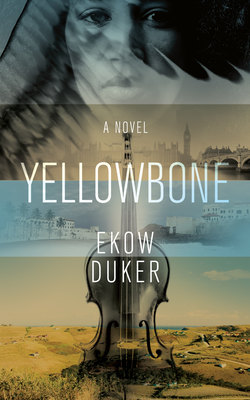

Читать книгу Yellowbone - Ekow Duker - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 4

ОглавлениеMrs Harrison was indeed waiting when André arrived. She was a weather-beaten woman with large breasts that flopped tiredly beneath a loose cotton blouse. Her hair, in contrast, was pulled up in a tight ponytail that accentuated the feline slant of her eyes.

‘You’re late,’ she said as she opened the door.

Claire and Bill Harrison lived in a large rambling house that was bereft of any particular style. Over the years they had added several extensions to the house and each new building project had little in keeping with what was there before. Now the house was an illogical sprawl of thatched roofs and glass skylights in between stranded patches of light and shade.

Mrs Harrison insisted on having her lessons on the patio which looked out onto the garden and the fields of corn that stretched away in the distance. The acoustics out on the patio were very poor but not so poor as to trouble a student with as little talent as she.

‘I’ll add on the extra minutes at the end,’ André said. He did not apologise and no apology was expected. He knew Mrs Harrison as a coarse, good-natured woman who forgot a rebuke as quickly as it was uttered.

André took his violin out of its case and busied himself with it for several minutes.

‘I don’t know why I bother,’ Mrs Harrison said with a sigh.

‘The thought has crossed my mind,’ André replied without turning to look at her.

He unfolded the music stand and clipped a photocopied page of sheet music to it. It was a beginner’s piece and not too difficult. It was marginally more advanced than Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, which they’d practised the week before.

‘Bill’s out all day today,’ Mrs Harrison said with good-natured irritation. ‘God knows where he goes.’ She cast a flabby arm in the direction of the fields. ‘It’s not as though the farm can’t take care of itself. I mean, the rain falls and the bloody crops grow. How much supervision does that need? But he’s off every day at the crack of dawn and doesn’t come back until nightfall.’

Her voice grated on André. Despite the years since she’d emigrated, Mrs Harrison’s accent was still more British than South African, more Manchester than Mthatha.

‘Farming’s difficult, Mrs Harrison,’ André murmured. ‘I should know. I grew up on a farm.’

They had this discussion before every lesson and André had learned to let his student ramble.

‘That’s right. In Bloem, wasn’t it?’

‘Yes.’

‘Terrible place Bloemfontein. Full of Dutchmen.’ Then she clapped a thick hand over her mouth. It was a game she played, a jolly attempt to provoke her music teacher. ‘I think I’ve put my foot in it again.’

‘That’s quite all right, Mrs Harrison. I don’t live in Bloemfontein anymore.’

‘It’s Claire. Only the bank manager calls me Mrs Harrison.’

‘Very well. Claire.’

‘You’ve never told me why you swapped Bloem for this godforsaken place.’ She jerked her head in the general direction of the city centre. ‘Don’t get me wrong, André, I’m glad I found you. I was going mad in stages with nothing to do. Nothing meaningful anyway.’

‘So that’s why you decided on violin lessons.’

Mrs Harrison nodded eagerly. ‘I simply had to learn something new. Bill doesn’t understand. He thinks I’m post-menopausal. Men can be such fools. I’ve been post-menopausal for years, not that he’d know the difference.’

André didn’t offer any comment and she carried on.

‘Other than yourself, André, I don’t think there’s a decent violinist within a radius of fifty miles.’

André replied with a ready smile. ‘And soon there’ll be two of us. Shall we begin?’

Mrs Harrison already had her violin out of its case. As usual, she struggled with the piece, fumbling over the notes from the very start.

‘Mrs Harrison?’ André said after a while.

‘Call me Claire. I won’t tell you again.’

He tried not to sigh. ‘Your posture. It’s all wrong. May I?’

He came around her and adjusted the angle of her arms, gently pushing her forearm and prodding her elbow until he was satisfied. It was slightly disconcerting to be in such close proximity to the woman. Her odour was warm and mildly unpleasant, with a piquant undertone of stale perspiration.

‘And please, Mrs Harrison,’André said. ‘No vibrato.’

She had taken to wobbling her fingers on the fingerboard of her violin whenever she played. It was an unfortunate habit she had picked up from television.

Mrs Harrison stuck out her lower lip. ‘None at all?’

André shook his head and motioned for her to play.

‘Oh, I’ll never be any good!’ Mrs Harrison exclaimed after a few minutes. She fell back into the padded cane sofa, which belched loudly under her weight. She looked despairingly at André.

‘Play for me?’ she said.

‘Of course.’

André began to play the first few bars of the nursery rhyme, only for Mrs Harrison to interrupt him.

‘I don’t mean that silly piece! Play me something proper.’

Dropping the bow to his side, but the violin remaining wedged against his neck, André looked at her. ‘Proper?’ he asked.

‘Yes! Something a real violinist would play. You know – Beethoven or Mozart. Or Brahms.’

André pointed the end of his bow at the music stand. ‘We really need to concentrate on your lessons,’ he said. ‘I’m not sure how my playing a more advanced piece of music will benefit you.’

‘You’ve never played anything proper for me,’ Mrs Harrison said with a pout. ‘If I didn’t know better, I’d say you couldn’t play the violin at all. At least not anything proper.’

