Miller became an orphan at the age of five and lived with a minister’s family. She helped with household chores and learned scripture, but longed for a more formal education.8 At fifteen, she left the minister’s family and supported herself through various domestic servant jobs. “How long shall the fair daughters of Africa be compelled to bury their minds and talents beneath a load of iron pots and kettles,” Maria wrote.9 During those years she attended church schools and developed an advanced ability to read and write.

She traveled to Boston and met James W. Stewart.10 James was forty-four when he married twenty-three-year-old Maria Miller on August 10, 1826. James served in the War of 1812 and ran a lucrative business of “fitting out,” or finishing, the interior quarters of newly constructed whaling and fishing vessels.11 As a measure of the couple’s standing in the community, Reverend Thomas Paul performed James and Maria’s wedding.12 Paul helped create the first independent black Baptist churches in the United States. His congregation met at the African Meeting House in the Beacon Hill section of Boston—the center of activity for the black community and the abolitionist movement. James and Maria Stewart’s wedding likely took place at the African Meeting House.

At the beginning of December 1829, three years after they married, James Stewart became seriously ill and drafted his will. He died on December 17, 1829.13 Maria and James had no children, and James left a considerable inheritance to Maria. When Maria brought an action in probate court to settle her husband’s affairs, however, four white businessmen filed a separate action featuring a fraudulent Mrs. James Stewart. They succeeded in stealing James Stewart’s estate and left nothing of value for Maria Stewart.14 A friend described Stewart’s experience: “I found her husband had been a gentleman of wealth, and left her amply provided for; but the executors literally robbed and cheated her out of every cent.”15 This was not an unusual fate for the widows of black men. Black businessman and activist David Walker wrote about such cases in Boston: “When a man of colour dies, if he owned any real estate it most generally falls into the hands of some white person. … The wife and children of the deceased may weep and lament if they please, but the estate will be kept snug enough by its white possessor.”16

The meager opportunities available to black women frustrated Stewart: “How long shall a mean set of men flatter us with their smiles, and enrich themselves with our hard earnings?”17 For Stewart, the discussion of ending prejudice and discrimination too often focused on the rights of men. “Look at many of the most worthy and most interesting of us doomed to spend our lives in gentlemen’s kitchens,” Stewart wrote.”18 “Have you prayed the legislature for mercy’s sake to grant you all the rights and privileges of free citizens, that your daughters may rise to that degree of respectability which true merit deserves?”19

Beginning in 1832 Stewart delivered speeches on the issues of slavery and prejudice, often before mixed gatherings of both black men and women. This earned her both admiration and contempt; some in her own community did not appreciate receiving a call to action from a woman.20 Women were expected to refrain from public speaking and avoid controversial issues.

William Lloyd Garrison’s decision to print her speeches in a booklet and in the Liberator bolstered Stewart’s efforts to challenge her community on a broad scale. A network of volunteer agents distributed the Liberator throughout New England.21 These included many black individuals and families who promoted the newspaper and solicited subscriptions.22 By 1832 several thousand subscribers received the weekly Liberator.23 The number of readers was significantly greater, as subscribers passed along copies to family and friends. Stewart’s call for equality for blacks and women commanded attention from many thousands of readers, both black and white.

Sarah Harris, a young black woman who lived in Canterbury, Connecticut, may have read Stewart’s essays in the booklet printed by Garrison, as well as the other articles concerning emancipation and equal rights in Garrison’s Liberator. The local agent and distributor for the Liberator in northeastern Connecticut was William Harris, Sarah’s father. William Harris traveled from the West Indies to the United States and settled in Norwich, Connecticut. He married Sally Prentice in 1810; together they raised twelve children and moved to Canterbury, where William made his living as a farmer.24

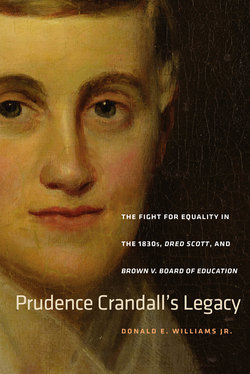

18. Harris family sampler, which states, “Sarah … was born April 16, 1812.” Sarah Harris was Prudence Crandall’s first black student.

Harris family sampler. Courtesy of the Collection of Glee Krueger.

The Harris family was part of a growing network of literate and informed black families who aspired to more than what the prejudices of the day permitted. Academies for blacks did not exist in Canterbury or anywhere else in Connecticut. William Harris was frustrated by what he saw as deliberate barriers to opportunities for blacks.

“The free blacks are prevented by prejudice and legal restraints from resorting to innumerable modes of supporting themselves and their families by honest industry,” a commentator in Connecticut noted. “Our colleges and seminaries exclude them; the professions are sealed against them … they are prohibited, if not by law, yet in fact, from pursuing anything but menial occupation.”25 Reading the Liberator helped Harris imagine a country with equality for all. Harris thought so much of the Liberator and Garrison that he named one of his sons William Lloyd Garrison Harris.26

Maria Stewart’s promotion of education and self-improvement would have resonated with William Harris and his daughter Sarah. “Many bright and intelligent ones are in the midst of us; but because they are not calculated to display a classical education, they hide their talents behind a napkin.”27 Stewart wrote that there were “no chains so galling as those that bind the soul,” and encouraged her readers to claim their rights.28 “Possess the spirit of independence,” Stewart said. “Possess the spirit of men, bold and enterprising, fearless and undaunted.”29

