Читать книгу The Common Lot and Other Stories - Emma Bell Miles - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеintroduction

The Published Short Stories of Emma Bell Miles, 1908–21

GRACE TONEY EDWARDS

They are all romance, these luxuries of the mountaineer,—music, whiskey, firelight, religion, and fighting: they are efforts to reach a finer, larger life,—part of the blue dream of the wild land. Who knows him? . . . Who has tracked him to that wild, remote spot, echo-haunted, beautiful, terrible, wherein he dwells? (Emma Bell Miles, Journal, I, November 13, 1908)1

So asked Emma Bell Miles as she reflected on the mountaineer’s love of a roaring fire to warm his cabin when winter’s storms pushed him indoors. In her fiction she took up the trail leading to that “wild, remote spot . . . wherein he dwells.” She explored his romantic luxuries: the music, strong drink, fighting, home fires, and religion. But the references to “him” and “his” are not neutered pronouns; the romantic luxuries are clearly those of the mountain male. As she says in her fictionalized ethnography, The Spirit of the Mountains, “He is part of the young nation.” The woman, on the other hand, “belongs to the race, to the old people.” “Her lot is inevitably one of service and of suffering, and refines only as it is meekly and sweetly borne.”2

Miles spoke from years of observation and participation in the lifestyle of the people she grew up with and chose to live among on Walden’s Ridge, one of the bare-rock bluffs that rise above the city of Chattanooga, Tennessee. Emma Bell was not born in those Tennessee highlands but moved there with her schoolteacher parents from Rabbit Hash, Kentucky, when she was eleven years old. An only child of Ben and Martha Mirick Bell, she was primarily home-schooled on the classics of great American literature and, as she put it, a steady diet of Harper’s Monthly Magazines. She loved the outdoors and was given free rein to roam the woods and learn the flora and fauna of her environment firsthand. In her teen years, she developed an interest in art, and eventually, through the efforts and influence of Chattanooga art patrons, she enrolled in the St. Louis School of Design, where she studied for two terms. Amid talk of sending her to Paris for further study, she made a decision to return to her “blue mountains” and a young mountain man who had won her heart. In October 1901 Emma Bell married Frank Miles.

And so began her life as a mountain wife and mother. In September 1902 she gave birth to twins Judith and Jean. During the next seven years she bore three other children, Joe, Katherine (Kitty), and Mirick (Mark). She also began to write seriously and succeeded in placing several poems and several short stories in popular magazines. In 1905 James Pott & Company published her book The Spirit of the Mountains. From time to time she traveled down to Chattanooga to paint portraits, landscapes, and murals on art lovers’ walls. Though her life appeared to be very full, it was also very hard. She and Frank struggled to provide food and shelter for their brood; they made numerous lateral moves from one rental house to another; and Emma’s earnings, paltry as they were, often had to carry them through.

By the start of her second decade of marriage, Emma’s health had begun to fail. Somewhat frail even as a child, she suffered in adulthood from years of frequent childbearing and miscarriages, hard work, and inadequate housing and food. She also suffered the emotionally debilitating loss of her youngest child, Mark, who died of complications of scarlet fever shortly before his fourth birthday. Blaming their desperate poverty and striving to provide better for her other children, Emma landed a job at the Chattanooga News in 1914 and for several months wrote a column called “Fountain Square Conversations.” She lived in the Frances Willard Home for Working Girls and for a time enjoyed a bit of freedom from the daily toil of housekeeping and motherhood. That respite was not to last, “sacrificed,” as she put it, “to a man’s pleasure” (Journal, July 24, 1914).3 Pregnant again and ill, she had to resign from the News, only to lose the baby a few weeks later. Ultimately she was diagnosed with tuberculosis and confined for periods of varying duration in Pine Breeze Sanitarium in Chattanooga. Ill health and wracking poverty notwithstanding, Emma Bell Miles managed to publish or sell during her lifetime more than one hundred poems, including those in a self-published booklet called Chords from a Dulcimore; seventeen short stories; a series of newspaper columns; and two books. The second book, entitled Our Southern Birds, was completed during her last stay at Pine Breeze and was launched just two weeks before her death on March 19, 1919. She was thirty-nine years old.4

The seventeen short stories in this collection constitute all of Miles’s known fictional output. There were most likely other stories drafted, as indicated by her journal entries and letters. In his introduction to Once I Too Had Wings:The Journals of Emma Bell Miles, 1908–1918, Steven Cox lists titles of works that Miles says she has written and in some cases submitted for publication, but these have not come to light. However, I suspect that at least two of those in Cox’s list may have been published under titles other than the ones given in her journals and are in fact present in this collection.5 All of the major magazines of her era, such as Harper’s, Lippincott’s, Putnam’s, Century, Craftsman, and Red Book, have been thoroughly searched, as have the smaller, more obscure publications that she wrote for, including Mother’s Magazine, Youth’s Companion, Nautilus, and The Lookout. These seventeen stories are the result of those searches.

