Читать книгу Prudence Crandall’s Legacy - Donald E. Williams - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5 : The Black Law

As the month of April ended, Prudence Crandall had only three black students at her school. In addition to local opposition, Crandall now battled a dire fiscal situation and realized she could not rely on advertisements in the Liberator to increase enrollment. When she received a letter from Arthur Tappan encouraging her to keep her school open, Crandall saw an opportunity.1 She traveled to Norwich on Monday, April 22, 1833, and boarded a ferry for New York City.

Crandall also made a decision concerning Ann Eliza Hammond and the vagrancy charge. While she appreciated the advice of Rev. May to stand firm and persuade Miss Hammond to submit to a whipping if necessary, Crandall did not agree. Crandall could not allow a child in her care to face even the remote possibility of brutal punishment at the hands of the town. With the deadline of the May 2 hearing fast approaching, Crandall paid the fine and ended the matter for the time being.2

The bitter opposition to the school took a toll on Crandall’s family, particularly her father. Pardon Crandall did not enjoy public attention and wanted to see the controversy brought to an end. “I have advised her often to give up her school and sell her property, and relieve Canterbury from their imagined destruction,” Pardon wrote. “Not that I thought she had committed a crime or had done anything which she had not a perfect right to do. But I wanted peace and quietness.”3

While Pardon privately encouraged his daughter to abandon her plans to educate black women, he stood by her when others criticized her school. Andrew Judson’s attacks in the press moved Pardon to respond. He sent a letter to Judson and Chester Lyon; Lyon was the assessor, sheriff, and judge of probate for Canterbury.4 Pardon included his letter in a pamphlet titled Fruits of Colonization, which combined letters and editorials critical of Judson and other opponents of Crandall’s school.

“The spirit of a father that waketh for the daughter is roused,” Pardon wrote. “I know the consequence. I now come forward to oppose tyranny with my property at stake, my life in my hand.”5 Pardon described how a gang of men came to his house and threatened to destroy his daughter’s schoolhouse unless she closed her school. The men also threatened to attack Pardon’s farm and demanded that he leave Canterbury. “It will be easy to raise a mob and tear down your house,” they said.6

The following day Pardon visited Andrew Judson and accused him of leading the “ungenerous and unrighteous conduct that has been pursued towards my daughter Prudence Crandall.”7 Judson responded with the threat of a lawsuit. “I had rather sue you than to sue her,” Judson told Pardon.8 Pardon said that a lawsuit seemed unnecessary given Judson’s plans to “pass a law that will destroy the school without a series of litigations.”9

Crandall’s impulsive trip to New York City, where she implored Arthur Tappan and the black ministers who supported her school to immediately secure students, resulted in success. By early May 1833, six students arrived from New York City. Shortly thereafter, enrollment swelled from nine to thirteen and then to twenty-two, with students from New York, Philadelphia, Providence, and Boston. Within Connecticut, students came from Canterbury, Griswold, and New Haven.10 Crandall finally had the income she needed to meet her basic expenses. Students filled the schoolhouse, and Crandall immersed herself in the job of teacher and headmistress of a school for black women. “In the midst of this affliction I am as happy as at any moment of my life—I never saw the time when I was the least apprehensive that adversity would harm me,” Prudence wrote. “I have put my hand to the plough and I will never, no never look back—I trust God will help me keep this resolution.”11

Crandall’s work mirrored the ongoing efforts of black leaders and ministers in New York City, who operated schools for members of their congregations with guidance in “morals, literature, and mechanical arts.”12 In the spring of 1833, Reverend Samuel Cornish, Theodore Wright, Peter Williams, and Christopher Rush founded the Phoenix Society. They successfully opened a high school for young black men, and later opened a school for black women.13 Both Arthur Tappan and his brother Lewis helped in the effort—Arthur served as treasurer, and Lewis taught at a Sabbath school sponsored by the Society.14 Rev. Cornish wrote that the schools served as “seed sown in good ground,” leading to better lives for people of color.15 Cornish appealed to the community for donations of books, maps, and supplies for the education of black students. The Phoenix Society received many donations as a result of Cornish’s appeal.16

