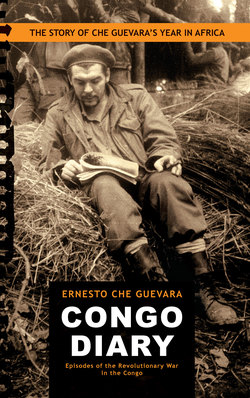

Читать книгу Congo Diary - Ernesto Che Guevara - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFOREWORD

Aleida Guevara March1

I was always told that I would have to start one day, but they did not warn me that it could be so difficult. This book was written by a man whom I have respected and greatly admired ever since I became conscious. Unfortunately he is dead, and therefore unable to express his opinion about what I write, and worst of all for us, nor can he explain what he meant to say and whether today, decades after the events described, he would add an explanatory note. This is why I say that my task is extremely difficult. Che’s diary from the Congo, which remained unpublished [in English] up to now, was preserved in his personal archive, and is now published with stylistic corrections, the incorporation of various observations and the elimination of a number of notes. This represents a great commitment to this history, because various other versions of this manuscript, based on Che’s first transcriptions, have already appeared [in Spanish]. Although he authorized future editors to make whatever changes they thought necessary, we have maintained the complete text that he actually wrote [in 1966] at the end of his mission in the Congo, when he subjected his notes written during the struggle to a deep and critical analysis to make it possible for “experiences to be extracted that might be useful to other revolutionary movements.”

In his preface, titled “An Initial Warning,” Che begins by saying: “This is the story of a failure.” While I don’t agree with this assessment, I can understand his state of mind and how it might be considered a failure. But personally I think it was truly heroic. Anyone who has spent any time in the continent of Africa will certainly understand what I am saying. The degradation it has undergone over the centuries at the hands of so-called European colonizers still leaves its mark on the peoples of Africa: the imposition of a different culture, of other religions, the blocking of the normal development of a civilization, and the exploitation of its natural wealth including the use of its people as slaves, torn from their habitat to be abused and humiliated—all this has deeply marked these human beings. If we consider that it was caused by others who still feel entitled to do such things today, and that in one way or another we allow this to continue, then we can begin to appreciate how people might respond to certain events.

Nevertheless, many people might wonder why Che Guevara participated in this revolutionary process, what motivated him to try and help this movement. It is Che who can best answer this question: “When it comes to Yankee imperialism, it is not enough to be resolute in defense. It has to be attacked in its bases of support in the colonies and neocolonies that are the foundation of its system of world domination.”

Che had always expressed his desire to continue the struggle in other lands. As a doctor by profession and a guerrilla fighter by action, he knew the limitations that life imposes on a human being and the sacrifices demanded by something as hard as guerrilla warfare, so we can understand his desire to transform his dream into reality while he was in the best possible physical condition. We know his deeply rooted sense of responsibility, his political maturity and the commitment he had made to many compañeros who relied on him to continue the struggle.

He had made an earlier trip to Africa where he had the opportunity to meet some of the leaders of the revolutionary movements active at that time, and to familiarize himself with their problems and concerns. He always stayed in touch with Fidel Castro, who, in an unpublished letter dated December 1964, described the measures that were being taken in Cuba at the time.

Che:

I have just met with Sergio [del Valle] who reported in detail on how everything is going. There doesn’t seem to be any difficulty in carrying out the project. Diocles [Torralba] will give you a detailed verbal report.

We will make the final decision on the plan when you return. To be able to choose from the possible alternatives, it is necessary to know the opinion of our friend [Ahmed Ben Bella]. Try to keep us informed by secure means.

It should never be forgotten that the group of Cubans who participated in this mission along with Che shared his conviction: “Our country, the sole socialist bastion on the doorstep of Yankee imperialism, sends its soldiers to fight and die in a foreign land, on a distant continent, and publicly assumes full responsibility for its actions. In this challenge, in this clear position on the great modern-day issue of waging a relentless struggle against Yankee imperialism, lies the heroic significance of our participation in the struggle of the Congo.”

