Читать книгу The Common Lot and Other Stories - Emma Bell Miles - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеtwo

The Broken Urn

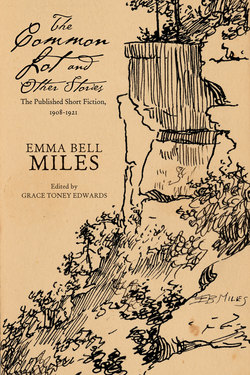

From Putnam’s 5 (February 1909): 574–80; illustrated by Alden K. Dawson

Continuing the theme of woman’s common lot, “The Broken Urn” opens with two small girls already playing out their expected gender roles in their rock playhouse: cooking and cleaning; piecing quilt patterns from discarded quilt scraps; and talking shyly of eventual marriage. But as adulthood approaches, their choices take them in different directions. Sarepta, the quiet beauty of the pair, remains in the mountain community and marries her childhood sweetheart. Nigarie, the adventurous one, leaves the mountain in the company of her husband, the hotel proprietor’s son. The contrast in their adult lives provides the conflict around which this plot turns and offers an explanation for the author’s choice of title: “The Broken Urn,” after the quilt pattern that serves as metaphor for the story.

. . .

Above the cabin, in the edge of the clearing, stood a great irregular block of sandstone. Gaunt and barren it may have been, as first fallen from the cliffs that towered behind the forest; but centuries of weather had made it a thing of friendliness and comfort. Succulent grasses, rooted in the loam accumulated by the yearly drift of fallen leaves, sprouted from every crevice; ferns trembled over its edge; the fence led only to the rock on either side, so that its bulk interposed to spare the mauling of several dozen rails; a hollow scooped under it on the woodland exposure afforded shelter in winter to any number of pigs; and beneath the overhang facing the valley two little girls had built a playhouse. Here signs of frequent occupancy were not lacking: the ground was lightly printed all over by slim bare feet, and the rock was smudged with woodsmoke above a tiny furnace of stones. No real playthings were visible, but the rock shelves were stocked with potsherds and broken crockery, and there were tin pails and even little skillets and cookers, cleverly fashioned from old tin cans, for the making and serving of real bear-grass salad.

It was, however, too late in the season for bear-grass. The tide of young summer had brimmed the valleys, and came rushing up the slopes to burst along the bluffs in a high-flung surf of laurel bloom. The two small friends were seated now on the grassy top of the rock, shaded by a great arching tupelo; they were piecing quilt patterns. They had laid out for comparison on their knees and about on the grass, the Eagle, the Dream, the Texas and Kentucky Stars, the Crazy Ann, the Tree of Paradise, and three or four varieties of brick-work and log-cabin. The pattern under immediate consideration was the Broken Urn.

“I been a-studyin’,” said Nigarie, the sprightly, dark one, “whether hit wouldn’t be the prettiest to piece the urn out whole.”

“Let’s try hit that-a-way,” agreed Sarepta, a child with an angel’s face.

Against nature, the beauty was also the worker, and Sarepta’s small skilled fingers swiftly cut and laid out in pink and brown calico the design they had mentioned, her big gray eyes shaded by sumptuous lashes, brooding full of tender dreams above a tangle of flaxy-gold curls falling about the down-bent, intent face, pure in outline and tint as a pearl.

Even loquacious Nigarie sat acutely observant, scarcely speaking, her three-cornered kitten countenance with its hard, round little cheeks under the beryl-green eyes puckered to disproportionate anxiety, till the urn was an accomplished fact, so absorbed were they both in this, their one avenue of artistic expression.

“Hit’s some like grandma’s Vase of Friendship,” commented Nigarie, drawing a long breath when it was done.

“We could call this the Friendship’s Urn,” suggested Sarepta, timidly. Nigarie usually did the suggesting for the pair.

That small person now ran a reckless hand to the bottom of her basket and plowed up her collection of scraps. “This rosebud sprig’s the prettiest I’ve got. Hit’s a piece of Easter’s weddin’ dress,” she volunteered.

“I’ve got one block all pieced outen scraps Easter an’ Ellender given me,” Sarepta showed it.

“I’ve got one made all outen the boys’ shirts, and some over,” Nigarie tossed her braids. “Harmon’s and At’s, and this pink stripe’s Macon’s, and this ’n’s Joel’s, and here’s Mart’s; and hit’s set together with Sam Stetson’s.”

