Читать книгу Prudence Crandall’s Legacy - Donald E. Williams - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление6 : Sanctuary Denied

The ongoing acts of vandalism against Prudence Crandall’s school took a more serious turn in July 1833.

Almira Crandall managed the school as Prudence continued to recuperate from the sickness she suffered in the wake of her arrest. After a particularly long day, Almira sent the students to bed, paused to rest in the first-floor parlor room, and then went upstairs. Moments later a crash on the first floor resounded throughout the school. Almira rushed downstairs to investigate—an enormous impact had shattered the panes in the parlor window, and shards of broken glass covered the floor. Almira saw a rock in the middle of the floor “about the size of my hand and about an inch and a half in thickness.”1

The students came downstairs to see what happened; they were frightened but relieved that no one was hurt. Later that night Almira heard a loud thud of a rock hitting the clapboard wall of the schoolhouse. The following morning, Almira checked the outside of the school and noticed stains and dents from eggs and rocks that had smashed against the front of the school.2

An anonymous author published a fresh attack on Prudence Crandall in the Windham County Advertiser in July. “In her reckless disregard of the rights and feelings of all her neighbors, in her obstinate adherence to her plan of defiance of the entreaties of her friends and of the laws of the land, in her attempts to excite public sympathy by ridiculously spending a night in prison without the smallest necessity of it, she has stepped out of the hallowed precincts of female propriety … With all her complaints of persecution, I suspect she is pleased with the sudden notoriety she has gained.”3 The writer claimed he did not live in Canterbury and had no other interest in the school; however, the writer’s prose and point of view was consistent with that of Andrew Judson, the leader of the local colonization society.

“Let all things be done decently and in order,” the writer said. “If such an institution is to be established, let it be done with ultimate reference to the removal of the pupils to Africa. Here, and here only, can they stand on the proud eminence of freedom and equality.”4 Oliver Johnson was sufficiently impressed with the irony of the author’s assertion—true freedom and equality for blacks could exist only in Africa and not in the United States—that he reprinted the letter in its entirety in the Liberator.5

The vast majority of newspapers in Connecticut and elsewhere continued to express hostility toward Crandall and the abolitionists who supported her. The Norwich Courier called Crandall’s actions “very objectionable, and no friend we have met with can furnish any justification.”6 The editors of the Hartford Times accused Crandall’s supporters of “fraudulent misrepresentation” in their criticism of the Black Law and Crandall’s arrest.7 The Times took aim at “Tappan with his purse—Garrison with his insane projects—and zealots who are devoted to the welfare of Heathen abroad and Negroes and Indians at home.”8 Crandall and her abolitionist friends conspired to destroy the harmony of Canterbury, the Times said, “regardless of the feelings of those who happened to be white.”9 The New Hampshire Patriot described Crandall as a “fanatic old maid” who “knew what the law was but she wished to be considered a martyr.”10 The editors of the Patriot said Crandall was arrested “not exactly for teaching young negroes to read, but for breaking the law,”11 and called her night in jail “a mere make-believe imprisonment.”12 The editors of the New Haven Register agreed with Crandall’s opponents who said that town officials should be allowed to prohibit “a school of imported negroes … Should two or three mad persons have more power than the whole of the inhabitants of a town?”13

Samuel May wrote to Arthur Tappan to tell him of the new developments. He described the difficulties the school faced in the wake of Crandall’s imprisonment, including the increased vandalism and hostile press coverage. Despite the success of publicizing Crandall’s night in jail, May said “adversaries wielded several newspaper presses incessantly against Miss Crandall’s school, and the others would not venture to defend it.”14 The articles “teemed with the grossest misrepresentations, and the vilest insinuations against Miss Crandall, her pupils and her patrons,” and the newspapers refused to allow any space “to refute the slanders they were circulating.”15

May knew that Crandall needed additional allies and resources to respond to Judson and his campaign to close the school. May sent his letter to Tappan and made plans to travel to New York City. Four days later, on the morning of Thursday, July 11, 1833, without warning, Arthur Tappan appeared at May’s door in Brooklyn, Connecticut.16

“I never grasped a human hand with more joy or gratitude,” May said.17 Tappan left his pressing business matters in New York to see Crandall’s school for a firsthand look at the challenges she faced. Tappan’s visit came at a critical time. Prudence Crandall still had not regained her strength after months of fighting for the school’s survival. May increasingly worried about the school’s future in light of the passage of the Black Law and Crandall’s pending trial. He also questioned his own effectiveness given that his abolitionist views had strained relations with his friends and parish. “I found myself becoming an object of general distrust,” May wrote to Tappan, “and perceived that I was losing my hold upon the confidence of the few who had ventured to give me any support.”18 Once inside May’s home, Tappan told May he needed to better understand how he could help Crandall’s school.

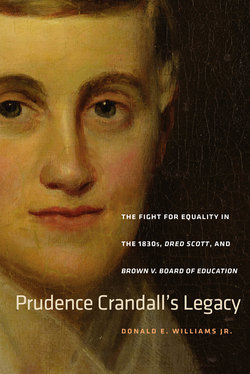

20. Arthur Tappan, a wealthy merchant and financial supporter of abolitionism and Prudence Crandall’s school.

Arthur Tappan. From Wendell Phillips Garrison and Francis Jackson Garrison, William Lloyd Garrison, 1805–1879: The Story of His Life Told by His Children, vol. 1 (New York: Century, 1885), 190.