Mariah Davis, a close friend of Sarah Harris, worked at Prudence Crandall’s school as a servant, or as Crandall referred to her, a family assistant.30 Mariah was engaged to Sarah’s brother, Charles Harris, and shared the Harris family’s interest in education for black men and women. When Mariah finished her daily chores at the school, she occasionally sat in on classes with the white girls.31 She read the Liberator and once gave a copy to Prudence Crandall; thereafter, Crandall faithfully read Garrison’s newspaper.32

Sarah Harris dreamed of becoming a teacher.33 On a visit to Crandall’s school to see Mariah in September 1832, Sarah summoned the courage to ask Prudence Crandall if she could enroll as a student and attend class full-time.34 Sarah said she did not need to board as she could walk each day from her father’s farm. Her father could afford to pay the tuition. Sarah told Crandall about her desire “to get a little more learning, if possible enough to teach colored children.”35 Sarah also understood the magnitude of the request. “If you think it will be the means of injuring you, I will not insist on the favor,” Sarah told Crandall.36

Crandall knew that no one objected when Mariah Davis sat in on classes after she finished her work. Mariah, however, was a school employee, not a student. The distinction was obvious and important. Crandall listened carefully to Sarah’s request but did not give an answer. She told Sarah she needed time to think it over.37

Prudence Crandall considered the potential reaction of her family, the town fathers, the school’s Board of Visitors, and her students and their parents. Crandall depended on the success of her school in a number of ways. Her family had invested in the school, and a significant mortgage on the schoolhouse was still outstanding. She employed her sister Almira at the school. The school provided Crandall with the opportunity for leadership and a career path with the potential for long-term financial security.

Crandall’s first inclination was to deny Sarah’s request. She later confided her doubts to Rev. Samuel May, who became a staunch supporter and teacher at her school. “Miss Crandall confesses that at first she shrunk from the proposal,” May wrote, “with the feeling that of course she could not accede to it.”38 Crandall had succeeded against all odds as a single woman in establishing a well-respected school. “I am, sir, through the blessing of Divine Providence, permitted to be the Principal of the Canterbury Female Boarding School,” she once wrote. “Since I commenced I have met with all the encouragement I ever anticipated, and now have a flourishing school.”39 Weeks passed and Crandall continued to ignore Sarah Harris’s request. Despite all of the expedient reasons to be clear with Sarah and simply refuse her request, Crandall remained silent, conflicted, perhaps hoping that Sarah would not persist.

Mariah Davis continued to share copies of the Liberator with Prudence Crandall. In the summer and fall of 1832, articles appeared regarding the rights of women. William Lloyd Garrison wrote that advocates of immediate emancipation often overlooked the ability of women to assist in the cause. Garrison wrote that the cause of humanity is “the cause of woman,” and women “undervalue their own power.”40 Without the assistance and hard work of women, Garrison wrote, social progress would be “slow, difficult, imperfect.”41

An essay by Maria Stewart in the Liberator encouraged activism that combined religious faith with the fight against prejudice and discrimination. “It is that holy religion, which is held in derision and contempt by many, whose precepts will raise and elevate us above our present condition … and become the final means of bursting the bands of oppression.”42 Stewart noted that black men and women lacked the opportunity to receive an education, and called for change. “It is high time for us to promote ourselves by some meritorious acts,” Stewart said. “And would to God that the advocates of freedom might perceive a trait in each one of us, that would encourage their hearts and strengthen their hands.”43

In September, Maria Stewart delivered a lecture at a meeting of the New England Anti-Slavery Society, at Franklin Hall in Boston. Garrison published her speech in the Liberator. Stewart said that black women lacked opportunity because employers feared “they would be in danger of losing the public patronage” if they hired blacks. “Such is the powerful force of prejudice. Let our girls possess whatever amiable qualities of soul they may; let their characters be fair and spotless as innocence itself; let their natural taste and ingenuity be what they may; it is impossible for scarce an individual of them to rise above the condition of servants. … Owing to the disadvantages under which we labor, there are many flowers among us that are ‘born to bloom unseen, and waste their fragrance on the desert air.’”44 Mariah Davis and Sarah Harris read the Liberator throughout the summer and fall of 1832, as did Prudence Crandall.45

Sarah did not let the matter drop. After she waited for what she considered a reasonable amount of time without receiving an answer, she made “a second and more earnest application” to Prudence.46 This time, Crandall gave her a definitive answer. “Her repeated solicitations were more than my feelings could resist,” Crandall said. “I told her if I was injured on her account I would bear it—she might enter as one of my students.”47

Prudence Crandall’s decision to admit a black student to her school was part of a growing and uncertain transformation in America. Black writers such as David Walker and Maria Stewart demanded an end to slavery and championed civil rights and citizenship for all free blacks. The first national antislavery convention of those who favored immediate emancipation was held in Philadelphia in December 1833. William Lloyd Garrison wrote that blacks were entitled to the same rights and privileges as whites and deserved equality in American society. Those views were far outside the mainstream of public opinion in the 1830s, but a perceptible shift was under way.

