Читать книгу Prudence Crandall’s Legacy - Donald E. Williams - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4 : A Mountain of Prejudice

Andrew Judson immediately launched a campaign to publicize the outcome of the Canterbury town meeting and to attack Crandall’s school. In letters to the local newspapers he praised the civility of Crandall’s opponents and criticized Crandall’s “foreign” supporters, who Judson said tried to intimidate the citizens of Canterbury. By Judson’s own count there were just five supporters of Prudence Crandall at the Canterbury meeting.1 While there were many hundreds of citizens in attendance—and no one voted against the resolutions—Judson wrote that Crandall’s five supporters presented “an array of foreign power, bringing with it boasted foreign influence.”2 Their presence was “imposing” according to Judson, and they “took conspicuous posts” within the church.3 “Their talking, language, and note-taking became offensive, and necessarily disturbed the progress of the meeting.”4

Judson promoted the idea that outsiders had disrupted the town meeting. Another account, signed “A Friend of the Colonization Cause” and likely written by Judson, noted that foreigners, having “thrust themselves into (the) assembly of the freemen of Canterbury … soon began to disturb the meeting by whispering, laughing, and … taking notes, etc.”5 The odd objection to “taking notes” caught the attention of Samuel May, who replied in a published letter addressed to Judson. “Permit me to say sir, if you or some of your coadjutors had adopted the precaution of ‘taking notes’ at the time (for which precaution you seem to be offended at one of the Providence young men) you probably would have given as correct an account of the meeting as he has done in the Liberator, and not committed so many mistakes in your communications to the Norwich papers …”6

Judson also criticized the brief speeches by May and Buffum following the meeting. “Their language was so highly charged with threats,” Judson said, and their “conduct so reprehensible” that the trustees of the church had no choice but to demand that they cease and desist.7 Local newspapers printed Judson’s false characterization of the meeting and its aftermath.

On Monday, March 11, 1833, two days after the town meeting, Judson traveled to Brooklyn to see Samuel May. Judson told May he did not have any personal dislike for him and apologized for “certain epithets” Judson delivered in “the excitement of the public indignation of his neighbors.”8 May later wrote an extensive and verbatim account of his exchange with Judson.

May told Judson that that he was “ready, with Miss Crandall’s consent, to settle the difficulty” with Judson and the people of Canterbury peaceably.9 May said that Crandall would agree to move her school to another location in Canterbury if she could recover what she paid for the house. Judson rejected any such compromise.

“Mr. May, we are not merely opposed to the establishment of that school in Canterbury,” Judson said. “We mean there shall not be such a school set up anywhere in our state. The colored people never can rise from their menial condition in our country … They are an inferior race of beings, and never can or ought to be recognized as the equals of the whites. Africa is the place for them. … The sooner you Abolitionists abandon your project the better for our country, for the niggers, and yourselves.”10

May told Judson that the United States must recognize the rights God gave to all men. “Education is one of the primal, fundamental rights of all the children of men,” May said. “If you and your neighbors in Canterbury had quietly consented that Sarah Harris, whom you knew to be a bright, good girl, should enjoy the privilege she so eagerly sought, this momentous conflict would not have arisen in your village.”11

They continued their private debate. Judson said if the old vagrancy law was insufficient to block students from coming into the town, “then we will get a law passed by our Legislature, now in session, forbidding the institution of such a school as Miss Crandall proposes, in any part of Connecticut.”12 May said Crandall’s supporters would challenge such a law “up to the highest court of the United States.”13

Judson’s visit with May did not result in a reconciling of their respective views. “Mr. Judson left me in high displeasure,” May wrote. “I never met him afterwards but as an opponent.”14 Three days later on Thursday, March 14, 1833, eleven men arrived at Prudence Crandall’s home to present her with the resolutions passed at the town meeting. This time, Crandall did not face the committee alone—her father Pardon and sister Almira were with her when the men arrived.15 Samuel Hough, the owner of an axe factory and the man who had loaned Crandall some of the money she needed to purchase the schoolhouse, read the resolutions to Crandall and her family.16 The visit was an anticlimax to the hostility at the town meeting. The resolutions stated what was already well known; many in town were fearful of the proposed school and hoped Crandall would abandon her plan. There was no requirement for her to do or refrain from doing anything. Crandall resumed preparing the schoolhouse for the new students.

