Читать книгу Why I Won't Be Going To Lunch Anymore - Douglas Atwill - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Deathbed of Cecily Brompton

ОглавлениеOne day in the summer of her ninety-first year, Cecily Brompton, after a lifetime of good health, avoiding minor colds, broken bones or major illness of any sort, took to her bed at the unaccustomed hour of nine in the morning, feeling very unwell. Her bedroom, a small cell with an iron-frame single bed, adjoined the Santa Fe studio where the work on her newest painting was not going well.

The household staff did not notice her departure from the studio, as they provided her complete privacy during the morning hours, her best hours for painting. She had trained the staff to make no noise or disturbance during these important early hours. At noon, the cook, Isabel Rodriguez, was instructed to check quietly into the studio. If work was going well there, she adjusted the serving of the midday meal accordingly.

The entire staff was aware of the necessity for seamless quiet in the home studio of the most important woman artist of the western world, as the art magazines had it. Brompton herself rankled at the adjectives “woman” and “western,” preferring to think of herself as the most distinguished painter alive, not merely an American female version of greatness. After all, Picasso, Matisse and O’Keeffe were all dead. Since her paintings sold for vast sums soon after they were delivered to her New York gallery, who could question her self-assigned spot at the top of the list? Collectors on both sides of the Atlantic lined up to purchase a prized new Brompton, an icon for success on sitting room walls the world over.

The four people who comprised the Brompton household, the cook, maid, driver and gardener were justly proud of their employer and furthered the cause of art and fame like a trusted palace guard. Isabel Rodriguez was the liaison between Brompton and the rest, nurturing the pride of servitude and quelling any disturbances. Few people got past this phalanx without permission to interrupt Brompton’s work.

The staff had learned to assess the situation without words; they sensed the direction work in the studio was taking and awaited Brompton’s re-emergence from her workplace at whatever hour she chose. So that was how the staff missed the start of Brompton’s malaise and her odd retreat to her mid-morning sickbed.

For two hours she slept fitfully, dreaming of brightly costumed dancers emerging from and retreating into a roiling wall of mist. She had this dream several times before and now, waking around eleven in the morning, made a painter’s practiced effort to remember the bold black and white patterns of the dancer’s costumes and small details of the dances. The sketchbook on the bedside table was full of quick renderings of dream images.

As she came up through the levels of sleep to awareness, the curious situation of her in bed at this hour startled her away from this happy reverie of remembrance. What did this being in bed at mid-morning mean? Was this unfamiliar weakness a prelude to something dark and final? Was this her deathbed?

She had always imagined she would go suddenly. As the years went by she formulated ever more dramatic scenarios for this finale: a private plane, solid maroon in her vision, plummeting down to winter seas off a storm-tossed coast, perhaps the rocky Atlantic side of Cornwall; a pistol shot from a crazed, foreign admirer in a Turkish military uniform, handsome with elaborate epaulettes and black boots; or, her favorite, because of its visual tension, a motor accident, the Mercedes with her at the wheel careening off an icy curve into an ultimate, smoky spiral down to the Rio Grande River, exploding in the dark New Mexico night, a night of festivities elsewhere. A satisfying show of concluding drama. A flamboyant death to match her eminence, not the slow wasting away that this morning in bed foretold.

A death at home in bed was for a rich dowager without artistic worth, not the painter that the world idolized, the artist that women everywhere took as a role model for female success in a man’s world. Furthermore, it would be a bore to die slowly in bed with wailing servants and long-faced associates to visit you, and then to depart with an audience of dull and sanctimonious faces. It would be a flat, atonal finale to what had been a glorious symphony. As she arrived at full consciousness, Brompton was very dissatisfied with this turn of events.

The cook found her. Isabel, after she saw the studio empty, quietly opened the closed bedroom door, let out a short cry to find Brompton in bed. In a flash she knew what it portended.

“Senora, you are ill.” she said, half a question.

“Yes, Isabel, it would seem so.” Brompton was annoyed with herself and her tone was clipped and harsh.