“Your last letter implied that you were in so much trouble I thought it best to come and see,” Tappan told May, “and consider with you what it will be advisable for us to do.”19 May suggested that the drumbeat of attacks in the press contributed significantly to ongoing opposition in the community. The publisher of one of the local papers, who was a friend of May, told him that he could not possibly print an article in defense of Crandall’s school—it would result in the destruction of his readership and relations with advertisers.20 After listening to May, Tappan called for a carriage and set off to Canterbury to visit the school. He made the six-mile journey to the school without May; Tappan wanted to see Crandall’s school and its students on his own.

Prudence Crandall had met Arthur Tappan in New York City in February and subsequently had boasted to her neighbors about his support for her school. At the time she had no idea that her decision to educate young black women would place her in the center of a wrenching controversy leading to her arrest and imprisonment. When Tappan appeared at her door in July, she expressed surprise, disbelief, and gratitude. Tappan was as deeply moved, however, when he toured the school and experienced firsthand what Crandall had accomplished in the face of great adversity: the schoolhouse was filled to capacity with bright and eager young women receiving their lessons. Crandall had succeeded in establishing a thriving, ongoing school for black women. He listened carefully as Crandall spoke about the opposition to her school, her pending criminal trial, the ongoing vandalism and harassment, and the articles in the press that condemned the school.21 He stayed at the school for nearly three hours before returning to May’s home in Brooklyn.

“I believe I now fully understand ‘the bad predicament’ of which you wrote to me … It is even worse than I supposed,” Tappan told May.22 He told May that the fate of Crandall’s school could well influence the cause of the entire black population of the United States.23

“You must start a newspaper as soon as possible, that you may disabuse the public mind of the misrepresentations and falsehoods with which it has been filled,” Tappan said. “Get all the subscribers you can, and I will pay all the expenses you may incur more than the income you receive from subscribers and advertising patrons.”24 May wasted no time in accepting the offer. May told Tappan of a newspaper that had recently gone out of business, with offices and press equipment, in Brooklyn, Connecticut. “We must have it,” Tappan said. “Let us go immediately and secure it.”25

The printing office was a short distance from May’s house, so the two men walked to the building, located the man who controlled the dormant press, and settled on a one-year lease of the premises and equipment.26 On the walk back, May and Tappan talked about the need for immediate emancipation of the slaves and “the great conflict for liberty.”27 They agreed that the fight for liberty included the vigorous defense of Crandall’s school.

Shortly thereafter the stagecoach arrived to take Arthur Tappan back to New York City. May and Tappan exchanged commitments of support and mutual farewells. As the coach pulled away, May realized he had agreed to publish a yet-unnamed newspaper that would tell the truth about Crandall’s school, attack the unconstitutional Black Law, and refute scurrilous commentary from other newspapers. During the next year the expenses of the newspaper totaled more than six hundred dollars, a significant sum in 1833. Arthur Tappan paid all of it.28

Tappan’s unexpected visit cheered Prudence Crandall and Samuel May. When May awoke on Friday, July 12, however, he realized much work lay ahead. “A night’s rest brought me to my senses, and I clearly saw that I must have some other help than even Mr. Tappan’s pecuniary generosity could give me,” May said.29 At the time May published a religious paper, the Christian Monitor, served as pastor of the Unitarian Church in Brooklyn, and taught at Crandall’s school. Publishing and editing a weekly political newspaper in addition to his other responsibilities “was wholly beyond my power,” May said.30 May recently had read a thoughtful, well-written article in the Emancipator, reprinted from Benjamin Lundy’s The Genius of Universal Emancipation, criticizing Connecticut’s Black Law. Charles C. Burleigh wrote the article and lived in Plainfield, Connecticut, a short carriage ride from Brooklyn. May decided to go to Plainfield and find Burleigh.31

May arrived at the Burleigh family farm later that same day. The dry, sunny weather made it a perfect day for haying, and Charles and his brothers were all in the fields. Charles’s mother told May to come back another time, but May persisted. “My business with him is more important than haying,” May said.32

Charles Burleigh did not impress May at first. Burleigh came in from the fields in his ragged farm clothes. He had a scruffy beard. Twenty-two years old, Burleigh taught in the local district school and studied law while helping his parents tend to their farm. As May and Burleigh talked about the antislavery movement, however, May heard the voice of the writer who wrote the eloquent article in the Emancipator. May trusted his instincts and immediately offered the job of newspaper editor to Charles. When May promised to help find a person to take Burleigh’s place at the family farm, Charles accepted.33 Burleigh began his new career in publishing the very next Monday, July 15, 1833.

17. Charles C. Burleigh, editor of the Unionist. He favored immediate emancipation, equal rights for women, and repeal of the death penalty.

Charles C. Burleigh. From Wendell Phillips Garrison and Francis Jackson Garrison, William Lloyd Garrison, 1805–1879: The Story of His Life Told by His Children, vol. 3 (New York: Century, 1885), 226.