Читать книгу Stella - Emeric Bergeaud - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Stella in Context

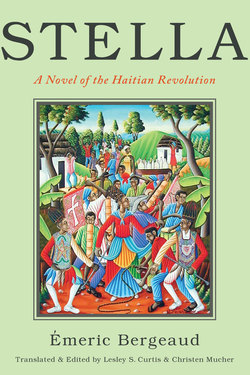

ОглавлениеWhile Stella has the honor of being Haiti’s first novel, Haitians were active producers of literature—including long works of fiction—before 1859. Hérard Dumesle’s Voyage dans le nord d’Hayti, ou Révélations des lieux et des monuments historiques (1824), for example, recounts a story of travel that is, at least somewhat, fictionalized. La Mulâtre comme il y a beaucoup de blanches (1803), an epistolary novel written by an anonymous woman from Saint-Domingue, could also merit the title of Haiti’s first novel, although it was published before independence.41 Stella emerged from a rich literary context in which public discussions of politics and history, and the relationship between story and history, were inextricable.42

The unusual mixture of history, politics, and literature that defines the writings of early Haitians also stems from the fact that many authors were both politicians and writers. Félix Boisrond-Tonnerre (1776–1806), for example, who attended school in France and was Dessalines’s personal secretary, both drafted the Declaration and penned his own history of the Revolution, Mémoires pour server à l’histoire d’Haïti.43 Pompée Valentin de Vastey (1781–1820), apologist for and secretary to King Henri Christophe, wrote to audiences in France and Britain decrying the colonial system and demanding that Europeans recognize the humanity of African and African-descended people. Others, including Juste Chanlatte (1766–1828), Jules-Solime Milscent (1778–1842), and Jean-Baptiste Romane (1807–1858), circulated their writings in the era’s literary and news magazines, such as L’Abeille Haytienne, L’Eclaireur haïtien, and L’Union. These periodicals reported political events alongside poems and short stories that also often had political aims. Dumesle, whose 1824 travel narrative recounts a story of the Bwa Kayiman ceremony in French and Kreyòl, was also a politician and leader of the movement to oust Boyer in the 1840s.44

Though influenced by the same tradition of intertwining history and politics, Bergeaud belongs to a slightly later generation of authors known as the “School of 1836.” Other journalists, poets, and historians of the school include Émile and Ignace Nau (1812–1860; 1808–1845), Beaubrun, Céligny, and Coriolan Ardouin (1812–1836), and Beauvais Lespinasse (1811–1863).45 Debates over language and nationalism shaped the writings of the School of 1836, as it had those of their predecessors. Members of the group aimed to follow its motto—“Be ourselves”—and to cast off previous literary and linguistic models in a search for Haitian styles. For example, the movement’s founder, Émile Nau, advised his followers to “naturalize” their adopted language by lending it Caribbean cadences and a “warmth” it never had in France.46 Ardouin argued similarly for the importance of his French’s Caribbean difference.47 Stella’s inclusion of a creole story and proverb attest to a similar approach by Bergeaud.

Much of the search for a Haitian identity in literature, history, as well as politics was marked by the challenges the country faced in its first half century. In 1814, Vastey predicted that the printing press would be a tool for exposing the crimes of colonists and for responding to the false accusations of prejudiced historians of the Haitian Revolution.48 Members of the School of 1836 continued to use the written word as a means to defend Haiti and its independence. To refute calumnies made against their country—usually claims that Haiti’s continuing problems were due to the circumstances of its founding—many early Haitian authors wrote histories. Bergeaud’s Stella follows Dumesle’s Voyage and Thomas Madiou’s (1814–1884) Histoire d’Haïti (1847) in this vein; moreover, Ardouin, the historian who published the novel, certainly contributed to its blurring of the lines between history and fiction.