“I will call Dr. Harmon,” she said as she came near to feel Brompton’s forehead.

“Don’t fuss, Isabel.” She brushed her hand away. “I’ll have lunch here in the bedroom. Only broth and some toast, please.”

This was the day the staff knew would come, the end to their comfortable world. Cecily Brompton would die soon, Isabel thought, leaving their days empty but perhaps their bank accounts full of the expected bequests. The staff had discussed this day and what their inheritances might be.

Patricio, the driver, told the others that his legacy would be the largest as the Senora had always been in love with him. He said he saw her admiring him in the mirror when they drove in the Mercedes about Santa Fe. Cecily Brompton admired male beauty and all the drivers before Patricio had been handsome and young. Patricio counted on a large inheritance.

Isabel disagreed, saying that she and the Senora were like sisters, sharing decades of secrets and stories. The maid and the gardener knew their bequests would be smaller, but, considering Senora’s great fame and wealth, they knew that some substantial sum would come their way.

Now that this sad day was almost here, Isabel lost her voice to a whisper. She backed out of the bedroom door.

“Yes, Senora. I will call Dr. Harmon. Now.”

Thus the rhythm of her terminal days was set: insubstantial meals with naps throughout the day and fitful nights of sleep, short daily visits from Dr. Harmon. Weeks went by and there was no change in this pattern, excepting the increased volume of worried visitors. Her condition worsened as the number of bedside guests grew.

The new painting remained unfinished in her studio, the brushes stuck in the thickening paint of her palette. No one was allowed into her studio. Her gallery owners made several visits, her lawyer, her banker and a few of the few friends she had left. Isabel, hurling Spanish invective on their heartless heads, sent writers from the art magazines away with gusto.

On the fifth week of Brompton’s time in bed, Isabel arrived one morning with a bouquet of wildflowers, obviously picked along the road. She had a conspiratorial smile. “Your second-cousin, Carlos, is here to see you, Senora.”

“Isabel, I don’t have a second cousin.”

“Maybe you don’t remember that your great-aunt’s daughter, Mrs. Barrington, had two children, Carlos and Emilia. She was married to the man from Barcelona.” Isabel enjoyed pronouncing that with a rolled ‘r’ and a long ‘th’ sound. How family charts flowed in the Rodriguez family was very important to Isabel, and to lesser degree family charts in general. Where people fit into the scheme of things mattered to her. The fact that she knew more about the Senora’s family than she herself pleased Isabel enormously.

Brompton said, “That’s nonsense, Isabel. Send him away.”

“But the povrecito has come all the way from España to see you, to help you to get well.”

“So he’s a healer, as well as a cousin. Amazing lad. Isabel, he’s only an imposter.”

“He’s very charming and very handsome, Senora.”

“Oh, very well. Bring him up.” Isabel knew what mattered to the Senora.

In a few minutes, the door opened and Isabel presented Carlos with a proud flourish, as if she had cooked him up in the kitchen herself. She watched as Brompton looked up at the redheaded, brown-eyed young man. He sat down in the bedside chair reserved for visitors, putting his large hands on his knees; his lanky frame rested uneasily in the small, creaking chair. Isabel left and closed the door quietly.

Brompton said, “So you’re my cousin. Indeed.”

“Sorry about that. It’s only a small lie.”

“They are the worst, those small lies. Nations fall because of them.”

“I knew I needed to be family to get past Mrs. Rodriguez and my Spanish is good enough to convince her.”

“Your Spanish must be very good, then. If you’re not a cousin, who are you?”

“I’m here to look after you,” he said.

She laughed quietly and said, “I wish I’d heard those words sixty years ago”.

“I can make your life easier and help you paint. That is, to get back to painting.”

“I’ve never needed help painting. I detest someone else in my studio.”

He was insistent. “But you may need help now.”

“That’s true, alas.” Brompton paused and considered the young man. He appeared to be serious and concerned. What exactly could he do to help? Nobody had ever been able to assist her in the studio, so why now?

