Читать книгу Wounds: A Memoir of War and Love - Fergal Keane - Страница 10

We Killed All Mankind

ОглавлениеHis manner was that the heads of all those (of what sort so ever they were) which were killed in the day, should be cut off from their bodies, and brought to the place where he encamped at night: and should there be laid on the ground, by each side of the way leading into his own tent: so that none could come into his tent for any cause, but commonly he must pass through a lane of heads … and yet did it bring great terror to the people when they saw the heads of their dead fathers, brothers, children, kinsfolk, and friends lie on the ground before their faces, as they came to speak with the said Colonel.

Thomas Churchyard, A Generall Rehearsall of Warres, 1579

I

This is the story of my grandmother Hannah Purtill, who was a rebel, and her brother Mick and his friend Con Brosnan, and how they took up guns to fight the British Empire and create an independent Ireland. And it is the story of another Irishman, Tobias O’Sullivan, who fought against them because he believed it was his duty to uphold the law of his country. It is the story too of the breaking of bonds and of civil war and of how the wounds of the past shaped the island on which I grew up. Many thousands of people took part in the War of Independence and the Civil War that followed. The story of my own family is one that might differ in some details but is shared by numerous other Irish families. They may have taken different sides but all were changed in some way, and lived in a new state defined by the costs of violence. I have spent much of my life trying to understand why people will kill for a cause and how the act of killing reverberates through the generations. This book is, in part, an attempt to understand my own obsession with war.

It starts in my grandmother’s house in the north Kerry town of Listowel, in the middle of the 1960s.

The house is asleep. My brother and sister are in beds at the other side of the room. My mother is in the room across the landing, next to the door leading up into the attic where cracked uncle Dan once lived among the cobwebs and the crows. The last drinkers have left Alla Sheehy’s next door. His wife Nora Mai is sweeping the floor. She will be muttering, drawing hard on a cigarette, cursing the hour and the work, under the eternal gaze of the stuffed fox on the counter. A Garda will pass soon on his rounds, his ear alert for the murmur of secret drinkers. There are several dozen pubs in Listowel and he will stop to listen at each one. But the only noise is from the dogs barking in the lane between the houses and the sports field.

‘They can sense it,’ my father says. ‘Stay quiet now. Stay quiet and you will hear them.’ He sits at the end of my bed. I can only make out his shape. There is comfort in the tiny orange glow of his cigarette. ‘Listen close,’ he says again, ‘the riders will come soon.’

I am ten years old. My imagination swells in the darkness. My father lives between the story and the reality. He has spent his life faltering between the two. It is his gift and his tragedy. He can make me believe anything.

‘Now! Now! Sit up,’ he says. ‘Do you hear them? They are riding to hell!’

I hear everything that he wills into being: the hooves pounding the midnight earth, the hard music of armour, sword and spur and men’s voices shouting in the late autumn of 1600. Captain Wilmot’s cavalry – armed with the finest muskets Queen Elizabeth’s treasury can procure – stop before the gates of Listowel Castle and by the banks of the River Feale, which flows out of the mountains in neighbouring County Limerick, meandering around Listowel on its way to the Atlantic coast nearby. The garrison refuse to surrender. Above the swift water heads fly. The blood seeps into the salmon pools. Nine Englishmen are killed, but the Irish cannot hold out. They beg for terms but are refused. They must accept the captain’s discretion, which means death in a more or less dreadful form. Wilmot kills them by hanging, a comparative leniency by the bloody standards of the day, according to my father. After the surrender, the legs of eighteen suffocating men kick to the laughter of Wilmot’s men. My father reaches to his throat to mimic the act of hanging.

The priest who is found with the garrison is spared, however. Not for him the breaking of joints with heavy irons, the agonising death that is the fate of another clergymen found near Dingle. The priest has a bargain to offer. He tells Wilmot that the rebel Lord Kerry’s son, ‘but 5 years old … almost naked and besmirched with dirt’,1 has been smuggled out of the castle by an old woman. Who better than the heir to lure the lord into surrender? The old woman and boy are found in a hollow cave and are sent to Dublin with the priest, but their fate is not recorded.