At the end of 1829, David Walker published a book that created a fierce debate about the role of blacks in the effort to end slavery. Walker’s Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World created great interest in the black community and a firestorm of protest elsewhere; it also influenced those who worked with Prudence Crandall, including William Lloyd Garrison. What caught the public imagination was Walker’s sensational call to arms; he said slaves should take up weapons and fight for their freedom just as American colonists fought for their independence from Great Britain. “Kill or be killed,” Walker said.48 One Boston newspaper noted the popularity of the Appeal in the black neighborhoods of Boston. “They glory in its principles as if it were a star in the east, guiding them to freedom and emancipation.”49 The editors of the Boston Daily Evening Transcript did not believe that a black man wrote the Appeal and speculated that the author was “some fanatical white man.”50 The Niles Register summarized Walker’s book as “fanaticism, tending to disgust all persons of common humanity.”51 The Richmond Enquirer called it “the most wicked and inflammatory production that ever issued from the press.”52

In the Appeal, Walker attacked a movement that had gained widespread popularity in the 1820s and purported to solve the problems of slavery and discrimination. Many of Prudence Crandall’s supporters, including William Lloyd Garrison, initially supported the American Colonization Society (ACS) and its goals. The ACS was formed by a group of white citizens in 1817, including Senator Henry Clay, Reverend Robert Findley, and Francis Scott Key. The ACS sought to slowly liberate and “colonize” blacks in the United States by sending them back to Africa to the newly created country of Liberia. The ACS proposed a gradual end to slavery with an undetermined end date in order to placate the South and preserve the union of the states. Colonization gained significant support throughout the 1820s and 1830s.53

The ACS won supporters in both the North and South. Slave owners understood that removing the free black population would strengthen the institution of slavery by eliminating a competing source of cheap labor, thereby increasing the value of slaves. Slave owners successfully shifted the focus of colonization from ending slavery to sending free blacks back to Africa. They helped transform a movement that began as a means to free slaves into an enterprise that suited the needs of both slavery opponents and slave owners.54

The fierce opposition to colonization by David Walker and other black leaders, however, gave William Lloyd Garrison and other abolitionists reason to question the ACS. Walker equated colonization with banishment and surrender to the idea that those of a different race could never expect equality in America. “Will any of us leave our homes and go to Africa? I hope not,” Walker wrote. “Let no man of us budge one step, and let slave-holders come to beat us from our country.”55 Walker’s direct influence on Prudence Crandall is uncertain. She had access to some of his writings through the Liberator, but she most likely would have disagreed with Walker’s willingness to embrace violence. Crandall’s views, however, mirrored Walker’s regarding the pursuit of equality through education. “For coloured people to acquire learning in this country makes tyrants quake and tremble on their sandy foundation,” Walker wrote. “The bare name of educating the coloured people scares our cruel oppressors almost to death.”56

Crandall drew on her Quaker roots and her new Baptist fervor to do God’s will when she agreed to enroll Sarah Harris as a student. She considered whether Christians should “treat one with unkindness and contempt, merely to gratify the prejudices of the rest.”57 The articles and essays in Garrison’s Liberator helped refine and stimulate Crandall’s sense of right and wrong pertaining to racial prejudice.58 Crandall acknowledged that the Liberator strongly influenced her decision to admit Sarah. She specifically noted how it exposed the “deceit” of the American Colonization Society’s plan to return blacks to Africa, and convinced her of the wisdom of immediate emancipation of the slaves.59 Crandall concluded, “Education was to be one of the chief instruments by which the condition of our colored population is to be improved.”60

Maria Stewart likely influenced Crandall in her decision to admit Sarah Harris. “Shall it any longer be said of the daughters of Africa, they have no ambition, they have no force? By no means,” Stewart wrote. “Let every female heart become united, and let us raise a fund ourselves; and at the end of one year and a half, we might be able to lay the corner stone for a building of a High School, that the higher branches of knowledge might be enjoyed by us; and God would raise us up …”61

In addition to the considerations of faith and equality, Crandall truly liked Sarah Harris as a person. Crandall wrote that Sarah was “correct in her deportment … pleasing in her personal appearance and manners.”62 Crandall was moved by Sarah’s desire to become a teacher.

At first, there was no significant change at the school. Sarah enrolled and joined the other students in class. The students knew Sarah not only through her visits to the school, but also through her family’s membership in the local Congregational Church at Westminster, where “racial background seems to have offered no barrier to Sarah’s acceptance as a member of the predominantly white congregation.”63 No one objected when young black children attended the local district school, in part because of the young age of the children and the small number of black students.64 The white women at Crandall’s school accepted Sarah as a fellow student without incident or complaint.65

It did not take long for word of the school’s new black student to spread among the adult population of Canterbury. Crandall expected some criticism, but thought it “quite as likely that they would acquiesce, if nothing was said to them on the subject, as most of them were acquainted with the character of the girl.”66 The parents of the other students did not react favorably. Some approached Prudence’s father and said they would remove their daughters from the school.67 Crandall’s older brother, Hezekiah, told Prudence that business at his cotton mill had declined because of her decision to admit Sarah Harris.68 The patrons of the school told Crandall that, unless she dismissed Sarah Harris, the school would lose many students.69 “By this act,” Crandall conceded, “I gave great offence.”70

As townspeople increased pressure on Crandall to reverse her decision, she responded with greater determination to keep Sarah as a student. The wife of an Episcopal minister told Crandall that she must dismiss her black student or else her school would fail. Crandall replied, “that it might sink, then, for I should not turn her out!”71 Crandall presented herself with firmness and certainty when publicly challenged, but privately she had grave doubts about the survival of her school. “I very soon found that some of my school would leave not to return if the colored girl was retained,” Crandall wrote.72

Only twelve months had passed since the citizens of Canterbury had embraced Prudence Crandall’s school with enthusiasm. Now Crandall faced limited and troubling options. She could dismiss Sarah Harris or wait for the parents to withdraw their daughters and close her school. Under mounting pressure she thought of an alternative. She would not dismiss Sarah Harris. “Under the circumstances,” Crandall said, “I made up my mind that, if it were possible, I would teach colored girls exclusively.”73

The decision to remake the school and teach only black women was made by Prudence Crandall alone. She did not seek input from her family, friends, or the school’s patrons.74 She knew, however, that she could not pursue this change by herself. Crandall needed help recruiting black students from throughout New England. Her plan demanded great effort and courage, and she did not have much time.

