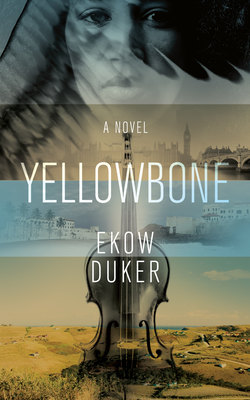

Читать книгу Yellowbone - Ekow Duker - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 12

ОглавлениеIt began to rain as André ran to his car. As he drove off, large raindrops dashed themselves against the windscreen and slithered down the glass. It grew chilly inside the car and his hands tightened on the steering wheel. Elias. He remembered Mrs Frederiks, his nursery school teacher. And how she leaned over him every morning, her breasts pressed against his back and her hand cupped protectively over his.

‘Let’s count out the horizontal lines together, Elias. One. Two. Very good. Now the last one. Just one more, Elias. One more.’

But before Mrs Frederiks could step back and say, ‘Well done,’ he’d have added a raft of extra lines to the first letter of his name until his capital E looked like a small comb standing on end. He never understood why Mrs Frederiks took it so badly. He got all the other letters right, didn’t he? But every time he caricatured a capital E and couldn’t spell out his own name, red blotches would appear on Mrs Frederiks’ cheeks and her nostrils would dilate in the most alarming manner. Humiliated, he’d sit on his little stool and try not to listen to the rest of the class shrieking and hooting with laughter. They laughed so hard you’d think Maria Snyman had shat her pants again.

‘Mr Barnes, we really need to do something about Elias,’ Mrs Frederiks declared to André’s father one afternoon. She’d seen him drive in and had run outside to waylay him in the carpark. She had her hand on the window sill to stop him from rolling up the glass.

André’s father bared his teeth and growled at her. ‘I’m in a hurry, young lady.’

Mrs Frederiks sighed with exasperation. ‘That’s the problem, Mr Barnes. You’re always in a hurry. I’m sorry to say this but neither you nor Elias’s mother appears to take the slightest interest in his development.’

She leaned into the car and waved André’s work under his father’s nose. The sheets of paper crackled loudly and André, who was standing behind her, wished he could run away and hide.

His father’s face darkened and he looked up at Mrs Frederiks with a sneer. He hadn’t been elected to the city council then.

‘Why don’t you just fuck off and leave us alone?’

Mrs Frederiks drew up in shock. She stumbled backwards into André, battering his head with her bottom. She smelled of freshly washed linen and something else he couldn’t quite place but remembered as oddly pleasant.

Defiantly, Mr Barnes revved the car engine. He’d bought the Toyota a few months ago and it was the only model of its type in Bloemfontein. André stood rooted to the spot. He didn’t know whether he was meant to go with his father or stay there with Mrs Fredericks. Then his father leaned out of the window and roared at him.

‘Come on, boy!’

He was climbing into the Toyota when the car lurched forward with a loud squeal of rubber. His father slammed on the brakes and André tumbled into the well behind the front seat. He was still upside down and trying to right himself when his father swore at Mrs Frederiks again.

‘If he can’t get “Elias” right, you can call him what you bloody well like! Call him André, for all I care.’

It had been as simple as that. He was hardly ever called Elias again. Not until that night in the chapel in Bloemfontein. Not until Father Majola. Not until tonight.

Elias.

Angel boy.

It was raining heavily now and the windscreen wipers thudded vainly from side to side. He wanted to stop right where he was and get out of the car with his violin and play. He didn’t care that there was a storm raging around him and that the water would ruin the instrument. He pounded his fist against the steering wheel and moaned out loud. What was it Father Majola had said? That he was doubly blessed? Well, he was wrong. He wasn’t doubly blessed, he’d been cursed twice over.

The first time the angels appeared, André was ten years old. He’d caught a slight fever and his mother had decided he must stay in bed and not go to school. His father had left for work already and by a curious sleight of physics, Trevor Barnes’ absence filled the house with light. The sounds of his mother tidying the house drifted up to André, a chattering of cutlery and the soft clapping of wooden drawers as they opened and closed. The radio in the scullery was tuned to classical music, an indulgence for his mother when his father was not at home. He thought the gushing of water from the kitchen tap was like intermittent bursts of applause.

All of a sudden, André heard a sharp knocking outside his window. He glanced up but no one was there. Just the crooked branches of the olive tree swaying in the wind. He pulled the bedclothes over his head and lay down to sleep when he heard it once more.

Rat-tat-tat.

‘Come in,’ André said in a small voice.

The knocking stopped and André felt a tingle of excitement as he watched the window. He half-expected it to open but it stayed firmly shut. ‘I must be imagining things,’ he muttered to himself after a few minutes. He was settling back into the pillows when a powerful downbeat of air swept past his head.