Some scholars have theorized that she may have allowed other writers to publish her work under their own names. Possibly that happened, for we know from her journals and letters that she collaborated extensively with Caroline Wood Morrison in 1908; she also wrote that she worked closely in 1908–10 with the sisters Alice McGowan and Grace McGowan Cooke, drawing illustrations and providing ideas for their books. All three of these collaborators, writers of some renown in Chattanooga, were publishing novels and stories set in Miles’s own home territory during the period from 1908 to 1910. A study of their work shows that they clearly benefited from Miles’s knowledge of the mountain people and her wordsmithing talents; what she gained from them is less clear. However, she may have allowed them to borrow her ideas, her drawings, and even her actual writing because they were better established than she and perhaps promised help in getting her work published.

Whatever the case, in the seventeen stories that we know were written by Emma Bell Miles (including one in collaboration with Caroline Wood Morrison), as well as in many of her poems and essays, her perceptions of men’s and women’s opposite realms of existence infuse the corpus of her work. Feminist that she is, her writings belong generally to the local color school, though literary historians usually claim that the local color movement was in decline by the time Miles began to publish.6 In the decade following her death, a new regionalism reached fruition, its proponents sharing a strong sense of place with the local colorists but imbuing their fiction even more overtly than most of their predecessors with social motives. According to critics Harry Warfel and Harrison Orians, “Authors wrote to support theses rather than to photograph a group of people against a setting.”7 Emma Bell Miles’s fiction and nonfiction stand between these two closely related impulses, her form and style taking their pattern largely from the nineteenth-century local colorists—that is, “photograph[ing] a group of people against a setting”; her purpose, however, with its intense seriousness, providing a bridge to the twentieth-century regionalists.

Miles’s stories can be profitably examined by these standards, for her whole body of fiction is a crusade for the liberation of women, coupled in her mind with the oppression of poverty. Yet Miles was well aware that poverty alone does not fetter women; in her Appalachian Mountain culture, as in most others throughout America, the traditions of the patriarchal society determined woman’s place.

Miles approached her subject matter at a time when the organized suffrage movement was still relatively new in the South, and virtually unknown in the mountain South. In her stories her vision of women and their utter dependence on marriage localizes itself to the Southern mountains, in reality her own Walden’s Ridge, Tennessee. Others were also writing about the Appalachian Mountains during this same period. “Somewhere on [her] blue horizon”8 reigned the queen of mountain fiction, Mary Murfree, whose view of the mountaineer fixed itself in the minds of Americans and to some extent remains there today. John Fox replicated Murfree’s picture to become one of the most popular authors in the country soon after the turn of the century. Dozens of other writers flocked to the Appalachians to view the scenery, to poke and prod the natives—if they dared—in their research for their next “piece.” Constance Fenimore Woolson put in her time on the Blue Ridge near Asheville; Joel Chandler Harris paid some visits to folks he knew up in North Georgia; Lucy Furman set up shop at Hindman Settlement School in Knott County, Kentucky. But Emma Bell Miles did not have to go anywhere: she looked out her door; she listened to Frank, to Grandma Miles, to sister-in-law Laura Hatfield, to Aunt Lucy, to her babies. She wrote about the Appalachian mountaineer from home, and the view looked different from there. In 1914, after she had already composed most of her fiction that came to print, she remarked to an unidentified correspondent, “To one who has lived the life, the ordinary novel of moonshine & rifles seems merely newspaper twaddle.”9

It is hardly a wonder that Miles should ignore, if not reject, the “otherness” of Appalachia that critic Henry Shapiro claims was not initiated by, but solidly established in, Murfree’s fiction.10 The perception of otherness actuated an opposition between Appalachia and the rest of America, a strange incongruity, for the mountain region had once been the frontier of America. Its settlers, both those who stayed and those who passed through, were America’s settlers. But somewhere along the way, partially because of the region’s insularity, the ordinary changes of civilization were arrested. Appalachia retained into the twentieth century folkways attributed to ages and places as diverse as Chaucer’s England and eighteenth-century America. In the fervid search for local color by those who lived beyond the mountains, the differences, the otherness, spotted among the mountaineers became a rich vein to be mined. In fiction the contrast, and ultimately the opposition, between the familiar and the unfamiliar has been emblemized by the conflict between insider and outsider, represented most often by moonshiners and revenuers, feudists and lawmen, mountain girls and city boys.