Crandall reached out to a person she had never met but who had influenced her greatly. On January 18, 1833, she wrote to William Lloyd Garrison, “I am to you, sir, I presume, an entire stranger, and you are indeed so to me save through the medium of the public print.”75 She explained that she served as principal of the Canterbury Female Boarding School, and asked Garrison what he thought of her idea of “changing white scholars for colored ones.”76 She did not mention her decision to admit a black woman, Sarah Harris, as a student, and the adverse reaction in the community. Crandall provided no other clue as to why she was considering such a dramatic change in the mission of her school other than to say, “I have for some months past determined if possible during the remaining part of my life to benefit the people of color.”77 She described the necessary number of students and the amount of tuition they needed to pay in order to meet the expenses of the school, and she also laid out a strategy to recruit students from Boston and cities throughout the Northeast.

Months and years later, opponents of her school claimed the idea for Crandall’s school for black women came from Garrison and that Crandall was merely a pawn of radical abolitionists. There is, however, no evidence that anyone other than Crandall originated the idea of transforming her school. When Crandall thought of the idea in response to the outcry after she admitted Sarah Harris, she broached the idea with Garrison in order to enlist his assistance—he did not know her or contact her; she reached out to him.78

“Will you be so kind as to write by the next mail, and give me your opinion on the subject,” Crandall asked Garrison. “If you consider it possible to obtain twenty or twenty-five young ladies of color to enter the school for the term of one year at the rate of $25 per quarter, including board, washing, and tuition, I will come to Boston in a few days and make some arrangements about it. I do not suppose that number can be obtained in Boston alone; but from all the large cities in the several States I thought that perhaps they might be gathered.”79

Crandall realized the Liberator had the potential to link allies together, facilitate a network of financial support, and provide the means for achieving specific goals. Crandall’s letter impressed Garrison, and he agreed to a meeting in Boston. Crandall discovered a unique ally in Garrison.

William Lloyd Garrison lived a life filled with uncertainty and risk. Born in Newburyport, Massachusetts, on December 12, 1805, Garrison had an older brother and sister, James and Caroline, and a younger sister, Maria Elizabeth. His parents, Abijah and Maria Garrison, had moved from Nova Scotia to Newburyport before Garrison was born. Abijah was a sailor, and the economy in Nova Scotia had collapsed. “The scarcity of bread and all kinds of vegetables was too well known in this part of Nova Scotia,” Abijah wrote.80 He could not find work. Newburyport, a seaside town with a busy harbor, had a thriving economy. In Massachusetts, Abijah found work sailing as far south as Guadeloupe to pick up shipments of sugar, oranges, and other tropical cargo.81

By the time Garrison was three years old, Portland, Maine, surpassed Newburyport as the center for shipping and shipbuilding. In 1807 a federal embargo forbidding the export of American cargo, combined with declining prices for fish, quickly wrecked the economy of Newburyport.82 Garrison’s father could not find work, and the family struggled to survive. Garrison and his siblings often were desperate with hunger. Garrison’s five-year-old sister Caroline ate a poisonous plant, and the family watched helplessly as she convulsed and died. Shortly thereafter Abijah left and never returned.83 Garrison’s family survived on income his mother Maria earned caring for infants of families connected with the Baptist church they attended. The two boys, James and William Lloyd, known to his family as Lloyd, sold homemade candy on the street, and the family ate leftover food from relief kitchens.84 With help from friends and the church, they stayed together as a family.

On the evening of May 13, 1811, a fire began in a stable near the Newburyport harbor. Winds quickly carried it to the commercial buildings, docks, and wharves of Newburyport. As residents fled, they carried their belongings to buildings they thought were safe, such as the Baptist meetinghouse. A shift in the wind, however, put the entire town at risk. For the rest of his life, Garrison remembered when as a five-year-old boy he heard the roar of the fire sweep through the city and was held aloft in the night to see flames shooting out of windows and through the roofs of nearby homes. Garrison and his family joined those in the streets who had lost everything; they tried to make their way to safety in the midst of “the incessant crash of falling buildings, the roaring of chimneys like distant thunder, the flames ascending in curling volumes from a vast extent of ruins,” and air filled with a shower of fire and ash.85 It was a horrifying disaster that devastated Newburyport and the Garrison family. In all, the fire destroyed 250 buildings, including all of the structures along the harbor, the Baptist church, and all homes in the sixteen-acre heart of the town. Hundreds of residents, including Garrison’s family, were homeless.86

