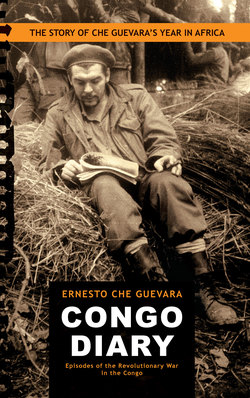

Читать книгу Congo Diary - Ernesto Che Guevara - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE: AN INITIAL WARNING

This is the story of a failure. It descends into anecdotal detail, as one would expect in an account of episodes of a war, but this is modified by observations and a critical spirit as I believe that, were this account to have some merit, it would be to allow certain experiences to be drawn out that might be useful to other revolutionary movements. Victory is a great source of positive experiences, but so is defeat, especially in light of the extraordinary circumstances that surrounded these events: the protagonists and source of information were foreigners who went to risk their lives in an unknown land, where people spoke a different language, and where they were bound only by ties of proletarian internationalism, thereby initiating a new feature in modern wars of liberation.

At the end of the narrative there is an epilogue that poses some questions about the struggle in Africa and, more generally, the national liberation struggle against the neocolonial type of imperialism, the most terrible form in which imperialism presents itself, given the disguises and subtleties that accompany it, and the long experience that the powers that practice it have had in that form of exploitation.

These notes will be published long after they were dictated, and it may be that the author will no longer be able to take responsibility for what is said here. Time will have smoothed many rough edges and, should the publication of these notes be considered to have some importance, the editors may make any corrections they deem necessary (with appropriate footnotes) to clarify events or opinions in light of the time that will have passed.

More accurately, this is the story of a decomposition. When we arrived on Congolese soil, the revolution had stalled; later, events took place that would mean its definitive retrogression, at least at that time and in that immense field of struggle that is the Congo. The aspect that interests us here is not the story of the decomposition of the Congolese revolution. Its causes and key features were too deep for me to have been able to capture them all from my particular vantage point; rather, it is the process of the collapse of our own fighting morale. The experience we initiated should not be ignored and the inauguration of the International Proletarian Army must not be allowed to die at the first failure. It is essential to analyze in depth the problems that arise and find a solution. A good instructor on the battlefield does more for the revolution than the teacher of considerable numbers of raw recruits in peacetime, but the characteristics of this instructor, the catalyst in the training of future revolutionary technical cadres, should be studied carefully.

The idea that guided us was to ensure that men experienced in Cuba’s liberation struggle and the subsequent battles against reaction fought alongside men without experience. We aimed to bring about what we called the “Cubanization” of the Congolese. We will see, however, that the effect was the exact opposite, in that eventually there was a “Congolization” of the Cubans. “Congolization” refers to habits and attitudes toward the revolution that were typical of the Congolese soldiers at that time. This does not reflect a derogatory opinion of the Congolese people, but it does reflect such a view of the soldiers of those days. We will try to explain why those combatants displayed such negative traits in the course of this narrative.

As a general norm, one that I have always followed, nothing but the truth will be told in these pages, or at least in my interpretation of the events, although it may be challenged by other subjective evaluations or corrections, should any errors have crept into my account.

At some points, where it would be indiscreet or inadvisable to tell the truth, some specific references been omitted because there are certain things the enemy should not know. Moreover, what we consider here are issues that may assist friends in the reorganization of the struggle in the Congo (or in the launching of the struggle elsewhere in Africa or other continents that face similar challenges). Among the matters that have been omitted are the ways and means by which we reached Tanzania, our springboard into the setting of this story.1

The names of the Congolese mentioned here are their real ones, but nearly all combatants of the Cuban contingent are referred to by the Swahili names we gave them on their arrival in the Congo. The real names of the compañeros who participated will be included in an appendix, should the editors decide that this would be useful.

Lastly, it is necessary to emphasize that we have highlighted various cases of weakness on the part of individuals or groups, as well as the general demoralization that eventually overcame us, in strict adherence to the truth, recognizing the importance these incidents may have for future liberation movements. But this in no way detracts from the heroic character of the effort. The heroic character of this participation flows from the general position of our government and the Cuban people. Our country, the sole socialist bastion on the doorstep of Yankee imperialism, sends its soldiers to fight and die in a foreign land, on a distant continent, and publicly assumes full responsibility for its actions. In this challenge, in this clear position on the great modern-day issue of waging a relentless struggle against Yankee imperialism, lies the heroic significance of our participation in the struggle of the Congo.

It is there we see the readiness of a people and its leadership not only to defend themselves but to attack, because when it comes to Yankee imperialism, it is not enough to be resolute in defense. It has to be attacked in its bases of support in the colonies and neocolonies that are the foundation of its system of world domination.2

1. Che left Cuba for the Congo on April 1, 1965, after a process of disguising himself in order to assume the identity of Ramón Benítez. He was accompanied by José María Martínez Tamayo and Víctor Dreke. The night before they left, Fidel visited them to say good-bye. They traveled from Cuba to Prague and Cairo and arrived in Tanzania April 5-6. Other members of the column left Cuba in the following weeks, in groups of three or six, and took various different routes, arriving in Tanzania after Che, Martínez Tamayo and Dreke.

2. It is from this perspective that Che analyzes imperialist domination as a world system—how it functions to protect its interests, guarantee exploitation and challenge any attempt at resistance or liberation as well as its various forms of colonialism and neocolonialism. Che’s actions were completely consistent with his ideas. He practiced internationalism in an attempt to coordinate and unify the anti-imperialist struggle.