Читать книгу The Common Lot and Other Stories - Emma Bell Miles - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеpreface

I first came to know Emma Bell Miles and her work almost four decades ago. Shortly after the 1975 launch of the facsimile edition of The Spirit of the Mountains, a friend gave me a copy of the book just as I was heading to the University of Virginia to begin work on a doctorate in English language, literature, and pedagogy. With no time for extra reading, I shelved it along with many others and plunged into a rigorous load of literature and folklore courses. Scarcely a month later, my folklore professor, Dr. Charles Perdue, carried in a copy of The Spirit of the Mountains to ask if I knew the book. When I confessed that I owned a copy but had not read it, his admonition was, “Read it!” Always the dutiful student, I went straight home and started in. From that moment on, I’ve been hooked on Emma Bell Miles!

When the time came to propose a dissertation topic, I knew Emma was my girl—provided I could convince my advisors that she was worthy of study. By then I had learned that she wrote not only the fictionalized ethnography about Walden’s Ridge, Tennessee, but she also wrote poetry, short fiction, a book on birds, newspaper columns, and more. I had also learned through the help of Chuck Perdue and Dr. David Whisnant, then at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, that four of Miles’s children were alive and well in various parts of the country. I set out to interview her children and people who had known her in Chattanooga and on Walden’s Ridge (now Signal Mountain and Walden). I intended to find everything she wrote that was “out there,” to synthesize and analyze, and ultimately to put it all together in a literary biography.

My research moved from phone calls and letters to scheduled visits—first to Miami, Florida, where daughter Jean Miles Catino lived. With family in tow, including a rambunctious two-year-old son, I spent a couple of days talking, listening, taking notes, sifting through photographs, admiring art work—both Emma’s and Jean’s—and enjoying Jean’s beautiful orchids. Like her mother, she had developed a talent for painting and a love of nature, which manifested itself through the cultivation of dozens of varieties of orchids. Upon our departure, Jean presented me with a lovely hand-crocheted pink afghan in anticipation of the arrival of my second baby, who she predicted would be a girl. Months later I wrapped my bouncing baby boy in the pink afghan simply because it came from the hand of the daughter that touched the hand of the author and artist I so admired! To this day I still cherish the gift and am apt to carry it along to show it off whenever I have opportunity to lecture about Emma Bell Miles.

My second major visit was to the home of the other twin daughter, Judith Miles Ford, in Aline, Oklahoma. Because she lived, as she put it, “out here in the middle of the prairie,” she insisted that I stay in her home. (I went sans family this time.) For three days and nights, I lived, breathed, ate, and slept Emma Bell Miles! Judith was such an avid advocate for her mother’s work that she plied me with abundant material: her own memories and stories; letters and newspaper articles, both by and about her mother; magazine articles; pieces of artwork; and most important of all, her mother’s original journals. At that time she had in her possession four volumes of handwritten journals, kept in what looked to be worn account ledgers. A fifth volume was a typescript of the original that had somehow made its way into the Chattanooga public library. These journals covered the years from 1908 to 1918. Believing them to be of great value, Judith was eager to share the journals with me, but only in her home under her watchful eye! Needless to say, I was ecstatic to see these original documents and willing to use them under any restrictions she imposed. She allowed me to take copious notes and to read some segments into a tape recorder so that I could include direct quotations in my writing. Later, after I returned home, she sent me photocopied segments of the journals that I especially wanted to access. She also gave me multiple pictures of her mother and other family members with permission to use them in the dissertation I was writing. I am eternally grateful to Judith for the generosity and hospitality she showed me on that visit and in the communications we had thereafter.

Initially I had planned to fly to California to visit the two younger Miles children, Joe and Kitty, who lived in San Diego and Ventura, respectively. But after phone calls with all four, we mutually agreed that this expensive trip was unnecessary. Joe and Kitty anticipated being of minimal help in light of the deeper knowledge of their older sisters. In retrospect, I wish I had gone, for as I have learned more through the years, I know both would have had fascinating life stories to tell.