My father pulls ghosts out of history every night. I know that in reality there are no riders as the field behind my grandmother’s house is unmarked when I check it the next morning. ‘Sure that’s your father for the stories,’ Hannah jokes to me when I return. My grandmother has stories too. She is part of more recent wars. If only she would tell me. She fought the English and was threatened with execution. But her stories will remain untold in her own voice.

I am grown and my father is dead when I discover how faithfully he brought the Elizabethan past to life. In the late sixteenth century the conquering English had swept their enemies before them. After capturing Listowel they rode on into Limerick. The president of Munster, Sir George Carew, reported back to London that they had killed ‘all man-kind that were found therein, for a terror to those that should give relief to renegade traitors; thence we came into Arlogh Woods [in County Limerick] where we did the like, not leaving behind us man or beast or corn or cattle’.2 Livestock was slain by the thousand and corn trampled and burned. The Irish peasants were butchered or driven away so that rebels and plotting Spaniards ‘might make no use of them’.3 Ireland was a nest of potential traitors. The possibility of the invasion of England through the ‘back door’, to the west, loomed large in the imaginations of Tudor statesmen and soldiers. Rebellions supported by the pope and the Spanish king reinforced the English terror of the Protestant Reformation being reversed. Such endings, they knew well, only came in tides of blood. Elizabeth’s spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham had been in Paris on 24 August 1572 and lucky to escape the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre of Protestant Huguenots. A delighted Pope Gregory XIII offered a Te Deum and had a special medal struck rejoicing that the Catholic people had triumphed ‘over such a perfidious race’.4

The European wars of religion brought an exterminatory savagery to Ireland. In the Munster of my ancestors unknown thousands were killed in battle, slaughtered out of hand, and starved or killed by disease. The severed heads that lined the path to the tent of Sir Humphrey Gilbert – celebrated soldier–explorer and half-brother of Sir Walter Ralegh – were deemed a necessary price for making Ireland a land ripe for the benefits of English civilisation, lining the pockets of English adventurers, and keeping England safe from the existential threat posed by the kings of Catholic Europe.

II

History began with my father’s stories. It was our history. He had no interest in complex agency, only in the evidence of English perfidy of which there was abundant evidence on our long walks during holidays around the ruined castles of north Kerry. Eamonn was a professional actor, one of the most gifted of his generation, and his voice, the rich, beguiling voice of those stories, has followed me all my days. I walked beside him through the lands of the O’Connors – taken by the English Sandes family, who came with Cromwell in 1649 – to Carrigafoyle Castle with its gaping breach where the Spaniards and Italians, and their Irish allies, were massacred fleeing into the mud of the estuary – and to Teampallin Ban on the edge of Listowel where, under the thick summer grass, lay the bones of the Famine dead. That was the ‘hungry grass’ said my father. Walk on the graves and you would always be hungry.

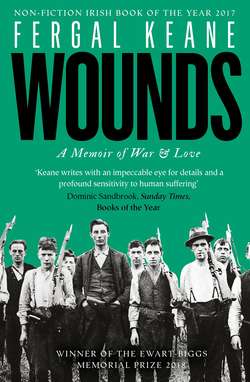

My father the actor (Author’s Private Collection)

In those days Eamonn was a romantic nationalist. My mother Maura was a supporter of the Irish Labour Party and a committed feminist. She disdained nationalist politics. For her the struggle to achieve equal pay and control over her own body were the greater causes. A memory: being sent to Gleeson’s chemist on the corner in Terenure, five minutes’ walk from home, to ask for a package. The brown paper envelope I carried home contained ‘the pill’, something so secret I could not tell a soul. Only later did I learn how the chemist and my mother, in their quiet way, defied the law of the land which forbade women the right to decide if and when they would have children. Maura was raised in a house where no politics was spoken. Her father, Paddy Hassett, had been an IRA man in Cork but he had left the movement when the Civil War started in 1922. Most of his colleagues took up arms against the new Irish state. The only other trace of the revolutionary past I can find in my mother’s life was her friendship with our neighbour, Philippa McPhillips, niece of Kevin O’Higgins, the Free State Justice Minister assassinated by the IRA in 1927 in revenge for his part in the draconian policy of executing Republican prisoners during the Civil War. It was not a political friendship – they were good neighbours – but my mother always spoke of O’Higgins as a man who had been doing what he believed was his best for the country. He was a man we should remember, she said. Still, when my father suggested I should be named after a dead IRA man, my mother acquiesced: Eamonn Keane was a force of nature and not easily refused. Twenty-year-old Fergal O’Hanlon had been killed during a border campaign raid on an RUC barracks on New Year’s Day 1957. The raid was a disaster, and the IRA campaign faded away for lack of support. But O’Hanlon and his comrade Sean South were ritually immortalised by way of ballad:

Oh hark to the tale of young Fergal Ó hAnluain

Who died in Brookboro’ to make Ireland free

For his heart he had pledged to the cause of his country

And he took to the hills like a bold rapparee

And he feared not to walk to the walls of the barracks

A volley of death poured from window to door

Alas for young Fergal, his life blood for freedom

Oh Brookboro’ pavements profused to pour.

(Maitiú Ó’Cinnéide, 1957)

I grew up in Dublin. The city of the mid- to late 1960s was a place of rapid social change. The crammed tenements of James Joyce’s ‘Nighttown’ with its ‘rows of flimsy houses with gaping doors’,5 were mostly gone, their residents dispatched to the suburban council estates and tower blocks as a new Ireland, impatient for prosperity, straining to be free of dullness and small horizons, came into being. Nationalism had a grip on us still. But it had to compete with other temptations. The city of elderly rebels and glowering bishops was also the home to the poet Seamus Heaney, the budding rock musician Phil Lynott, the young lawyer and future president Mary Robinson; the theatres and actors’ green rooms of my father’s professional life were filled with characters who seemed to live bohemian lives untroubled by the orthodoxies of church and state. The country’s most famous gay couple – though it could never be stated openly – ran the Gate Theatre next to the Garden of Remembrance where the heroes of the 1916 rebellion were commemorated. My mother intimated that Micheál McLiammóir and Hilton Edwards were ‘different’ and left it at that. To me they were simply a slightly more mysterious element in the noisy, extravagant, colourful world through which my father moved in the late 1960s. They were part of my cultural milieu, along with English football teams and imported American television series. Still, my father’s attachment to romantic nationalism defined how I saw history. Or I should say how I ‘felt’ history – because thinking played much the lesser part of all that I absorbed in those days.

Dominic Behan visited our home in Dublin. So did the Sinn Féin leader and IRA man Tomás Mac Giolla, and several other Republican luminaries, though by then the IRA was drifting far to the left. My father played the role of the martyred hero Robert Emmet in a benefit concert for Sinn Féin. By that stage the leadership of the organization had drifted to the left, towards doctrinaire Marxism and away from the militarist nationalism of earlier times, but it could still summon up the martyred dead to rally more traditional supporters. My father never hated the English as a people. In drink he would swear damnation on the ghost of Cromwell and weep over the loss of ‘the north’. But he was too imbued with the magic of the English language to be capable of cultural or racial chauvinism. Shakespeare and Laurence Sterne and John Keats had lived in his head since childhood. In one of his many flights of fancy he would even claim kinship with the great Shakespearean English actor Edmund Kean.

Irish history for my father was a series of tragic episodes culminating in the sacred bliss of martyrdom and national redemption. In 1965, the year I was sent to school, Roger Casement’s remains were finally brought home to Ireland. The British had hanged Casement as a traitor in 1916 after he attempted to bring German guns ashore to support the Easter Rising. For nearly fifty years the authorities had refused to allow Casement’s body to be exhumed from his grave in London’s Pentonville Prison, and repatriated. When in March his body was finally brought back to Dublin for burial, my father placed a portrait of Casement on our living-room mantelpiece and told me to be proud of a man who had given up all the honours England could offer in order to fight for Ireland.

On the day of his belated state funeral we were given a half day off from school. The ceremony was broadcast on national television. Our eighty-two-year-old President, Éamon de Valera, defied the advice of his doctors and went to Glasnevin cemetery to tell the nation that Casement’s name ‘would be honoured, not merely here, but by oppressed peoples everywhere’. The following year, Ireland commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the Rising. I remember a ballad that was constantly on the radio. We sang it when we played games of the ‘Rebels and the English’ in the lanes of Terenure in the suburbs of Dublin. I can recall some of the words still:

And we’re all off to Dublin in the green, in the green

Where the helmets glisten in the sun

Where the bay’nets flash and the rifles crash

To the rattle of a Thompson gun …6

The song, by ‘Dermot O’Brien and his Clubmen’, stayed in the charts at number one for six weeks. There was also a slew of commemorative plays, concerts and films for the fiftieth anniversary. Nineteen sixty-six was a big year for my father. He played the hero William Farrell in the television drama When Do You Die, Friend?, which was set during the failed rebellion of 1798. The performance won him the country’s premier acting award. I watched a video of the production for the first time a few years ago. There is a wildness in my father’s eyes. It erupted suddenly in my present. I felt shaken as the old wildness in his nature flashed before me.

I was later sent to school at Terenure College, a private school run by the Carmelite order, where there was conspicuously little in the way of nationalism apart from some small echoes in the singing classes of Leo Maguire, a kind man we nicknamed ‘The Crow’, whose radio programme on RTE featured such staples as ‘The Bold Fenian Men’ and ‘The Wearing of the Green’, harmless stuff in those becalmed days. What I did not know was that during the Civil War the IRA blew up a Free State armoured car outside our school, badly wounding three soldiers and two civilians. None of that bloody past whispered in the trees that lined our rugby pitches.

On Easter Sunday 1966, my father took me into Dublin to watch the anniversary parade of soldiers passing Dublin’s General Post Office. De Valera was there to take the salute, although he stood too far above the heads of the crowd for me to see. Elderly men with medals formed a guard of honour below the reviewing stand. They did not look like heroes; they were just old men in raincoats and hats. Only the dead could be heroes. Like Patrick Pearse, my personal idol in those days. He was handsome and proud and gloriously doomed. My father often recited his poems and speeches.

I read them now and shiver. After nearly three decades reporting conflict I recognise in the words of Pearse a man who spoke of the glory of war only because he had not yet known war: ‘We must accustom ourselves to the thought of arms, to the use of arms. We may make mistakes in the beginning and shoot the wrong people,’ he wrote, ‘but bloodshed is a cleansing and a sanctifying thing, and a nation which regards it as the final horror has lost its manhood. There are many things more horrible than bloodshed; and slavery is one of them.’7

In Ireland they were still shooting the ‘wrong’ people a hundred years after Pearse’s death. The dissident Republican gunmen who swore fealty to his dream, and the criminal gangs who killed with weapons bought from retired revolutionaries, were at it still.

The following year, at Dublin’s Abbey Theatre, my father played the lead role in Dion Boucicault’s The Shaughraun, a melodrama set during the Fenian struggles of the mid-nineteenth century. Early in the play one of the characters speaks of the dispossession of her people by the English and swears vengeance: ‘When these lands were torn from Owen Roe O’Neal in the old times he laid his curse on the spoilers … the land seemed to swallow them up one by one.’8 Eamonn played a roguish poacher who outwits the devilish oppressors. During the play he was shot and seemed to be dead. I had been warned that it would happen but the impact of the gunfire, the sight of him falling, apparently dead, was still traumatic. Afterwards I found him alive backstage. My first experience of the power of the gun ended in smiles and embraces.

I was sent to Scoil Bhríde, an Irish-speaking school in the city which had been founded by Louise Gavan Duffy, a suffragist and veteran of the 1916 Rising, and built on land where Patrick Pearse first established a school in 1908. Michael Collins reputedly hid there during the guerrilla war against British rule in Ireland. We children read aloud the 1916 Proclamation of the Republic and memorised the names of the fallen leaders. ‘We stood twice as tall,’ Bean Uí Cléirigh, my old teacher, told me years later. ‘We felt we could stand with any nation on earth.’9 All I had to do was breathe the air of the place to feel pride in the glorious dead.

I learned that heroism in battle came from a time before the wars with the English. My father read to me the legend of Cù Chulainn, our greatest hero, who loomed out of the mythic past dripping in the gore of his enemies. Pitiless and self-distorting violence runs through the narratives:

The first warp-spasm seized Cú Chulainn, and made him into a monstrous thing, hideous and shapeless, unheard of. His shanks and his joints, every knuckle and angle and organ from head to foot, shook like a tree in the flood or a reed in the stream. His body made a furious twist inside his skin, so that his feet and shins switched to the rear and his heels and calves switched to the front … The hair of his head twisted like the tangle of a red thornbush stuck in a gap; if a royal apple tree with all its kingly fruit were shaken above him, scarce an apple would reach the ground but each would be spiked on a bristle of his hair as it stood up on his scalp with rage.10

Cù Chulainn met his end strapped to a stone, sword in hand, facing the corpses of his enemies piled in walls around him, a raven perched on his shoulder as he faced his last reckoning with the enemies of Ulster. He died gloriously, of course.

My father was of a generation schooled in classical literature. He could read in ancient Greek, in which he came first in Ireland in the Leaving Certificate exams, and as a boy heard his father read Homer’s Iliad aloud, until he was old enough to read it for himself. In the previous century, Irish peasant children had listened to the stories of Achilles and Ulysses from roadside teachers. A German travel writer visiting north Kerry in 1842 discerned a more dutiful reason for the prevalence of Latin speakers among local shepherds, recording that it was ‘generally acquired in reference to the church … it has not been purely for the sake of the aesthetic enjoyment to derived from it or simply for the cultivation of their minds’.11 But such rich cultural reference did influence minds, and it took no vast leap of the imagination to see in our own Cù Chulainn a hero to compete with Achilles.

For Sunday outings my parents would sometimes take us to Tara, seat of the ancient kings, or to nearby Newgrange, where each December the winter solstice illuminated the tombs of our ancient Irish ancestors. I did not need heroes from American films or English comic books. I was a suggestible child, borne along by my father’s passion, my teachers’ certainty and the vividness of our native legends. History and mythology, one blending seamlessly with the other. I was now acutely conscious of my father’s alcoholism. And so I learned the consolation of stories. I escaped the painful present by entering into the heroic past.

In that same year, 1966, events were beginning to unravel in the north that would change all of our lives. The sight of marching nationalists in the Republic unsettled the working-class Protestants of the north, where a Unionist government maintained all power in the hands of the Protestant majority. In the north, the commemoration of the Easter Rising had been a muted affair, but it took little in the way of nationalist self-assertion to prompt a return to the old habit of sectarian murder in Belfast. The Ulster Volunteer Force, named after an earlier Protestant militia, shot and killed two Catholic men in May and June. A Protestant pensioner died when flames from a burning Catholic pub spread to her home. The UVF followed up with a general warning that foreshadowed the murderous years to come. ‘From this day, we declare war against the Irish Republican Army and its splinter groups,’ it announced. ‘Known IRA men will be executed mercilessly and without hesitation. Less extreme measures will be taken against anyone sheltering or helping them, but if they persist in giving them aid, then more extreme methods will be adopted … we solemnly warn the authorities to make no more speeches of appeasement. We are heavily armed Protestants dedicated to this cause.’12

Violence permeated the memory of the Republic. It pulsed through the everyday reality of the north. IRA membership was not an essential qualification for murder at the hands of loyalists. At times any Catholic would do. But the early Troubles did not impinge on my life. The north was far away. In 1968, as the first big civil rights marches were taking place, I went on a trip to Belfast with my mother’s school. I remember the surprise of seeing red pillar boxes, a Union flag flying at the border, the model shop on Queen Street where I bought toy soldiers, the coach stopping on the coast at Newcastle on the way back so that we could hunt under the stones for eels and crabs. It was a brief moment of calm. The following year catastrophe enveloped the six counties. It lasted for decades, long enough for me to grow to adulthood and eventually move the hundred or so miles north to work as a journalist in Belfast.