Without a roof over their heads and without the support from the Baptist church, Garrison’s mother left Newburyport with her son James to live with friends in Lynn, Massachusetts. Lloyd and his younger sister Elizabeth stayed in Newburyport in the care of a neighbor. Mrs. Garrison promised to send money to help support Lloyd and his sister, but the money was never sent, even after his mother secured a job. This arrangement continued until Garrison’s eighth birthday, when an elderly couple, Ezekiel and Salome Bartlett, agreed to provide for the boy.87 The Bartletts were poor; caring for Garrison was an act of Christian charity that placed additional stress on their already meager family budget. Garrison attended school in the fall of 1814 when he was nine, but soon left to take whatever odd jobs he could find to help them all survive.88 He ran away once, traveling twenty miles on foot until a mailman picked him up and returned him home by wagon.89

His mother invited Lloyd to come live near her in Lynn with the family of Gamaliel Oliver, a shoemaker.90 Lloyd’s brother, James—who was only four years older than Lloyd—lived on his own and spent what little money he earned on alcohol. In the next four years Lloyd moved south to Baltimore and then back to Newburyport. He was shipped off to a cabinetmaker in Haverhill. All the moving around took a toll on Garrison. At thirteen years old, he ran away from the cabinetmaker and returned to Newburyport without a plan for his future.91

The Newburyport Herald had a sign in the office window, “Boy Wanted,” and Garrison walked through the door. In the fall of 1818 he began a career in publishing that lasted the rest of his life. It did not begin well. He was hired for the position of “printer’s devil.” The primitive technology of the time required printers to light a fire underneath a pot of varnish and lampblack until it became a boiling, sticky cauldron of black ink. The printer’s devil then applied the ink by hand to the metal type with sheepskin made pliable by soaking it in pails of urine. It was Garrison’s job to make the ink and soak the sheepskin.92 He thought of running away yet again, but stayed on hoping to advance from this bottom level of the newspaper business.

Garrison focused on learning his job and doing it well, and his superiors rewarded him for his hard work. He quickly advanced through the ranks of newspaper production and became an expert typesetter. He impressed the publisher of the Newburyport Herald, Ephraim Allen, with his talent and work ethic. Allen saw in Garrison some of the same ambition and determination that Allen possessed when he began his own career. Allen had purchased the Herald in 1801 when he was twenty-two years old; the newspaper went to press two days per week and had a small circulation. Allen served as the printer, editor, reporter, and carrier of the paper.93 Allen’s news-gathering technique consisted of traveling by stagecoach to Boston, purchasing all the newspapers he could find, and copying articles from other newspapers.94 Twenty years later the Herald was the leading newspaper in Newburyport with dozens of employees.

Allen promoted Garrison to the position of apprentice and invited him to board at Allen’s home. Ephraim Allen had six children, including a boy Garrison’s age. Garrison discovered a world beyond the reach of poverty. Parents and children all lived together. No one went hungry. Garrison took advantage of the family’s library and began an intense effort to educate himself; he read Shakespeare, Milton, and contemporary literature.95

By the beginning of 1823, Garrison supervised the production of the Herald. In 1826 he pursued an opportunity to purchase the Northern Chronicler, a rival newspaper in Newburyport. Ephraim Allen loaned Garrison the money needed for the purchase. Garrison was twenty years old. Allen and the staff of the Herald gave Garrison a congratulatory send-off on March 17, 1826. Garrison renamed his newspaper the Free Press and immediately plunged into local politics.96

The race for the region’s congressional seat generated a fierce battle of editorials. Garrison backed the Federalist incumbent, while Ephraim Allen supported Caleb Cushing, a former Herald employee. Garrison and Allen had disagreed on other issues in their respective newspapers; however, this time the sparring became personal and consequences ensued. On September 21, 1826, with no warning, Garrison sold the Free Press to a newspaperman who quickly aligned it with the editorial point of view of the Herald. Garrison said he sold his newspaper for personal reasons, but one historian concluded that “it seems inescapable” that Ephraim Allen ran out of patience with his not so deferential protégé and called in his loan.97 Garrison learned a bitter lesson in the ways of business and politics. After only six months he lost his newspaper. As a small consolation, Caleb Cushing lost the race for U.S. Congress.98

Garrison left Newburyport for Boston and took up residence in a boardinghouse owned by William Collier, a Baptist minister who published religious newspapers. Collier’s newspapers promoted two popular social movements: the temperance campaign to curb alcohol consumption and the new religious revivalism. Collier asked Garrison to manage the National Philanthropist, a temperance newspaper with the slogan, “Moderate drinking is the downhill road to intemperance and drunkenness.”99 While editing the National Philanthropist, Garrison met Benjamin Lundy, a friend of Collier.100

Lundy needed wealthy patrons to help finance his antislavery newspaper, the Genius of Universal Emancipation. Lundy found little support even among progressive businessmen and clergy. Many reformers preferred to concentrate on less-contentious issues such as ridding society of public drunkenness.

Prior to meeting Benjamin Lundy, Garrison considered slavery as one of many issues worthy of reform. Garrison described himself as a friend to the poor, “a lover of morality, and an enemy to vice,” and supported the temperance movement, antigambling efforts, and reform in local politics.101 He had a high opinion of his own potential. “My name shall one day be known to the world,” Garrison wrote in a letter to the Boston Courier in 1827. “This, I know, will be deemed excessive vanity—but time shall prove it prophetic.”102 Lundy’s accounts of the evils of slavery helped Garrison conclude that slavery was the single most important problem in the United States, a moral outrage that demanded opposition and justice.