But little of that touched Emma Bell Miles. She “lived the life”; she did not need to create dramatic tension through conflict between insider and outsider. She saw it daily between insider and insider, between woman’s dream and her reality. She verbalized her own concept of the normalcy of Appalachian culture when she wrote in 1907 to Anna Ricketson, a friend by correspondence in New Bedford, Massachusetts: “It is often hard for me to notice points of difference between our way of life and civilization, I am so used to the backwoods.”11 Her fiction does not build from without, then, as does that of other writers about Appalachia in her time. It grows from within, showing respect for the traditional folkways that have sustained the mountain people, but at the same time crying out against the cultural bonds that restrict, limit, and dehumanize the women. Her characters are mountaineers, but they are not peculiar or different from common people anywhere.

Three years elapsed between the publication of Miles’s fictionalized ethnography, The Spirit of the Mountains, and the first of what I am calling her “quasi-fictional” stories, a term not meant to diminish her work but rather to explain it as a type of discourse that draws from both literary and expository writing with a definite aim to convince and persuade. In a bit of prepublication criticism, she showed that she knew the qualities of her own writing, qualities that she seemed to consider detriments to her success. To Anna Ricketson she wrote in 1907 of her stories: “Mine generally lack the keen interest of action and plot which ‘The Circle’ [prize competition] makes a first consideration.” A few days later she continued, “I think my stories will never be popular; they are too serious. . . . Perhaps I shall acquire a lighter touch as the children grow older and the daily stress is somewhat relieved.”12

Two striking points emerge from this self-assessment. First, Miles is aware that her writing does something different from standard fiction; it lacks the “keen interest of action and plot.” At this stage in her life she could not recognize that the chronological mode of fiction with its past-tense narrative of “what happened” was not sufficient for her purposes, which tended toward a more generalized present-tense analysis of “what happens.”13 She wanted to write fiction, but her worldview demanded exposition. What emerged was a hybrid product that combined fabricated plots and characters based on her own experiences and observations, heavily laden with social commentary. Thus, she dubbed her stories “too serious.” Of course they were serious, because they carried her message to the world about the status of her gender; they were loaded with her moral conviction of wrong, which she could not express openly, even to herself, and so must camouflage in fiction. The second point to emerge from Miles’s statement is that in her own person she offered a perfect example of the cause she crusaded for. “Perhaps I shall acquire a lighter touch as the children grow older and the daily stress is somewhat relieved.”

Miles placed her first story, “The Common Lot,” in Harper’s Monthly Magazine in December 1908, where it appeared with three full-page illustrations drawn by Lucius Wolcott Hitchcock. It was the first of five stories by Miles that Harper’s would publish between December 1908 and November 1910. During this same period, notable authors such as William Dean Howells, Mark Twain, Rudyard Kipling, and Willa Cather were writing for Harper’s—thus putting Miles among heady company.

“The Common Lot” serves in many ways as her signature piece by probing the dilemma of the mountain woman’s lot in life: marriage versus spinsterhood. Sixteen-year-old Easter Vanderwelt examines the life of her married sister as she helps with the unceasing toil to meet the needs of the babies, the husband, the women themselves, the little house they live in. From tending the garden patch to milking the cows to nursing the ailing baby, sister Cordy confronts a new pregnancy and begins to mend the clothes that her last baby has barely outgrown. Death precedes birth, however, and Easter hears Cordy’s fatalistic declaration over her baby’s grave, “I’ve got no idy the next’ll thrive any better.”14 In a foreshadowing of her own plight years later, Miles has Cordy deliver the only prayer offered for her baby before its burial. Frequent pregnancies, the rigors of childbirth, and the specter of infant death define Cordy Hallet’s view of married life—and that of most mountain women.

With such a vision before her, Easter understandably fears marriage. Practicing the restraint that her times required, Miles can only imply that Easter’s fear is rooted in part in the sexual and biological demands of wifehood. Easter occupies the curious position, as many a rural child does, of having witnessed and assisted at births and deaths; she knows much of the elemental aspects of life. Yet the sex act and the workings of her own body represent mysteries that she is not sure she wants to fathom. Although she never verbalizes the cause of her worries, she shares her concern with Cordy. The sister replies, “You don’t need to be afeared. . . . You’d be better off with him [Allison, Easter’s suitor] than ye would at home, wouldn’t ye? Life’s mighty hard for women anywhars.” From this discussion and her own long consideration Easter comes to see that her choice is “slavery in her father’s house or slavery in a husband’s.” Harsh as such an assessment may seem, it depicts a woman’s view, unhampered by illusion, of what her culture has to offer. She ultimately chooses a husband and her own home, realizing that to refuse them means refusing “the invitation of life” and “the only development possible to her.”15 In so doing she has acknowledged the common lot of mountain women, and perhaps of rural women everywhere.

