Читать книгу Congo Diary - Ernesto Che Guevara - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

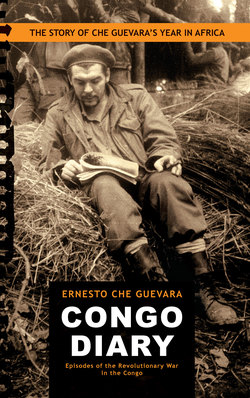

ОглавлениеCHE GUEVARA IN THE CONGO

Gabriel García Márquez

Nothing illustrates the duration and intensity of the Cuban presence in Africa better than the fact that Che Guevara himself, at the prime of his life and the height of his fame, went off to fight in the guerrilla war in the Congo. He left Cuba on April 25, 1965—the very same day on which he submitted his farewell letter to Fidel Castro, giving up his rank of commander and everything else that legally tied him to the government. He traveled out alone on commercial airlines, under cover of an assumed name and an appearance only slightly altered by two expert touches. His executive case contained works of literature and numerous inhalers to relieve his insatiable asthma; he would while away the dull hours in hotel rooms playing endless games of chess with himself. Some time later, he met up in the Congo with 200 Cuban troops who had traveled from Havana in a ship loaded with arms. The precise object of Che’s mission was to train guerrillas for the National Council of the Revolution, which was fighting against Tshombe—that puppet of the former Belgian colonialists and the international mining companies. Patrice Lumumba had been murdered, and although the titular head of the National Council of the Revolution was Gaston Soumialot, the person really in command of operations was Laurent Kabila, based at his Kigoma hideout on the opposite shore of Lake Tanganyika. This situation undoubtedly helped Che Guevara to keep his real identity secret, and for even greater security he did not appear as the principal leader of the mission. That is why he was known by the alias “Tatu,” which is the Swahili word for the number three.

Che Guevara remained in the Congo from April to December 1965, not only training guerrillas but leading them into battle and fighting by their side. His personal links with Fidel Castro, which have been the subject of so much speculation, did not weaken at any moment: the two maintained permanent and friendly contact by means of an excellent communications system.

After Tshombe was overthrown, the Congolese asked the Cubans to withdraw in order to facilitate the conclusion of an armistice. Che left as he had come: without a sound. He took a regular flight to Dar es-Salaam in Tanzania, keeping his head buried in a book of chess problems which he read and re-read throughout the six-hour journey. In the next seat, his Cuban adjutant tried to fend off the political commissar of the Zanzibar army—an old admirer of Che who spoke of him incessantly all the way to Dar es-Salaam, trying to obtain news of him and reiterating his desire to meet him again.

In that fleeting, anonymous passage through Africa, Che Guevara was to sow a seed that no one will destroy. Some of his men went on to Brazzaville, to train guerrilla units for the PAIGC [African Party of the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde] (then led by Amilcar Cabral) and especially for the MPLA. One of these columns later entered Angola in secret and, under the name “Camilo Cienfuegos Column,” joined the struggle against the Portuguese. Another infiltrated into Cabinda and later crossed the river Congo to implant itself in the Dembo region—the birthplace of Agostinho Neto, where the fight against the Portuguese had been going on for five centuries. Thus the recent Cuban aid to Angola [1975–91] resulted not from a passing impulse, but from the consistent policy of the Cuban revolution towards Africa. This time, however, there was a new and dramatic element involved in the delicate Cuban decision. It was no longer a question simply of sending help, but of embarking upon a large-scale regular war, over 10,000 kilometers away, at an incalculable economic and human cost and with many unpredictable political consequences.