Prudence Crandall could only dream of such a scenario.17 In Canterbury, no one solicited contributions for her school. Instead, local officials lobbied the legislature to pass laws to close it. Andrew Judson and nine other men circulated petitions calling for an end to “the evil consequences of bringing from other States and other towns people of color for any purpose.”18 Sixteen Connecticut cities and towns sent petitions to the legislature supporting the law proposed by Judson. The petitions contained the same language: “We consider the introduction of the people of color into the state … as an evil of great magnitude, as a calamity,” and the resulting “burdens of pauperism … (will) render less secure the person and property of our own fellow citizens.”19

The legislature also received a letter from Prudence Crandall’s father. Pardon expressed his disappointment with local officials, who sought to destroy his daughter’s school rather than encourage the education of black women. “I entreat the members of the General Assembly, when acting on this petition, to remember those self-evident truths, that all mankind are created free and equal, that they are endued with inalienable rights, of which no man nor set of men have a right to deprive them. And my request is, that you will not … pass any act that will curtail or destroy any of the rights of the free people of this State or other States, whether they are white or black.”20

State Senator Philip Pearl chaired the committee considering Judson’s proposal. Pearl lived in Hampton, and his daughter had attended Prudence Crandall’s school until she was dismissed with the other white students. The committee reviewed the petitions and quickly drafted a report.21 In a preface to its findings, the committee discussed the evils of slavery but noted, “Our obligations as a State, acting in its sovereign capacity are limited to the people of our own territory.”22 Senator Pearl concluded that the Constitution denied blacks the basic rights of citizenship.

“It is not contemplated for the Legislature to judge the wisdom of that provision of the Constitution which denies the franchise to the people of color; but your committee are not advised that it has ever been a subject of complaint,” Senator Pearl wrote.23 The report said the legislature “ought not to impede” the education of blacks who lived in Connecticut, but concluded that the state had no duty to educate blacks from other states. “Here our duties terminate,” Senator Pearl said.24 “We are under no obligations, moral or political, to incur the incalculable evils of bringing into our own state colored emigrants from abroad. … The immense evils which such a mass of colored population would gather within this state … would impose on our own people burdens which would admit no future remedy, and can be avoided only by timely prevention.”25

As the Connecticut legislature considered the law proposed by Andrew Judson, an article in the Liberator titled “More Barbarism” attacked those in Canterbury who charged Ann Eliza Hammond with violating the vagrancy law. William Lloyd Garrison was on a lengthy voyage to England at this time; George Bourne or Oliver Johnson wrote the forceful Garrison-style prose. “Georgia men-stealers have never been guilty of a more flagrant and heaven-daring transgression of the laws of humanity … Andrew T. Judson and his malignant associates bid fair to eclipse the infamy of Nero and Benedict Arnold!! … Shame to the Persecutors! Burning shame to the gallant and noble Inflictors of stripes upon innocent and studious Females!”26

After reviewing the petitions in support of Andrew Judson’s legislation, Senator Pearl and his committee decided that black migration from other states into Connecticut posed a serious threat to the state’s safety. “The dangers to which we are exposed … evince the necessity in the present crisis of effecting legislative interposition,” Pearl concluded.27 Pearl’s committee submitted its report together with Judson’s draft of a bill for the legislature to consider. The cumbersome title of the bill, “An Act in Addition to an Act Entitled ‘An Act for the Admission and Settlement of Inhabitants of Towns,’” led others to refer to it simply as the “Black Law.” It repealed the provisions of the old vagrancy law that permitted public whipping on the naked body—legislators agreed this corporeal punishment did not enhance the image of the state—and added new language that empowered towns to ban and prosecute those who assisted in teaching any “colored persons who are not inhabitants of this state.”28 Any person wishing to teach blacks from other states could do so only after securing permission, in writing, from the local town officials. The law also included a series of substantial fines for anyone who violated the new law: one hundred dollars for the first offense, two hundred dollars for the second offense, and doubled accordingly for succeeding offenses (for perspective, the typical wages of the day for mill workers and tradesmen in New England ranged from $.90 to $1.50 per day).29 Even a wealthy patron such as Arthur Tappan would find it difficult if not impossible to pay multiple and continuous fines, always doubling in their amounts.