She continued to look at him in silence and he showed no outward signs of nervousness or guilt. Brompton set great store in her ability to watch a face and judge character. Carlos did not appear to be a thief or assassin. At worst, he seemed only an opportunist. Appraising her own position, Brompton thought that if she continued staying in bed, she would certainly be dead in a month or two, if only from boredom.

“Carlos, is it?” He nodded. “How did you know I was ill and not painting? Did a bright star appear on the western horizon?”

He smiled. “Your gallery people in New York told me. I was there studying your latest paintings. I’m a beginning painter myself.”

“What makes you think you are competent to assist me in any way? What do you know of my work?” she said. He smiled broadly again and Brompton tried to remember the Spanish words for the adage that the best passport in life is great beauty.

He said, “I’ve looked at your paintings a long time. I spent weeks at the Tate, going back day after day. And the same at the Beaubourg and the Whitney.”

“And what did you find?”

“I see great beauty in Number Three Forty-Seven and Number One Nineteen. Both at the Whitney. I also think it would be a shame for the world if you did not paint more in the vein of Number Four Eighty-Nine, now on display at the Tray Gallery on Madison Avenue. You have more to paint, I am sure.”

Brompton was impressed with this young man. Those numbers, the only titles she ever gave to her work, were among her dozen favorites in her entire oeuvre. She was not sure, herself, why she liked them so much better than the rest. Nowhere were these listed and to nobody had she ever told these foremost choices. He must have come up with these opinions on his own. This young man had said the magic words, and even if he were a scoundrel and a pretender, she would now have to see what he could do.

“Carlos, let’s see how I feel in the morning. I am tired now. Isabel will find you a guest room. We’ll talk more tomorrow.” She closed her eyes and the interview was over. Carlos left quietly.

The next day Isabel noticed a marked improvement in the Senora when she came into the bedroom. Her intuition had told her that there was a good quality in this young man who said he was a cousin but was not a cousin, something good for the Senora. If Isabel did not believe his cocked-up stories in broken Spanish, she did believe in omens and Carlos was a true omen. Isabel asked, “Would Senora take breakfast today?”

“Yes, Isabel. Some strong coffee. Eggs and sliced oranges, like before. And a muffin with the English marmalade.” Afterwards, Brompton spent a minute or two in front of the mirror. The white dress instead of the black one. Her hair, pure white, was long and abundant and still looked right just combed and knotted into a bun. Her face was wrinkled from so many years in the western sun, but her neck was firm and her chin without sags.

She considered with approval her legs, slim and well turned after all the years of standing at the easel. She thought if the deathbed was really calling for Brompton, it was getting an unusually well-preserved specimen. How fortunate death was.

She walked slowly into her studio and, from a chair, looked at the unfinished canvas on the easel. Now, after these many weeks, she saw it with a new eye and judged it a surprisingly good start. The long lines of the composition had life; they had those vibrations that came like voices, sometimes, and never on demand. Could she pick up the moment again and continue?

A great tired cloud overcame her previously excited thoughts. It would be too much work to get the energy level up again, up to a point where the brush flowed with paint like a long-distance runner. The paints on the table must be discarded, new ones and new brushes brought from the shuttered cabinets against the wall. Maybe this was all a bad idea. Go back to bed and say goodbye.

Carlos came in the other door. “You look unhappy.”

“I am. This will not work. Let’s not even try.”

“Sit down, please. I will clean up your paints and brushes. I won’t take twenty minutes.” Without her prompting, he went to the sidewall cupboards and selected brushes and paints. He discarded everything on the table and started arraying the tubes behind the marble slab Brompton used as an easel.

“Cool colors on the left,” Brompton said as Carlos was about to put them on the right.

Carlos then scraped the dried paint off the marble with a razor and washed it clean with turpentine. He placed the linseed oils, thinners and mediums behind the paints and looked at Brompton for approval.

She nodded. “There’s a brush you’ve thrown out that I want back. It has a chisel end, maybe an inch wide. I am sure it can be restored.”

He found it, heavily encrusted, and without comment, took it with him as left the studio.

