Читать книгу Why I Won't Be Going To Lunch Anymore - Douglas Atwill - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Why I Won’t Be Going

To Lunch Anymore

ОглавлениеAlthough it was just before noon on a faultless day in late summer, I had a distinctly uneasy feeling about what would happen at my destination. I was driving in the foothills above Santa Fe to lunch at Donald Strether’s, a lesser known but successful painter of small, modernist abstractions and a dedicated scoundrel. As I drove I mulled over one of my favorite subjects, the making of a living at art and particularly how this Strether made his own ample income from his small paintings.

I painted for a living myself, as did many of my friends. With more than a thousand artists living and working in Santa Fe, it was not so unusual an occupation as it might have been elsewhere. Since the difficulties of harvesting a livelihood out of art were so numerous, my sympathies were always on the side of the artist, even this Strether.

Of all the schemes for carving a living from art, his was one of the more effective. He painted seldom, awaiting the call. When it came, he worked four or five weeks to produce a single canvas. Then he patiently bided his time until he could place that one small painting for an enormous sum. I thought of a garden spider waiting for the single meal of the summer, the meal that would provide until the end of winter. He never started another painting until the last one had been purchased.

In the interim, Strether gardened, sunbathed, meditated, socialized, attended the opera and chamber music concerts and worked on his spare but elegant adobe house. He was tall and darkly handsome and was often included as the extra man at Eastside dinner parties. He discreetly let it be known that a new gem was now available, waiting to grace the walls of some fortunate sitting room. Word spread like thin syrup among the party givers and goers alike.

Hostesses found his brooding nature irresistible and quietly championed his cause. His gloomy demeanor, as if in purgatory already, only added to his charm. They relished providing collectors for his treasured paintings while giving no hint of collusion or design. Allies in the Great War of Art, collaborators in a glamorous cause, they casually seated him next to the lonely bejeweled widow, the CEO’s unhappy wife, the sensitive bachelor or the newly enriched of any sort. By meal’s end the hook was quite often deeply sunk.

The process of a new acquisition had begun. Strether found the gender of the collector unimportant; lunches, dinners and picnics would follow, with overtures of love and promises for an end to loneliness. At the end of several weeks, the purchase of the painting was just one part of many adventures of a summer dalliance. The new collector left town with fond sensual memories, luggage filled with grass-stained clothes, a new painting and a diminished bank account. Happiness, maybe, too.

To celebrate a sale, Strether booked a few weeks in Mykonos, sunning and cavorting. On his return, he answered the frantic calls from the new collector, explained his absence and assuaged the worry with soothing words. He devoted the next months to carefully distancing himself from the new collector, letting down gently. Then came the decisions about a new painting and the season to come.

Gertrude Branch was a dedicated ally to his cause. Earlier that day we talked on the telephone and she told me, “Donald is a sublimely sensitive person, deserving particular care. His wounds from childhood will never be healed. So sad, so deeply scarred. So damnably attractive.”

I said, “Get off it, Gertrude. Remember, unlike a lot of people we know, I get along with Donald and enjoy the illicit things we do at his lunches.”

“I suspect otherwise. Your face is a blank sometimes. I can’t see what you’re thinking when I look across at you.”

“You, of all people, should respect that,” I said.

“Nonetheless, I understand this new painting is a triumph on its own and just waiting to be placed.”

“And what do we do this time?”

“We’ll see that Donald sells his painting, that’s what. My connections are very valuable for Donald. After all, it was I who introduced him to Paul Farthing and his group and Ambrosia Noad, with her millions.”

I was included at the Farthing luncheon earlier that year, an occasion that late spring which netted Strether a handsome sum. “So who is it in the cross-hairs today?” I asked.

“An important novelist. Twenty weeks on the bestseller list. And, more importantly, he has banking money from his grandfather. He and Donald met at my opera benefit, which you declined, and this luncheon today was concocted on the spot. Yesterday they had a picnic alone on the Big Tesuque and dinner at the Compound. The painting will sell itself.” I could imagine the firm set of Gertrude’s jaw.

“A remarkable painting.”

She was quick to answer. “Is that envy in your tone? Not at all becoming, dear boy.”