The law imposed the same escalating fines on anyone who aided or assisted the school.30 Andrew Judson added this language—whereby the state could prosecute any merchant who sold items to Crandall for “aiding and assisting” the illegal school—to help enforce the informal embargo against Prudence Crandall. Judson also claimed this provision prohibited Prudence Crandall’s mother and father from delivering food or clothing to the school and her sister Almira from teaching at the school.

No doubt as a result of Judson’s considerable experience as a prosecutor, the legislation also made it easier to obtain testimony from witnesses for use as evidence at trial. The bill stated that any black student from another state “shall be an admissible witness in all prosecutions … and may be compelled to give testimony.”31 In the event that Prudence Crandall continued to operate her school in violation of the law, Judson wanted to ensure that the prosecution had the means necessary to obtain evidence and testimony from the students.

During the month of May, the legislature accepted and reviewed public input concerning the proposed statute, including Pardon Crandall’s letter. Senator Pearl then submitted his committee’s final report to the legislature, together with the legislation drafted by Andrew Judson. One commentator wrote, “Prudence’s opponents in Canterbury represented no particular villainy of that community but an aspect of human nature at large … ‘We should not want a nigger school on our common,’ was said by many persons in other Connecticut towns.”32 House Speaker Samuel Ingham certified passage of the law on May 24, 1833, and it passed the Senate with Lieutenant Governor Ebenezer Stoddard presiding. Shortly thereafter, Governor Henry W. Edwards officially signed it into law. The “Black Law,” designed to close Prudence Crandall’s school and keep blacks from other states out of Connecticut schools, was officially the law of the state.

In Canterbury “joy and exultation ran wild.”33 The bell of the Congregational Church rang throughout the day. As Samuel May recalled, “All the inhabitants for miles around were informed of the triumph.”34 Jubilant townspeople fired a cannon near the town center and gathered at Andrew Judson’s home. “His success in obtaining from the legislature the enactment of the infamous ‘Black Law’ showed too plainly that the majority of the people of the State were on the side of the oppressor,” May wrote. “But I felt sure that God and good men would be our helpers in the contest to which we were committed.”35

The events at the state capital and the subsequent celebration of the “Black Law” did not go unnoticed by the students at Prudence Crandall’s school. On the day that Judson’s legislation became law, the students sought support and reassurance from the teachers and staff. Would Prudence Crandall send the out-of-state girls home? Would the school close? A few students took the time to write about what they saw and experienced at the school. “Last evening the news reached us that the new law had passed,” one student wrote in a letter to the Liberator. “The bell rang, and a cannon was fired for half an hour. Where is justice? In the midst of all this, Miss Crandall is unmoved. When we walk out, horns are blown and pistols fired.”36

After the initial celebration of the Black Law, townspeople increased their harassment of Prudence Crandall and her students. “The Canterburians are savage—they will not sell to Miss Crandall an article at their shops,” a student wrote. “My ride from Hartford to Brooklyn was very unpleasant, being made up of blackguards” (blackguard was a term used to describe scoundrels or thugs).37 After the stagecoach dropped the student off in Brooklyn, she could not find anyone willing to drive her to Crandall’s school in Canterbury. “I came on foot here from Brooklyn. But the happiness I enjoy here pays me for all. The place is delightful; all that is wanting to complete the scene is civilized men.”38

Prudence Crandall and her supporters continued operating the school as if nothing had happened at the state capital. Crandall told her students the school would remain open. Despite taunts and threats from townspeople, the students stayed on at Crandall’s school and continued their lessons.