Brompton had to admit now that the painting table was in order again, her spirits returned. Maybe Carlos would work out. Only as a studio aide, of course. She painted an hour that morning and there was a definite seam between where she left off weeks before and this new work. But Brompton thought the seam had validity. What was, was. She did not attempt to hide it, but continued on with her long vibrating lines, top to bottom. Here it was, a painting that documented her life with a validating division between work shut down and work regained.

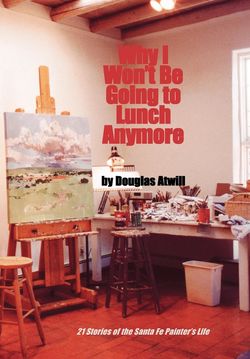

The next day she painted for half an hour longer, with Carlos sitting quietly against the far studio wall. This was the studio that Brompton had kept secret from the world for half a century. It was rumored to be the ultimate in spare and elegant beauty, which art publications around the world yearned to photograph.

It had high ceilings of white beams, unadorned walls on three sides with high casement windows on the east. No memorabilia strewn about, only pristine whiteness on every surface. Even the easel had been painted white.

Her view of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains was devoid of neighboring houses or roadways. It was a panorama unchanged in the forty years of her occupancy, unchanged since ancient times. The morning sun streamed in at an angle, lighting the wall opposite the easel wall.

Brompton had been zealously private all these years, never sharing her workspace. Now this young Carlos sat impassively in the corner of the studio while she painted. After the first few days of this arrangement, Brompton in her mind extended Carlos’s temporary visa and thought she would allow him to stay only until this painting was done. Perhaps for a week more at the most.

Carlos was a quick study with her preferences. He learned she wanted the marble palette to be clean each morning before she arrived. He washed the brushes each night, finishing with a soapy wash to rid all trace of the linseed oil, then a clear water rinse. Tubes were returned to their strict arrangement of violet, blue, green, yellow, orange, and red, left to right, earth colors and whites on the far right.

One day Brompton asked Carlos, who was startled from his reverie against the wall. “Do you believe that beauty continues after death, Carlos?”

He was quick to respond. “Maybe that is the only true beauty.”

Brompton chuckled, “That is a very Zen approach to an answer. So you think that the beauty that survives death is the only true beauty?”

“Of course.”

“So how does beauty survive the buffeting of suffering, envy and greed that surround everything, especially after the creator of that beauty has gone?”

“True beauty has its own power and survives as long as someone thinks it exists,” Carlos said.

“I believe that, too.”

As the days went on, Brompton enjoyed the give and take of ideas from Carlos. They alternated the roles of the inquisitor, questioning the other as the neophyte. Sometimes they turned the qualities of life upside down and threw them like paper gliders back and forth. She finished the painting with the frontier in the middle of it and started another, this time including a mock frontier two-thirds the way across.

Her health grew imperceptibly better, evidenced only by the longer morning hours she could work in her studio. Carlos never left her side in the studio and many mornings there was only silence. She took long afternoon naps and was often too weak to have dinner.

He never asked a question first, waiting for Brompton to introduce a mental puzzle like a seminar professor announcing the subject of the day’s discussion. They spent a week on the nature of truth and several weeks on whether reality is, in fact, illusion. Brompton favored the role of the investigator while Carlos fell naturally into that of the Artful Dodger, slinking around an open response. Isabel often heard laughter from the studio as she passed by the closed door, a strange sound in her years with the Senora.

One day Brompton asked Carlos, “Why, in the scheme of things, is it that I have had so much more success than other painters?”

“You have accumulated merit in a former life. It now shows itself.”

“It’s not that I am better than the others? It’s just that I came with a large metaphysical bank account of merit, a spiritual inheritance?”

“Yes, you have enormously good karma from another life,” he said. “But you are, also, better than the others.”

Weeks grew into months and months finally into a year. Brompton painted six new paintings in that time, inching along. Isabel beamed a continuing consent of what she had conjured, bringing light lunches and, when Brompton felt well enough, spare evening meals for the two of them.