Miles softens her picture of woman’s toil and constriction with the promise of romantic love and spiritual fulfillment of sorts. Yet she persists in pushing the hardships to the forefront. Like other local colorists, she straddled a splintery fence between realism and romanticism. On the one side grew the rose and on the other the brier; their commitment to fidelity obliged local colorists to include both. Readers of the popular magazines, and consequently editors, seemed to prefer roses in their endings. Disturbing resolutions or indeterminate endings are rare exceptions in local color writing. Melodrama, defined as “an affirmation of a benevolent moral order in the universe,”16 is much more common.

In her presentation of the mountain woman’s experience, then, Miles runs the risk of uncovering the ugly, the lewd, the tragic. To ameliorate those revelations, she steps into most of her stories and works the details into a seemingly happy resolution. The reasons for her manipulation are more complicated than the mere satisfaction of reader expectation. We must remember that she was a crusader with an ideal worldview; in her personal life she summoned an eternally rebounding hope to help her cope with problems far greater than any she ever depicted in fiction. The stories become her wish-fulfillment of situations working out satisfactorily within the mountain culture. In her fictional sorties she spotlights the privation, subservience, and limitations of mountain women; but in her retreats she withdraws to the safety of compensations. The divisiveness in herself and her fiction probably swells from two factors. First, the mountain culture truly does offer rewards to women through the giving and nurturing of life, as Miles allows Easter Vanderwelt and her sister protagonists to see. And second, as spokesperson for her culture, Miles must bear in mind her personal relationship to the people about whom she writes; they are a proud and fiercely independent lot who look with suspicion at her work because it is alien to their largely oral culture. Her mother-in-law, Cynthia Jane Winchester Miles, allegedly remarked, “These here writers and type-writers will do to watch.” Is there any wonder that her daughter-in-law alternates her attacks with rewards?

As indicated earlier, “The Common Lot” in both title and subject matter can stand as Miles’s battle cry in her crusade. Almost all of the other stories are variations on its theme. In fact, the first seven published stories feature a girl or young woman as protagonist—one who faces the prospect of marriage or deals with the consequences of it. “The Broken Urn,” published in Putnam’s Magazine in February 1909, opens with two small girls already wearing the yoke of their gender, as shown in the play they engage in. They cook and clean in their rock playhouse; they piece quilt patterns from scraps of cloth cast off by grannies and cousins; and they talk of being married someday. But their paths are to diverge and their burdens to differ as they grow into womanhood. One stays on the mountain and marries her childhood sweetheart; the other weds the hotel proprietor’s son and leaves the highlands behind. Sarepta Kinsale’s battle with poverty, toil, and infant death is set against her childhood playmate’s wealth, idleness, and thriving baby. Yet Nigarie Stetson, the playmate who migrated from the mountain and formed a new life in a totally different culture, is the restless one, the malcontent. Sarepta is the character who grows into an “understanding of the quiet, unassailable dignity of her own position, and [learns] the intrinsic worth of usefulness as contrasted with the false value of unearned riches.”17

The story’s title comes from a quilt pattern that Nigarie and Sarepta as little girls had altered to make a whole vessel they called “the Friendship’s Urn.” Miles’s choice of “The Broken Urn” rather than “The Friendship’s Urn” as title suggests Nigarie’s incapacity to have a life filled to the brim as Sarepta can. Nigarie is the incomplete vessel that has no room for the pain and suffering Sarepta experiences, and also no room for the sublime happiness that is Sarepta’s as she fills her whole urn of life day after day with a mixture of the bitter and the sweet. Nigarie’s broken urn contains only fleeting moments of gaiety, only brief occasions of real usefulness, but she does offer the gift of life to Sarepta’s baby when she lifts him impulsively to her breast. “Why, he’s starved most to death. . . . I reckon you ain’t been able to nurse him. I wish I could—why couldn’t I?” It is her richest moment, this season in her friend’s humble home, where she coaxes a tiny life to blossom through the nourishment of her own body and receives in return nourishment for her soul. But it is not to last. Nigarie is the displaced mountaineer, one who longs to come home, but who cannot stay there when she arrives. In a moment of candor she confesses to Sarepta and her husband: “‘We’ve been everywhere, Sam and me. . . . I’ve lived at the sea-shore, in the West, and we had a winter in New York; but I always wanted, I think, to come back here—on a visit,’ she added the concluding words hastily, for she knew that no place on earth could hold her long.”18

As the restless Nigarie flits back to her adopted culture, and Sarepta realizes the value of her own simple life in comparison, Miles meticulously controls her story’s close. She describes the mountain girl’s new awareness in language that Sarepta would never use and in concepts that Sarepta would never formulate. Miles leads the reader carefully by the hand as she editorializes: “Later, she [Sarepta] might lose sight of the vision somewhat, for we are all as incapable of holding constantly to great thoughts as of putting such definitely into words; but when the trailing glories paled, here was a child, gloriously alive, to remind her that she had once been inspired with the profoundly rational courage of seeing things as they are.”19

