Читать книгу Stella - Emeric Bergeaud - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Editors’ Introduction

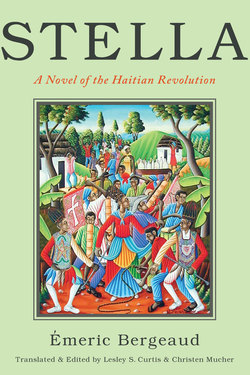

ОглавлениеÉmeric Bergeaud (1818–1858), Haitian politician and man of letters, explained in the prefatory note to Stella that he had taken pains not to “disfigure history” in the writing of his only novel. Although Stella’s main characters—Romulus, Remus, the Colonist, Marie the African, and Stella—are fictional, Bergeaud assured his readers that there was truth in the book he wrote to honor his country. He wanted the “attraction of the novel” to “capture” readers “who do not subject themselves to in-depth study of our annals.” Like other Haitian writers of the nineteenth century, Bergeaud believed it was crucial to retell the Haitian Revolution from a positive perspective so as to counter the hostile representations of his country that were so common at the time. For this reason, the novelist wanted his story of Haiti’s transformation from French colony to independent nation to alter the perception of his native country both at home and afar.

Stella, the nation’s first novel, seeks to enshrine the Haitian Revolution and the Haitian people as the true inheritors of liberty, and Haiti as the realization of the French Revolution’s republican ideals of freedom, equality, and brotherhood. Stella tells of the devastation of colonialism and slavery in the colony of Saint-Domingue, as Haiti was known before independence, and it chronicles the events of the Haitian Revolution, which is portrayed as a bloody yet just fight for emancipation and a period of sacrifice that all future Haitians are charged to honor and remember. While Stella provides a captivating and admirable origin story for Haiti and Haitians, the fact that it was out of print for more than one hundred years means that the novel has struggled to fulfill its author’s wish of attracting a wider readership to his nation’s history.

When Bergeaud wrote Stella in the late 1840s and into the 1850s, he was living in exile on the small Caribbean island of Saint Thomas (now part of the U.S. Virgin Islands). When the novel was finally published in 1859, it appeared in Édouard Dentu’s busy Parisian bookshop rather than on the bookshelves of Charlotte Amalie or Port-au-Prince.1 Bergeaud had given the manuscript to his friend and relative, the historian and politician Beaubrun Ardouin (1796–1865), also in exile, when the two were together in Paris in 1857. After Bergeaud’s death the next year, Ardouin had his friend’s novel published in the City of Lights. It was never printed in Haiti. That Stella appeared in Haiti’s former colonial capital was due as much to Bergeaud’s personal circumstances and Haitian politics as it was to the cachet of the nineteenth-century Parisian literary scene.

The legacy of the novel’s publication history, Bergeaud’s particular blending of history and fiction, as well as an unfortunate general hostility toward early Haitian literature continue to influence how Stella has been received over the last century and a half. Despite Stella’s strong message against slavery, colonialism, and the racism intrinsic to these systems, the novel has been understudied. The few studies of Stella that exist—and in this sense, Bergeaud’s novel is representative of a wider trend in the reception of early Haitian literature—have tended to view the novel as derivative of French literary models and therefore imperfect or unworthy of study. The bases for these dismissals, and the novel itself, deserve to be reexamined.2

The goal of this introduction is to contextualize Stella’s political and literary world for an English-speaking audience. Here, we provide a brief overview of the history that Stella relates, for while the novel certainly provides insight into the political and social conflicts of Bergeaud’s world, a reader unfamiliar with the intricate details of Haitian history may find following the novel’s allegorical account of the nation’s founding challenging.3 In making Stella and the story of Haitian history that it recounts available to Anglophone readers and thereby introducing the novel to a new generation of scholars, it is our hope that Haiti’s first novel will find its place within a revitalized study of early Haitian literature.