The sight of Liverpool, England, delighted an otherwise fatigued William Lloyd Garrison. His passage from New York took twenty-one days and was “inexpressibly wearisome both to my flesh and spirit.”39 Because of the “all disturbing influences of wind and water,” Garrison became seasick while the New York harbor was still in sight. “There is some dignity in falling after a host of stout bodies,” Garrison said, “but to be cast down when delicate females and bird-like children bear up bravely against the enemy is weak indeed!”40

On his arrival in England, Garrison saw the same sights and contrasts that Charles Dickens reported in the early 1830s. Garrison noted that “in England, there is much wealth, but also much suffering and poverty.”41 Liverpool was one of the busiest harbors in the world in 1833. Once called the “metropolis of slavery,” Liverpool was the primary entry port for Europe’s slave trade until England abolished the importation of slaves in 1807.42 Garrison did not see the city as conducive to residential life. “Let this suffice—it is bustling, prosperous and great. I would not, however, choose it as a place of residence. It wears a strictly commercial aspect,” Garrison wrote. “My instinct and taste prefer hills and valleys, and trees and flowers, to bales and boxes of merchandise.”43

Garrison may have recalled the landscape of Friendship Valley, the home of the Benson family in Brooklyn, Connecticut, or perhaps Haverhill, Massachusetts, home of Harriet Minot, where “sweet is the song of birds, but sweeter the voices of those we love,” as he wrote to her at the beginning of April.44 Garrison traveled on to London and began his intended work in England; he sought out potential donors to the abolitionist cause, promoted immediate emancipation, and challenged colonization supporters to debate.

The passage of the Black Law provoked a new battle in the newspapers regarding Prudence Crandall’s school. In a letter to the Emancipator, a New York-based abolitionist newspaper, a writer identified only as “Justice” attacked those who “violate their trust, infringe the rights of citizens and overlap the boundaries of the constitution.”45 Passage of the law was disgraceful, unconstitutional, and unjust, according to the writer. “I ask, has not enough been shown to stamp the deep brand of foul disgrace on all who have aided in the passage of this law or joined in its clamorous celebration?” The writer speculated that allowing blacks access to education “might seriously endanger that superiority in intellectual attainments which the whites at present boast, and also a more immediate consequence might mortify the pride of A. T. Judson, candidate for Congress and Captain Richard Fenner, rum retailer on the Canterbury Green.”46

A letter appeared in the Hartford Courant on June 24, signed “Canterbury,” that sarcastically condemned the new law. “The law does not prohibit colored people coming into the state—this you know would be against the Constitution of the United States—but it declares they should not be instructed. And why should they be? They are not white and it is doubtful if they have souls or will exist in a future state.”47 Connecticut had “taken her stand” against the “wicked and romantic act of putting down slavery,” the writer mockingly said, and had defended the planters of the South who were the true lovers of liberty.48 “I have long been convinced that nothing is more false than the specious statement in the Declaration of our Independence ‘that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights … that none are entitled to exclusive privileges from the community,’ this is all flummery. Let us rejoice that the time has come when our political leaders have dared to abrogate these heretical and pestilential notions.”49 The author said the law was “an enduring monument of glory,” and “the inspiration of a distinguished statesman from Canterbury.”50

During this same time, notices sincerely praising Andrew Judson and the Black Law also appeared. The directors of the Windham County Colonization Society appointed Andrew Judson as the agent and orator of the Society and said he “was the man they delighted to honor.”51 The pages of the New York Commercial Advertiser were “loaded with criminations of Miss Crandall, and vindications of the Black Act.”52 The Advertiser said of Judson, “a warmer heart than his throbs in few bosoms, and the African race has no firmer friend than him.”53 Most newspapers supported the Black Law. “The inhabitants of Canterbury … [are] as quiet, peaceable, humane and inoffensive people as can be named in the United States,” said the editors of the Advertiser. They said the New York State Legislature should consider a law similar to Connecticut’s Black Law “to prevent our charitable institutions from being filled to overflowing with black paupers from the South, and white paupers from Europe.”54

Two weeks after passage of the Black Law, Andrew Judson paid a visit to Pardon Crandall and his wife, Esther. Judson wanted to discuss Pardon’s letter to legislators and the severity of the sanctions in the new law. “Mr. Crandall, when you sent your printed paper to the General Assembly, you did not injure us, it helped very much in getting the bill through,” Judson told Pardon. “When they received it every man clinched his fist, and the chairman of the committee sat down and doubled the penalty. Members of the legislature said to me, ‘If this law does not answer your purpose, let us know, and next year we will make you one that will.’”55