The author’s over-control in the ending may grate on the sensibility of the reader who wants a more subtle resolution for her fiction. However, if she can accept Miles’s aim as an expository one, she will understand how the author is operating. Exposition is designed to inform, to instruct, to persuade—all purposes that fiction may also fulfill. But much fiction employs a chronological scheme to accommodate the narrative; and elements of plot, setting, character, and conflict convey the writer’s meaning. In exposition, analogical and tautological schemes carry the argument on a theoretical or general level, though specific illustrations and narrative anecdotes often exemplify points. When story and exposition converge, as in Miles’s quasi fiction, the structure has a narrative organization with an expository intent. “The Broken Urn” looks like, and is, a story, but Miles is first and last a teacher. As such, she must reiterate her point and moralize: “for we are all as incapable of holding constantly to great thoughts as of putting such definitely into words.” The narrative itself is her exemplum; the authorial commentary her sermon.20

As Miles parades her fictional women before us, we note the slight variations in their common lot. Two young women are matched with preachers, and in both cases, the outcome of the match is problematic. Averilla Sargent, the village flirt in “A Dark Rose” (Harper’s, February 1909), at first refuses Luther Estill’s proposal, but after a bit, she accepts him and vows to go with him as he preaches, to lead the singing, to show that she can be “good” for him. But the conversion comes too easily for Averilla and makes one suspect her sincerity. This manipulated ending raises other questions: Does Miles deliberately choose not to convince us of Averilla’s conversion? Does she see Averilla as a type for those women who have employed a ruse and lived it because they think they must in a male-centered world?

“Mallard Plumage” (Red Book, August 1909) gives us a young wife who has the audacity to rebel against her May–December marriage to old Preacher Guthrie, who has locked her into a staid, restrictive existence. She flees with her young love from her premarriage days, only to bear the child of the husband she runs away from. In a predictable turn at the end, old Guthrie is taken in by the young people and nursed until his death, which comes as a result of a fall suffered while pursuing the runaways. True to the local color formula, Roma and Atlas display “hearts of gold” in their final actions toward Guthrie, and he does the same when, on his deathbed, he gives them his blessing to marry.

“The Dulcimore” (Harper’s, November 1909) hands us a twist in the form of a mother-daughter conflict over an impending marriage, one that sounds much like Emma Bell’s experience with her own mother. Selina Carden has groomed her daughter, Georgia, for a life outside the mountains. She wants Georgia to study music, to find a mate different from those offered by the circumscribed mountain culture. But Selina’s ambitions for Georgia are to be thwarted by the same implacable fate that had thwarted her own twenty years earlier. The girl has, “while awaiting the Prince, unwittingly become bound to Return,” the mountain blacksmith who secretly whittles her a dulcimore because he knows she likes music.21 None of Selina’s pleas can change Georgia’s mind.

The mother felt as though striving in a nightmare with bending, splintering weapons. . . . Had she not fought this same losing fight once before? She had never forgotten the days and weeks before her own marriage; the struggling, resisting, calling to her aid all habit and tradition, all maidenly reserve and family pride—in vain. She had suffered in withstanding; she had suffered in yielding; and her suffering had not mattered in the least, would not matter now.22

In desperation she spills her own story, her own struggle, her own sacrifice. “One baby after another. Yet the babies were all that kept me alive. . . . It would be easy enough to die for a man; it’s hard to live for him—to give him all your life just when you want it most yourself.” The mother’s story wrenches the girl’s emotions, but it effects an opposite reaction from the intended one. Georgia recognizes why her mother has stayed in this hard life when she whispers, “Mother! Don’t you see, now—. . . Now you have showed me—what love is, what it means to us women.”23

Miles’s crusade becomes the more plaintive when one realizes that Selina Carden perhaps takes her words from Emma’s own mother, Martha Bell, when she warns her talented daughter, “You’re blinded. . . . You can’t see now; but when you wake up and find yourself dragged down to the level of his people, it will break your heart.”24 Emma may well have been recalling the parental struggle she faced in her determination to marry Frank Miles some eight years earlier, coupled with the truth she knows now about married life. Creativity frustrated, ambition suppressed, body and spirit worn thin—these are the costs of womanhood. In 1909 the author can only arraign “the great laws of the universe” for this biological and spiritual demand that pits woman against herself, giving her fulfillment on the one hand and privation on the other.