The war of words continued. The next issue of the Liberator appeared on March 16 and included Henry Benson’s account of the Canterbury town meeting. William Lloyd Garrison set the names of five prominent opponents to Crandall’s school—Andrew Judson, Rufus Adams, Solomon Paine, Richard Fenner, and Andrew Harris—in large, bold letters below the banner headline, “Heathenism Outdone.” Garrison called them “shameless enemies of their species” and said their disgraceful behavior “will attach to them as long as there exists any recollection of the wrongs of the colored race.”17 Six days later, on Friday, March 22, Judson and his supporters released a lengthy attack on Crandall’s school titled “Appeal to the American Colonization Society.” Excerpts from Judson’s letter were printed in a number of publications, including the Norwich Republican. “In their wild career of reform,” Judson said, referring to Garrison and the abolitionists, “those gentlemen would justify intermarriages with the white people!!”18

Judson submitted a longer draft of his letter to the North American Magazine and took additional jabs at Garrison and his quest for emancipation. “What right has William Lloyd Garrison to tell us that we are slumbering in moral death, and that he and his immediate associates first made the attempt to arouse us?” Judson asked. “Before Garrison was born, there existed in the public mind as deep an abhorrence of slavery, as he can excite with his tongue or his pen. But New England well knows, that by the Constitutional terms of our national compact, she has no more right to interfere with the internal domestic policy of the Southern states, than with the concerns of a foreign power. … Talk of immediate abolition! You might as safely open the gates of a menagerie, and permit its savage tenants to roam among the haunts of men, as at once to emancipate the slaves. Talk of forcing the South to abolish slavery! You might as well think of uprooting the Allegheny Mountains from their deep foundations.”19

Many in the North viewed slavery as a necessary evil permitted by the Constitution and required to support the economy of the South. Judson shared Thomas Jefferson’s views regarding slavery in some respects; Judson believed that slavery would disappear at some ill-defined point in the future, perhaps through colonization and sending blacks back to Africa. “Southern prejudice in relation to slavery, is like the oak,” said Judson. “But by calm rational effort, I doubt not, but that the axe may be laid at the root in due time, and this towering tree will come to the ground.”20

As Judson intensified his campaign in favor of colonization and against Crandall’s school, Arthur and Lewis Tappan moved to cut their last ties to the colonization movement. When the American Colonization Society became popular in the 1820s, the Tappan brothers had supported the effort to send blacks to Liberia. Lewis Tappan helped organize the Massachusetts Colonization Society in 1822.21 Arthur Tappan joined the American Colonization Society in 1827, and he served as vice president of the African Education Society, a subcommittee of the Colonization Society.22 Arthur and Lewis Tappan also had a financial interest in the colonization movement; the Tappans secured potentially lucrative contracts for exports and shipping between Liberia and the United States.23

The Tappan brothers left the Colonization Society in 1831. The shipping business that the Tappans expected from Liberia never materialized, and their business contact in Liberia died of fever.24 Arthur Tappan did not criticize the colonization movement publicly at that time, as many of his friends and customers continued to support colonization. Two years later, however, Tappan decided to publicly denounce colonization when the Anti-Slavery Society of Andover, Massachusetts, asked him whether colonization “is worthy of the patronage of the Christian public?”25 In his letter of March 26, 1833, he admitted he was once one of colonization’s warmest friends, but now believed that colonization would “deepen the prejudice against the free colored people” and strengthen slavery.26

“It had its origin in the single motive to get rid of the free colored people, that the slaves may be held in greater safety,” Tappan wrote. “Good men have been drawn into it under the delusive idea that it would break the chains of slavery and evangelize Africa; but the day is not far distant, I believe, when the society will be regarded in its true character, and be deserted by everyone who wishes to see a speedy end put to slavery in this land of boasted freedom.”27 Garrison published Tappan’s letter in the Liberator on April 6, 1833.