Garrison impulsively quit his job at the National Philanthropist, hoping to join Lundy in Baltimore. Lundy, however, could not afford to take on a partner, and Garrison scrambled to find another job. He traveled to Bennington, Vermont, to edit the Journal of the Times, a political newspaper created for the sole purpose of supporting John Quincy Adams in his 1828 reelection bid for president. While Garrison was essentially a hired political operative, he did find ways to write about slavery. Garrison attacked Adams’s opponent, Andrew Jackson, and worked slavery into the story line, reminding readers that Jackson owned slaves.103 The rival and well-established Vermont Gazette, which supported Andrew Jackson, accused Garrison of being a paid mouthpiece for the Adams campaign and said the Journal was nothing more than a broadsheet for John Quincy Adams, which was all true. Garrison denied the charges. “The blockheads who have had the desperate temerity to propagate this falsehood have yet to learn our character,” he wrote.104 The Gazette also claimed that Garrison and the Journal supported ending slavery through immediate emancipation, which the Gazette said would ruin the South and the nation. Garrison denied that charge as well. Immediate emancipation was “out of the question,” Garrison wrote.105 On election day, John Quincy Adams won Vermont and all of the New England states, but the South and the Midwest solidly supported Jackson, and Andrew Jackson was elected president. Garrison, still hoping to work with Benjamin Lundy, left the Journal and returned to Boston.

Surviving on a variety of temporary printing jobs, Garrison won an invitation from the Boston Society of Congregational Churches to deliver an address on Independence Day 1829 at the Park Street Church. The American Colonization Society sponsored the event and received donations collected at the service.106 “The American Colonization Society has effected much good,” Garrison wrote, “and deserves unlimited encouragement.”107 Garrison acknowledged, however, that colonization alone could not bring about the end of slavery.

Garrison wanted to utilize the speech to make a name for himself in Boston. He spent weeks working on the text and laying out the evils of slavery. A few days before the address he predicted his speech “will offend some, though not reasonably.”108 His dire financial circumstances provided extra motivation. “I am somewhat in a hobble, in a pecuniary point of view, and must work like a tiger,” he wrote.109 If the speech did not help him find employment in Boston, he told a friend he would return to Newburyport and plead with his former mentor, Herald publisher Ephraim Allen, for a job.110

The Park Street Church, which had seating for more than one thousand parishioners, was nearly full when Garrison delivered his address on the afternoon of July 4, 1829. Garrison startled his audience by demanding not only an end to slavery, but also full citizenship and equal rights for slaves and free blacks. “A very large proportion of our colored population were born on our soil, and are therefore entitled to all the privileges of American citizens,” Garrison said. “Their children possess the same inherent and unalienable rights as ours.”111 He challenged the audience to consider the humanity of the slaves. “Suppose that … the slaves should suddenly become white. Would you shut your eyes upon their sufferings and calmly talk of constitutional limitations?”112

The only significant response to his speech appeared in the American Traveler, a Boston newspaper that summarized Garrison’s speech as a combination of anti-American sentiment and procolonization advocacy. Garrison seemed destined to return to Newburyport. At this low point, Garrison received a letter from Benjamin Lundy. Lundy asked Garrison to join him in Baltimore to help publish his antislavery newspaper. On September 2, 1829, Garrison joined Lundy as the editorial assistant for the Genius of Universal Emancipation.

The differences between the two men were apparent from the outset of their partnership. At twenty-three, Garrison was seventeen years younger than Lundy, yet he had more practical experience in the newspaper trade. He had mastered the mechanics of typesetting and publishing at the Herald and served as the principal writer and editor for the National Philanthropist. While at the Free Press, Garrison drafted most of the articles and editorials without writing them out in advance; he acquired the mental discipline necessary to compose his stories as he set the type. In 1828 Garrison wrote in a more abrasive and fearless style compared to Lundy. Lundy once embraced slashing attacks on slavery and slaveholders, and paid a severe price. In December 1826, Lundy published an article that referred to a Baltimore slave trader as a “demon” and a “monster in human-shape.”113 Shortly thereafter, the man attacked Lundy—he choked him and repeatedly kicked Lundy in the head.114 “I was assaulted and nearly killed,” Lundy said.115 Lundy’s assailant was charged with assault, and the jury returned a verdict of guilty; the judge imposed a fine of one dollar. After defending slavery and noting its importance to Maryland’s economy, the judge told Lundy, “If abusive language could ever be a justification for battery, this was that case.”116 Lundy realized those who challenged slavery had few protections; from that point forward he tempered his antislavery commentaries.

The two editors did agree that ending slavery would take time; Garrison, Lundy, and nearly all opponents of slavery supported a gradual approach and colonization. Even that point of agreement, however, soon changed. While in Baltimore, Garrison discovered Lundy’s extensive library of antislavery literature. Garrison read The Book and Slavery Irreconcilable, written by George Bourne in 1816. Bourne’s book, together with David Walker’s Appeal and a pamphlet written in 1824 by British abolitionist Elizabeth Heyrick, dramatically changed Garrison’s thinking about slavery.