Che and the group he led aimed to strengthen the liberation movement in the Congo, to achieve a united front, to select the best leaders and those prepared to continue the struggle for the final liberation of Africa. He took with him the experience gained in Cuba and placed it at the service of the new revolution.

The harsh realities of the Congo affected Che: its backwardness, the lack of political-ideological development among the people, against which it was necessary to struggle with firmness and determination. There were moments of discouragement and incomprehension, but rising above these adversities, with a prophetic vision, was the enormous confidence and love that he felt for those who decided to create conditions for development and greater dignity for their people.

In Africa, history has been transforming that vision into reality for more than 30 years, as developing education in military matters has become part of revolutionary consciousness. This resulted in such major victories as Cuito Cuanavale [in Angola against the Apartheid forces of South Africa], Ethiopia, Namibia and elsewhere, which have all contributed to the sovereignty and independence of the continent.

The Cuban revolution maintained absolute discretion for as long as possible about Che’s internationalist activity in the Congo, for many months stoically enduring a deluge of slanders. But when the first Central Committee of the Cuban Communist Party was announced [in October 1965], by which time Che was already fully engaged in combat in the Congo, it was decided to make public his farewell letter as it was no longer possible to avoid explaining to the people of Cuba and the world the absence of a man who had been one of the most solid and legendary heroes of the revolution.

In his diary, Che concludes that knowledge of this letter created a rift between himself and the Cuban combatants: “There were some things that we no longer had in common, certain sentiments that I had tacitly or explicitly renounced but which each individual holds most sacred: his family, his surroundings and his homeland.” If this is how he felt, one can imagine how difficult it was for Fidel Castro to get him to return to Cuba. He wrote several times in an attempt to convince Che, and eventually succeeded by means of solid arguments. In June 1966, in an unpublished letter, he wrote to Che:

Dear Ramón:

Events have overtaken my plans for a letter. I read in full the draft of the book on your experiences in the C. [Congo], and I also reread the manual on guerrilla warfare in order to make the best possible analysis of these questions, especially considering the practical importance with regard to plans in the land of Carlitos [Carlos Gardel, ie Argentina]. Although there is no point right now in discussing this with you, I will just say that I found the work on the C. extremely interesting and I think it was really worth the effort you made to leave a written record of everything. […]

About your situation:

I have just read your letter to Bracero [Osmany Cienfuegos] and have spoken extensively with the Doctor [Aleida March, Che’s wife].

In the days when an act of aggression seemed imminent here, I suggested to several compañeros the idea of asking you to return, an idea that turned out to be on everyone’s mind. El Gallego [Manuel Piñeiro2] was given the job of sounding you out. From the letter to Bracero I see that you were thinking exactly the same thing. But right now we can no longer make plans based on that supposition because, as I explained, our impression now is that for the time being nothing is going to happen.

It seems to me, however, that given the delicate and worrying situation in which you find yourself there, that you should consider the usefulness of jumping back here.

I am well aware that you are especially reluctant to consider any option that involves a return to Cuba for the moment, unless it is in the quite exceptional circumstances mentioned above. But analyzed in a sober and objective way, this actually hinders your objectives; worse, it puts them at risk. I find it very hard to accept the idea that this is right, or even that it can be justified from a revolutionary point of view. Your time at the so-called halfway point increases the risks; it makes extraordinarily more difficult the practical tasks that need to be carried out; and far from accelerating the plans, it delays their fulfillment; moreover, it subjects you to a period of unnecessarily anxious, uncertain and impatient waiting.

What is the reason for all this? There can be no question of principle, honor or revolutionary morality involved here that would prevent you from making effective and thorough use of facilities that you can certainly depend on to achieve your goal. No fraud, no deception, no tricking of the people of Cuba or the world is involved in making use of the objective advantages of being able to enter and leave here, to plan and coordinate, to select and train cadres, and to do everything from here that you can achieve only with great difficulty from where you are or somewhere similar. Neither today nor tomorrow, nor at any time in the future, could anyone consider it wrong—nor should you in all conscience. What would really be a grave, unforgivable error is to do things badly when they could be done well; to have a failure when all the possibilities are there for success.