A wave of heat sped up André’s neck and engulfed his face alarmingly.

‘That’s absurd!’

‘Then show me.’ Mrs Harrison drew her legs up on the sofa and settled back to wait.

‘All right,’ he said. ‘Here’s something proper for you.’

He played a few bars of Beethoven’s ‘Für Elise’. He found the piece repetitive, but he thought Mrs Harrison might recognise it. As he played he looked up at the ceiling fan above his head. It turned slowly, with languid revolutions that barely stirred the air.

‘Well?’

There was a look of rapt attention on Mrs Harrison’s face. ‘I don’t know,’ she said. ‘It doesn’t sound right without a piano, does it? Play something else.’

This time André let out the sigh he’d been incubating for so long. ‘We really should get back to our lessons, Mrs Harrison.’

Mrs Harrison folded her arms across her chest and glared at him. ‘I want you to play me something proper,’ she said firmly. ‘Or I’ll find myself another teacher.’

‘Very well.’

André didn’t think it wise to remind her that there were no other decent violinists within a radius of fifty miles. He’d learned that Mrs Harrison could be very determined when she wanted to and the look on her face was suddenly stern and forbidding.

‘Tchaikovsky,’ he said and it wasn’t a question.

Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto in D major was one of André’s favourite pieces, one that required all his concentration. The fingers of his left hand moved swiftly up and down the fingerboard and with the other he made the bow caress the strings with barely restrained ferocity. This was the only time he did not feel ungainly and uncoordinated – when he was playing the violin. One of his teachers had often said that his dexterity when he played was at odds with the clumsiness of his frame. André closed his eyes as his features contorted with pleasure. It was as if he were dreaming and playing in his sleep. With an impetuous slash of the bow, his upper body began to spasm with an almost sexual ardour … and that was when he saw them.

There were three of them. They swept in from over the cornfields, their wings beating powerfully like large birds, and came to a gentle stop at the edge of the patio. There they hovered, staring directly at André, without making a sound. It became noticeably cooler and the air tingled as though a storm were about to break.

André’s fingers stumbled momentarily but he dared not stop playing. These weren’t picture-book angels, all radiant in white robes and with pink, chubby cheeks made for blowing golden trumpets. No, the angels assembled in front of him were not like that at all.

The first angel was so pale his skin was almost translucent. Blood, because it could only be blood, coursed through a filigree of veins that ran up his calves and lost itself in the dark shadow between his legs. His chest was as broad and muscled as his arms and as he drew closer, his wings twitched powerfully, as if he might take flight at any moment. His wings were not a virginal shade of white as one might expect an angel’s wings to be. They were speckled with grey markings and heaved gently as the angel breathed, like two bunched, feathered creatures crouching on the angel’s back.

Then the second angel unfurled his wings with a sound like a heavy sheet snapped by the wind. André’s nose crinkled as a strong gust of air buffeted him. This angel’s wings were like a dragonfly’s but with none of the insect’s fragility. His wings split the sunlight into a million shards of iridescent colour that fell on the angel’s body in a brightly jewelled sheet. His penis was thick and hung in an imperious knot between his legs. He was perfection itself, a sculpture in mosaic into which some passing god had kissed life.

Suddenly André heard a voice growling in his ear.

‘So you think you’re a Christmas shepherd, my boy?’ His father – Trevor Barnes. ‘You see fucking angels, do you?’ Then the slither of leather on cloth as his father released his belt from his trousers and wrapped it around his fist.

André’s fingers stumbled again but now the third angel was above him. Unlike the other two, this angel’s forehead was criss-crossed with deep lines. His wings beat slowly and deliberately as though he were treading water. He had the look of a man who had seen too much and did not like much of what he saw. Then he tipped forward slowly from the waist, his feet lifting behind him as if there were a metal rod pinned through his hips. He turned unhurriedly through the air and stopped when his face was level with André’s.

They stared at each other for a long, drawn-out moment and André thought he saw a deep sadness in the angel’s eyes. Then the angel reached out his hand. To cup André’s chin or to draw him closer, André couldn’t tell. He shut his eyes. When he opened them again, the angels, all three of them, were gone.

Mrs Harrison rose to her feet and clapped with unrestrained enthusiasm. As she clapped, the folds of skin beneath her arms wobbled uncontrollably.

‘Bravo, André!’ she cried. ‘Bravo!’

‘Did you …’

‘Did I like it?’ Mrs Harrison exclaimed. ‘I loved it! You shouldn’t hide such talent, you know. I might only be a beginner but I must say, you’re bloody good.’

‘Thank you.’

André looked out across the fields where the heads of corn began their silent march to the horizon. The sudden chill had disappeared and he leaned against the wall to catch his breath.

‘Come and sit for a while,’ Mrs Harrison said in a kindly tone. ‘You look like you’ve run a marathon.’

André looked up at the clock on the wall. Like everything about Mrs Harrison, it was oversized and showed its age.

‘I’m afraid we’ve run out of time, Mrs Harrison. I really must be going.’

‘Won’t you have some water at least?’

‘No, thank you.’ He wanted to get away as soon as possible so he could be by himself. That was what he liked about Mthatha. Solitude was never far away.

‘You’re an odd little bugger, André Potgieter,’ Mrs Harrison said as she escorted him to the front door. She gripped his arm as if she might keep him with her a while longer. Her odour had changed. Now it was redolent of over-ripe fruit and freshly tilled earth.

‘Next Thursday then?’ she said.

‘I’ll let you know, Mrs Harrison,’ replied André.