George Bourne is regarded by some as the first man in America to call for the immediate emancipation of the slaves.117 In The Book and Slavery Irreconcilable, the “book” was the Bible, and Bourne equated slavery with sin. “A gradual emancipation is a virtual recognition of the right, and establishes the rectitude of the practice,” Bourne wrote. “If it be just for one moment, it is hallowed for ever; and if it be inequitable, not a day should it be tolerated.”118

In 1824 British writer Elizabeth Heyrick reached the same conclusion as Bourne, summed up in the title of her booklet, Immediate, Not Gradual Abolition. Heyrick wrote that delaying the end of slavery affirmed the institution and was the equivalent of doing nothing.119 “An immediate emancipation then, is the object to be aimed at,” Heyrick wrote. “It is more wise and rational, more politic and safe, as well as more just and humane, than gradual emancipation.”120 Benjamin Lundy promoted Heyrick’s pamphlet in his newspaper.121

In his Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World in 1829, David Walker called for the immediate end of slavery. Lundy condemned Walker’s book because of Walker’s willingness to embrace violence as a means of destroying slavery. Garrison, however, was less critical. “It is not for the American people, as a nation, to denounce it as bloody or monstrous,” Garrison said. Garrison reminded readers that colonists violently took up arms to shoot and kill the British and win a war of freedom. “Mr. Walker but pays them in their own coin, but follows their own creed, but adopts their own language. … If any people were ever justified in throwing off the yoke of their tyrants, the slaves are that people.”122 After reading Bourne, Heyrick, and Walker, Garrison embraced immediate emancipation and rejected the idea of colonization—sending free blacks and slaves back to Africa—as dangerous and wrong.

Garrison’s partnership with Lundy concluded after six months. In that time, the Genius of Universal Emancipation suffered serious financial losses as the result of a libel suit filed against Garrison. Garrison accused merchant Francis Todd of Newburyport of transporting slaves on ships that Todd owned. During the course of the trial, Garrison proved that Todd in fact transported slaves. It made no difference. In the slave state of Maryland, the jury quickly returned a verdict of guilty. The judge fined Garrison fifty dollars plus costs, bringing the total fine to seventy dollars, and sentenced him to six months in the Baltimore jail beginning on April 17, 1830.123 Lundy published Garrison’s report of his trial and imprisonment, and he visited Garrison at the jail every day.124

Garrison received many visitors, sent many letters, and wrote protests on the prison walls. “The tyranny of the court has triumphed over every principle of justice, and even over the law—and here I am in limbo,” Garrison said.125 He spoke with escaped slaves who were held at the jail and befriended the warden, who allowed him to dine with his family. “True it is, I am in prison, as snug as a robin in his cage; but I sing as often, and quite as well, as I did before my wings were clipped,” Garrison wrote.126

For Benjamin Lundy, Garrison’s imprisonment meant the end of the Genius of Universal Emancipation as a weekly newspaper. As a result of “scanty patronage” and threats of more lawsuits, Lundy announced plans to scale back to a monthly publication.127 Shortly thereafter, Lundy received a letter from New York businessman Arthur Tappan. “I have read the sketch of the trial of Mr. Garrison with that deep feeling of abhorrence of slavery,” Tappan wrote. “If one hundred dollars will give him his liberty, you are hereby authorized to draw on me for that sum, and I will gladly make a donation of the same amount to aid you and Mr. Garrison in re-establishing the Genius of Universal Emancipation.”128 With Tappan’s gift, Lundy paid Garrison’s fine, and the sympathetic warden assisted in his early release from prison. On June 5, 1830, Garrison walked out of the Baltimore Jail after serving forty-nine days of his six-month sentence.129

Despite Arthur Tappan’s hope that Lundy and Garrison would continue their partnership, their differences in style and approach convinced them to go separate ways. In a farewell to their readers, Lundy praised Garrison’s “strict integrity, amiable deportment, and virtuous conduct.” Garrison added, “We shall ever remain one in spirit and purpose.”130 Garrison had no regrets. “In all my writings I have used strong, indignant, vehement language, and direct, pointed, scorching reproof,” Garrison said. “I have nothing to recall.”131

While in jail, Garrison resolved to dedicate his life to the eradication of slavery. “Everyone who comes into the world should do something to repair its moral desolation, and to restore its pristine loveliness,” Garrison wrote. “He who does not assist, but slumbers away his life in idleness, defeats one great purpose of his creation.”132 On his release, Garrison began a lecture tour to raise money for a new newspaper.

City officials and leaders in Boston did not rejoice when Garrison returned to the city in 1830. He tried to reserve a hall in Boston for a speech, but everyone he contacted refused his request. As a last resort, he announced plans for a speech on the Boston Common. The prospect of a large and unruly gathering on the Common changed the minds of city leaders. They quickly issued an invitation for the free use of Julien Hall, and Garrison accepted.133

Boston’s abolitionist community turned out to hear Garrison on October 15, 1830. The audience included John Tappan, brother of Arthur Tappan; Moses Grant, a prominent local merchant in the paper business who was active in the temperance movement; attorney Samuel E. Sewall; and a number of ministers, including Lyman Beecher and Samuel Joseph May, a Unitarian minister from Brooklyn, Connecticut. Garrison discussed the “sinfulness of slave-holding” and “the duplicity of the Colonization Society.” He also said, “Immediate, unconditional emancipation is the right of every slave and the duty of every master.”134

Garrison’s speech had a powerful effect. “That is a providential man; he is a prophet; he will shake our nation to its center, but he will shake slavery out of it,” May said. “We ought to know him, we ought to help him.”135 May came from a prominent Boston family and had graduated from the Harvard Divinity School. He assisted at churches in Boston and New York City before accepting a call to a church in Brooklyn, Connecticut. Garrison, May, Amos Alcott, and Samuel Sewall gathered at Alcott’s home after the speech. “Mr. Garrison, I am not sure that I can indorse all you have said this evening,” May said. “Much of it requires careful consideration. But I am prepared to embrace you. I am sure you are called to a great work, and I mean to help you.”136

