Читать книгу Stella - Emeric Bergeaud - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

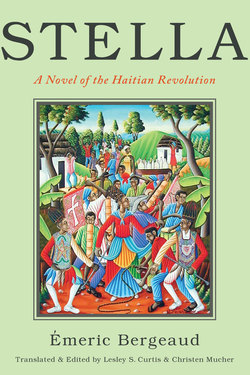

Reading Stella

ОглавлениеAt the time of Stella’s publication, the population of Haiti was categorized and hierarchized according to color and class based on divisions inherited from the colonial era. After independence, some categorizations changed shape and the country further split along the lines of region, religion, and language. Haiti’s population differed most considerably from that of Saint-Domingue in that much of the white population had either fled the island or perished during the final days of the Revolution, a moment described in Stella with regret. In the early years of the country, the peasant or cultivateur class also expanded, which resulted in the development of a social distinction based on whether one lived in one of the wealthy cities (gens de la ville) or the rural outskirts (moun an deyò).57 Although skin color continued to be a defining characteristic in nineteenth-century Haiti, some political distinctions that seemed to be based on color—such as the constant conflicts between what have been called the “mulatto” or Boyerist and the “noiriste” or black populist factions—were often the result of intersecting differences in heritage, class, region, religion, and language; assumptions that a given person acted solely on the basis of skin color are frequently inaccurate.58 While the racialist distinctions that shaped the political world in which Bergeaud wrote had their bases in the colonial era, when they were specifically tied to issues of wealth, culture, language, and degrees of freedom, the social divisions of the early national period were not simply based on race or color prejudice. Stella both illustrates and responds to early Haiti’s cultural divides, and locates the origins of the history of difference and disunion in the machinations of the greedy Colonist.

Bergeaud’s insistence on the connection between his main characters, the fraternal founders of Haiti, has much to do with his decision to name them after the mythical twin founders of Rome. As does the figure of the Colonist, the brothers represent, however, multiple historical characters. They embody the actions and spirit of most of the revolutionary leaders: Romulus represents, at times, Toussaint Louverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and Henri Christophe, while Remus is André Rigaud, Alexandre Pétion, and Charles Boyer. The brothers are the allegorical representations of the division—and eventual reunion—of the two dominant classes of Haitians at the time: the formerly enslaved black population and the Euro-African population. Bergeaud avoids discussing the division between those freed before 1793 and those freed after by making the experience of slavery common to both brothers who also share the same connection to Marie l’Africaine, Mother Africa. The other characters in the novel—Stella, Marie the African, and the Spirit of the Nation—are allegorical representations that portray archetypes rather than specific people from Haiti’s past. Stella is structured by its dedication to history, and its allegorical elements emphasize that Haiti’s transformation is significant not just to Haitians but to all humanity.