“But what about me? Don’t my paintings need your launching ceremonies? A hoist from you now and then could do wonders.” I could not resist testing Gertrude a little although I hated the process of selling a painting myself, much preferring to pay a gallery to act on my behalf.

“Rubbish”, she said, “you would survive in the strongest sea. Quite distinct from Donald, you thrive on adversity.”

“One of your discards would do. Perhaps a minor heiress with blank walls.”

“Stop complaining. You’re lucky to be included.” She hung up the receiver with a bang.

With the connivance of Gertrude and others, Strether disposed of a steady stream of his richly priced gems. There were no bargains in that simple adobe studio. A whole year could be lived upon the proceeds of one sale, including his sojourn in the Greek islands. This year, with the Farthing sale already under his belt in April, Strether just might be in for a double-header.

Mine was the role of the Judas Goat. I had proven valuable on an earlier midday affair when I quite by chance expounded on the Minoan influences of terra cotta and pale blue in Strether’s colors. It clinched a sale that had been dangerously at sea. I saw Gertrude’s eyes narrow as she reassessed my worth upwards. Thereafter I was usually included when another Strether was ready, to lure the new victim forward.

At first blush, I felt guilt at taking part in this charade, but in time, I found a rationale for my actions. The rich of this world are fully able to take care of themselves financially, and perhaps emotionally. It’s the artists of the world who need help.

I later expanded my Minoan touches to include a short lecture on the classical proportions of Strether’s panels, the impeccable quality of his surfaces and the subtle O’Keeffean overtones in his shading. I quite relished these professorial touches. The more shameless the trickery, the more I embraced it.

Today was the debut of another painting. Strether rose early to set things straight with a phone call to tell me about his new piece. He spoke almost in a whisper, every word a special confidence. “I saw a glorious sign in the sky early one morning, three stars in a row and the whole painting appeared in my mind,” he said. Considering that all of his paintings were exactly the same motif, a blue square in the middle of a mottled brownish rectangle, it was no great feat to have it appear fully clothed in the mind. I asked him to describe it.

“A blue doorway in an earthen wall. Colors and composition had already been worked out, as if from on high. The blue of opportunity, a new life and the earthen colors of the status quo. I saw the exact texture on the linen.”

I knew this celestial assistance would become a major theme at dinner parties. “As our friend, Mozart. Whole symphonies downloaded like so much email?”

“You’re making fun of me now. But it really happened.”

I felt my nose for growth as I said, “I’m sorry. I can’t wait to see it.”

Strether said, “There are new ideas in this piece. The stars in the doorway.”

The stars were definitely something new and this was his calculated way of letting me know that the stars would be the subjects of my dissertation after lunch. If I lectured convincingly on their stunning originality, I could pay for my lunch and continue to be a member of the Strether cabal.

“Stars. How exciting.”

“Think about it,” he said. “We’ll gather at twelve.” He rang off.

Strether had no sense of humor at all and I always felt bad after I flung a bit of sarcasm his way. He was strangely without the usual defenses. Furthermore, he was dishonest only on the large matters, while maintaining scrupulous uprightness on all the other, smaller issues. It confused me that a thousand small blessings could make up for one major crime. What exactly was the meaning of moral turpitude and was Strether born without it, arriving in this world with a chromosome missing? Did luring the gullible rich into parting with some of their hoard really constitute a sin?

As long as I proved a capable shill, I would be included in future lunches and I would be given moneyed contacts to exploit later on my own, after the Strether purchase was safely in the bag. I repeated in my mind what I remembered about Orion and Betelgeuse and the mid-winter meteorite showers as I parked the car below his house.

Strether’s house was simple and classic, without modern heat and only rudimentary electrical outlets and plumbing. Its high, elegant windows gave a full view of a pristine valley below. The multi-paned windows were recycled from the Sisters of Loretto School razed for downtown development and the walls were surfaced in authentic mud plaster. In the courtyard was an ancient juniper, a remnant of the primordial tree cover of the area. Lunch was set in its shade at a pine table with pottery and glassware from Mexico, Georgian silver forks and cotton napkins.