Nevertheless, my research travels were by no means over. Kay Gaston, then of Signal Mountain, Tennessee, had been studying and collecting Miles memorabilia for years. She was a tremendous help in sharing her knowledge and collection and in taking me to meet various other people in the area who had known Emma personally or who had collections of her artwork. In the many years since then, Kay has continued to be an inspiration through her own writing and lecturing about Miles. Kay’s home on Signal Mountain was but a twisty mountain road away from Chattanooga, where I found a treasure trove of forty-four letters written by Emma Bell Miles to her friend Anna Ricketson in New Bedford, Massachusetts. These were housed in the Chattanooga-Hamilton County Bicentennial Public Library and provided a wonderful record of Miles’s life as she portrayed it to a long-distance friend between 1907 and 1917.

Other research stops were the Tennessee State Archives in Nashville, where a few Miles poems resided, and finally the Library of Congress in Washington. My goal in our national library was to discover and make copies of everything Miles had ever published—a task much easier said than done! I could find the stories, poems, and articles in major magazines such as Harper’s, Lippincott’s, and Century, but the smaller unindexed publications were another matter altogether. Because I had only approximate titles and dates gleaned from journal entries and occasionally letters, I gained permission to go into the stacks of the Library to search through multiple volumes of publications such as Nautilus and Mother’s Magazine. I have fond memories of sitting flat on the floor in the Library of Congress between tall shelves of musty periodicals, leafing through bound tomes, searching for the name of one almost unknown writer from the mountains of East Tennessee. When I found something, my inclination was to jump up and shout in those hallowed basement recesses, but I restrained myself out of respect for another scholar who might have been laboring in some secluded corner.

At long last in 1981 a dissertation emerged, and one might have thought my Emma Bell Miles immersion had ended. But that was by no means true. In the thirty years that followed, I introduced hundreds of students to Miles’s work in various courses I taught at Radford University. I wrote and published several articles about her over the years and had the pleasure of guest-editing the Fall 2005 edition of Appalachian Heritage devoted to the centennial celebration of the publication of The Spirit of the Mountains. I have delivered innumerable lectures and slide presentations about Emma in venues far and wide and continue to do so today.

Multiple other scholars have also maintained interest in this remarkable Appalachian mountain woman whose lifespan was far too short. (She died at age thirty-nine.) In recent years notable efforts include the work of Czech scholar Dr. Katerina Prajznerova of Masaryk University in Brno, who has written extensively about Miles, particularly her interest in nature and the environment. Steven Cox, Director of Special Collections at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, has worked for years to amass a wonderful collection of Miles materials and in 2014 published excerpts from her journals through Ohio University Press. George Brosi, former editor of Appalachian Heritage, and wife Connie have long been advocates for Miles and have written articles about her. Lincoln Memorial University sponsors a biennial Emma Bell Miles lecture and an annual Emma Bell Miles essay contest at its Mountain Heritage Literary Festival. The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga and Signal Mountain friends periodically put on symposia and other events to honor their renowned author and artist. The list could go on, for her appeal does not wane.

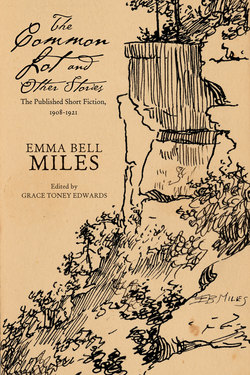

My own ambition for many years has been to make Miles’s fiction available to the public. Other works have been reprinted, including The Spirit of the Mountains, Our Southern Birds, and Strains from a Dulcimore, but her stories have remained virtually hidden in musty magazines and scarcely accessible library stacks. In this collection all seventeen of her known stories have been brought together in chronological order of their publication, ranging from 1908 to 1921. I have transcribed the stories primarily as they were published in the original periodicals, maintaining Miles’s spelling and punctuation. The one concession made for modern readers has been to close up spaces in contractions to eliminate inconsistencies in the original publications, sometimes even in the same story. For each story I have identified the source and date and have written a brief editor’s note as a guide to readers who may desire such.

Though writing styles and subject matter have changed significantly over the hundred years since most of the fiction came to print, there is a wealth of cultural and biographical context to be gleaned from these stories. This book achieves what feels like a lifelong quest for me and fulfills a promise made long ago to the spirit of the artist who created the fiction. I am greatly pleased to bring Emma Bell Miles and her work into the twenty-first century.

Grace Toney Edwards

Christiansburg, Virginia

October 2015