Tappan’s shift away from colonization represented an important turning point for antislavery activists in New York City and elsewhere. Tappan held many progressive views, but most regarded him as a moderate compared to abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison. Tappan helped promote Garrison’s call for immediate emancipation to a broader audience. Throughout the 1830s, many opponents of slavery followed the example of the Tappan brothers and withdrew their support for colonization.28

Prudence Crandall prepared for the opening of her school for black women, scheduled for Monday, April 1, 1833. George Benson stopped by the school to assist Crandall. “I have just returned from Canterbury and Brooklyn, where all is commotion,” Benson reported to William Lloyd Garrison. “The cause of the oppressed will be maintained, the school will go into operation next week, and I trust will be nobly supported.”29

Andrew Judson and his allies realized the resolutions they had passed at the March 9 town meeting had accomplished nothing. Judson scheduled another town meeting specifically to call on the state legislature to close Crandall’s school. On the evening of April 1, townspeople gathered at the Congregational Church to vote on a new resolution. The meeting had none of the tension and drama of the first town meeting. The rhetoric of the resolution, however, was more pointed and alarmist. It claimed the school was in fact not a school at all, but rather a theater from which the abolitionists would “promulgate their disgusting doctrines of amalgamation and their pernicious sentiments of subverting the Union.”30 The resolution stated that Crandall’s school, under the false pretense of educating black women, would instead “scatter firebrands, arrows and death among brethren of their own blood.”31 After some discussion the townspeople “voted that a petition in behalf of the town of Canterbury to the next General Assembly be drawn up in suitable language, deprecating the evil consequences of bringing from other towns and other states people of color for any purpose. …”32 Judson also attempted to outlaw criticism of the colonization movement. The resolution called on the legislature to prohibit schools from “disseminating the principles and doctrines opposed to the Benevolent Colonization System.”33 Finally, the resolution requested that the legislature enact such laws as necessary to put an end to the “evil” of Crandall’s school.34 The resolution once again established a committee, which included Andrew Judson, for the purpose drafting a petition to the general assembly and encouraging other towns to send similar petitions to the legislature.

The town meeting vote provided Andrew Judson, who served in the state legislature, with a directive to craft legislation to close Crandall’s school. In addition, since the resolution encouraged other towns to petition the legislature for similar relief, Judson began the work of building a coalition of support in the legislature. He knew his legislation stood a better chance of passage if other towns supported and promoted the same cause. Judson organized petition drives throughout the state.

The debate in the press concerning colonization and Prudence Crandall’s school continued to escalate. Samuel May published two lengthy responses to Judson’s comments. In reply to Judson’s statement that ending slavery was akin to uprooting the Allegheny Mountains, May said he would rather tear down the mountains than transport 2.5 million blacks to “the wilds of Africa” as the supporters of colonization had proposed.35 May said he renounced colonization because it perpetuated the “degradation of our colored brethren” and was not committed to equality or emancipation.36 May said both he and Prudence Crandall favored immediate emancipation: “We do so from the deep conviction that few if any sins can be more heinous than holding fellow men in bondage and degradation.”37

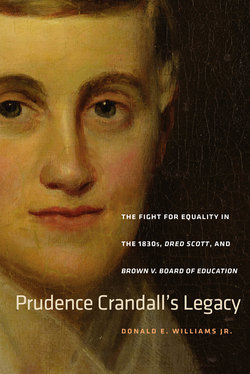

16. Samuel Joseph May, a minister, teacher at Prudence Crandall’s school, and devoted friend to Crandall and Garrison.

Samuel Joseph May. From Wendell Phillips Garrison and Francis Jackson Garrison, William Lloyd Garrison, 1805–1879: The Story of His Life Told by His Children, vol. 1 (New York: Century, 1885), 466.

May also addressed the more sensational charge that Crandall’s school promoted marriage and “amalgamation” between blacks and whites. He noted the allegations regularly were “repeated in the Norwich papers” and “harped upon at the town meeting by the opposers of Miss Crandall.”38 May said Judson’s claim was false and simply a tactic to “shock the prejudices of the people, and dupe their judgment.”39

While May wrote that the purpose of Crandall’s school was wholly unrelated to interracial marriage, he did not recoil from the idea, even in his public response to Judson. “Of course we do not believe there are any barriers established by God between the two races,” May wrote. “Whether marriages shall or shall not take place between those of different colors is a matter which time must be left to decide. … We only say that such connections would be incomparably more honorable to the whites as well as more consistent with the laws of God and the virtue of our nation than the illicit intercourse which is now common especially at the south.”40 May published his letters in the local newspapers and paid a print shop to assemble them into a pamphlet and distribute it throughout the region.