Indoors, I could see that the others were there already: the novelist, Gertrude and Strether, who was pouring white wine from a pitcher into more Mexican glassware. The novelist saw me first and smiled a welcome.

“So much talent at a small luncheon. How delicious,” he said.

“It’s good to see you again. Isn’t this a wonderful house?” I said.

Before he could answer, Gertrude sensed something amiss, information not given to her. She said, “What’s this? I hadn’t realized you knew one another.”

“When you said novelist I didn’t know you meant Willard Chivers here. We met last week at the Halcyon Gallery.” I patted Willard on the arm, while Strether disappeared into the kitchen.

Gertrude was not satisfied, however, staring pointedly at me. She was a short, heavy woman with costly processed hair a color somewhere between rosé wine and straw. When required to, as she did then, she could pull together the ranging parts of her frame into stiff uprightness, a definitive version of social outrage. “Indeed. Are there suddenly dozens of novelists in town? A literary convention, perhaps?”

Since Gertrude’s thrust required a parry, I thought over what my answer would be. Willard and I had met the week before at the opening night gallery reception for a young landscape painter. There was a crush at the bar and we bumped elbows as we reached for the same plastic cup of wine. He laughed and I noticed he had straight white teeth. Expensive teeth. He was a slim man, aging well, with bright blue, friendly eyes. He had the long narrow frame of an ascetic monk from Athos.

We talked a bit and I told him that I was a painter, too. I invited him to go see what remained of my one-person show at the Ludlow Gallery. “The reviewer in The New Mexican termed me a ‘Minor Mannerist Landscapist, worth watching,’” I said. I thought that was a humorous comment and I saw him smile, too, as he wrote down the address of the Ludlow Gallery. We parted ways when friends of his arrived to take him to dinner.

Gertrude, who seldom gave benefit of a doubt to anyone, suspected something other than this innocent encounter. Her bright eyes stayed on my face as I formed an answer for her.

Mercifully, Willard interrupted with, “No matter, it’s too nice to loiter inside. Let’s go to the terrace.” He took Gertrude’s ample arm with “My dear” and propelled her through the French doors. He had expertly cut short her questions for the moment. “Donald says you terrorized the Red Cross in Paris during the war. Tell me all.”

Nodding and smiling at Gertrude’s oft-repeated tale, Willard showed his patience and kindness. The hardship of war, particularly her own, was her favorite subject and she carried on until we were seated at table. Lunch was a cold poached salmon, a large bowl of salad greens from the patch Strether grew out back, a peasant loaf and Spanish white wine in the Mexican glasses. Apple tart and espresso followed.

On the surface, Strether’s persona was that of a simple, ethical man of the arts. He eschewed chemical pigments in his work. He was concerned with the encouragement of traditional adobe architecture and was a keen proponent of solar design, heating his house only with a wood stove. He gardened to have organic vegetables for his guests, and he entertained simply but with style. Small but annual contributions arrived in his name at the opera and chamber music festival. Was it so terrible that he bilked the rich with his questionable paintings? If the well to do were foolish enough to fall into his ethical and aesthetic traps, was he so bad?

There was a pause in the conversation as we finished the coffee. Gertrude, in whose presence lapses of prandial chatter were forbidden, took the opportunity to start the real proceedings. She put her heavily ringed hand on top of Strether’s, long-fingered and thin. “And now, what treat awaits us in the studio, my dear? I have several yawning blank walls since the museum people came to wrest away my gifts, the Gaspards.”

She ably played the coquettish game that she just might buy the painting herself. It was intended to put the victim off his guard and make him feel comfortable, unsuspecting in the company of peers. I wondered if Willard was fooled by our provincial games. Didn’t he sense the glowing red dot on his forehead?

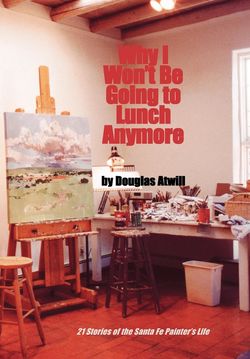

We gathered up our glasses and walked slowly along the path to the separate adobe studio. It was one large room with north-facing windows and a high ceiling. The painting was under a white cotton cover on the easel, encased in the shaft of bright sun from the skylight. Strether seated Gertrude in the one chair, a regal Spanish design with gilded finials, and motioned the two of us to the long window-seat with cushions.