Stella’s distinctiveness comes from the fact that it is a fictionalized account of the Haitian Revolution that places Haiti’s history in an explicitly positive context. This perspective ran contrary to that of much literature on similar topics produced at the time. Not only is Stella one of the few positive representations of the Haitian Revolution written in the nineteenth century, it is, along with Pierre Faubert’s play, Ogé, ou le préjugé de couleur (1856), one of the first fictionalizations of the Haitian Revolution to be written by a Haitian. Other early fictional accounts of the Revolution—such as Jean-Baptiste Berthier’s Félix et Éléonore, ou les colons malheureux (1801), Réné Périn’s L’Incendie du Cap, ou le règne de Toussaint-Louverture (1802), Leonora Sansay/Mary Hassal’s Secret History; or, the Horrors of St. Domingo (1808), Mlle de Palaiseau’s L’Histoire de Mesdemoiselles de Saint-Janvier, les deux seules blanches conservées à Saint-Domingue (1812), E. V. Laisné de Tours’s L’Insurrection du Cap ou la perfidie d’un noir (1822), Victor Hugo’s Bug-Jargal (1826), and Fanny Reybaud’s Sydonie (1846)—all present Haiti’s history from the viewpoint of Europeans. Bergeaud was, no doubt, familiar with some, if not all, of this literature. Indeed, the first section of Stella reads much like the sentimentalist antislavery literature that was part of a slowly reemerging French abolitionist movement beginning in the 1820s.49

Stella thus might have seemed somewhat familiar to French readers at the time of its publication in Paris, despite its pro-Haitian message; Bergeaud sought to capitalize on this familiarity in order to reach a population that did not, he admits, often concern itself with an “in-depth study of our annals.” The novel’s publication, during a time when other Haitians were writing and publishing in Paris, however, also encouraged a new French approach to remembering its former colony. Fighting back against a French tendency to denigrate Haiti was a project with admittedly limited impact. The end of slavery in its overseas colonies in 1848 in fact allowed France to return to the troubled subject of Haiti in a way that ignored the reasons for the country’s 1804 loss of its prized colony, contributing to a general amnesia surrounding the Saint-Domingue expedition’s goal to reestablish slavery. Typically, when the French read or wrote about Haiti, their nostalgia for the former colony of Saint-Domingue mixed with anxieties about what Haiti meant for France’s international standing; this combination made Haiti into a literary subject consistent with nineteenth-century themes of melancholy and loss.50 The French often approached the topic with questions about what went wrong or what might have been.

The second abolition of 1848, however, meant that metropolitan French and outre-mer readers alike were able to celebrate a newly authorized diversity permitted by the end of slavery. In the years following, Paris saw a wave of works about Haiti written by Haitians. These include Beaubrun Ardouin’s Études sur l’histoire d’Haïti (1853–1865); Céligny Ardouin’s posthumously published Essais sur l’histoire d’Haïti (1865); Pierre Faubert’s aforementioned Ogé, ou le préjugé de couleur (1856); and Joseph Saint-Rémy’s Vie de Toussaint Louverture (1850), Mémoires du Général Toussaint-L’Ouverture écrits par lui-même (1853), and Pétion et Haïti (1853–1857). In contrast to the literature written by their French counterparts—who often understood colonialism and slavery as separate institutions—the works of these authors sought to defend Haiti’s sovereignty by explaining that independence had been the only way to guarantee Haitians’ freedom from slavery. At a time when the abolition of 1848 overshadowed memories of slavery’s 1794 abolition and its 1802 reestablishment, this insistence on the necessity of independence often went unheard. Nevertheless, Stella takes a similar approach.