Prudence Crandall heard rumors that Andrew Judson had prepared a libel lawsuit against William Lloyd Garrison for statements Garrison made in the Liberator, specifically in his article “Heathenism Outdone.”41 Garrison cared little about whether his comments offended anyone. The harshness of some of Garrison’s articles, however, surprised Crandall, and she asked Garrison to restrain his attacks. “Handle the prejudices of the people of Canterbury with all the mildness possible,” she wrote to Garrison, “as everything severe tends merely to heighten the flame of malignity amongst them.”42 While Samuel May respected and loved Garrison’s “fervent devotion to the cause of the oppressed,” he wrote that “no one can disapprove, more than I do, the harshness of his epithets, and the bitterness of his invectives.”43

The pleas of May and Crandall may have resulted in a moment of reflection for Garrison, but in the end he refused to moderate his attacks on those who supported or tolerated slavery and prejudice. “It is a waste of politeness to be courteous to the devil, and to think of beating down his strongholds with straws is sheer insanity,” Garrison wrote in the Liberator. “The language of reform is always severe, unavoidably severe.”44 Garrison had faced lawsuits, death threats, and time in jail. The rumor of Andrew Judson’s libel suit did not intimidate him, at least not initially.

Garrison’s inflammatory language had a more direct and personal consequence for Crandall and her supporters in Canterbury. Garrison could level his charges and print his attacks from the relative safety of his office in Boston. He had the support of a larger abolitionist community, both black and white. Crandall greatly appreciated Garrison’s strong support and moral clarity, but she faced the daily anger of the Canterbury townspeople he criticized. When consequences ensued from Garrison’s attacks in the Liberator, they fell on Crandall, her students, and her school.

It did not take long for Crandall’s opponents to launch their next offensive. At an informal meeting at the Canterbury Masonic Hall on Friday, April 5, 1833, town leaders and businessmen agreed to cut off Prudence Crandall and her family from the Canterbury community to the greatest extent possible. Merchants agreed not to sell her anything or assist her in any way.45 At least one merchant refused to go along with the planned embargo. Stephen Coit opposed Crandall’s school for black women but said he intended to sell his goods to anyone who wished to buy them, including Crandall.46 Coit’s daughters, Frances and Sarah, had attended Crandall’s school prior to Sarah Harris’s enrollment.47

The organized embargo—a tactic associated with war—sent a message to townspeople that they need not behave in a civilized manner toward Crandall or her supporters. The campaign succeeded in ostracizing Crandall and worsened relations with her neighbors. Taunts, threats, and vandalism directed against Crandall increased and went unpunished. In a letter written at the beginning of April to her friend in New Haven, Simeon S. Jocelyn, Crandall said she was “surrounded by those whose enmity and bitterness of feeling can hardly be contemplated.”48

The official opening of her new school, a “high school for young colored ladies and misses,” occurred as planned on April 1, 1833. Crandall hoped to have fifteen to twenty students. Instead, only two students, Eliza Glasko from Griswold and Sarah Harris, arrived on the first day.49 Crandall remained concerned about Judson’s efforts to close her school; however, she knew that an inability to enroll enough students to meet her basic expenses was the surest path to failure. “I have but one boarder yet and one day scholar,” she wrote to Jocelyn. “I wish you to encourage those who are coming to come immediately.”50

The Canterbury controversy did not prevent Garrison from proceeding with his plans to travel to England. While in England, he intended to raise money for the Liberator and speak out against colonization. “There, I shall breathe freely—there my sentiments and language on the subject of slavery will receive the acclamations of the people—there my spirit will be elevated and strengthened,” Garrison said.51 In March he asked George Bourne to serve as guest editor of the Liberator while he was away.52

Garrison met Bourne on a trip to New York a few years earlier, and they became colleagues and collaborators.53 Bourne’s historic antislavery tract, The Book and Slavery Irreconcilable, provided intellectual guidance for Garrison when he launched the Liberator.54 Garrison enlisted Bourne to serve as a reference for Prudence Crandall’s school, and Bourne’s name appeared as one of the supporters of the school in the advertisements for the school in the Liberator. Bourne agreed to edit the newspaper each week in New York City while Garrison was away and write the strident, antislavery articles that Garrison’s readers expected. In addition, Bourne agreed to write a weekly, anonymous column called “The Firebrand,” write one or two other articles of his choosing, and contribute a full-length editorial each week. Bourne specifically told Garrison that he did not want an announcement that he was filling Garrison’s shoes in any capacity.55 Isaac Knapp, Garrison’s assistant, and Oliver Johnson, a frequent guest editor and fellow abolitionist, agreed to assemble and print the newspaper in Boston.

