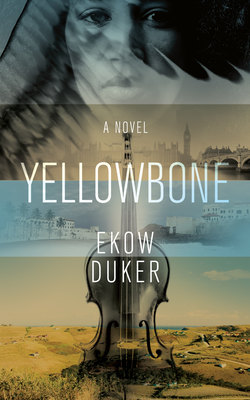

Читать книгу Yellowbone - Ekow Duker - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 8

ОглавлениеPrecious had come to believe that marriage was rather like an iceberg. For when a marriage falls apart, large chunks of it topple into an icy sea without making a sound. Nowadays when she and Teacher went to bed, they did so without speaking. Precious stayed cocooned on her side of the bed and her husband on his. It would have been the easiest thing in the world for her to roll over and hold him but somehow she couldn’t bring herself to do it. They both stared into the darkness and pretended to be asleep.

There seemed to be more and more things Teacher reproached Precious for. He rolled his eyes when she couldn’t do sums in her head. That hurt her terribly, especially when she remembered how patient he’d been all those years ago when she’d been in his class. She didn’t dress well enough for him anymore. He said the uniform she wore to church on Sundays made her look like an old matron. And on the rare occasions they went out together he walked a few steps ahead of her, as if he didn’t want anyone to know she was his wife. Teacher was falling out of love and Precious did not know how to catch him.

She was at her wit’s end when she decided to go and see Jabu, the diviner. She’d prayed to God about her marriage but sometimes Jesus could be slower to arrive than the municipal engineer. At least with igqirha, she put the money in his hand and for that reason she could hold him to account. What was more, Jabu’s house was only a short taxi ride away. He didn’t live in some indeterminate place with no address in a vast expanse of sky.

She dressed quickly and in her haste she almost stumbled over Karabo. Her daughter was sitting on the front step, tossing small stones at the empty space where Teacher usually parked his car. She looked up at her mother without much interest. ‘Where are you going?’ she asked.

Precious didn’t like Karabo’s forwardness. It was Teacher who had instilled that filthy habit in her. That was why she didn’t take Karabo to see uTata anymore. Since uMama had passed away, there was no reason to take Karabo anyway. uTata thought his grand-daughter was rude and why wouldn’t he, when Karabo had called him a drunken fool to his face? Precious had slapped Karabo hard for saying that. It was grief that led her father to drink but she didn’t expect Karabo to understand that. Perhaps Karabo called uTata names because she was mourning her grandmother as well. But if she was, that was a strange way to show it.

‘Oh, I just need to run an errand or two,’ Precious replied.

‘Can I come? I’ve nothing to do.’

‘Haven’t you any homework?’

‘I’ve done it.’

‘Surely you have a book to read?’

Karabo arched an eyebrow and looked at her mother as if to say, Really? The girl read almost as much as Teacher did. It often felt like a competition between the two of them, with Precious the odd one out.

Then Precious began to feel silly for casting about for reasons not to take Karabo with her. She was her daughter after all.

‘All right,’ she said with an exaggerated sigh. ‘You can come with me.’

Karabo sprang to her feet with an excited shriek. Standing, she was a head taller than her mother and Precious wondered for the thousandth time where her little girl had disappeared to.

‘But you must wear something decent,’ she said, looking disapprovingly at Karabo’s shorts and T-shirt. The T-shirt stopped well above the child’s belly button and her shorts started an equal distance below. ‘People will think we can’t afford to buy you clothes.’

Karabo bounded into the house and came back in the dress Ma’ama had sent her from Ghana. It was made of cotton with black and yellow markings, which Teacher said were symbols of prosperity and long life. Karabo had been overjoyed when the dress arrived in the post. It wasn’t so much the fact that Ma’ama had sent it that made Karabo so happy; she was just thrilled to have something from the place her father came from.

The neckline of the dress scooped low to expose the swell of Karabo’s breasts. Precious was about to send her back inside to put on a bra, but she didn’t want Karabo to think of her as the prudish old matron Teacher had said she’d become, so she let it go. She followed her daughter through the gate.