Isabel told others in the staff that the Senora had taken strength from the young omen. Carlos was a young bull who brought new life to the old sacred cow, she said. Sometimes a young male in the pasture could do service for all the old females, if only with fanciful ideas. The maid blushed.

The New York gallery came with a private jet to collect the six canvases, planning an exhibit in the winter season. Brompton left Carlos alone in the studio and spent a morning in discussion of business matters with the gallery people. Then they were gone, people and paintings all, and the studio was empty again. She came back to the studio in the early afternoon and found Carlos still there.

“I think they’ve found a good home,” she said, sitting in the chair next to Carlos.

“The paintings?”

“Yes.”

“They are beautiful. They deserve a good home.”

“What will you do now, Carlos? Do you want to stay on?”

“As long as you need me. I would still like to paint again myself, though.”

She paused, put her hand on his arm, and then walked to the door.

“I’ll get the studio ready for tomorrow, then.”

‘Yes. Thank you, Carlos.”

Brompton did not go back into the studio again. Her condition worsened that night and a few mornings beyond Isabel came wailing down from the Senora’s bedroom with the dark news. The day of death had come.

The staff received the generous bequests they had expected, and Isabel was quick to point out to Patricio that her inheritance was several times the amount of his. The last will and testament set up the house and studio as a foundation with the staff to be kept on indefinitely. There was a coming and going of lawyers, accountants and gallery people. Carlos was not mentioned in the will at all, and no provision was made for his staying on with the Brompton Foundation. To this he showed no reaction.

Isabel felt sorry for him, but not sorry enough to share any of her own bequest. After a month in the mourning household, Carlos left Santa Fe and returned to New York. He got work in a Soho gallery, helping with installations and doing light sales work.

Months passed and he went forward with his life, planning to paint again himself. He thought of renting a studio, but waited with prudence until his commission check from the gallery grew larger.

Then one day a messenger arrived at the gallery with a personal letter for Carlos. It was a blank paper folded around an invitation to the opening night of the latest exhibit at the Tray Gallery. The printed card read “Cecily Brompton, The Final Work. (Numbers Four Ninety through Four Ninety-Five). Opening Reception by Invitation Only.”

Carlos was puzzled about this exhibit. Brompton had told him that they were sold and found a good home. So what was this exhibit all about? He showed up at the appointed hour and viewed the paintings, the six of them widely spaced on the walls of the gallery space.

A crowd started arriving as he studied each painting in turn. He thought back to the mornings in Santa Fe in the light-suffused studio and the happy progression of days as each of these canvases came into being. Perhaps it was time for him to spend a year at the easel himself.

At first he did not read the card beside each of the paintings, remembering each as they were painted. The motif of the frontier in the center of each painting was a bold departure from her earlier work. Carlos heard the words “frontier,” “border,” and “divergence” in the conversations around him. Clearly her collectors understood the importance of these last canvases.

After an hour in the gallery, he bent down to read one of the cards. It said: “Number Four Ninety-One, Collection of Carlos Barrington, Not For Sale.” He checked the other cards and they all attributed his name as the collector.

“Brompton asked me to list these paintings this way,” said the gallery owner when questioned by Carlos. “She said that they are yours but she wished to have this exhibit, nevertheless.”

“But surely they are part of her estate,” Carlos said.

“No,” the gallery owner replied. “On my last visit with her in Santa Fe, Brompton gave me a letter of intent clearly passing title to you. She instructed me to issue a sales receipt and to pay the necessary taxes immediately on my return to New York, which I did. As the last and probably best work, the paintings will demand a premium price should you decide to sell.” The gallery owner’s eyes glistened with anticipation.

Carlos paused a long time before answering. “I don’t believe I do want to sell.”

“These six paintings are an amazing burst of final genius. A super-nova of concluding light from Brompton. You are a very lucky young man.”

Carlos nodded his assent. Beauty had, in its own curious way, survived death. He politely took his leave of the gallery owner and walked through the jostling crowds of a snowy Madison Avenue.