I am not insinuating, not in the least, that you abandon or postpone your plans, nor I am letting myself be carried away by pessimistic considerations due to the difficulties that have arisen. On the contrary, the difficulties can be overcome, and more than ever we can count on having the experience, the conviction and the means to carry out those plans successfully. That is why I think we should make the best and most rational use of the knowledge, the resources and the facilities that we have at our disposal. Since first hatching your now old idea of further action in another setting, have you ever really had enough time to devote yourself entirely to this matter, to conceiving, organizing and executing your plans to the greatest possible extent? […]

It is a huge advantage for you to be able to use what we have here, to have access to houses, isolated farms, mountains, cays and everything essential to organize and personally lead the project, devoting 100 percent of your time to this and drawing on the help of as many others as necessary, with only a very small number of people knowing your whereabouts. You know perfectly well that you can count on these facilities, that there is not the slightest possibility that you will encounter problems or interference for reasons of state or politics. The most difficult thing of all—the official disassociation—has already been done, not without paying a price in the form of slander, intrigues, etc. Is it right that we should not extract the maximum benefit from it? Has any revolutionary ever had such ideal conditions to fulfill their mission, and at a time when that mission acquires great importance for humanity, when the most crucial and decisive struggle for the victory of the peoples is breaking out? […]

Why not do things well if we have every chance to do so? Why don’t we take the minimum time necessary, even while working at the greatest speed? Didn’t Marx, Engels, Lenin, Bolívar and Martí have to wait, sometimes for decades?

Moreover in those times, there were no airplanes or radios or other things that today shrink distances and increase the yield of each hour of a human being’s life. We ourselves had to invest 18 months in Mexico before returning here to Cuba. I am not proposing that you wait decades or even years but only a few months, because I believe that in a matter of months, by working in the way I suggest, you can get underway in conditions incomparably more favorable than those we are trying to achieve at present.

I know you will be 38 on the 14th [of June 1966]. Or maybe you think that a man starts to age from that point.

I hope that these lines will not annoy or upset you. I know that if you analyze what I say seriously, your characteristic honesty will lead you to accept that I am right. But even if you come to a completely different decision, I won’t feel disappointed. I write to you with deep affection and the greatest and most sincere admiration for your brilliant and noble intelligence, your irreproachable conduct and your unyielding character of a whole-hearted revolutionary. And the fact that you might see things differently won’t change these feelings one iota nor affect our collaboration in any way.

That same year Che returned to Cuba.3

On the first anniversary of the victory of the Congolese revolution, I took part in the celebrations and had a chance to talk to some of the compañeros who had fought alongside Che. I also took the opportunity to discuss with them the publication of this book as I was concerned about what they might think of it. Che’s diary is highly critical and quite blunt in the hope that an analysis of the errors made in the Congo would ensure that they were not made again. He makes specific mention of several leaders, including Laurent Kabila, who later became a key leader of that country.4

I was told that Che Guevara is remembered with respect and affection. Most of the Congolese leaders were young at the time but they recalled Che’s simplicity, his modesty and the respect he showed them by placing himself under their command. For this reason, they are aware that his advice has always been useful in the great task of unifying their country and ensuring that for the first time in many years the Congolese people benefit from their country’s wealth.

So in conclusion, we can say that human beings don’t die when their life and example serve as a guide to many others, and those others succeed in continuing that work.

Aleida Guevara March

1. Aleida Guevara March is one of Che Guevara’s daughters. She is a pediatrician and has participated in various Cuban internationalist missions in Africa and Central America.

2. Manuel Piñeiro Losada (Barbarroja or “Red Beard”) after the victory of the revolution held various posts in the Ministry of the Interior, from head of the National Intelligence Directorate to first vice-minister. He was also head of the Americas Department of the Central Committee from 1975 to 1992.

3. Che returned to Cuba in 1966 and immediately began preparations for the guerrilla mission to Bolivia. He left Cuba for Bolivia in November of that year.

4. Laurent Kabila was president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (1997-2001) after overthrowing the dictatorship of Mobuto Sese Seko. He was succeeded by his son Joseph when he was assassinated in 2001.