Miles shifts her focus somewhat in “Three Roads and a River” (Harper’s, November 1910), possibly her best-crafted story and certainly one of the most powerful. The marriage theme is still present, but it takes a backseat to dire poverty. Shell Hutson becomes a criminal out of bitter need. In debasing himself to commit theft, assault, and robbery to supply food for his starving family, he forfeits two of the mountaineer’s strongest characteristics: his pride and his independence. Sociologists have noted the mountain man’s reluctance to ask for help; he would prefer to suffer, starve, and even die rather than take charity. But Shell is responsible for children, women, and an aging parent. In Dreiser-like fashion Miles drags Shell and the whole family lower and lower—from the once proud and prosperous keepers of the toll road and ferry to shamed, destitute starvelings. Caught in a deterministic trap, old Zion, Shell’s father, the patriarch, believes himself morally responsible for the family. Reaffirming the mountaineer’s choice of death over such a life, he asks for—and thinks he receives—a sign from God, making him the implement to carry his family from misery to peace “jist over, jist over Jordan.” The poison added to the poke-stalk pickles is taken by old Zion almost like a sacrament and passed with the same reverence to his unwitting family. Only his daughter Nettie refuses to eat, fearing her nursing baby will take colic from the sour.

Appropriately Nettie is spared her father’s salvation by death because she is the only member of the family who has maintained hope for betterment in life. But Miles, with her usual penchant for inveigling a happy ending, is not content with letting Nettie and the baby live. She must bring in at the moment of Nettie’s greatest horror a rescuer in the form of the husband who had deserted her, pregnant and penniless, months before. Now just as Nettie discovers the deaths of all her family, Steve appears with sheltering arms, money, and a promise of a new start in a new town. Miles’s compassionate view of human nature and her fervent wish for a benevolent universal order explain why she invents a turn-around ending, but they do not justify it for the fiction.

Nettie’s words summing up her commitment to life provide transition into another of Miles’s topics: “We seed a awful hard time . . . but look like where the’ was little ’uns—nobody would aim to die.”25

“Little ’uns” populate much of Miles’s writing—their begetting, birthing, nurturing. They are an important part of her affirmation of life. In only one story, though, does a child serve as the central character, and she is a catalyst who effects positive changes in the adults she encounters. Scarcely a plotted story at all, “Flyaway Flittermouse” (Harper’s, July 1910) is an enthusiastic, if somewhat sentimentalized, celebration of primal innocence and goodness as vested in a toddler.

As a sidenote, this story, like several others by Miles, took its genesis from an actual happening. In July 1909, Emma’s two-year-old daughter Kitty wandered away from the other children on a quest for huckleberries. When her mother discovered her missing, an all-out search began. Eventually a young man who had been on his way to see his girl in the valley “appeared with the dirty, berry-stained, scratched & tangled little maid, very wide-eyed, in his arms. He had heard her crying, in a sand-flat towards Middle Creek.”26 And so Kitty’s escapade provided the outline for “Flyaway Flittermouse.”

Although the quality of Miles’s fiction varies, her crusade for women’s causes never tires. It marches through stories where the women are mere stereotypes, as in “The Home-Coming of Evelina” and “At the Top of Sourwood.” It entertains a skirmish in “The White Marauder” when the young wife shows more spirit than usual and even enjoys a momentary, though tainted, victory over the powerful men in her life. It pauses to reveal a relative equality between the elderly husband and wife in “Turkey Luck,” a parable that erases Miles’s usual life struggle and substitutes the local colorist heart-of-gold formula in the ending, in which husband and wife, unbeknownst to each other, give away both turkeys they had meant to have for their Christmas dinner. Without berating one another, however, they contentedly settle for “possum and sweet taters” and are happy in their knowledge that other families on the ridge will have good turkey dinners for Christmas!

While Miles’s women characters most often seem to be victims as a result of their cultural bonds, one woman manages to shake off those shackles in “Flower of Noon” (Craftsman, January 1912). The story is set during the wake and funeral of Harmon Ridge, a relatively prosperous landowner who is believed to have no direct heir. Miles highlights the interrelationships of the pious family members who crowd in to share the spoils. She pits a grasping, hypocritical pair of brothers and their wives against young Fan Walton, Harmon Ridge’s housekeeper and supposed confidante. Though Fan must face alone the suspicions and inquisition about Brother Harmon’s money, she is not without allies in the dead man’s widowed sister and his young hired hand. Had Fan Walton been what she appeared, a housekeeper, she might have merely paid her respects to her former employer and walked away. But she was clearly more than that, and much of the story’s tension grows out of just what her relationship with Harmon Ridge was. The reader’s first hasty conclusion is that they were lovers, or maybe husband and wife; but young Byron Standifer’s obvious romantic devotion to Fan complicates that notion. Finally, in a confrontation where the family members demand to know her rights to their brother’s property, she yields her secret: “‘God’s my judge!’ she cried in a clear ringing voice. ‘Can’t you all see?’ And in her strong features, her firm neck and square-set shoulders so like those on which they had looked their last an hour ago through the glass of a coffin, they read the answer.”27 Playing on understatement to strengthen her story, the author gives only vague hints about the girl’s background before coming to her father; but the discomfited relatives are well aware that they have lost a farm and gained a niece.