Garrison traveled to Haverhill, Massachusetts, on Saturday, March 30, to meet with writer and poet John Greenleaf Whittier; Garrison was the first to publish Whittier’s poetry in the Newburyport Free Press in 1826. Garrison hoped to convince Whittier to write for the abolitionist cause. In addition, he wanted to meet three young women who called themselves the “Inquirers after Truth.” Harriet Minot and two female classmates wrote to him in support of his work in the Liberator and asked what, if anything, they could do to help end slavery. Harriet Minot was eighteen years old, Harriot Plummer was twenty, and Elizabeth Parrott was sixteen. Their letters intrigued Garrison.

“A thought has just occurred to me,” Garrison wrote to Minot in March. “Suppose I should visit Haverhill previous to my departure for England: is it probable that I could obtain a meeting-house in which to address the inhabitants on the subject of slavery? … If I can be sure of a house, I will try to come Sabbath after next.”56 Garrison told Minot he also wanted to visit John Greenleaf Whittier. A week later, however, Garrison had not secured a hall for his speech nor had he contacted Whittier to arrange a meeting. He wrote to Minot, “I shall visit your beautiful village on Saturday next even should no arrangements be made for the delivery of an address.”57

As his sons later wrote in Garrison’s biography, the letters from Minot and her friends likely kindled romantic notions.58 His sons even speculated that when Garrison wrote, “We declare that our heart is neither affected by, nor pledged to, any lady, black or white, bond or free,” in the March 16 issue of the Liberator, he intended to send a message to these young female correspondents as to his own eligibility.59 Although Garrison was usually shy in matters of romance, on a number of occasions he did send thinly veiled love notes to young women through the newspaper when he worked in Newburyport and Bennington.60

While in Haverhill, Garrison did contact and meet with John Greenleaf Whittier, who agreed to join the abolitionist cause. Garrison also met the three “Inquirers after Truth” and was captivated by Harriet Minot. He wrote promptly to her after his visit and told her how much he enjoyed Haverhill, where “my spirit was as elastic as the breeze, and like the lark, soared steadily upward to the gate of heaven.”61 Garrison told her that Haverhill “has almost stolen my heart. Already do I sigh at the separation, like a faithful lover absent from the mistress of his affections. Must months elapse ere I again behold it? The thought is grievous.”62 Garrison’s not so thinly veiled interest in Minot resulted in friendship rather than romance, however. Garrison and Harriet Minot remained correspondents and friends throughout Garrison’s lifetime.

After visiting Haverhill, Garrison embarked on a speaking tour of various cities in the Northeast to raise money for his trip to England. He gave a farewell address before a black audience in Boston on Tuesday, April 2, and traveled to Providence for a similar address on Friday. At the Providence event the local Female Literary Society and the Mutual Relief Society raised fifty-five dollars for Garrison.63

The Benson family attended Garrison’s Providence speech. George Benson and his brother Henry lived in Providence, while the rest of the family—mother Sarah, father George, and sisters Mary, Sarah, Anna, and Helen—traveled from Brooklyn, Connecticut. They witnessed a passionate performance by Garrison and a fervent response by the crowd that took even Garrison by surprise. Many in the black congregation wept and surged around him at the conclusion of his remarks, and they reached out to touch him and shake his hand.64 After the Providence speech Garrison wrote, “The separation of friends, especially if it is to be a long and hazardous one, is a painful event indeed.”65

Garrison and the Bensons stayed overnight in Providence. The following morning, Garrison went to George Benson’s Providence store, where he met briefly with George and his sister Helen. George talked Garrison into traveling to Brooklyn, Connecticut, that afternoon and invited him to stay at the Benson home they called “Friendship Valley.” Once in Brooklyn, Samuel May—who lived across the street—came by to visit and provided Garrison with the latest news regarding Crandall’s school. May also invited Garrison to address his congregation at the Unitarian Meeting House the following day on Sunday, April 7, 1833.66 Garrison hesitated. He had not planned on speaking in Brooklyn. Garrison suspected that as a supporter of Prudence Crandall and editor of the Liberator, the Brooklyn parishioners would regard him as “a terrible monster.”67 Garrison rarely turned down speaking engagements, however, and he did not disappoint Samuel May.

Word reached Prudence Crandall that Garrison planned to speak on Sunday, and she and her sister Almira traveled to the meetinghouse to hear Garrison’s promotion of immediate emancipation.68 When the service began, Crandall noticed that every seat in the church was filled. Nothing Garrison said shocked or startled the congregation; Rev. May had discussed many of Garrison’s ideas in his own sermons. When Garrison finished his speech, the parishioners did not weep as they had in Providence, nor did they rush the podium to shake his hand. Crandall and her sister noted, rather, that the congregation seemed supportive of his remarks. Garrison later said, “As far as I could learn, the address made a salutary impression.”69 In a letter to his brother Henry, George Benson optimistically concluded that Garrison’s speech “removed a mountain of prejudice.”70

10. Unitarian Church of Brooklyn, Connecticut—Samuel Joseph May’s church.

Unitarian Church of Brooklyn, Connecticut. Library of Congress.

After the service, Prudence and Almira spent the evening with Garrison at the Benson’s home. Crandall and Garrison caught up on all of the news of the school, including details about the efforts of her opponents and how only two black women students had enrolled. Garrison assured her he would do all he could to boost enrollment.

“She is a wonderful woman, as undaunted as if she had the whole world on her side,” Garrison wrote to his partner at the Liberator, Isaac Knapp. “She has opened her school, and is resolved to persevere. I wish brother Johnson (Oliver Johnson) to state this fact, particularly, in the next Liberator, and urge all those who intend to send their children thither, to do so without delay.”71

Crandall’s evening with Garrison left her renewed and optimistic. “Indeed it was a source of great joy,” she wrote to Simeon S. Jocelyn.72 She stayed that night at the Benson home in Brooklyn and was able to see Garrison off to his next stop in Hartford. His departure did not occur as planned. The stagecoach for Hartford passed by the Benson home without stopping. Nearly an hour elapsed before the Bensons realized no other stagecoach for Hartford would travel through Brooklyn that day. Rather than have Garrison spend another evening in Brooklyn and miss his appointments in Hartford, George Benson decided to drive Garrison in his own wagon. Traveling in a severe rainstorm, Benson and Garrison eventually caught up to the stagecoach, but not before both were soaked and covered with mud. Garrison arrived in Hartford late Monday evening and addressed a congregation at a black church on Tuesday.73

Thirty minutes after Garrison left the Benson home in the pouring rain, a sheriff from Canterbury arrived at Friendship Valley looking for Garrison. He meant to serve Garrison with papers concerning Andrew Judson’s lawsuit for libel and require that Garrison appear in court. The Bensons said they did not know of Garrison’s whereabouts; the sheriff rode westward on horseback in an unsuccessful attempt to catch Garrison. Crandall believed the sheriff wanted to arrest Garrison and take him into custody. “It was also hinted that they wished to carry him to the South,” Crandall said. “This indeed was the occasion of much sorrow.”74

After speaking in Hartford, Garrison traveled by stagecoach to New Haven on Wednesday, April 10. When the coach stopped in Middletown, he met with Jehiel Beman, a minister in the abolitionist movement and one of Prudence Crandall’s supporters. “It was with as much difficulty as reluctance I tore myself from their company,” Garrison said of his visit with Beman and his black parishioners.75 On arriving in New Haven, Garrison was disappointed to find that his friend Simeon S. Jocelyn was away in New York City. Garrison allowed Simeon’s brother Nathaniel to paint an oil portrait of him; the Jocelyn brothers wanted a likeness suitable for engraving and reproducing in the abolitionist press while Garrison was away in England. On Friday, Garrison traveled to New York to meet Simeon S. Jocelyn, who told Garrison of his close escape from the Canterbury sheriff.76 “I was immediately told that the enemies of the abolition cause had formed a conspiracy to seize my body by legal writs on some false pretenses, with the sole intention to convey me south, and deliver me up to the authorities of Georgia—or in other words, to abduct and destroy me,” Garrison said.77 “No doubt the colonization party will resort to some base measures to prevent, if possible, my departure for England.”78