“Sam Stetson’s!”

“Cert’n’y; I reckon Sam Stetson ain’t none too good to have a piece of his shirt in my quilt if his pappy does keep the hotel, an’ he is goin’ to school in the settlement. I wish’t I could swap you out of that blue gingham, Sarepta. I want hit to go with this sprig weddin’ dress.”

“I’ll—I’ll let ye have it all for—for that one.” The gray eyes glowed as she indicated the pink striped scrap from Macon Kinsale’s shirt—and she cherished it tenderly, tucking it jealously deep in the bottom of an orderly basket when Nigarie willingly exchanged it for the blue gingham.

The trade effected, they sewed busily.

“That’s goin’ to be plumb pretty,” commented Sarepta at last, leaning to look at her friend’s work. “Do you reckon you ’n’ me ’ll ever—make us a weddin’ dress?”

The sweetest imaginable color crept over both little faces, and shining eyes were bent swiftly to their needlework.

Sarepta’s fingers stole toward the pink striped scrap in her basket.

“Mine’ll be silk,” said Nigarie confidently.

It was even so. . . . All through the years, Nigarie was shielded, favored. As an only child, she went to school while Sarepta was fulfilling at home the duties of the eldest girl in a large family. Work was found for Nigarie at Stetson’s summer hotel, and when she came home it was to make ready for her marriage to the proprietor’s son, Sam Stetson. Sam was in business now in a flourishing little city, and doing well. Nigarie promised to write often to Sarepta; but soon the letters became fewer, and after a time they ceased.

Even while there was communication, Sarepta had slight understanding of Nigarie’s social evolutions, as described in occasional newspaper clippings enclosed. Statements about refreshments, decorations and costumes conveyed little meaning to a mind accustomed to clothe its thoughts in the antique dialect of the mountains. But she made out that the wedding dress and several others were indeed of silk.

She was not disturbed by that, for she could dwell on her own wedding, when she came down-stairs, shining with a mysterious happiness, in her lawn and cheap ribbons, to find the big log sitting-room filled to overflowing with her kin. She had tremblingly given her promise to love, honor and obey, and had kept it, with a willing spirit if not always to the letter. But Macon’s “protect and cherish”—well, as a true wife she never permitted herself to form any conclusion as to whether it had been forgotten five minutes afterward. Macon had done the best he could; as time went on she reiterated that to herself almost fiercely. He had done the best he could!

After the first infare with their meagre furnishing to a cabin on his uncle’s land, they had moved, in seven years, nine times, from shack to cabin and from cabin to shack, hounded by poverty and circling like stags as close to home as possible. Macon had indeed done his best; but Sarepta, whose wants were so few, had to pinch in ways she considered hardly decent. She had always lived on little; she learned now to live on next to nothing. She ate food which she had always regarded as fit only for pigs or chickens. Her mind was occupied, not occasionally but constantly, with problems that were like gravel in a shoe, as insistent as they were contemptible: “If I divide this inch of pork, will it season Macon’s potatoes for supper and again at breakfast? If I pick a mess of sarvices to-day, have I got sugar in the house to make a cobbler for Sunday dinner? Can I, by piecing Macon’s shirt sleeves, and lining the yoke with flour-sacking, get enough out of this gingham to make me a sunbonnet?”

Women always get the worst of poverty. And Sarepta was no miser by nature. Some wives eat the biscuit end of the pone and the skin of the meat because they are afraid no one else will; she chose them because she could not bear that any one else should have to.

Again and again they strained every nerve and sinew to win a shack and clearing of their own, only to be disappointed. Every time, just as the signing of the deed seemed a probability of next week, something happened—a drought on the garden, a murrain on the cow, or another baby. Three of these had come—and gone—leaving no more visible impress than a little less elasticity of Sarepta’s figure, a little deepening of the shadow behind her beautiful eyes; for each, after a few weeks of ineffectual striving to digest the cows’ milk which the poor mother was obliged to give it, had quietly straightened out in her arms and died.

The fourth was three weeks old and already ailing, on the day of Nigarie’s return.

Sarepta heard the news from a neighbor woman who shared her tubs and huge pot and did washing for the hotel people. Nigarie’s fat baby, her airs and her summer wash frocks were subjects of an intermittent conversation that went on all morning below the spring in the hollow. The mountain woman’s beauty one might almost say was undiminished by her hard life. In the limp unlovely frock it shone out a luminous, incongruous fact. No one seeing her, pounding away at the bat-block and replying with mild monosyllables to the rhapsodies of the other, would have guessed that she was almost sick with terror lest this last puny life slip also out of her grasp. A woman must learn to chatter of other things, lest the gods take notice and in pity slay.

It was the first of April—beautiful weather, but the hard time of year, when the hungry winter has gnawed the last scraps of pork rind from the smoke-houses of well-to-do farms, and the small fruit and truck-garden have not yet begun to relieve the poor. Sarepta was dreading the approach of hot weather on the baby’s account; yet she was wondering how to round out a good dinner for Macon from bulk pork and meal. As she carried the last of the wash up to hang it out on the fence, she saw the flicker of a white dress moving along a woods-path. Some one was coming to see her—some one fashionably attired, yet carrying a baby on her hip like any mountain woman! Then she recognized Nigarie.

She stood and trembled, without a word to say, abashed not at all by Nigarie’s finery, but because she did not know on what ground the visitor would meet her.

Transgressing all mountain custom the new-comer flew at her with a little laughing cry and kissed her on the cheek.

“My, ain’t you pretty yet!” she said half enviously as she entered the cabin. “I’ve been to the bear-grass rock—remember, Sarepta?” Nigarie’s bright eyes were full of misty recollection as she untied the baby’s cap. “It’s just like it used to be,” she said thoughtfully. “Funny how things stay, and we change. I filled Sammy’s apron full of bear-grass; shall we have a sallet for dinner? Where’s your baby, honey?”

With a catching of the breath that was almost a sob, Sarepta brought out the thin little occupant of her cradle. Without a word she laid it across Nigarie’s knees.

The little creature began to wail feebly, and before his mother could take him and hush him, Nigarie, moved by what impulse of immortal compassion who can say, lifted him to her breast.

“Why, he’s starved most to death,” she said gently. “I reckon you ain’t been able to nurse him. I wish I could—why couldn’t I?” She broke off and laughed in her usual elfish inconsistent fashion. “Sammy pesters me most to death,” she said with apparent irrelevance. “There ain’t any fun stayin’ at a hotel with a baby. I’ll bet I’ll never try it again. As soon as he’s old enough I’m going to leave him with Mother Stetson. He’s so spoiled he wouldn’t do anything but holler if you put him down.”

But skilled Sarepta had taken the fat little new-comer with his royal airs of kinghood and disposed him on a quilt upon the floor. Smilingly, silently, she furnished him with a green switch, and attracted the cat’s attention.

“Well, you are a wonder,” Nigarie said—“but then, you always were. I’m sick of the hotel—do you reckon you could board me for the rest of the time I want to stay? It would be like the old days—and you could take care of Sammy when I wanted to go somewhere.”

Sarepta on her knees looked up at the ruling spirit, sitting above her, nursing her baby, and a mighty gratitude, a wordless emotion which she could not for the life of her have expressed, shook her from head to foot. Here, then, was the answer to her prayers.

“I’ll make you as comfortable as I kin,” she managed finally to say. “We’re mighty poor folks—but you know that—you heard it over at the hotel before you ever put foot in this house. Oh, Nigarie, if you would only stay with me a while!”

And so the butterfly woman, the little cuckoo who never wanted a nest of her own, folded her wings for a season in this humble place. She nursed Sarepta’s baby as she nursed her own. The envious eyes of the mother were on her as the little fellow’s thin body rounded, and the puny limbs grew stronger. To Sarepta it seemed almost a miracle from heaven, and the little cabin a holy place.

The days were filled with a deep peace and vital joy. Nigarie was happy in having some useful work, or rather in being herself actually necessary to the daily welfare of others; Sarepta, in watching her child grow, in the presence of a dear and merry companion, and in seeing Macon take that long-looked-for “start.” For he, profiting by Nigarie’s presence, secured work with a valley farmer, and began working out the purchase of some two acres of land. He came home every Saturday night, carrying on his back provisions for the coming week, and left before day on Monday morning. Hence Sunday was the white milestone of the week to both women; for Macon was gifted with temperament and charm.

Sarepta’s kitchen outfit was hardly less crude than that of the playhouse had been, yet she always contrived a little feast for his day at home. Talent he had, too. All the long still afternoon and after the moon had climbed above the mountain he sat on the porch, his chair tilted back against the house-logs, and played upon the banjo. He played, and set the whole fragrant night throbbing, until their only neighbors, among the pines far up the height, sat listening too, in another cabin door; played until the two mothers, the long-continued rhythm going to their heads, sprang up, took hold of hands and danced together like two girls over the shaking puncheons; played until the spiders peeped out from the roof-boards to hear, and the whippo-wills came right up to the fence and thrilled the night with their wild jodeling. And in truth his music was hardly less eerie than theirs; a barbaric jangle, interspersed with strange rocking whoops and calls, and elaborated with curious fingerings—snaps and slides and twangs unknown to banjo-players outside the mountains.

There were in it tone-pictured incidents of cabin life, and echoes of the larger enfolding life of nature—murmuring undertones as of drumming rain, ghostly half-whispered minors, and long chuckling meditations mellowed as if by the product of hidden stills. He sang too in the excellent baritone of the mountaineer—not the elder ballads which girls delight in and mothers croon, but man-songs—real folk-song of raid and foray, rollicking drinking-songs, with boast and challenge, and peculiar baying rhythms that reached a climax in the long-drawn hunting-yell.

Some of this music was known to his hearers; some, unacknowledged, was his own composition or improvisation. Nigarie had heard better in theatres, of course, but this was knit in with her earlier recollections. To this every fibre of her being responded as to the dramatic element—breath of sweet keen frost or exultant storm.

She had not known such contentment since she left the mountains.

“We’ve been everywhere, Sam and me,” she remarked one evening as the three sat together in the dark. “I’ve lived at the sea-shore, in the West, and we had a winter in New York; but I always wanted, I think, to come back here—on a visit,” she added the concluding words hastily, for she knew that no place on earth could hold her long.

In the fall Nigarie Stetson returned to her own life. Those restless, wayward, eager feet went back to seek new paths—and yet new ones. Sarepta watching her departure through tears that were not all bitter, a round, rosy baby on her shoulder, knew somehow that the visitor would never return. And she wondered at herself meekly. Where was the bitterness of loss, where the canker of envy she had once thought to endure when this moment arrived?

She turned a thoughtful face and kissed her child. She entered her small dun dwelling and looked about at smoke-browned beam and rooftree with new eyes. She began to realize that in the unhurried, intimate conversations of those long summer days she had come into an understanding of the quiet, unassailable dignity of her own position, and learnt the intrinsic worth of usefulness as contrasted with the false value of unearned riches. She felt dimly and half unwillingly, as she contemplated Nigarie’s lot, that there was something almost disgraceful about being “kept” in soft and delicious idleness. Even the remembrance of the three starved babies was no longer a bitterness. Surely it were better to have borne and loved and lost them, every terrible, precious memory of them, than to bear the burden of feverish apprehension which Nigarie evinced toward motherhood itself; to speak continually and openly of the baby as an unearned burden.

She established her boy in his cradle, preparatory to taking up her work. She was suddenly full of a zest for life to which her days had long been stranger.

Macon, having completed his purchase of land, was now busied near home, hewing logs for a cabin of their own. By way of doing his best he had come into the house, ostensibly for a drink, but really to try a new tune on his banjo. At some political meeting the phrase about “dipping the pen in gall” had caught his fancy and suggested to him a new couplet to which he was tentatively fitting an air:

“I dip my pen in golden ink, to write my love a letter,

And tell her that most every day I love her a little better.”

The nearly perfect monogamy of the region renders it unlikely that a mountaineer compose verses in honor of any but the one woman. As his wife came in Macon tossed the new song at her with a half humorous, but wholly gallant bow.

She laughed, as it seemed to her, immoderately—there was so much to laugh at! She turned once more to the babe in the cradle; how rosy he was, and how he laughed, too. She went, on feet that love made light, to prepare her dinner of herbs.

Later, she might lose sight of the vision somewhat, for we are all as incapable of holding constantly to great thoughts as of putting such definitely into words; but when the trailing glories paled, here was a child, gloriously alive, to remind her that she had once been inspired with the profoundly rational courage of seeing things as they are.

And on the cradle, pieced by Nigarie in the summer mornings while both babies slept, lay a little quilt of the pattern they had named the Friendship’s Urn.