Judson told Pardon the new law would bankrupt those who assisted Prudence’s school. “Mr. Crandall, if you go to your daughter’s you are to be fined $100 for the first offence, $200 for the second, and double it every time,” Judson said. “Mrs. Crandall, if you go there, you will be fined and your daughter Almira will be fined, and Mr. May and those gentlemen from Providence, if they come there will be fined at the same rate.”56

Judson said he intended to use the full force of the law to arrest Prudence Crandall and close her school. “Your daughter, the one that established the school for colored females, will be taken up the same way as for stealing a horse, or for burglary,” Judson said. “Her property will not be taken but she will be put in jail, not having the liberty of the yard. There is no mercy to be shown about it!”57

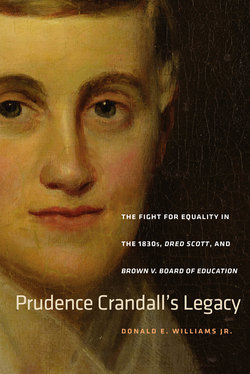

31. Engraving inspired by Crandall’s school and the refusal of the Canterbury Congregational Church to admit Crandall’s students.

Colored Scholars Excluded from Schools. From American Anti-Slavery Almanac for 1839 1, no. 4 (Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1839), 13.

Samuel May and George W. Benson traveled from Brooklyn to Canterbury to visit Crandall and discuss the future of her school.58 If Crandall dismissed the out-of-state students in order to comply with the Black Law, the school would not survive financially; there were not enough local black students whose families could afford the tuition. Neither Crandall nor her supporters wished to capitulate to the new law. They settled on a course of civil disobedience and wasted no time in preparation for her likely arrest and trial.59

May urged Crandall to challenge her opponents, “to show to the world how base they were, and how atrocious was the law they had induced the legislature to enact—a law by the force of which a woman might be fined and imprisoned as a felon in the State of Connecticut, for giving instruction to colored girls.”60 May previously had encouraged Crandall to allow Ann Eliza Hammond to risk a public whipping for violation of a vagrancy law in order to reveal the despicable nature of their opponents. Crandall had declined and paid a fine because she wanted to protect her students. Under the new law, however, those who risked prosecution were not the students, but rather the teachers and supporters of the school. Without hesitation Crandall agreed to challenge Judson and his allies and risk arrest, fines, and jail pursuant to the Black Law.61

With Crandall’s knowledge and consent, May and Benson reached out to those who were sympathetic to Crandall and her school and asked for restraint in the event of her arrest. “Mr. Benson and I therefore went diligently around to all whom we knew were friendly to Miss Crandall and her school, and counseled them by no means to give bonds to keep her from imprisonment,” May wrote. “Nothing would expose so fully to the public the egregious wickedness of the law, and the virulence of her persecutors, as the fact that they had thrust her into jail.”62

Prudence’s younger sister Almira turned twenty years old on June 27, 1833. The school for black women had existed for nearly three months, and Almira played a critical role. She worked and taught there every day; when Prudence Crandall traveled to Providence, Norwich, Boston, New York, or elsewhere, Almira managed the school. Rev. May, who also taught at the school, gave Almira great credit for the school’s survival. “Miss Almira Crandall, though she did not plan the enterprise, has given it from the beginning her unremitted co-operation,” May wrote. “Let her praise therefore be ever coupled with that, which is her sister’s due. Having partaken largely in the labor, anxiety, and suffering, let her share as largely in the reward.”63

Almira’s birthday celebration did not last long. That morning, only four weeks after passage of the Black Law, deputy sheriff George Cady arrived at the school and presented Prudence and Almira with arrest warrants. The two sisters were accused of “instructing and teaching certain colored persons, who at the time so taught and instructed were not inhabitants of any town in this state.”64 The warrants also charged Prudence and Almira with “harboring and boarding certain colored persons” from out of state. The Crandall sisters were charged with teaching black women from other states without written permission from the selectmen of the town, as required by the new law. The deputy sheriff told them that he was “commanded forthwith” to arrest Prudence and Almira Crandall and bring them before attorney Rufus Adams, justice of the peace, to be “dealt with there on as the law doth require.”65

Prudence Crandall had discussed this scenario with her family and staff and had prepared for this moment, yet it nonetheless came as a terrible shock. Her students were stunned at the sight of the sheriff arresting both Prudence and Almira and leading them away from their school. Prudence told her assistant Mariah Davis to go immediately to her father’s house and tell him of the new developments.66 The sheriff then escorted the sisters out the front door of the school to a waiting carriage and drove them to the house of Chauncey Bacon, where Bacon and Rufus Adams formally charged them with the crime of violating the Black Law.