Miles revels in Fan’s victory but restrains the impulse to flaunt her woman triumphant. In fact, the ending of this story demonstrates greater fictional art than do several of the others. Fan is clearly a woman in control, a propertied woman, generous and caring, as illustrated by her invitation to her widowed aunt to move her family into Fan’s home. She is confident and comfortable in her relationship with Byron. She is the one woman in all of Miles’s fiction whose promise of fulfillment in love is not compromised by self-effacement. As such, the story does not rely on the oft-used expository techniques of authorial comment and reader control. In woman’s victory, in her emerging personhood, Miles can afford to loose her grip and allow her crusade to find its own momentum.

The circuitous paths of Emma Bell Miles’s writing, then, always lead back to one center: woman. Perhaps Miles set out to portray the larger scheme of Southern mountain folk culture, but as she molded her material, one aspect of it continually pushed to the forefront. A teacher by inclination, a crusader by moral necessity, she devoted the bulk of her life’s work to demonstrating how mountain woman’s inevitable lot of “service and of suffering . . . refines only as it is meekly and sweetly borne.” Rejecting the “moonshine and rifles” that sent Murfree’s and Fox’s popularity soaring, she elected to deal with the serious, to advance a social criticism, though she felt compelled to camouflage her campaign beneath her stories of romantic love. The social criticism’s dominance so controlled her form that she evolved something more than or different from fiction. I have chosen to call it quasi fiction because of its definite aim to convince and persuade. With this kind of motivation and with her subject matter at her doorstep, Emma Bell Miles could follow only one course with her corpus of work: a record of the life of mountain woman, as she knew and lived it.

Notes

1. Four volumes of Emma Bell Miles’s original journals are housed in the Jean Miles Catino Collection of Special Collections, Lupton Library, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. A copy of a fifth volume is also there; the original of that volume is in the Chattanooga Public Library in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Thanks to the work of editor Steven Cox, Special Collections Librarian at UTC, an edited print edition of the journals was published in March 2014. Steven Cox, ed., Once I Too Had Wings: The Journals of Emma Bell Miles, 1908–1918 (Athens: University of Ohio Press, 2014), 22.

2. Emma Bell Miles, The Spirit of the Mountains, A Facsimile Edition (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1975), 69, 66. This is Miles’s best-known work, first published in 1905 by James Pott & Company, and republished in 1975 in the facsimile edition cited above.

3. Cox, 192.

4. A collection of Miles’s poetry, Strains from a Dulcimore, edited by Abby Crawford Milton, was published by Bozart Press in 1930, eleven years after Miles’s death. The collection contained all of the poems previously published in Chords from a Dulcimore, as well as others that had appeared in magazines and newspapers.

5. Cox, introduction to Once I Too Had Wings, xlvi–xlvii. The $25 Miles says she received for “a Madonna story” may have been a reference to “A Dream of the Dust,” published in The Lookout, although the date of that publication does not coincide with the journal date; the story, however, could certainly be described as “a Madonna story.” When she writes in September 1916 that she sold “A Mess of Greens” to Mother’s Magazine, that is likely the story that appeared under the title “The White Marauder” in August 1917; a mess of greens figures prominently in the plot.

6. See, for example, Harry R. Warfel and G. Harrison Orians, introduction to American Local-Color Stories (New York: American Book Company, 1941); Claude M. Simpson, introduction to The Local Colorists (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1960); Robert E. Spiller et al., “Delineation of Life and Character,” in Literary History of the United States: History, 4th ed. rev. (New York: Macmillan, 1974).

7. Warfel and Orians, xxiii.

8. Emma Bell Miles, letter to Anna Ricketson, March 4, 1907, Chattanooga Public Library, Chattanooga, Tennessee. Ricketson lived in New Bedford, Massachusetts, and had become a friend to Miles following the publication of Miles’s poem, “After Reading Thoreau.” The two corresponded until near the end of Miles’s life, though they never met in person. Emma’s letters to Ricketson have been preserved; forty-four originals are in the Chattanooga Public Library.

9. Emma Bell Miles, letter to an unnamed correspondent, dated January 15, 1913 [1914], Hindman Settlement School Archive, Hindman, Kentucky. Facts within the letter and contextual evidence indicate the date should be 1914. I am grateful to Professor David Whisnant, retired from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, for unearthing the Hindman letter and sharing it with me.

10. Henry D. Shapiro, Appalachia on Our Mind (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1978), 18–31. The following sketch of Appalachia’s people is partially based on Shapiro’s study. It is necessarily simplistic because of the brief space I have allotted to it.