He should have been afraid, but strangely enough, he wasn’t. There were three angels that day, with wings so large they shouldn’t have been able to fit into the small bedroom. But somehow the walls seemed to move apart and gave André the sense of unlimited space. The angels had been more playful then. They swooped around André’s bed and turned cartwheels in the air, chasing each other in a perpetual game of catch.

André reached out his hands and tried to touch them but they stayed tantalisingly out of reach. Then the radio in the kitchen switched to an advertisement about car tyres and just as suddenly as they had come, the angels plunged through the window and were gone.

They came every day until André got better and he couldn’t make excuses to stay in bed anymore. His mother had to drag him out of his room because he would have given anything to stay at home.

‘But the engele!’ André wailed.

‘Be quiet!’ his mother snapped. She glanced warily over her shoulder. ‘I told you already. Your father won’t like to hear you talk like that.’

‘But I saw them! They were right here!’

Marietjie gave her son a conciliatory kiss on the top of his head. ‘Now hurry up or you’ll be late for school. I’m sure the engele will be here when you get back.’

She stood at the door and watched him go. When he glanced back, he caught in her drawn, anxious face something in her expression akin to fear. He waved at her and she quickly pulled her features into a nervous smile. When he’d tried to tell her that the things he’d seen were kind and gentle beings, she’d said: Of course; after all, weren’t children little angels too? Then he went on to say that the engele touched each other. And at first she’d thought he meant they made the sign of the cross on each other’s foreheads. But when he went on to explain in innocent detail what the engele actually did to each other, she clamped a hand over her son’s mouth.

‘André!’ she gasped in horror. ‘Promise me you’ll never say those words again! Do you hear me?’

It didn’t take long for André to make the connection between the angels and classical music. They seemed to be especially fond of stringed instruments. He borrowed his mother’s portable CD player and took it with him wherever he went. She only had the one disc, Mendelssohn’s violin concerto in E minor. He sat by himself and played it over and over again while scanning the horizon like a ship’s captain searching for land.

One evening when his father came home, he was more pensive than usual. His silence cast such a pall over their family that neither Marietjie nor André could bring themselves to eat.

They’d gone and given his job to a kaffir, Trevor Barnes said. André was not so shocked at the news. After all, they’d heard the ANC threaten to do that so often on the radio that all the boys at school believed it would happen eventually. It was his mother he felt sorry for. The thought of his father at home all day, seven days a week, would be enough to make her ill.

‘What will you do?’ his mother asked. She had gone very white and the tendons stood taut along her neck.

‘It’s not for a few months yet,’ Trevor Barnes said. ‘I’ve got one or two things lined up.’

He wiped his mouth, then his head with its lacquered cap of dark black hair snapped towards André. His eyes were hard with dislike.

‘André?’

‘Pa?’

‘Why do you keep playing that poofters’ music?’

‘Pa?’

‘Don’t pretend you don’t know what I’m talking about! Mr Botha, your headmaster, called me today. People are talking about you, André. They say you’re behaving like a bloody lunatic.’

Things galloped downhill after that. If his father was going to call him a poofter and a moffie, then he’d play a moffie’s instrument. Just to piss him off. And if he were lucky, the engele just might come back. His father wanted him to play rugby but he detested it. The cold, the mud, the locker room banter, he hated everything about it. They always put him out on the wing, with instructions to ‘Just run’. He hated that. It made him feel like a kaffir running for his life with a pack of heavy white boys panting close behind.

He gained weight in a subconscious effort to get out of playing sports at the hoërskool. In time, ‘Just give the ball to Barnes, he’s quick’, became ‘Don’t give the ball to Barnes, he’s a fat cunt.’ And as André’s girth increased, so did his father’s disdain. And in response, André played the violin with even more diligence and fervour. He discovered he had a natural facility for the instrument. He struggled with Afrikaans and English because of his dyslexia but to the specialist’s surprise, he could read and write music effortlessly.

Try as he might, however, the engele came less and less frequently and their absence caused André great distress. He began to suspect that they only came on those occasions when he played particularly well or played a piece of rare beauty. But when the engele did appear, the sheer ecstasy of their presence made up for the tortured longing that had gone before.

It was still raining when André drove into their yard. He spun the wheels of the car and sent a shower of water and gravel clattering against the side of the house. His mother was standing on the porch, a small, porcelain statue with a furled umbrella at the ready. By the time he’d switched off the engine and looked up, she was right outside the car, the edges of her form blurred and undulating with the rivulets of rain. Mother and son looked at each other for what seemed like several minutes. Then Marietjie’s shoulders sagged heavily and she turned and went back into the house.