The Troubles confounded my father. He and my mother had visited Belfast the year before I was born. They’d stayed in a theatrical boarding house on Duncairn Gardens in the north of the city. It was run by Mrs Burns, a kind-hearted Protestant woman who had welcomed generations of actors. But less than a decade later, the district had become a notorious sectarian flashpoint. Near where my parents had once walked freely, a ‘peace’ wall would be erected to keep Protestants and Catholics apart. My father’s romantic nationalism could not survive the onset of the Troubles. He veered between outrage at the British and outrage at the Provisional IRA. When IRA bombs killed civilians he would insist that these new guerrillas had nothing in common with the ‘Old IRA’, in which his mother Hannah and her brother had served. My father believed in the story of the good clean fight. He denied any kinship between the IRA Flying Columns of north Kerry and the men in balaclavas from the Falls Road and Crossmaglen. By then, the rebel in him had vanished.

How could he rhapsodise about the glorious dead of long ago while we watched on the nightly news the burned remains of civilians being gathered up on Bloody Friday? Neither my father nor my mother, or any of my close relatives, understood the north. Until 1969 it had had no practical impact on their lives. They watched from Dublin as curfews were declared and the first British troops arrived. Then came refugee camps in the south for embattled Catholics: 10,000 crossed into the Republic in 1972 – the year of Bloody Sunday, and Bloody Friday;* the year my parents broke up; the year we escaped my father’s headlong descent into alcoholism. The north was burning and blowing up but I was lost in the small room of my own sorrow. Nothing made sense.

The refugees were kept further north. But I remember a group came to the seaside in Ardmore, County Waterford, one weekend in August in the early seventies. They were hard kids from the streets of Belfast and they scared us. An Irish government file from the time gives a good indication of how many southerners felt about the new arrivals: ‘Refugees are not always frightened people who are thankful for the assistance being given them. Some of them can be very demanding and ungrateful, even obstreperous and fractious – as well as, particularly in the case of teenage boys, destructive.’13 Oh yes, we in the Republic had moved a long way from the destructive impulses of war. When crowds clashed with police outside the British embassy in Dublin, a Garda told the Guardian newspaper that ‘We didn’t know what was happening in the North until this lot attacked us.’14

The Provisional IRA became active in the Republic, training and hiding and, very occasionally, shooting at our own security forces. We had army patrols outside the banks, special courts to try IRA suspects and a ‘Heavy Gang’ of policemen who battered confessions out of prisoners. The word ‘subversive’ entered our daily vocabulary. To a middle-class boy like me, Republicans were aggressive young men in pubs selling the Sinn Féin newspaper An Phoblacht, a different and dangerous tribe whom we needed no encouragement to shun. In universities and schools we were now being taught a different history. The story of relentless English awfulness – and let there be no doubt, there had been plenty of it – was replaced by a more nuanced narrative in which the past was complex and sometimes confounding.

I realised by the mid-1970s, as the death toll from shootings and bombings in the north moved towards the thousands, that history was a great deal more than the stories my father had told me. It lay in the untold, in the silences that surrounded the killing in which my own family had been involved, and in the Civil War that had divided family members from old comrades. But for all the new spirit of historical revisionism we were not encouraged to ask the obvious contemporary question: What did the violence of our own past have to do with what we saw nightly on our televisions? What made the violence of my grandmother Hannah’s time right and the violence of the ‘Provos’ wrong? Why was Michael Collins a freedom fighter and Gerry Adams a terrorist?

Interrogating these questions did not suit the agenda of the governments that ruled Ireland during the years of modern IRA violence. They were dealing with a secret army that wanted not only to bomb Ireland to unity but overthrow the southern government in the process. Both our main political parties had been founded by men who put bullets into the heads of informers, policemen and soldiers. By the time I was a teenager the last of them was long gone from public life. Their successors, the children of the Revolution, demanded that violence be kept in the past where it could do no harm. In short, we had had enough of that kind of thing.

In this ambition they were enthusiastically supported by the mass of the population. Whatever it took to keep the Provisional IRA and other Republicans in check down south was, by and large, fine with the Irish people. There might be emotional surges after Bloody Sunday in 1972 or the Republican hunger strikes at the Maze prison in the early 1980s, but the guns of Easter 1916 or the killers in the ‘Tan war’ were not who we were now. The Provisional IRA on the other hand took their cue from the minority within a minority who had declared an All-Ireland Republic with the Easter Rising of 1916, and as long as there was a republic to be fought for they claimed legitimacy for killing in its name. Down south they were hounded and despised, an embarrassing, bearded fringe who occasionally added to the store of public loathing and mistrust by killing a policeman or soldier in the Republic. Any attempt to contrast and compare with the ‘Old IRA’ was officially discouraged for fear of giving comfort to the Provos.