He then pulled off the cover with a flourish. He said nothing as we stared at the small canvas, which was even more austere and plain than I anticipated. There was, as expected, a row of three stars high in the cerulean blue doorway. The background was an expertly applied wash of earthy light terra cotta.

Willard, always polite and well-bred, started with, “How elegant, Donald. It’s most impressive.” He was not showing any of his cards at this time.

Gertrude made a humming sound while she gave her well-practiced expression for viewing serious art. I thought of an old, blonde iguana on a limb, blinking.

It was time to get my part started. “Stars in the doorway, Donald. What can they mean?” Did I sound as if I was reading from a script?

Strether replied in his softest tones, “I never put into words what all can see. The painter should paint and let the image speak for itself, others can do the talking and writing.”

“Quite so. Well, the stars must imply a new day or a change coming in the heavens. A spring apocalypse, perhaps?”

“I couldn’t say.”

So, I jumped into my discourse about the blinding of Orion and the stormy weather that attended him. Clearly, it was Arthur Dove and the Modernists, rather than Matisse or Bonnard, who were the forebears for this painting. The breaking of images into related shapes and planes was the key to this canvas. More down this avenue and it seemed as if I had just got going when I saw Gertrude scowl and Willard force down a yawn. This was not going to be an easy sell.

Strether, however, appeared to be in another world, nodding now and then in enjoyment of my monologue. Both Gertrude and Willard looked glassed over. So I continued, directing my comments to the only one paying attention.

“Your surfaces, Donald, are becoming even more refined, more splendid as your compositions get more spare. The Shaker quality of simple refinement.”

Strether clearly looked pleased. I went on for a few minutes more, then wrapped it all up with, “What do you think, Willard?”

He wore an inscrutably polite expression, revealing nothing. He knew, however, that some sort of reply was expected. “I would buy it in a snap, Donald, as it is a lovely change of direction from the others I have seen in the fine houses all over town. All, I might add, to be coveted.

“But . . . ” he said. Gertrude’s eyes sprung back to life. “I just this morning bought three Mannerist landscapes at the Ludlow Gallery. I had been looking at them since my friend here sent me there last week and I could not decide among them. I wanted them all. So now, all three are being shipped to my new house in Sag Harbor. And that exhausts the art budget for this summer.”

Strether said, “I see.” He and Gertrude looked at me with matching blank expressions. A silence followed, ended only when Gertrude maneuvered herself up from her Spanish throne and thanked Strether profusely for lunch. He accompanied us all down the hill to the car park.

Gertrude between breaths pumped out platitudes about what a town for art Santa Fe was and what a coincidence that Willard chose my small paintings. She would have given me her narrow-eyed look of disapproval if the path had been smoother. It was an awkward end for the occasion, in spite of hugs and goodbyes all around. Strether remained silent as we embraced without warmth and studiously avoided looking at me again. I was sure I would never be included in another lunch at Strether’s.

For the rest of the day I had mixed feelings about how events appeared to tarnish my good name, albeit a conspirator’s good name. I was now indelibly the traitor and the ingrate. Should I have insisted that Willard return my paintings so he could buy Strether’s? Was there something I could have done to set things right? I slept restlessly that night: the sleep of the unjustly blamed, the sleep of the newly unfrocked.

As one door closed, another cracked open ever so slightly. When Gertrude called me the next day, it was apparent that the Strether lunch had wrought a subtle change in the murky currents of Santa Fe art. She had quickly sensed these small but important rearrangements, which now had me recast in a somewhat more elevated position.

“What a bore that Willard fellow was. Mind you, I am relieved you snagged something out of it all. Despite poor Donald. The Ludlow Gallery is fortunate to have you.” She paused a moment to consider the unfolding events. “We must have lunch next week with Ambrosia. She’s back in town for the rest of the summer and needs a project. You, I think.” As the mechanics of art purchasing in polite society shifted ever so slightly, Gertrude was not going to be left stranded alone with Strether on an unpopular peninsula.