May recalled an incident from the summer of 1821, when he and his sister traveled from Washington, D.C., to Baltimore to visit friends and relatives. While riding in a public stagecoach, they saw a row of black men chained together in handcuffs walking behind a wagon, and young children in another wagon, lying on straw. “My first thought was that they were prisoners,” May said. “Scarcely had I uttered the words, when the truth flashed … They are slaves.”137 May recalled that another passenger, a southerner, noticed May’s reaction: “It is bad. It is shameful. But it was entailed upon us. What can we do?”138

May had agreed to preach at the Summer Street Church in Boston as a favor to a minister who was away and decided to change the focus of his sermon to slavery. “It is our prejudice against the color of these poor people that makes us consent to the tremendous wrongs they are suffering,” May said.139 He concluded with a dramatic call to either end slavery or break up the United States. “Tell me not that we are forbidden by the Constitution of our country to interfere in behalf of the enslaved. … If need be, the very foundations of our Republic must be broken up … It cannot stand, it ought not to stand, it will not stand, on the necks of millions of men. For God is just, and his justice will not sleep forever.”140

The congregation reacted with bewilderment and outrage that rippled through the rows of parishioners. May acknowledged the response at the end of the service, but did not apologize. “Everyone present must be conscious that the closing remarks of my sermon have caused an unusual emotion throughout the church,” May said. “I am glad. Would to God that a deeper emotion could be sent throughout our land.”141 A woman who approached May after the service told him, “Mr. May, I thank you. What a shame it is that I, who have been a constant attendant from my childhood in this or some other Christian church, am obliged to confess that today, for the first time, I have heard from the pulpit a plea for the oppressed, the enslaved millions in our land.”142

Not everyone who heard Garrison’s speech had the same positive reaction as Samuel May. Moses Grant, the paper merchant, rejected Garrison’s call for immediate emancipation and declined to help.143 John Tappan strongly supported colonization and told his brother Arthur it was a shame he had bailed Garrison out of jail.144

Gradually, Garrison enlisted the help of other friends and supporters. Isaac Knapp, a boyhood friend and the original owner of the Free Press, offered typesetting assistance. Stephen Foster, a colleague at one of the religious papers, the Christian Watchman, volunteered to print Garrison’s newspaper until he could afford a press of his own.145 With the publishing arrangements in place, the newspaper needed a memorable name. Samuel Sewall suggested the Safety Lamp.146 Garrison initially proposed to call it the Public Liberator and Journal of the Times.147 This became the Public Liberator, and finally, the Liberator. The Liberator became the most famous, influential, and longest running of any abolitionist newspaper.

In the fall of 1830, Garrison reached out to the black population of Boston for support and subscriptions. Many knew of Garrison’s brief partnership with Benjamin Lundy, his imprisonment in Baltimore, and his Independence Day speech regarding slavery. In the fall of 1830, the black community in Boston needed advocates. The black newspaper Freedom’s Journal had ceased publication in 1829. Black leader David Walker had died, most likely as a result of tuberculosis, although some believed he was poisoned and murdered. The lanky twenty-four-year-old Garrison begged the question—how could this young, white man know of the trials and needs of the black community? Garrison persisted, and in November and December of 1830, he received support at black churches and in meetings with black leaders. As one commentator later wrote, “It is no wonder that, after launching his operation without a single subscriber or a penny in reserve, with borrowed type and paper obtained on the shakiest of credit, he quickly picked up 450 subscribers, of whom 400 were Negroes.”148

Garrison published volume one, number one of the Liberator in Boston on New Year’s Day 1831. In the time since his Independence Day speech in 1829, he had witnessed slave auctions in the markets and streets of Baltimore. He had supported and then rejected colonization and its goal of returning blacks to Africa, an idea “full of timidity, injustice and absurdity.”149 Garrison took aim at both the slave owners in the South and slavery apologists in the North. Comparing his time in Baltimore with his years in Massachusetts, Garrison concluded that prejudice in the North was as bad and often worse than in the South. “I found contempt more bitter, opposition more active, detraction more relentless, prejudice more stubborn, and apathy more frozen, than among slave owners themselves,” Garrison said.150 “I determined, at every hazard, to lift up the standard of emancipation in the eyes of the nation, within the sight of Bunker Hill and in the birthplace of liberty.”151

While Garrison did not embrace violence, he aligned himself with the activist philosophy of David Walker. “Let all the enemies of the persecuted blacks tremble,” Garrison wrote in his passionate statement of purpose. “I will be as harsh as truth, and as uncompromising as justice. … I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—AND I WILL BE HEARD.”152

13. William Lloyd Garrison in the 1850s.

William Lloyd Garrison. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of I. N. Phelps Stokes, Edward S. Hawes, Alice Mary Hawes, and Marion Augusta Hawes, 1937 (37.14.37). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Garrison’s launch of the Liberator in January 1831, when he was twenty-five years old, was an act of faith. From a business point of view the entire enterprise, held together with borrowed assets and romantic notions, seemed doomed to failure. The cause of the newspaper—the immediate abolition of slavery—severely limited his base of subscribers and advertisers. This did not deter Garrison. “The curse of our age is, men love popularity better than truth, and expediency better than justice,” he wrote.153 The modest success he had achieved did not make him cautious. Instead, Garrison vowed to risk everything, his newspaper, what little money he had earned, his safety, his own freedom—everything—in a cause he knew was right.