In a letter to Harriet Minot, Garrison described the “murderous design” of those who were trying to abduct him, the diversionary tactics necessary to avoid them, and his friends who were “full of apprehension and disquietude” on his behalf.79 “But I cannot know fear,” he told Minot. “I feel that it is impossible for danger to awe me. I tremble at nothing but my own delinquencies.”80 While Garrison enjoyed describing if not exaggerating the danger he faced for Minot’s benefit, Garrison had real reason for concern. Andrew Judson was not his only pursuer. Joshua N. Danforth, the New England agent for the American Colonization Society, noted in a speech in February that a person from one of the southern states had offered Danforth ten thousand dollars for the capture and delivery of Garrison.81 Danforth did not accept the offer, but he acknowledged on March 28, 1833, that Garrison “is, in fact, this moment, in danger of being surrendered to the civil authorities of someone of the southern states.”82

On the same day that Garrison met Simeon S. Jocelyn in New York City—Friday, April 12, 1833—Prudence Crandall received a third student at her school, Ann Eliza Hammond. Ann was from Rhode Island, and she joined Crandall as a boarding student. Crandall had met Hammond and her mother in February when she traveled to Providence.

Ann Eliza Hammond’s enrollment as the first black student from another state spurred Crandall’s opponents to quickly test the old vagrancy law. The law allowed town leaders to declare that a person from another state was a burden to the town and order the person to leave or risk paying a fine. Upon failure to pay the fine within ten days, the person would face either immediate expulsion or severe punishment—“he or she should be whipped on the naked body.”83

On Saturday evening, one day after Hammond arrived, Canterbury officials notified Prudence Crandall that they regarded Miss Hammond as a burden to the town. On Sunday, Crandall traveled to Brooklyn to tell Samuel May that she expected the town to serve a writ upon her as the guardian of Miss Hammond and require that she pay the fines.84 “I presume I shall be subjected to that penalty next Friday,” Crandall said. “I think it is best to pay the first fine when demanded. …”85 May told the treasurer of Canterbury that he and the Benson family were willing to post a bond in the amount of ten thousand dollars to protect the town from the cost of any vagrancy on account of students from other states.86

“A written offer of bonds has been presented to the selectmen by Mr. May to secure the town against any damage that shall be done by any of my pupils,” Crandall wrote to Simeon S. Jocelyn. “I presume the bonds will not be accepted by them—this is a day of trial.”87 The unexpectedly small enrollment combined with the ongoing opposition to her school depressed Crandall. “Disappointment seems yet to be my lot,” she wrote on April 17.88 “Very true, I thought many of the high-minded worldly men would oppose the plan, but that Christians would act so unwisely and conduct in a manner so outrageously was a thought distant from my view,” Crandall said. “If this school is crushed by inhuman laws, another I suppose cannot be obtained, certainly one for white scholars can never be taught by me.”89

On Saturday, April 20, Crandall discussed the vagrancy issue with Rev. May, who told her she should not pay any fine. Instead, May said she should take the matter to court. Crandall favored paying the fine and avoiding a legal confrontation, but she told May she would consider challenging the ordinance in court. May also told Crandall he received a letter from a friend in Reading, Massachusetts, inviting Crandall to move her school for black women to their town. Crandall wrote to Simeon S. Jocelyn and asked what he thought of moving her school to Reading, but stressed, “Do not mention this to anyone until we get further information from that town.”90 Crandall was willing to relocate her school but did not want to be misled. She thought Jocelyn would understand and have good advice; he had once believed the people of New Haven would embrace a college for black men.

The sheriff of Windham County served a legal writ upon Ann Eliza Hammond at Crandall’s school on Monday, April 22, 1833. The writ demanded that Hammond appear before attorney George Middleton, a justice of the peace, at the home of Chauncey Bacon on Thursday, May 2, at one o’clock in the afternoon, to answer charges brought by the town. Middleton could order Hammond to pay a fine of $1.67 for the previous week and command her to leave the town or face further fines. The writ also clearly stated that if Hammond refused to pay the fine and refused to leave, she would be “whipped on the naked body not exceeding ten stripes.”91 Word of the sheriff’s visit to the school traveled quickly to Brooklyn and Samuel May.