The northern slaughter helped to shut down discussion of the War of Independence and the Civil War – what we now call the Irish Revolution – in families too. I knew only that my paternal grandmother and her brothers, and my maternal grandfather, fought the ‘Black and Tans’, the special paramilitary reserve of the Royal Irish Constabulary. Given all we had been taught as children about the old oppressor it was easy for us, who had no knowledge of blood, to accept that the IRA of the War of Independence would shoot the English to drive them out of Ireland. I was not aware that many of those shot were fellow Irishmen wearing police uniforms. In this reading the Old IRA followed in a direct line from the rebels who faced Elizabeth’s army at Listowel Castle. They killed the invaders.

Nobody spoke to me of the dead Irishmen who fought for the other side; much less of the fratricidal combat that engulfed north Kerry after the British departed in 1922. In my teens I was not inclined to enquire about the long-ago war. It did not interest me much then. I was already looking abroad to the stories of other nations. In Cork City Library, after my family had moved to Cork from Dublin, I devoured biographies of Napoleon and Bismarck. It was the big sweep of history that had me then. The relentless drumbeat of bad news from the north only pushed me to look further away from all of Ireland.

There was another, more painfully personal reason. When my parents separated in 1972 contact with my father’s family, with my grandmother and her people, dropped away. I would see her a couple of times a year at most. Even if I had had the inclination, and she had been willing to speak, there was never the time to ask Hannah the questions. In my mother’s family a similar silence prevailed. Although their father had fought in the War of Independence, my maternal uncles and aunts, with whom I spent most of my time, were largely apolitical. They bemoaned the tragedy of the north but felt helpless; their daily lives and ambitions were circumscribed by an attachment to family and to place, to Cork city where we lived a comfortable middle-class existence far from Belfast and its horrors.

It was only much later that I began to ask the questions that had been lying in wait for years. But by then those who might have given me answers were dead or ailing. Paddy Hassett, my maternal grandfather who fought in Cork, was long gone. He had told his own children nothing of his war service. My aunts and uncles knew only slim details of what had happened in north Kerry during the Revolution. It was only thanks to an interview broadcast in 1980, a year after I entered journalism, that I became aware of the darker history that had engulfed my family in north Kerry.

It took an English journalist, Robert Kee, to produce the first full television history of Ireland. Kee interviewed Black and Tans and British soldiers. He spoke with IRA men who described killing informers and ambushing soldiers. The combatants were old men now, sitting in suburban sitting rooms in their cardigans, calmly retelling the events of nearly sixty years before. It was also the first time I had heard any participant speak of what happened after the British left in 1922, and of how those who rejected the negotiated Anglo-Irish Treaty turned on the new Free State government. Men and women who had fought together against the British became mortal enemies.

I remember a sense of shock because the episode on the Civil War focused on an incident in north Kerry where my family had taken the Free State side. I knew the Free State army had carried out severe reprisals for IRA attacks during the Civil War, but the sort of blood vengeance of ‘Ballyseedy’ evoked the stories my father told me of English massacres. Not on the same scale, of course, but with an unsettling viciousness. In March 1923, in retaliation for the killing of five Free State soldiers in a mine attack, nine IRA prisoners were taken from Tralee barracks to the crossroads at Ballyseedy. One man survived the events that followed.

