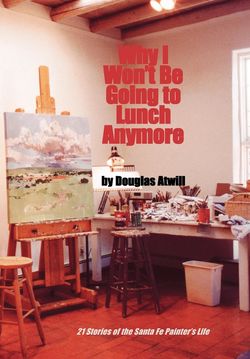

Читать книгу Why I Won't Be Going To Lunch Anymore - Douglas Atwill - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Supine Pueblo Maidens

ОглавлениеIt should have been a festive day, this St. Valentine’s Day, but instead it was a gloomy, cold one with snow starting at first light and continuing in a steady descent throughout the morning. Magnus Morrison saw only two people go by the window of his Canyon Road gallery for the past three hours. There had been one sale so far this month, a small drawing of Flanders poppies framed in silver gilt. Morrison thought this was going to be a lean year for the painters of Santa Fe and he was glad to have a little saved from the summer months.

For the preceding two hundred years the adobe house that held the Morrison Studio Gallery had been a modest residence, housing a family of woodcutters. When Santa Fe started to grow, they moved away to a mountain village where the rest of their extended family lived and they leased the house to Morrison with the understanding that he tend the apple trees behind the house. He painted happily in the back rooms opening onto the orchard and set up the front room as a gallery for his own work. A generous window allowed passing tourists to peek in and decide if the Morrison product was worth a visit.

In the summer months, tourists often did visit his gallery. He was compelled to hire an assistant to sit the space while he painted new work in the back room. Otherwise he would have no time to paint at all.

She was a Miss Harkness, who lived in a one-room apartment in the hacienda down the street and saw Morrison’s sign in the window. She gave him a persuasive presentation speech on why he would benefit both financially and mentally from her employ. Her qualifications to sell paintings included two years study at the Philadelphia Museum School in the 1930s and a lifelong love for art in general, with emphasis on the Fauves and the Post-Impressionists. She had worked for years in Philadelphia to separate department store customers from their money in Ladies’ Scents and her commanding height made prospective buyers pay attention.

Morrison was immediately convinced of her worth and it was now the third winter of their time together. He had come to a grateful appreciation of her talents for converting his canvases and drawings into ready cash. From May through November she came each afternoon to tend the Morrison Studio Gallery, giving his enterprise an air of quality and distinction. No other studio galleries on the road had a near full-time employee, staff usually consisting of the artist himself or his spouse. If Santa Fe afforded a livelihood for painters, it gave Morrison a better one than most, not ignoring the excellence of his work.

Winters brought commerce to a trickle but not to a complete standstill. In the colder months Morrison often had a few nice sales and he kept Miss Harkness on two afternoons a week just to catch those few. This February day was one of her scheduled days even though good sense said to close until after the storm. Morrison thought it mean-spirited and penurious to deprive her of the opportunity to make her commission because of a natural event, snowfall.

She arrived promptly at one in the afternoon, stooped under the low front door jamb and made the cascade of harness bells hanging on the door come to life.

“Good afternoon, Magnus. What a glorious gale we’re having, a fury from the white heart of the Arctic itself.”

Of an age between old and elderly, Miss Harkness was straight-backed and thin, with a hairdo seldom seen west of the Mississippi in those years, an overstated Marcel of henna red. In this community where personal appearance mattered little to most of the artists, she looked like an exotic crane blown out of her own breeding grounds by global winds. She believed in dressing warmly, for even in summer a chill lurked to diminish her health. Today she was enveloped in great swards of persimmon wool garments and oxford shoes of burgundy leather. Her departure from the Philadelphia department store included a lifetime supply of designer scarves, which she used in stylish variety.

Morrison said, “I thought of calling you to stay in. Not a chance of a sale today, I’m afraid, Miss Harkness, but since you’re here. . . .”

“Nonsense, Magnus, cultured people of means go out in all weather.”

She dusted the snow off her cape, scarf and tam and folded them for the coat cupboard. Adjusting her dress with a few pulls and smoothing her collar, she was ready to take the helm of their little ship.

Morrison was not convinced by her cheerful assessment of the day’s catch. “The only two that struggled by this morning looked unpromising, even though they peered for a long time at my Evening Light on the Sangres scene through the window.”

“I’m sure that an exceptional and moneyed collector or two will find our door and we’ll finish the day with a noteworthy sale. I’ll make a fire to cheer things up.”

“Good idea.”

Morrison turned to leave, but Miss Harkness was not done. “What if I just rearrange a bit, perhaps put a Pueblo maiden in the window?”

“Fine, fine, I’ll just be in the studio.” He went into the back room and closed the door. He had learned never to leave the studio door open, as visitors to the gallery invariably were drawn to invade his workspace. Particularly women wanted to come in and see, and they frequently left an aura that cut right across whatever he was working on. Magnus claimed to be sensitive to an atmosphere left by others in his studio. It could ruin an entire morning of painting.