“I feared they would be intimidated by the actual appearance of the constable, and the imposition of a writ,” May said. “So, on hearing of the above transaction, I went down to Canterbury to explain the matter if necessary; to assure Miss Hammond that the persecutors would hardly dare proceed to such an extremity.”92 May told both Hammond and Crandall that they must not give in to the authorities, that no fines should be paid, and that Hammond must not leave Canterbury. He said that while the possibility of the town carrying out the ultimate punishment in the ordinance—a public whipping—was remote, May advised Hammond to submit to that fate “if they should in their madness inflict it.”93 Sixteen-year-old Ann Eliza Hammond had arrived in Canterbury only a week earlier to enroll in Prudence Crandall’s school. Now a minister from Brooklyn asked Hammond “to bear meekly the punishment” of a public whipping in order to expose their opponents as barbarians. “Every blow they should strike her would resound throughout the land, if not over the whole civilized world,” May said.94 May saw the controversy not only in terms of personal suffering, but also as part of a larger campaign to advance the cause of emancipation. Hammond accepted May’s challenge. “I found her ready for the emergency,” May said, “animated by the spirit of a martyr.”95

Andrew Judson traveled to New York City at the end of April. The purpose of his trip was likely to assist in efforts to capture Garrison. The colonization movement was very popular in New York, and Judson knew he could depend on assistance from those who were offended by Garrison’s attacks on colonization. There were at least two options if Judson succeeded in capturing Garrison: return Garrison to Canterbury to face libel charges, or hand him over to those from the South who hated Garrison and the Liberator. Crandall and her sister Almira worried about Garrison’s safety. “I hope that our friend Garrison will be enabled to escape the fury of his pursuers,” Almira Crandall wrote to Henry Benson. “Our anxieties for him were very great at the time Judson went to New York, as we expected his business was to take Mr. Garrison.”96

Eager to escape to England, Garrison left New York for Philadelphia hoping to board a boat bound for Liverpool, but he arrived too late—the ship had already set sail. Arthur Tappan persuaded Garrison to allow Tappan’s friend Robert Purvis to drive him by horse-drawn carriage to Trenton, New Jersey. While traveling along the Delaware River, Garrison barely escaped a fatal accident.97 A passing steamboat caught Garrison’s attention, and he wanted to see it from a point closer than the road. Purvis accordingly steered the carriage off the road and toward the river. After nearing the edge of a cliff, Purvis turned the carriage back toward the road and stopped. For a few minutes Garrison had an unobstructed view of the steamboat. After the boat passed by, Purvis took the reins and signaled for the horse to pull forward toward the road. Instead, the horse began to back up, moving the carriage closer to the cliff with each step. Realizing the danger and unable to stop the horse, Purvis jumped out of the carriage, expecting Garrison to do the same. Garrison did not move. Purvis shouted, “Sir, if you do not get out instantly, you will be killed.” Garrison finally jumped out the door, just as the horse abruptly stopped with the rear wheel of the carriage precariously balanced on the edge of the cliff.98

From Trenton, Garrison returned to New York City and traveled on to New Haven, where he continued to elude his enemies. He spent a few days with Nathaniel Jocelyn, who finished Garrison’s portrait. Nathaniel’s concern for Garrison’s safety was so great that he painted Garrison not in his studio, but in a room next to the studio and near a side exit, in case Garrison needed to flee.99 As for the portrait, Garrison deemed it a success and called it “a good likeness of the madman Garrison.”100

Garrison traveled once more to New York City, hoping to evade his potential kidnappers and depart for Great Britain. “I was watched and hunted, day after day in that city, in order that the writ might be served upon me,” Garrison said. “My old friend Arthur Tappan took me into an upper chamber in the house of a friend, where I was safely kept under lock and key, until the vessel sailed which conveyed me to England.”101

On the morning of May 1, Garrison made his way to the harbor and the ship Hibernia, bound for Liverpool. No one recognized or stopped him as he entered the boarding ramp. While the ship was still at anchor in the Port of New York, Garrison wrote again to Harriet Minot. “I have been journeying from place to place, rather for the purpose of defeating my enemies than from choice,” Garrison said. “I do not now regret the detention, as it enabled the artist at New Haven to complete my portrait … To be sure, those who imagine that I am a monster on seeing it will doubt or deny its accuracy, seeing no horns about the head.”102

Two and a half hours after the Hibernia sailed out of New York, someone representing a law office in Canterbury, Connecticut, made an inquiry about Garrison along the docks of the New York harbor.103 It was too late. Garrison was finally safe and away on his trip to England.