‘You don’t have to pay,’ the driver said to Precious as they boarded the taxi. It was not unusual. This happened to Precious rather often, when a black man in awe of her complexion would offer her a random favour. And with the even lighter-skinned Karabo by her side, the effect was only magnified.

‘But I must pay,’ insisted Precious. Had she been alone she would gladly have accepted the driver’s offer but she didn’t want to teach her daughter the wrong lesson. However, Karabo barely looked at the driver and quickly took her seat. It was as if she was already used to such acts of colour-induced largesse.

Karabo kept asking where they were going until Precious had to pinch her to be quiet. She was too embarrassed to say they were going to see igqirha. His house was in a much less respectable part of Mthatha than where they lived. There all the fascia boards were askew and the paint was falling off the houses in leprous, greying scabs. A pavement special kept pace with Precious and Karabo for a while after they got out of the taxi to walk the short distance to Jabu’s house. The dog trotted alongside them like a guard of honour.

Precious raised her hand and shouted at it. ‘Get away!’ It froze and stared at her with one paw raised off the ground. ‘Get away!’ she cried again, but it slunk away only when she bent down and pretended to pick up a stone to throw at it.

A group of boys ahead of them heard Precious shout and they turned to see who it could be. They were teenagers, about Karabo’s age, all dressed in drab cotton trousers and faded shirts. Precious held Karabo’s hand tightly and as they hurried past, one of the boys called out in a loud voice, ‘Yellowbone!’ The boys laughed loudly and made obscene sucking noises. Precious felt Karabo stiffen and slow down. She had to tug on her hand to keep her walking.

‘Look, we’re here,’ Precious said with a happy cry. She wasn’t really feeling happy but she thought she should put on a show for Karabo.

But Karabo kept looking back at the boys and Precious had to bundle her into Jabu’s yard. She cursed Teacher under her breath for telling Karabo to always stand up for herself. That sort of chat-show life lesson could get you killed in Mthatha.

‘Wait for me here,’ she said to Karabo, pointing to the next room. She would have sat with her for a few minutes but it wouldn’t do to keep igqirha waiting.

She patted Karabo on the shoulder to reassure her but she didn’t seem to notice. She looked pensive, like she was working out one of Teacher’s bloody sums in her head.

Precious knocked on the door and when she entered she found Jabu Molefe seated cross-legged on the bare floor. He was still in his blue overalls, the ones with yellow reflective stripes around the elbows and ankles. He looked more like the municipal labourer he was than a man who wrestled daily with spirits and imparted wisdom to allcomers. There was a straw mat spread out in front of him and on it were neat bunches of herbs tied with blades of dried grass, an assortment of coloured beads and an enamel cup half full of water.

Precious felt a little cheated that Jabu hadn’t bothered to change out of his overalls. The last time she’d seen him he’d been wearing a grass skirt with leather amulets tied around his biceps. At least he could have messed up his hair a little.

‘You have come.’

His voice was deep and resonant, just how igqirha’s voice should be.

Precious smiled. Perhaps she’d get her money’s worth after all.

‘What brings you here, my daughter?’

She wished Jabu wouldn’t call her that. He’d been two classes behind her at school. She shut her eyes and tried to focus on the fact that he was igqirha now, at least when he wasn’t cutting grass for the municipality.

‘You know why I am here. It is my husband.’

She thought his eyes glimmered but it was difficult to tell in the half light.

‘The teacher?’

‘Yes – Teacher. My husband.’

Jabu bent his head and stirred the beads with a dry twig. Then he dipped his hand into the cup of water and, without warning, flicked his fingers at Precious. She recoiled and cried out in alarm, feeling strangely humiliated, as if he had spat at her. But she did not dare wipe her face.

‘Does he know you?’

‘What do you mean, Jabu? He is my husband. Of course he knows me.’

Jabu slipped his hand between his legs and cupped his crotch.

‘My daughter, I asked whether your teacher knows you.’

Precious’s face burned with shame at the turn Jabu’s questions had taken.