Miss Harkness busied herself dusting the paintings on the wall as the corner fireplace took hold. She went to the small closet that held the racks of undisplayed paintings and pulled out the next to last painting of a Pueblo maiden. It was a small painting framed with a rococo gold fillet. A young Nambé Pueblo girl lay nude on a striped blanket, baskets and corn clusters filled the outer corners of the composition. Her flat, imperious gaze was as bold as Manet’s Olympia among the savages.

The choice of the Pueblo maiden was an open indication that Miss Harkness, despite her façade of optimism, thought today was going to be difficult. The maidens invariably were well received and would sell out completely if displayed one after another. Miss Harkness devised a scheme to squirrel away the maidens for difficult times, an insurance policy to be rationed out only on the slowest of days. However, the supply was dwindling.

Morrison had never actually seen a Nambé Pueblo maiden. On hot nights one summer the motif kept appearing in his mind, a lithe young woman resting on a red and white striped blanket in diverse poses. His favorite version included the supine maiden with a tablita headdress in her hand, connoting that she had only just a moment before disrobed. Somehow, the impression that she had been loitering there without clothes was not so appealing.

He made no progress in converting his idea into actual paintings, but it took on a nagging intensity in his thoughts. He calculated the girl’s body proportions, making her slightly shorter than art-school guidelines of seven heads tall. Her body weight crept up until he had fixed the vision as an enticing, nubile girl, surrounded by the Indian artifacts he knew from museums and local shops.

Sunlight from the small pueblo window made a line across the canvas in his mind, up and over her body in a golden-white stream. In the final version of his fantasy he included a section of the window itself, with a darkness that caused an indentation in the shadow. Could that suggest that a tribal elder peered in on this unsuspecting youngster? The painting only awaited a model for his work.

Then at lunch one day he saw a young woman sitting alone at an adjoining table who closely matched his mental image. Her body was ripe like a plum, her stove-black hair cut in straight bangs and in a single horizontal line around her neck. She was stocky but not yet fat, her chubby wrists encircled in silver bracelets. He almost saw the marks of the tablita on her dark hair. He could not avert his eyes and after a while he realized his stare had caused her discomfort.

Morrison leaned over and asked her quietly, “You aren’t by any chance from Nambé Pueblo?”

“Of course not. I’m Polish, from Brooklyn.”

“You quite favor the Nambés, you know, your hair and your size,” he said.

“They live north of here?”

“Indeed. I’m a painter, my studio just down the street. If you had the time and the inclination, would you pose as a Nambé Indian for me?”

“Without clothes?”

“Yes.”

“No funny business?”

“No funny business, I assure. I could pay you well.”

“Okay, I’m almost broke.”

That was several summers ago, before Morrison hired Miss Harkness. The woman, named Milla, came afternoons to his studio to pose in the set-up he had arranged by the window. Sunlight streamed in by mid-afternoon and the fixated shapes in his daydream version merged with the real scene in front of him. He was transported to a woman’s chamber in the pueblo for several hours until the light changed.

In a creative passion, he painted canvas after canvas, each a variation on his theme and he scratched out numerous sketches of the scene. He now remembered the time fondly as a sensual feast, not so much of Milla herself but of the pueblo image that she stood for. She was a messenger, an icon to be valued for what she symbolized rather than what she was.

They took their breaks away from the easel in the deep green shade of the orchard. After initial awkward tries at conversation, they both came to an ease sitting in silence under the trees. In summer months that followed, the scent of fallen green apples brought it all back to Morrison.

By the end of August he had a dozen of the pictures finished and several in various stages of completion. Milla planned to leave in September and Morrison asked her to stay on for a while. He suspected at the time that this was his finest hour, that he would never paint this well again. She left, nonetheless. The combination of hand, heart and mind had fused to give him a group of magical paintings as none before.

When he started to display them in his gallery space, Morrison saw the paintings go one after another, usually sold soon after they were displayed. All the framed sketches sold in the first autumn. His interest moved along to other motifs, landscapes of the mountains nearby and gardens from his neighbors’ courtyards. These were subjects that took longer to sell and Morrison felt challenged to make them as attractive to buyers as he could, but they never matched the popularity of the maidens.

Miss Harkness dusted off the next to the last maiden. After centering the canvas on the easel at the window, she adjusted the spotlight to a small focus. Reaching just outside the front door to a pinon pine there, she pulled off a needled branch to adorn the top of the painting. She thought the twig gave emphasis to the archaic nature of the scene and added poignancy to its presentation. From her days in Philadelphia, she knew the importance of display. The pinon’s branches nearest the door were almost picked clean.

The snow outside had shifted from a fine white dust to large wet coins falling with deliberate slowness, sticking on every surface. By three in the afternoon darkness was winning and the few automobiles that drove by had their headlights on.

Morrison at his easel heard the bells, followed by voices in the gallery, but only Miss Harkness’s words were understandable behind the closed door. Sharp syllabic definition was one of her small vanities, but even then only part of the exchange was clear.