This attempt to appeal to a French audience, along with Bergeaud’s French heritage and erudition, have contributed to modern-day criticism of Stella.51 Bergeaud fits the profile of an elite Haitian “francophile” of the mid-nineteenth century: someone who spoke French, practiced Catholicism, and followed French literary and artistic fashions. In his novel, Bergeaud is clear about his appreciation for France’s language, religion, and culture. More than one critic has noticed that, although he was presumably writing for a Haitian audience, Bergeaud consistently employs European and classical imagery, such as figs, the Alps, and Apollo.52 The few instances of native plants or materials—ironwood or makoute, for example—that do appear in Stella are usually explained for the reader. Yet the very fact that he wrote Stella with an eye toward France helps us to place Bergeaud, as well as his novel and his history, in the context of his social class and political milieu. His literary choices hint at the contemporary life of a particular class of Haitians in the nineteenth century, and they highlight the importance attached to their presentation of national history. It is via his particular expression of “francophilia” that Bergeaud is able to suggest that the ideals of republican equality were truly realized in Haiti, not France, and thereby argue for Haiti’s right to be recognized among the world’s nations.

Nevertheless, Bergeaud does combine Haitian and French literary traditions in his writing, perhaps in response to Émile Nau’s call for new literary forms. In 1837, Nau suggested that young Haitian writers should study all schools of literary thought but “belong to none.”53 Stella responds to this call through its own attempt to blend history and literature, but Bergeaud’s novel is also very clearly written in the style of the historical romance, that is to say, the form made famous by Sir Walter Scott, Victor Hugo, and James Fenimore Cooper. Like the historical texts written by these giants of the nineteenth-century Atlantic literary world, Stella takes the general outline of a historical event and recasts its details through the lives of invented, even abstracted characters, not unlike Edward Waverley, Jean Valjean, or Natty Bumppo. As in the genre popularized by Scott, much of the action in Stella, especially the military accounts, is taken from published historical sources. Indeed, much of the novel’s historical detail comes from Ardouin’s Études sur l’histoire d’Haïti, possibly inserted by the editor himself; but Bergeaud also draws on information from Pamphile de Lacroix’s La Révolution d’Haïti (1819), Antoine Métral’s Histoire de l’Expédition des Français à Saint-Domingue sous le consulat de Napoléon Bonaparte (1825), and Madiou’s Histoire d’Haïti. However, unlike historical work at the time, Stella unites the threads of different historians—particularly Madiou and Ardouin—by portraying the Revolution as both a successful slave uprising and a national independence movement.54 Furthermore, Bergeaud weaves aspects of allegory—both in terms of rhetorical device as well as generic form—together with abstraction and symbolism so that the novel is not explicitly controlled by any one device or formal approach. While Bergeaud builds upon previous models, ultimately Stella takes a form of its own.

Bergeaud’s narrator explains that the presentation of a fictional, rather than a historical, account allows for an exploration of the hidden human motives behind the struggle for freedom:

History is a river of truth that follows its majestic course through the ages. The Novel is a lake of lies, the expanse of which is concealed underwater; calm and pure on the surface, it sometimes hides the secret of the destiny of peoples and societies in its depths . . .

For Bergeaud, history’s sight is “limited to the horizon of natural things,” and thus cannot always know that which is beyond the horizon: “History leaves the field of mystery to the Novel. [. . .] The Novel tells the secret story.” It was Bergeaud’s design to develop interest in the history of Haitian independence through the popularity of the genre of the novel, and it therefore makes sense that he would choose as his model a literary form that overtly combines both fiction and history. For although Bergeaud insists that Stella is more of a novel than a history, the exact genre to which it belongs might be said to exist somewhere in between. In fact, its distinctiveness has led to confusion as to how to classify Stella, which has also led to difficulties in judging its literary value; these problems have contributed, in part, to the novel’s obscurity up to this point.55 In particular, Stella’s deviation from Scott’s genre involves Bergeaud’s connection to epic and oral storytelling traditions, evidenced through the author’s consistent use of “we,” and illustrated in, for example, the family scene in the ajoupa. If one of the aims of the School of 1836 was to distill familiar, oral renditions of history into a new written genre, Stella follows those indications well. In this way, his novel has more in common with Nau’s “contes historiques” or “contes créoles” and Dumesle’s travel writing than with Scott’s romances.56 Bergeaud’s goal of reaching both French and Haitian readers mirrors his novel’s combination of Haitian and European literary traditions.