Later that day, a messenger raced to Rev. May’s home. May was told that a sheriff had arrested Prudence Crandall and her sister Almira, but the charges against Almira were dismissed—she was not yet twenty-one years old and was still a minor.67 The messenger told May that Prudence Crandall remained in custody. May did not know the messenger, who likely was sent by Andrew Judson or Rufus Adams. The man told May that he or one of Crandall’s friends should post her bail—$150—or else Prudence Crandall would spend the night in jail.

“There … (are) gentlemen enough in Canterbury whose bond for that amount would be as good or better than mine, and I should leave it for them to do Miss Crandall that favor,” May told the messenger.68 “But, are you not her friend?” the messenger asked. “Certainly,” May replied. He said Miss Crandall did not need his help, and her accusers would be embarrassed by her unjust arrest.69

“But, sir, do you mean to allow her to be put into jail?” the man asked. “Most certainly,” May replied, “if her persecutors are unwise enough to let such an outrage be committed.” May wrote that the man “hurried back to tell Mr. Judson.”70

Crandall’s supporters had already investigated the arrangements for her stay at the Brooklyn jail. In response to a question from Samuel May, prison officials said that Crandall likely would stay in an unoccupied room that two years earlier held a notorious murderer, Oliver Watkins. Watkins had strangled his wife with a whipcord. He was convicted and sentenced to death by hanging. Local tavern owners had anticipated a huge crowd and brisk business on the day of Watkins’s execution. They had ordered additional rum and spirits and hired an extra guard at the prison to monitor Watkins so he would not commit suicide.71 The tavern owners persuaded the authorities to move Watkins to the debtor’s room, where he was more easily monitored.

On the day of the hanging, August 2, 1831, wagons and carriages jammed all of the roads leading into Brooklyn, and an immense crowd gathered. Men filled the taverns. Historian Ellen Larned wrote that the execution was carried out “in stillness that seemed of the dead rather than that of the living.”72 The silence, however, quickly disappeared. “The vast throng present, the abundant supply of liquor and scarcity of food made the afternoon and following night a scene of confusion and disorder.”73

The officials at the Brooklyn jail said that Prudence Crandall would stay in the debtor’s room previously occupied by Oliver Watkins. May considered this good news. The notoriety of the Watkins execution was fresh in the minds of Windham County residents; May believed jailing Prudence Crandall in the same prison room where Watkins stayed “would add not a little to the public detestation of the Black Law.”74

May gathered fresh linens from the Benson family, who lived a short distance away, and remade the bed at the jail. He brought an additional bed into the debtor’s room so that Anna Benson—who did not want Crandall to spend the night in jail alone—could stay in the room with Crandall.75 At two o’clock in the afternoon, another messenger told May that if he did not post Crandall’s bail immediately, a sheriff would transport Crandall from Chauncey Bacon’s house in Canterbury to the jail in Brooklyn. The opponents of the school suddenly realized that locking Prudence Crandall in the Brooklyn jail might result in sensational news stories casting Canterbury and the Black Law in an unfavorable light. May refused to pay Crandall’s bail. Instead, he traveled with George Benson to the jail. When Crandall’s carriage pulled up to the prison entrance, May and Benson greeted her. May spoke with her before the sheriff led her inside.76

“If now you hesitate, if you dread the gloomy place so much as to wish to be saved from it, I will give bonds for you even now,” May told Crandall.77 “Oh no,” she replied. “I am only afraid they will not put me into jail … I am the more anxious that they should be exposed, if not caught in their own wicked devices.”78