“ . . . such a canvas is a life-long (something) . . . both the Metropolitan and the Art Institute insisted that . . . (something) (something) . . . Impeccable taste. . . . The lovely skin tones as only an ethnic Tewa woman. . . .” And then a very long silence. The bells on the door indicated a hasty departure.

Morrison was sure that no sale had been consummated. He painted on, refining the stems and leaves of a large garden painting, a motif he reserved to keep his spirits up on gloomy winter days. He heard the bells on the door again.

Another visitor to the gallery could mean that Miss Harkness’ assessment might be right. This time he heard nothing of the conversation, and he lost interest in eavesdropping and returned to the details of a complicated umbel of yellow bloom.

He worked on for half an hour more and quite forgot the matters of commerce in the front room. Miss Harkness’s knock on his studio door startled him. How was it that she could knock so much louder than men?

“Come,” he said.

“Magnus, can you visit with some sweet people from Indiana, the Piersons? I’m sure you’ll want to meet them,” she said.

The term “sweet people” was their code word for “buyers,” usually very substantial buyers. In this way, Miss Harkness could interrupt Morrison in the studio by saying he must meet some sweet people from Portland or Houston and this meant they had already bought a painting. Buyers of smaller paintings were referred to as “interesting people.” People only considering a purchase, needing heavy encouragement, were called “charming people.” Morrison could then judge just how much time to waste in pleasantries.

The Pierson couple came in behind Miss Harkness, peering around the studio with obvious delight. Morrison’s work place held many tableaus and props to interest collectors: baskets and pots, feathered head-dresses, war shields, dried floral arrangements, and a long row of coat-hooks with Indian costumes.

Mrs. Pierson spoke first. “Mr. Morrison, we love your work. Especially the Nambé Pueblo pieces.”

“Call me Magnus, please.” He took Mrs. Pierson’s hand, smiling. “How nice of you.”

Miss Harkness interceded, “The Piersons had the discerning taste to buy the very last pair of your Pueblo maidens. They will join the rest of the Pierson Collection at the Art Museum in McPherson, Indiana.”

Miss Harkness’ face betrayed nothing of her feelings. “The Piersons would like to organize a museum exhibit of your work next winter in McPherson. The museum would pay for everything and you could stay right with the Piersons.”

Mrs. Pierson said, “Herbert and I have been collecting in New Mexico since the Thirties. We have Maria pots, Gaspards, Sharps, Ufers and all the right artists of Taos and Santa Fe. Our small Victor Higgins may be his very best and we’re hoping to bag a John Sloan view of the cathedral. You would be in good company, we can assure you.”

What a horrible idea, Morrison thought. “Thanks, so much. Give me time to think about it.”

“Of course, Magnus. Give it your earnest consideration. We sponsor these exhibits every few years to share our new purchases with the people of Indiana. We’ll be at La Fonda Hotel for the rest of the week,” Mrs. Pierson said. Already Morrison was regretting giving permission to use his first name.

“I’ll be in touch soon.”

Miss Harkness wrapped the two small paintings in several layers of brown paper and the Piersons departed into the swirling storm, heading farther up Canyon Road to other studios and galleries. Morrison wondered who else would be included in the Pierson collection this day.

“I object, Miss Harkness, to being something people from Indiana want to ‘bag,’ like a ten-pointed elk or a champion-sized zebra,” Morrison said.

“Quite right, Magnus. I gave them no encouragement at all in what your answer might be. You must turn them down completely.”

“Good, because that’s exactly what I am going to do.”

“Mrs. Pierson seems to be the guiding light at the museum. It must be a very small, very provincial museum, but whatever she wants, they do, she told me.”

“Women like her use the museum to add luster and value to their own collections. It’s totally a matter of dollars, despite how much she throws around the compliments. Deposit the check tomorrow, will you please, Miss Harkness. Then, we’ll say no.”

“Yes, Magnus.” Miss Harkness turned off the lights and put the “Closed” sign in the window. She walked away into the dark afternoon.

The snow continued for several more days. In the quiet gallery Morrison thought about the sale of the last two of the Nambé paintings. Surely, there was one of those incomplete versions in his racks, one he could supply with final changes to add one more to the series. He went to search for it but with no success. Then he recalled using those canvases for another, more favored motif, painting over Milla’s legs or arms with thick loads of gesso.

How had he not saved one or two of his best paintings from the past years? Why was it so important to sell the work that came from that high plateau of his painting years? Now they were all dispersed to places like California and North Carolina, the last two now in the hands of those Piersons from Indiana. Why was earning the dollar so necessary that he brought upon himself this sense of loss?

He should have called Miss Harkness, after all, giving her the day off. He knew that he could never rekindle the flame of excitement and skill of those summer afternoons by the orchard with Milla. Now, they were a just remote memory under the falling snow.