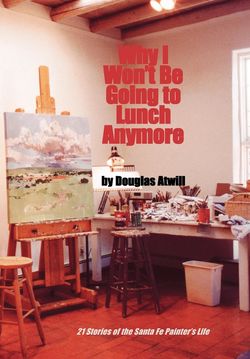

Читать книгу Why I Won't Be Going To Lunch Anymore - Douglas Atwill - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface

ОглавлениеIt was an evening at Fiesta-time. Don’t tell me which ones are artists, my sister-in-law said, let me guess. We took a close inventory of the room, an animated cocktail party for thirty at my neighbor’s house. That attractive woman with the spiked red hair, that lovely old man with expressive hands in the wicker chair, that handsome man in riding boots, the gloomy middle-aged spinster with the dry sherry, the heavy-set woman with circular ear-rings, the Englishwoman, the Italian man, the Navajo, the tall woman with the small head, the woman in bull-fighting costume and the stylish young man in a sixteen-button suit. Those are the artists among them, she said, with a tone of authority. She was wrong, of course, because all of them were artists, the whole room full.

Ask any people on the street what an artist is really like and you get much the same answer. They are always tormented, ego-washed, choosing queer clothes and exaggerated haircuts, sleeping late, never paying their bills, playing loud music, depositing piles of ignitable rubbish on the floors of their studios, disappointing their long-suffering companions, yearning for public love and shocking the innocent, church-going bystander. Everybody knows these things. Artists are monsters. Newspapers, books and TV tell us that they are and thus it must be true. With these stories I will suggest that this is not always the case.

So if you cannot recognize artists by how they look or what they do outside the studio, what does distinguish them from accountants, dentists or the men on the street? There are three sure signs.

Don’t tell me what to do. Short or tall, my painter friends have one attribute in common: a classic, ongoing discomfort with authority. Tell an artist he must do this, merely suggest he might be happier doing that, and watch the predictable fireworks. Where they might listen to small hints of guidance from another painter, they will never welcome or accept it from outsiders.

Please, dear, get out of my studio. They all share a determination to make time for their art, usually to the detriment of their loved ones. You’ve forgotten to keep the cat’s bowl full once again and Grandmother Atwill’s beloved Minton plates pile up in the sink, spaghetti sauce gluing them together. Forget it. Since there is no hope of assuaging the unhappy ones around you, be true to the work at hand, the unfinished canvas on the easel.

I can’t get it quite right. What is in the mind of an artist is always more beautiful, more telling, more truthful than what he can portray on the canvas. It is a lifelong pursuit, but the chase is more important than anything else. Others will be left behind if they try to follow.

It is this painter contingent, with or without stylish haircuts or clothes with curious collars, that concerns me in these stories. They work at their easels, battling the demons that strive to bring a tremble or a moment of indecision to a sure hand. A lonely struggle seen by few witnesses, but, on the other hand, owing little in the way of dues to anybody else.

They are the artists, but also they are the Santa Feans. Trying to make sense of the work of notable artists that went before, the traditional plein air landscapists, the modernists and finding a way to acknowledge the vast beauty that surrounds them, they must stake out their own version of what it is to make art, confounding the conventional wisdom again and again. These are tales of their striving for what it is that makes them different, accomplished. Surely there is a Latin term for ‘seize the brush?’

—Douglas Atwill

Santa Fe, December 2003