Sheriff Roger Coit slowly led Crandall down the walkway to the entrance of the jail. “He was ashamed to do it,” May wrote.79 Before Coit took Crandall through the door, he looked to see if someone might rush forward with the bail for Crandall’s release. Coit whispered to two men standing nearby. The men walked over to May and made one last plea for Crandall’s bail. “It would be a shame, an eternal disgrace to the state, to have her put into jail, into the very room that Watkins had last occupied,” they told May.80 “Certainly, gentlemen,” May replied, “and you may prevent this.”81

“We are not her friends …” the men said, “we don’t want any more niggers coming among us. It is your place to stand by Miss Crandall and help her now. You and your abolition brethren have encouraged her to bring this nuisance into Canterbury, and it is mean (for) you to desert her now.”82

May told the men he had not deserted Crandall. He candidly told them that Crandall’s arrest and prosecution would help expose the infamous Black Law. May said the people of Connecticut would not “realize how bad, how wicked, how cruel a law it is, unless we suffer her persecutors to inflict upon her all the penalties it prescribes. … It is easy to foresee that Miss Crandall will be glorified, as much as her persecutors and our State will be disgraced, by the transactions of this day and this hour.”83

The men cursed May, and Sheriff Coit led Crandall into the debtor’s room where Oliver Watkins had spent his last night. As May and Benson walked from the jail to May’s carriage to return home to Brooklyn, May noticed the sunset. “The sun had descended nearly to the horizon; the shadows of night were beginning to fall around us. … So soon as I had heard the bolts of her prison-door turned in the lock, and saw the key taken out, I bowed and said, ‘The deed is done, completely done. It cannot be recalled. It has passed into the history of our nation and our age.’”84

After the tumult of the day, the night passed quietly. On Friday, George Benson posted the bond for Prudence, and she was set free on bail awaiting trial. As May had predicted, word of her imprisonment spread quickly. Newspapers throughout the country printed stories about the female schoolteacher who had spent a night in jail for the crime of teaching black women, including the Liberator, where guest editors Oliver Johnson and George Bourne continued to write and publish in William Lloyd Garrison’s absence.

“Savage Barbarity! Miss Crandall Imprisoned!!! The persecutors of Miss Crandall have placed an indelible seal upon their infamy!” the Liberator screamed. “They have cast her into prison! Yes, into the very cell occupied by Watkins the Murderer!!”85

In response to the sensational news accounts, Andrew Judson received threatening letters from readers throughout the Northeast and as far away as Pennsylvania.86 One person had a unique proposal. The man offered to “jail” Judson in a portable cage and display him for the curious of England and France. The man promised “good food and no whipping or compulsion unless absolutely necessary.”87

Crandall’s opponents tried to counter the bad press with their own letters. They questioned the assertion that Crandall had spent the night in the same prison cell used by a murderer. “Some person has put in wide circulation the story that she was confined in the cell of Watkins the murderer,” Andrew Judson and Rufus Adams wrote in a joint letter. “This is part of the same contrivance to ‘get up more excitement.’ She never was confined in the murderer’s cell. She was lodged in the debtor’s room, where every accommodation was provided, both for her and her friends, whose visits were constant.”88

The complaining by Judson and Adams did little to counteract the story of Prudence Crandall’s night in jail. Their criticism focused on the word “cell.” They said Prudence did not spend the night in the “cell” where Watkins spent most of his days in jail. Their complaints were trivial and misleading by their own admission; they acknowledged that the debtor’s room where Crandall stayed was the same room where Watkins had spent “the last days of his life … to receive the clergy and his friends.”89

Days after Crandall’s imprisonment, Samuel May received a letter from Arthur Tappan. Tappan may have read one of the many press accounts of Prudence Crandall’s arrest and learned of May’s defending Crandall and her school. While they had not kept in touch, Tappan and May knew each other from years before. Tappan’s father worked as a silversmith in Northampton, Massachusetts, and later went into the dry goods business. In the spring of 1801, when Arthur was fourteen, his father sent Arthur to Boston for an apprenticeship with Sewall and Salisbury, importers and retailers in hardware and dry goods. Tappan stayed for two years and during that time lived with the family of Joseph May, Samuel’s father. Samuel was very young—he was five years old when Tappan finished his apprenticeship—but he knew that Tappan had started his successful business career while living with May and his family.90