11. Miles, letter to Anna Ricketson, April 5, 1907.

12. Miles, letters to Anna Ricketson, March 31, 1907; April 5, 1907.

13. I have adopted James Moffett’s terms from “Kinds and Orders of Discourse,” in Teaching the Universe of Discourse (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1968).

14. Emma Bell Miles, “The Common Lot,” Harper’s Monthly Magazine 118 (December 1908): 149.

15. Ibid., 151, 152, 154.

16. John G. Cawelti, Adventure, Mystery, and Romance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976), 262.

17. Emma Bell Miles, “The Broken Urn,” Putnam’s Magazine 5 (February 1909): 580.

18. Ibid., 578, 579.

19. Ibid., 580.

20. Miles most likely used her sister-in-law Laura Miles Hatfield as model for the young mother who could not adequately breastfeed her baby. Laura and her husband suffered the loss of several infants, all of whom are buried in a row in Fairmount Cemetery in Signal Mountain, Tennessee. One of these was named for Emma.

21. Emma Bell Miles, “The Dulcimore,” Harper’s Monthly Magazine 119 (November 1909): 952.

22. Ibid., 954.

23. Ibid., 954, 956.

24. Ibid., 953.

25. Emma Bell Miles, “Three Roads and a River,” Harper’s Monthly Magazine 121 (November 1910): 889.

26. Emma Bell Miles, Journal, I, July 1909. Cox, 39.

27. Emma Bell Miles, “Flower of Noon,” The Craftsman 21 (January 1912): 394.

Emma Bell, age twenty-one, shortly before her marriage (photograph in editor’s collection; also in Jean Miles Catino Collection, Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Frank Miles, age twenty-three, about the time of his marriage (Jean Miles Catino Collection, Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Emma Bell Miles with husband Frank and twin daughters, Judith and Jean, in front of their tent home, summer 1903 (photograph in editor’s collection; also in Jean Miles Catino Collection, Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Emma with children, Judith, Kitty, Joe, and Jean, outside the home Frank built, summer 1908 (photograph in editor’s collection; also in Jean Miles Catino Collection, Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Emma, the twins, and friends from Chattanooga who had come to visit on Walden’s Ridge, about 1910 (Jean Miles Catino Collection, Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Emma and her youngest children, Mirick (Mark) and Kitty, summer 1911 (Jean Miles Catino Collection, Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Emma and the twins, Judith and Jean, summer 1913 (photograph in editor’s collection; also in Jean Miles Catino Collection, Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Emma, probably 1914, age thirty-five—newspaper advertisement for a lecture author was giving (photograph in editor’s collection; also in Jean Miles Catino Collection, Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

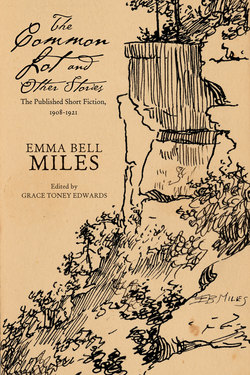

Pen-and-ink sketch of the bluff on Walden’s Ridge by Emma Bell Miles (Jean Miles Catino Collection, Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Pen-and-ink postcard sketch of a cabin on Walden’s Ridge by Emma Bell Miles (Jean Miles Catino Collection, Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Watercolor of a cabin and attached fence on Walden’s Ridge by Emma Bell Miles (Jean Miles Catino Collection, Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Pen-and-ink postcard sketch of an open fireplace with cooking pot on Walden’s Ridge by Emma Bell Miles (Jean Miles Catino Collection, Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Watercolor of a girl cooking over an open fireplace by Emma Bell Miles. Daughter Judith posed for this painting, which was used in the individually illustrated copies of Chords from a Dulcimore. (Jean Miles Catino Collection, Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Pen-and-ink postcard sketch of a cabin under the hillside by Emma Bell Miles (Jean Miles Catino Collection, Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Watercolor of a fern and a pink lady’s slipper by Emma Bell Miles (Jean Miles Catino Collection, Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Handmade greeting card in watercolor by Emma Bell Miles (Jean Miles Catino Collection, Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Illustration by Lucius Wolcott Hitchcock for Emma Bell Miles’s first published short story, “The Common Lot,” in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, December 1908: “On the Mossy Roots of a Great Beech She Awaited His Return”—Easter sitting by the tree waiting for Alison (Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Illustration by W. Herbert Dunton for “The Dulcimore,” published in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, November 1909: “He Fired the Mass, Pulling Regularly on the Bellows”—Georgia and Return in the blacksmith shop (Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Illustration by W. Herbert Dunton for “Flyaway Flittermouse,” published in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, July 1910: “D’You Reckon She’s Lost, Jeff?”—Flittermouse with two of the adults she meets in her travels (Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)

Illustration by Howard E. Smith for “Three Roads and a River,” published in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, November 1910: “Secretly Adding the Contents of the Bottle”—Old Zion acting on what he thinks is his sign from God (Special Collections, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga)