Читать книгу The Common Lot and Other Stories - Emma Bell Miles - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеone

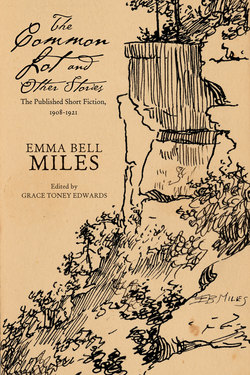

The Common Lot

From Harper’s Monthly Magazine 118 (December 1908): 145–54; illustrated by Lucius Wolcott Hitchcock

“The Common Lot” serves in many ways as the signature piece for most of Miles’s fiction. It is her battle cry for the crusade she is waging for the liberation of mountain women from the patriarchal culture they are forced to live in. The story probes the mountain woman’s dilemma: to take on the burdens of marriage and the cares of a household or remain a spinster and be condemned to much the same drudgery in the homes of others. Sixteen-year-old Easter Vanderwelt confronts the dilemma as she helps her married sister with the endless toil of caring for her babies, her husband, and the household, with little time to care for herself. Ultimately Easter must make her own choice between “slavery in her father’s house or slavery in a husband’s,” a decision that will determine the course of the rest of her life.

. . .

The big boy in the doorway was hot and dusty, but not tired. It was impossible to be really tired with running free on a morning when all the earth was awake and trembling with the eager restlessness of young summer. His head was carried high, with a deerlike poise; the dark young profile with its promise of early manhood flung up a challenge to greet the world. His gait all morning had been the wolflike pace by which the mountaineer swings the roughest miles behind him.

The woman—she was hardly the mistress—of the big log house was tired, however; she could scarcely remember a time when she had not been so. Life had resolved itself, for her, into conditions of greater or less weariness, and she had learned to be thankful if the weariness were not complicated by rheumatism or other pain. Her day was always long, her night was short; she had no time to think of the sunshine and roses in her own dooryard.

“I come apast Mis’ Hallet’s,” he explained his presence, “and she stopped me to send word that she wants Easter to come and stay with her a spell. I’ve got a note in my pocket, if I can find it.”

Mrs. Vanderwelt read the pencilled scrawl from Cordy Hallet, her married daughter. “Allison,” she began, a distressed frown puckering her lined forehead, “if you’re goin’ by the spring, would you just as soon stop and tell Easter? She’s churnin’ down thar. Ye might as well carry her a pokeful of cookies.”

She filled the boy’s hands with freshly baked saucer-wide cookies, scarcely more than sweetened soda biscuit-cakes, and put some into a paper bag for her daughter.

The young fellow might have chosen the highroad, but the sun-dappled path through the woods drew first his eyes and then his feet. Everything was in motion there, tilting and waving in the light breeze; dewdrops glittered still under the leaves; brilliant bits of insect life started out of the sun-warmed loam and rustled with many-legged creepings in last year’s dry leaves. On the way he cut a length of hickory, from which the sap-loosed bark could readily be taken, and walked on more slowly, shaping a whistle with his knife, and thinking of Easter, and their days in school. She was not so old as he by several years; perhaps she was not quite sixteen. He had scarce awakened to full perception of her girlish comeliness, but he admired her nervous agility and grace in play. She could run and climb, and play coosheepy and hat-ball, as well as any of the boys; that was his way of putting it to himself.

The spring was a dark pool, walled with rock and housed with a structure of logs and hand-riven clapboards. It had a shelf all round below the surface level, on which jars of milk stood in perpetual coolness. Easter, having finished her task, was nowhere to be seen; her churn stood outside, and new butter floated in a maple bowl of water, set on the rock to cool. Having tested his whistle and found to his delight that it would pipe three or four notes, the boy bent over the water for a while, his eyes caught first by the reflection of his own face and then by the leaping and stirring of sand and tiny pebbles where the vein rose through the bottom. He laid himself flat and drank deeply of the bluish cold water; then, closing the door of the spring-house against stray “razorbacks,” he began to look about in the woods. Once he called timidly, “Easter!” but the sound of her name in his own voice rather frightened him, inasmuch as he was not sure he ought not to put a Miss, or some such foolish handle, before it; and he proceeded uncertainly into the maple thicket below the spring, not knowing where to search. Then a gleam of blossom flashed between the boles, and he guessed that she would be there.

It was a white-flaming mass of azaleas, delicately rosy as mountain slopes of snow splashed over with the pink of dawn. In the midst sat a girl, drinking the overflowed sweetness of that dripping and blowing blank of flowers: now fingering single branches that lifted into the tender foliage their crowns and pompons, and now drawing all together down against her face in a sheaf of cool, pure petals—drowning her young senses in perfume. She had taken off her coarse shoes to plunge her feet into the dewy freshness of those ferns that in such maple-shaded hollows keep the azaleas company. Easter was too old to go barefoot, but not too old to delight in the feel of the ancient soil beneath her feet, and in the shining dewdrops on her instep’s blue-marbled satin. In after years, when the burden of responsibility bore heavily on her shoulders, she remembered that intermission among the flowers as her last taste of care-free pleasure, her last moments of childhood.

Suddenly, with a soft crash of rending growth, the boy parted the underbrush and came toward her. She gathered herself together with a swift instinctive modesty, tucking her feet under her skirt. “Howdy, Allison?” she greeted him, and “Howdy?” he answered, thrusting the bag of cookies at her by way of accounting for his presence.

She smiled in an embarrassed fashion as she took the poke from his hand. The thought of her bare feet made her unable to rise. The big boy dropped to the ground beside her. He delivered his message and watched her read the note.

“Air you goin’?” he asked, eagerly. “Hit’s closer to our house. I ain’t seen you since school broke up.”

“I reckon so,” the girl answered him. And then to relieve the situation she offered him cakes. At that he remembered some May-apples in his pocket and produced them with the awkwardness of big-boyhood. Each was still child enough to enjoy the tasteless fruit of the mandrake simply because it was wild; and to him, moreover, it had all the exaggerated value of a boy’s trove. Easter shared her cakes, and theirs was a feast of Arcady. So, too, might the Arcadian shepherds have piped among their flocks; for he tried his whistle again, and she must needs have it in her hands to blow upon it also.

Directly she glanced up and her face brightened. “There’s a hominybird,” she whispered ever so softly. Following her gaze, he, too, saw the tiny creature, swift and brilliant, a flying dagger, more like an insect than a bird. They turned to smile at each other, and as quickly turned away. It poised over flower after flower with a hum as of some heavy double-winged beetle; and ere it could be drunk with sweets a new sound possessed the stillness.

The morning had been vividly many-colored with bird notes. The thrush had waked first, his passionless strain cool as the very voice of dawn; the rest had all carolled of nests and mating, of their lives that were hidden overhead in that trembling world of semi-lucent leaves: keen struggle of life with hunger, brooding tenderness of care for the young, wooing, and quarrelling and fighting, the thousand tiny tragedies and comedies unperceived by human eyes. But now it was a mocker who set the dim, deep-lit shadow a-ripple with the pulsing of his own great little heart, in such wild song as could only come from the wild soul of a winged life—a song of world-old passion, of gladness and youth primordial. Oh, troubadour, what magic is in your wooing? Is it the vast and deep desire of Earth for the returning Sungod—her joy in the year’s unutterable glad release, her yearning to the most ancient of Lovers ever young? . . .

Allison drew himself nearer to the girl, and laid his hand over hers. The mating instinct awakens early in the young people of the mountains—cruelly early; we cannot tell why—as a sweet pain that overtakes the exquisite shyness of childhood unawares. She neither looked toward him nor shrank away. Slowly her hand turned until its moist, warm palm met the boy’s; and before he knew it he had kissed her—anywhere, any way.

A kiss is a mystery and a miracle. Easter sprang up, dazed and thrilled, regardless now of her bare feet—conscious only of a choking in her throat and an impulse to burst into the tearless sobbing of excitement. Allison, frightened perhaps even more than she, stood half turned from her, flushed and tingling from head to foot.

At last he found his tongue. “I won’t do that no more! I just don’t know what made me. . . . Easter, won’t you forget hit?”

It was all he could say.

She barely glanced at him. “I won’t tell hit,” she murmured, and, snatching up her shoes and stockings, fled away, and left him standing so, rebuked, condemned.

Once alone, she flung herself on the ground and hid her face even from herself. This it was, then, to kiss a boy? “Oh dear, why is it like this?” she wept, and crept closer to the ground.

But she had not promised to forget.

When Easter Vanderwelt went to “stay with” her married sister, she planned to come home in time to enter school when it should open, the first Monday in August. There was the half-formulated hope of seeing Allison somewhere, sometime during the term, even if he did consider himself too old to attend. So she stacked her six or eight books in the loft room over the kitchen, with an admonition to her brothers not to disturb them in her absence. She had always kept them neat, and the boys should have them when she had learned them through.

But Cordy’s baby was a fretting, puny thing; Easter finally consented to forego the summer school and stay on till frost, when, it was hoped, the little ones would improve; and the round of toil soon drove out every other thought. Or did it? Four-year-old Phronie and Sonny-buck, his father’s namesake, scarcely out from underfoot, the ailing baby to be tended, preparing cow’s milk, washing bottles, wrapping a quill in soft, clean rags to fit the tiny mouth—looking after these was the task of a wife and mother; Easter could hardly devote all day and every day to them without figuring to herself a future of such, shared with—whom?

The children fell ill and needed to be nursed. There were the walls to tighten against winter with pasted layers of old newspapers. Hog-killing time brought its extra burdens. Cordy, a fierily energetic housewife, would set up a pair of newly pieced spreads and get two needed quilts done against winter. In the midst of it all she got an order for rug-weaving from a city woman, and begged Easter to stay through the cold weather, with the promise of a new dress from this source over and above her wage of seventy-five cents a week.

Easter’s lot was little harder in her sister’s house than at home, and there she had no wages; yet she was glad when at last she could shut the three dollars and seventy-five cents in her hard, rough, red little hand—she had accepted a hen and six chickens in part payment—and set her face once more toward her father’s house. Catching the hen and chickens and putting them into a basket made her late in starting. The sun was high when she turned out of the shortcut through the woods into the big road, and she found herself already tired. If a wagon would come along now, with room for herself and her small belongings—and, sure enough, before she had walked “three sights and a horn-blow” along the road, a wagon did. Who but Allison on the seat, and all by himself! She felt rather shy, this being the first time they had met alone since the morning he kissed her, under the swamp honeysuckles: she wished he had been any one else, but when he greeted her with, “Want ’o ride?” she clambered in over the wheel.

He stowed the basket under the seat. “What ye got thar?” he inquired, for the sake of conversation.

“Hit’s a old hen that stoled her nest and come off with these few chickens,” she answered. “What y’ been a-haulin’?”

“Rails to fence my clearin’,” he told her with pride. He had recently worked out the purchase of a piece of land. “Hit’s got a rich little swag on one ind, and a good rise on the other, in case I sh’d ever want to build. Hit fronts half a acre on the big road, too,” he added, shyly, looking from the corners of his eyes at the girl beside him.

Talking thus, as gravely as two middle-aged people, they rode across Caney Creek and into the ridges. “Gid up,” he gave the command to the team from time to time; but there was no haste in the mules; their long ears flapped as they plodded, and the wheels slid on through the dust as though muffled in velvet. He began to tell her of his hopes and plans, tentatively, without once looking at her.

“If I’m so fortunate—maybe next winter . . . I’ve been spoken to about a position in a hardware store in town, and . . .” He did not finish that sentence, but presently went on: “One man told me last week that he wouldn’t hire a single man—said they was always out nights, and no good in the daytime.”

Now Easter knew that Allison was never out at night to any ill purpose, and she smiled a bit wisely to herself. His favorite pose was that of the cosmopolitan, the widely experienced man; but that was pure boyishness. There was a rough innocence about him, despite his every-day familiarity with all the crimes that lie between the moonshine still and county court. What of evil there was in him seemed to have grown there as naturally as the acrid sap of certain wild vines or the bitterness of dogwood bark. The freakish lawlessness of even the worst mountaineer seems in some way different from the vice and moral deformity of cities, as new corn whiskey is different from absinthe.

Under her sunbonnet the girl inquired, demurely, “Why ’n’t ye stay here?”

“Oh, I’m jist restless, I reckon . . . I would stay if I had a home here.”

That word “home” laid a finger on their lips for full five minutes. Again he ventured, flicking nervously with his whip at the roadside weeds:

“And Mavity wants me in his new saloon. I seed him when I was in Fairplay last week. The wages is good.”

She spoke now quickly enough. “Don’t go thar, Allison! I don’t want to be—worried—’bout you.”

He turned away to hide a swift change of countenance, slashed hard at the inoffending bushes, and jerked out, in a husky, boyish voice, “What makes ye care?”

She dared not be silent. “Because I know how good you air. Because I don’t want to see—a boy like you go wrong.”

“I ain’t good!” he cried, almost roughly. Then he turned to find her looking at him serenely, silently—not quite smiling. . . .

That was all, but it was almost a betrothal to the two. From this moment she tried to imagine what life with him would be like. The picture she saw clearest was of a low-browed cabin in the dusk; through its doorway, glowing with red firelight, a glimpse of a supper awaiting a man’s return.

Mrs. Vanderwelt was as glad to see her daughter home again as was Easter to rejoin the family, but that did not prevent her levying on Easter’s wages. The dish-pan had gone past all mending, and the water-bucket had sprung such a leak that it was no longer fit for use except about the stable. The lantern globe was broken. So Easter reserved for herself only the price of eight yards of gingham.

“Ye’re jist in time for the dance over to Swaford’s,” announced her younger sister, Ellender, when, after the supper dishes were washed, they sat down to tack carpet rags. “They’re goin’ to give one a-Sata’day night.”

“You ’uns a-goin’?” asked Easter. Of course the boys would be there, and all the youngsters of the countryside—Allison, too. There are never enough girls to go round in a frolic in the mountains.

It transpired, however, that Ellender had no dress—at least, none that could appear beside Easter’s contemplated purchase. So Easter was forced to consider the means of providing eight yards for her sister as well as for herself.

This was on Monday. The sisters walked two miles to the store next day, and chose the double quantity of cheaper goods together. It was white with a small pink figure printed at intervals, coarse and loosely woven as a flour-sack. They stitched all day Wednesday, and finished the frocks Thursday morning. But on Thursday evening they received a letter recalling Easter to her sister’s house.

Easter’s trembling hands dropped in her lap.

“Cain’t you go this time, Ellender?” she pleaded.

“Maw says I ain’t old enough to do what Cordy needs. She says you ain’t—sca’cely,” the younger sister protested.

“You-all act like you wanted to git shut o’ me,” Easter almost wept. “Cordy can wait three days. I’m obliged to go to this dance.”

But she knew it was not so. Only in her pain she struck at what was nearest.

Easter’s return found an ominous tremor and strain in her sister’s affairs. At first her girl’s mind groped vainly for the cause. There was the endless toil of spring house-cleaning and truck-patch, of chickens and cows, with the ailing youngest to tend, and Jim Hallet going softly, outcast by his wife’s displeasure, while poor Cordy sat at night mending and freshening all the coarse little garments, scarcely outgrown, putting them in readiness for an expected use.

Oh, it was hard, it was hard on Cordy, thought the girl, pondering this thing of which she had no experience. It was hard; but she had as yet only the outsider’s point of view.

Next week she had a surprise. Allison brought his team on Saturday evening, and asked her, “provided she didn’t mind ridin’ a mule,” to go to the dance with him. It was a long way to Swaford’s Cove, and she would be fearfully tired to-morrow, but she was accustomed to pay dearly for every bit of pleasure, and did not hesitate. So he came again Sunday week to walk with her to the church at Blue Springs, and later took her to the close-of-school entertainment, where she had the pleasure of seeing Ellender speak a piece, clad in the frock that was the counterpart of her own.

In the midst of corn-planting time the baby died. The weak life flickered out one night as it lay across Cordy’s knees. Such was her exhaustion that the physical need of sleep came uppermost, and her grief did not reveal itself till next day.

The little body, cased in a rude pine box, was taken in the wagon to the untended graveyard by the Blue Springs church. Easter and Cordy rode beside Jim on the seat, and three neighbor women were behind in the wagon, sitting in chairs. These, with the Vanderwelt boys, who had helped dig the grave, were the only persons present at the burying. Cordy asked that one of the women should offer a prayer, but they protested that they could not.

“I never prayed out loud—afore folks—in my life,” said one. “I wouldn’t know what to say.”

“If one o’ you’ll hold my baby, I’ll try my best,” faltered the second, after some hesitation. “He’s cuttin’ teeth, and may not let nobody tetch him but me.”

So it proved; and the third, a poor creature of questionable reputation, burst into hysterical sobbing, and answered merely that she did not feel fit.

“I cain’t have it so,” whispered the poor mother, desperately. “I cain’t have my pore baby laid away without no prayer, like hit was some dead animal. Ef nobody else won’t say ary prayer—I will.”

She stood forth, throwing back her sunbonnet, clasped her hands, shut her eyes tight, and gasped. One could see the working in her throat. They waited. Easter stared at the open grave, shallow, because its bottom was solid rock; the impartial sunshine on the crumbling rail fence, and the little group of workaday figures; the rude stones of other graves scattered through the tangle of briers and underbrush. Then Cordy drooped her head, and whispered, with infinite sadness:

“Lord, take care of my pore baby, and give hit a better chance than ever I had.”

“Amen!” Hallet’s deep voice concluded with a dry sob, and the three women whimpered after him, “Amen!”

The earth was hastily shovelled in, and the woman who had accounted herself unfit to pray began crying out loud. Presently Jim led his wife back to the wagon.

She spoke but once during the ride homeward. “An’ I’ve got no idy the next’ll thrive any better,” she said, dry-eyed. Easter, sitting in one of the chairs back in the wagon, held her peace; so this was what life might mean to a woman.

All next week the bereaved mother went about her work muttering and weeping, until both Jim and Easter began to fear for her reason. But presently the work compelled her thoughts away from her loss. She began to take interest in the milk and the chickens; and she noticed Allison and Easter. She told her husband one day that those two would make a good match.

Far from a match, however, was the present state of affairs in that quarter. The mountain people have an overmastering dread of attempting to cope with a delicate situation in words, insomuch that the neighbor who comes to borrow a cup of salt may very likely sit for half an hour on the edge of a chair and then go home without asking for it. And Allison had never kissed her again. But both knew, without having discussed the matter at all, that Allison wished to marry Easter, and that she, although Allison was undoubtedly her man of all men, could not obtain consent of her own mind to agree.

Why?

Cordy awaited her sister’s confidence, and at last it came.

“I’m afeared,” the girl said, and her eyelids crinkled wofully, her mouth twisted so that she was fain to hide her face.

“You don’t need to be afeared,” said Cordy, slowly, staring straight ahead of her. “You’d be better off with him than ye would at home, wouldn’t ye? Life’s mighty hard for women anywhars.”

“Well, I don’ know,” said Easter, doubtfully.

But when, some days after, Allison did formally ask her in so many words, she gave him the same reason for her uncertainty.

“What air you ’feared of?” he demanded at once.

She was silent, terribly embarrassed.

“What is it you’re afeared of—dear? Tell me. Won’t you tell me?” He put his arms around her. She hid her face on his shoulder and began to cry. “You know I’d never mistreat you?”

“Hit ain’t that.”

“What, then?”

“I’m just afeared—afeared of being married.”

He took a little time over this, and met it with the argument, “Would you have any easier time if you didn’t get married?”

She tried to consider this fairly, but there was not an unmarried woman in all her acquaintance to serve as a basis for comparison. Most girls in the mountains marry between the ages of twelve and nineteen. She saw, however, that it was a choice of slavery in her father’s house or slavery in a husband’s.

Then Allison made a speech; his first, and perhaps his last. “Dear, dear girl, I’ll just do the very best I can for you. I cain’t promise no more than that. You know how I’m fixed. I’ve got nothing more to offer you than a cow or two, and a cabin, and what few sticks o’ furniture I’ve put in hit; but that’s more’n a heap o’ people starts with. Hit’s for you to say, and I don’t want to urge ye again’ your will an’ judgment. But I’ve got a chanst now to go North with some men that’ll pay me better wages than I ever have got, and I won’t git back till fall; and I—want—you,” he said, “to be my wife before I go. I want to know, whilst I’m away, that you belong to me. Then, if I was to happen to a accident, on the railroad or anywheres, you’d be just the same as ever, only you’d have the cows, and the team, and my place. Won’t you study about it?”

Easter thought of that for days, in the little time she had for thinking. But she thought, too, of the other side of the picture. Poor child, she had no chance for illusions. Sometimes she felt that she would be walking open-eyed into a trap from which there was no escape save death.

She thought of Cordy at that tiny grave. She dwelt upon her sister’s alienation from her husband. Would she, Easter, ever come to look upon Allison in that way?

Yet the time drew near when Allison must go with those who had employed him. The thing must be decided. There came a heart-shaking day on which, clad in a new dress of cheap lawn made for the occasion, and a pair of slippers, Cordy’s gift, she climbed into his wagon beside the boy, rode away, and came back a wife.

“But I mighty near wisht I hadn’t,” she said, thoughtfully, as she told her sister of the gayety of the impromptu wedding at home.

He wrote every week, some three or four pages—a vast amount of correspondence for a mountaineer. At the end of a month he sent her money, more than she had ever had before. His pride in being able to do this was only equalled by hers as she laid out dollar after dollar, economically, craftily, with the thrift of experience, for household things. He had given no instructions as to how the money was to be used; so she bought her dishes and cooking-pots, a lamp, a fire-shovel, and, by way of extravagance, a play-pretty apiece for Suga’lump and Sonny-buck, and even a tiny cap for Cordy’s baby not yet arrived.

Then, one day, taking the little boy with her, she went to Allison’s cabin to clean house, put her purchases in order, and make the place generally ready for living in on his return.

She chose a fair blue day, not too warm for work. White clouds lolled against the tree-tops and the forest hummed with a pleasant summer sound. She brought water from the spring and scoured the already spotless floor, washed her new dishes and admired their appearance ranged on the built-in shelves across the end of the room, set her lamp on the fireboard, and then spread the bed with new quilts. She stood looking at these, recognizing the various bits of calico: here were scraps of her own and Ellender’s dresses, this block was pieced entirely of the boys’ shirts, this was a piece of mother’s dress, this one had been Cordy’s before she married; others had been contributed by girl friends at school. Presently she went to the door and glanced at the sun. It would soon be time to go back and help Cordy get supper, but she must first rest a little. Seating herself on the doorstep, she began to consider what other things were necessary for keeping house, telling them off on her fingers and trying to calculate their probable cost—pillow-slips, towels, a wash-kettle; perhaps, if Allison thought they could afford it, they would buy a little clock and set it ticking merrily beside the lamp on the fireboard, to be valued more as company than because of any real need of knowing the time of day. Her mother had given her a feather bed and two pillows on the morning of her wedding; Allison would whittle for her a maple bread-bowl, and a spurtle and butter-paddle of cedar; and she herself was raising gourds on Cordy’s back fence, and could make her brooms of sedge-grass.

Thus planning, she felt a strange content steal upon her weariness. It was borne strongly in upon her mind that she was to be supremely happy in this home as well as supremely miserable. She ceased to ask herself whether the one state would be worth the other, realizing for the first time that this was not the question at all, but whether she could afford to refuse the invitation of life, and thus shut herself out from the only development possible to her.

Little Sonny-buck toddled across the floor, a vision of peachblow curves and fairness and dimples. She gathered him into her arms and laid her cheek on his yellow hair, thrilling to feel the delicate ribs and the beat of the baby heart. He began to chirp, “Do ’ome, do ’ome, E’tah,” plucking softly at her collar. Easter bent low, in a heart-break of tenderness, catching him close against her breast. “Oh, if hit was—Allison’s child and mine—”

On reaching home she kindled the supper fire and laid the cloth for the evening meal of bread and fried pork and potatoes; and it was given to her suddenly to understand how much of meaning these every-day services would contain if illuminated by the holy joy of providing for her own.

She fell asleep late that night, smiling into the darkness, but was awakened, it seemed to her, almost at once. Cordy stood before her, lamp in hand, laughing nervously; her temples glistened with tiny drops of sweat, and her eyes were dark and strange.

“It’s time,” said she.

When it was over, and they could, in the gray morn, sit down for a few minutes’ rest before cooking breakfast. Easter saw Jim approach the bed on tiptoe. His wife smiled, and raised the coverlet softly from over a wee elevation. Tears came into the girl’s eyes, and she rose hastily and went to build a fire in the stove.

Beside the wagon road that was the sole avenue of communication between the Blue Spring district and the outer world, Easter sat on the mossy roots of a great beech awaiting her husband’s return. Her sunbonnet lay on the ground at her feet, and she was enjoying herself thoroughly, alone in the rich October woods. She was now almost a woman; her abundant vitality had early ripened into a beauty as superbly borne as that of a red wood-lily. She had walked a long way among the ridges, her weight swinging evenly from one foot to the other at every step with a swift, light roll; she was taking time for once in her life to rejoice with the autumn winds and the riot of color and autumn light. How much of outdoor vigor was incarnate in that muscular body of beech towering beside her! Easter’s eyes ran up from the spreading base to the first sweep of the lower branches, noting the ropelike torsion under the bark. A squirrel, his cheeks too full of nuts even to scold her, peeped excitedly from one hiding-place after another, and finally scampered into safety round the giant bole. Then through a rent in the arras of pendent boughs she saw her man coming.

His grandfathers both had worn the fringed hunting-shirt and the moccasins; and though he himself was clad in the Sunday clothes of a workingman, he moved with the plunge and swing of their hunting gait. Such a keen, clean face as she watched it, uplifted to the light and color and music of the hour! His feet rustled the drifting leaves, and he sang as he came.

It seemed but a moment’s mischief to hide herself behind a tree so as to give him a surprise; but the prompting instinct was older than the tree itself—old as the old race of young lovers.

. . . Suddenly they were face to face. He never knew how he cleared the few remaining steps, nor how he came to be holding both the hands she gave him. They laughed in sheer happiness, and stood looking at each other so, until Easter became embarrassed and stirred uneasily. He drew her hand within his arm as she turned, and, not knowing what else to do, they began to walk together along the leaf-strewn roadside, but stopped as aimlessly as they had started.

To him a woman’s dropped eyes might have meant anything or just nothing at all. He scarcely dared, but drew her to him and bent his head. And somehow their lips met, and his arms were about her, and his cheek—a sandpapery, warm surface that comforted her whole perturbed being with its suggestion of man-strength and promise of husbandly protection—lay against hers.

That kiss was a revelation. To him it brought the ancient sense of mastery, of ownership—the certainty that here was his wife, the mate for whom his twenty years had been period of preparation and waiting. And the tears of half-shamed fright that started under Easter’s lids were dried at their source by the realization that it was her own man who held her, that he loved her utterly, and that her soul trusted in him. She lifted her arms, and her light sleeves fell back from them as she pushed them round his neck.

“Oh, Allison, Allison, Allison, Allison!” she murmured, as she had said his name over to herself so many hundreds of times; only, now she was giving herself to him for good or ill with every repetition.

Before them lay the vision of their probable future—the crude, hard beginning, the suffering and toil that must come; the vision of a life crowned with the triple crown of Love and Labor and Pain. Their young strength rose to meet it with a new dignity of manhood and womanhood. In both their hearts the gladness of love fulfilled was made sublime by the grandeur of responsibility—by the courage required to accept happiness in sure foreknowledge of the suffering of life.

The squirrel ran down the beech and gathered winter provender unheeded; and yellow leaves swirled round them as through the forest came a wind sweet with the year’s keenest wine.