‘No, Jabu,’ she said quietly. ‘Not for several months.’

He bent his head again and rummaged among the items on the mat. His hands were dry and covered in small scars. He muttered a few words to himself, then handed Precious a brown kidney-shaped nut.

‘Eat,’ he said.

Precious reached across and took the nut from him, taking care not to let her hand touch his. When she bit into it a peppery taste flooded her mouth. Jabu watched her carefully until she had swallowed the last piece.

‘I see the cause of your troubles, my daughter.’

‘Tell me,’ she said eagerly.

‘It is a woman.’

What woman? Did Teacher have a girlfriend? Precious ran through the women she’d seen around Teacher, scoring them against their likelihood of mischief. She didn’t trust Dorothy Mpetla. The bitch read the notices in church and spoke isiXhosa like an Englishwoman, clicking her tongue in all the wrong places. But it was common knowledge that Dorothy only had eyes for the Nigerian pastor, so Precious struck her off the list. But what about Eunice Matabela, the new school principal? Teacher spoke of her often and with admiration. Eunice was married, not that it mattered these days. If not Eunice or Dorothy, could it be that Venda girl in Grade Twelve, the one whose parents paid Teacher to give her extra maths lessons after school? She was tall and sullen with a body that spoke more than she did, the sort of body a man liked. Precious was still trying to remember her name when Jabu’s voice rolled through the gloom.

‘She is here.’

Confused, Precious glanced quickly behind her. ‘You mean Karabo? But she’s not a woman, she is my daughter.’

‘I have answered your question,’ Jabu said firmly. A fly whisk appeared in his hand and he began to beat himself gently about the shoulders with it.

Precious thought the firmness of his tone was ironic for Jabu had never been able to answer any questions at school.

‘No, you are mistaken. Karabo is not to blame,’ Precious said anxiously. ‘She is only a child.’

‘There are no children in this house,’ Jabu said and a chill ran down Precious’s back. Then he dipped his hand in the cup and flicked his fingers at her again. The water tasted like it had been drawn from a dark and ancient well and this time Precious wiped her face with the back of her hand.

She had been hoping Jabu would tell her something else. That it was indeed Dorothy Mpetla or Eunice Matabela who was the cause of her troubles. Or the Venda girl with the long slim legs whose name she couldn’t remember. She’d rather it was one of them instead of Karabo. It would have been much easier that way. She felt angry and bewildered and ashamed, all at the same time. She couldn’t bear to think of what Jabu had just said, for how does a mother denounce her own daughter?

Then Jabu lit a small candle and she was grateful for that because the room had grown so dark she could hardly see him. But when had he unzipped his overalls? His bare chest glimmered in the candlelight. His breasts were a size larger than hers and his belly sloped forward, coming to rest in a contented heap between his legs. At school Precious used to tease Jabu about his weight. She hoped he didn’t remember.

Suddenly, he tossed a broken piece of mirror across the mat towards her. It lay there, glinting wickedly, like a sliver of a star that had somehow fallen from the sky. Precious looked down at it, not knowing if she should pick it up or leave it where it fell.

‘She will go back to her people,’ Jabu said.

‘Which people?’ she cried. ‘Go back where, Jabu?’

He grunted and pointed his fly whisk above his head. Precious looked up but all she could see were the shadowy traces of wooden beams.

She didn’t understand. ‘Must my daughter climb up on your roof?’ she asked.

Jabu began to beat himself about the shoulders with the fly whisk again. He didn’t say anything else. It looked like he was done. That was the problem with amagqirha, Precious decided. You never knew what you would get. She sighed and tucked a fifty-rand note under the corner of the mat. As she got to her feet, Jabu flicked his fly whisk at her. She was dismissed.

Precious hurried to the room where she’d left Karabo. For some reason, she knocked on the door before she went in.

‘Karabo?’ She pressed her cheek against the door. ‘I’m finished.’

When there was no reply Precious thought her daughter might have fallen asleep. She pushed the door open and saw only an empty chair.

Karabo wasn’t there.