The paths of these two men had not crossed often since that time. When May received Tappan’s letter, he recalled that he last saw Tappan ten years earlier in 1823.91 May had followed Tappan’s career and noted that they had significant “theological differences,” most likely regarding Tappan’s interest in the evangelical movement.92 While May did not consider himself “personally acquainted” with Tappan in 1833, he had great respect for his generosity and his willingness to engage in the fight to end slavery in America.93

In his letter, Tappan thanked May for his courageous work on behalf of Crandall’s “benevolent enterprise” and the right of colored people to obtain an education.94 “This contest, in which you have been providentially called to engage, will be a serious, perhaps a violent one,” Tappan wrote. “It may be prolonged and very expensive. Nevertheless, it ought to be persisted in to the last.”95

Tappan knew that neither Crandall nor her supporters could afford the expense of a first-rate legal defense. The cause of equality in education, however, must be sustained, Tappan said. “Consider me your banker,” Tappan told May. “Spare no necessary expense. Command the services of the ablest lawyers. See to it that this great case shall be thoroughly tried … I will cheerfully honor your drafts to enable you to defray that cost.”96 Tappan’s latest act of generosity had a dramatic effect not only on May’s state of mind that day—he was elated—but also on the quality of legal firepower that Prudence Crandall would have on her side. May moved immediately to retain “the three most distinguished members of the Connecticut Bar”: William W. Ellsworth, Calvin Goddard, and Henry Strong.97

The good news from Arthur Tappan was tempered by a series of incidents that threatened to break the spirit of Crandall and the young women at her school. Crandall called the summer of 1833 the “weary, weary days.”98 The excitement of planning and launching the school had transformed into a seemingly endless string of obstacles and grinding opposition. The simple act of buying supplies from a local vendor constituted a violation of the Black Law. The harassment and vandalism that increased after the passage of the law continued. Students worried for their safety.

The court scheduled Prudence Crandall’s trial for August. If convicted of violating the Black Law, Crandall knew that in a few weeks she might face the possibility of large fines that would close her school and destroy her financial future. In early July she came down with a fever. The Liberator attributed her sickness to her stay in prison, but more likely it was related to the stress of the enormous challenge she had undertaken and the responsibility she felt to her students and her family.99 She did not recover quickly and rested for most of the month of July.

During this time, Crandall wrote a song for her students to sing. Crandall later recalled, “Four little colored girls dressed in white sang beautifully the following lines which I composed for them.”100

Four little children here you see

In modest dress appear

Come listen to our song so sweet

And our complaints you’ll hear

’Tis here we come to learn to read

And write and cipher too

But some in this enlightened Land

Declare ’twill never do

The morals of this favored town

Will be corrupted soon

Therefore they strive with all their might

To drive us to our homes

Some time when we have walked the street

Saluted we have been

By guns and drums and cow bells too

And horns of polished tin

With warnings threatened words severe

They visit us at times

And gladly would they send us off

To Afric’s burning climes

Our teacher too they put in jail

Trust held by bars and locks

Did e’re such persecution reign

Since Paul was in the stocks

But we forgive, forgive the men

That persecute us so

May God in mercy save their souls

From everlasting woe101

Throughout the summer, the Liberator published letters from Crandall’s students. Crandall and her fellow teachers likely read and reviewed the letters prior to their delivery to the Liberator. The letters provide an important window into the life of the embattled school. On July 6, 1833, a student wrote of her appreciation for the opportunity to receive an education, but noted that prejudice born in selfishness and ignorance had overshadowed the “bright ray” of knowledge. The student had a pessimistic view of the school’s future.

“From our land Justice seems to have taken her flight … Go tell the people that pride is coiling round their hearts … their tender hearts are growing cold and hardened, the path in which they walk is laid across human beings, and they are crushing them to the earth, beings like themselves, guilty of no other crime than wearing a complexion, ‘not colored like their own.’ If the unrighteous law which has lately been made in this state compels us to be separated, let us submit to it, my dear associates, with no other feelings towards those that so deal with us, than love and pity.”102

Prudence Crandall and her students prepared for the intense challenges that loomed in the weeks and months ahead.