Читать книгу Yellowbone - Ekow Duker - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 6

ОглавлениеAfter the violin lesson with Mrs Harrison, André did not go home straight away. He drove until he had left Mthatha behind and the land began to lift and fold itself into a crumple of green hills. He guided his mother’s car off the road and parked on the bank of a small river. He sat in the car clutching the steering wheel as if he dared not let it go. As always, the sight of the angels had filled him with delight. He had seen them too often to be afraid but he still shivered with the sheer wonder of it all.

He sat in the car until the sun was high in the sky and the reflection of the trees in the water took on a silvery hue. It grew warm. He unbuttoned his shirt, and then took it off altogether. Then, with a shyness as if someone were watching him, he reached for his violin and stepped out of the car.

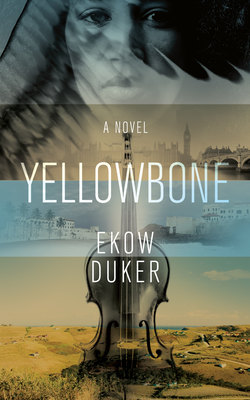

At first he played with great care and tenderness, as if that would coax the angels back. He’d give his life to see them again. He played the same piece he’d played for Mrs Harrison, Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto in D major. The notes he played mingled with the soft gurgle of the water and together they caressed him, teasing and soothing his senses. But the angels did not return and André’s passion grew dark and intense. Why wouldn’t they come? With a wild cry, he flung the notes into the treetops. The birds scattered and fled from him in screeching clouds of black confetti. Enraged, André hurled the violin away from him and fell to his knees on the river bank. He put his face in his hands and began to weep.

It was late afternoon by the time he got home. He was hardly out of the car before his mother was upon him.

‘André!’ Marietjie cried, her voice shrill with anxiety. ‘Where have you been? Mrs Harrison said you left her house hours ago!’

‘I went for a drive.’

‘A drive? By yourself?’

‘Who else would I go with? I went for a drive, that’s all.’ He busied himself with his violin case and the music stand and the leather briefcase that contained his sheet music.

‘I was worried about you.’

‘Why? No one bothers us here. That’s what you always say, don’t you?’

She ran across and blocked his path. She stared at him for several seconds, her eyes searching his face. Then she gasped and seized him by the arms.

‘You saw them,’ she whispered. ‘Jy het die engele weer gesien.’

‘Not now, Ma. Please – not now.’

But she held onto André and would not let him enter the house.

‘I’ll call Doctor Viljoen right now! He said to call him if you ever saw them again.’

‘They’re gone,’ André replied with exaggerated tiredness. ‘There’s nothing Doctor Viljoen can do.’

‘At least he gave you medicine.’ She looked at him suspiciously. ‘You’re still taking his tablets, aren’t you?’

‘I threw them away.’

Marietjie’s face fell. ‘Oh, André!’ she exclaimed. ‘You know what happens to you when you don’t …’

‘When I don’t what, Ma?’ he interrupted her rudely. ‘Doctor Viljoen is nothing more than a quack. The pills he prescribed were shit. They made me so sleepy I couldn’t play anything properly.’

‘At least they kept the engele away.’

‘But I don’t want them to stay away!’ André roared. When he saw his mother’s face twist in fear, he grew suddenly embarrassed. He knelt and spoke to her in a more gentle tone. ‘I’m not sick, Ma, and I don’t need medication. And certainly not from Doctor Viljoen.’

‘At least he gave us answers,’ his mother said stubbornly.

‘No, he didn’t. Everything he told us he read up on the internet. I could have done that myself.’

‘But he’s a doctor!’ his mother cried.

‘He’s a paediatrician, Ma, not a neurologist. He should stick to diagnosing babies with colic and nappy rash.’

He stood up and walked into the house. Marietjie followed him, chirping like a small bird in distress. They said little to each other over dinner and just passed the dishes back and forth in silence.

‘This can’t go on much longer,’ André said quietly.

‘What do you mean, André?’ His mother’s eyes were dark with worry.

‘Let’s forget about the engele for a moment.’

His mother was poised to interject but André held up his hand to stop her.

‘Today I gave violin lessons to a woman with no talent,’ he said. ‘And on my way home I stopped to play in an empty field with nothing but trees and birds around me. Don’t you think I can do better than that?’

‘There are weddings,’ Marietjie said, the desperation evident in her voice. ‘It’s the in-thing these days to have a violinist at a wedding. You could play at weddings!’

‘Really, Ma? You’d have me spend my life playing some bitchy bride’s favourite pop song? There aren’t that many weddings around here anyway and even if there were, I doubt most people could pay. I told you we should go to Joburg or Cape Town, but you insisted on bringing us here. To Mthatha.’ He flung his arm in the air to encompass the small, tidy kitchen and the flat-pack wooden furniture. ‘I’m serious, Ma. I can’t go on like this.’

The light went out of Marietjie’s eyes and when she spoke, her voice was as small as a little girl’s. ‘You’re leaving me then.’

André gave a quick nod. ‘Will you go back to Bloem?’

His mother looked away from him. Her lips trembled as she gulped a mouthful of air and then another. It was as if she’d fallen off the side of a boat and was struggling to stay afloat. ‘I think I’ll just stay where I am,’ she said at last.

‘But you don’t know anyone here.’

She shrugged, much as André might have done. ‘It’s quiet, André. I like that. No crowds jostling you in the mall. No one climbing over your wall at night to hit you over the head. No agricultural shows with so much cow shit the stench stays in your nose for days.’ She took a deep breath then went on. ‘They only invited me to those places because I was Mrs Trevor Barnes.’ She enunciated the name slowly and with as much scorn as she could muster. ‘At least in Mthatha I can be myself.’

André reached across the small table and covered his mother’s hand with his.

‘There’s another reason I need to go,’ he said softly. ‘You need to stop fighting my battles for me, Ma. I can look after myself.’

Marietjie dabbed at her eyes, not caring that she might be ruining her makeup and leaving dark smudges on her cheeks.

‘They’re not like us, you know,’ she said.

‘Who?’

‘The English.’

André sighed. His mother had a factory-set resentment towards the English. It was like she forgot her son was half-English.

‘The Harrisons are all right,’ he said brightly. ‘They’re English. I’ve never met Mrs Harrison’s husband Bill, but Claire has always been very kind to me.’

‘I don’t mean the Harrisons. I’m talking about the English English,’ his mother said. She gave a heavy sigh. ‘But you’ve set your heart on going to London, haven’t you?’

André avoided her gaze. ‘I’ve not decided yet,’ he said.

She looked at him and while her mouth was firm, her eyes were glassy with tears. ‘You don’t have to lie, André. You made up your mind a long time ago.’