I listened avidly to the story Stephen Fuller told Robert Kee. He began by recalling the moment the prisoners were taken from jail in Tralee:

He gave us a cigarette and said, ‘That is the last cigarette ye’ll ever smoke. We’re going to blow ye up with a mine.’ We were marched out to a lorry and made to lie flat down and taken out to Ballyseedy … the language, the bad language wasn’t too good. One fellah called us ‘Irish bastards’ … They tied our hands behind our back and left about a foot between the hands and the next fellah. They tied us in a circle around the mine. They tied our legs, and the knees as well, with a rope. And they took off our caps and said we could be praying away as long as we like. The next fellah to me said his prayers, and I said mine too … He said goodbye, and I said goodbye, and the next fellah picked it up and said, ‘Goodbye lads’, and up it went. And I went up with it of course.15

The flesh of the butchered men was found in the trees overlooking the road. The interview with Fuller was for me a moment of revelation. He told his story without emotion or embellishment. I had grown up conscious of the bitterness that followed the Civil War. I knew that our main political parties, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, had grown out of the conflict and that my own family were ‘black’ Fine Gael. Die-hard Collinsites. The side that blew up Fuller and the others at Ballyseedy. Now, in the words of Stephen Fuller, I could begin to glimpse the lived experience of the time rather than surmise the truth from the shreds of political rhetoric.

Irish men killed Irish men in the war of 1922–23. They killed each other in the war that went before it: Irish killing Irish with a fury that shocks to read of decades later. Did it shock them, I wondered, when in the long years afterwards they sat and reflected on the war?

The Fuller interview shook from my memory another of my father’s stories.

‘Watch the ceiling,’ he’d say. ‘Watch and you will see him.’ A man in green uniform would appear and float through the darkness, if I would only wait.

‘He is an English soldier and he was killed on the street outside. Wait and he will come.’

The soldier never came. Another of my father’s yarns.

But years later I find out that Eamonn was telling a version of a truth.

A man had been killed on our street, shot dead close to the Keane family home. He was killed by an IRA unit that included a family friend with whom my grandmother and her brother had soldiered. The war had been sweeping across the hills and fields around my grandparents’ town of Listowel for nearly two years when District Inspector Tobias O’Sullivan, a thirty-eight-year-old married man, an Irish Catholic from County Galway, was shot dead. He was the son of a farmer, the same stock as my grandmother Hannah’s people, and he left a widow and three young children behind. Yet his name was never mentioned. There is no monument to his memory, even though at the time of the killing he was the most powerful man in the locality and it was one of the most talked about events in the area’s recent history.

There are many other uncommemorated deaths and events in the journey that forms this book. It is the story of why my own people were willing to kill, and of how people and nations live with the blood that follows deeds – a story that, in one country or another, I have been trying to tell for the last thirty years but not, until now, in my own place. It has been a journey in search of unwilling ghosts. My grandmother Hannah and her brother Mick left no diaries, letters or tape-recorded interviews. What I have are the few confidences shared with their family, some personal files from the military archives, the accounts of comrades in arms, the official histories and contemporary press reports, and my own memories of those rebels of my blood and of the place that made them.

I have tried to avoid yielding to my own collection of biases; however, a story of family such as this cannot be free of the writer’s personal shading. When writing of the Civil War I am acutely conscious that I come from a family that took the pro-Treaty side and, later, became stalwarts of the political organization founded by Michael Collins and his comrades. But I have tried to describe the vicious cycle of violence in north Kerry as it happened at the time and as it was experienced by the people of my past, doing so, as much as possible, without the benefit of hindsight, and without acquiescing to the justifications offered by either side. This book does not set out to be an academic history of the period, or a forensic account of every military encounter or killing in north Kerry. Others have done this with great skill. This is a memoir written about everyday Irish people who found themselves caught up on both sides in the great national drama that followed the rebellion of 1916. It is not a narrative which all historians of the period are sure to agree with, or indeed which other members of my family will necessarily endorse: every one of them will see the past through their own experiences and memories. The one bias to which I will readily admit is a loathing of war and of all who celebrate the killing of their fellow men and women. The good soldier shows humility in the remembrance of horror.

I have reached an age where I find myself constantly looking back in the direction of my forebears, seeking to understand myself, and my preoccupations, through the stories of their lives. It is only with the coming of peace on the island of Ireland that I have felt able to interrogate my family past with the sense of perspective that the dead deserve. It felt too close while blood was being daily spilled in the north. ‘We return to the lives of those who have gone before us,’ wrote the novelist Colum McCann. ‘Until we come home, eventually, to ourselves.’16 Home is where all my journeys of war begin and end.

* On 30 January 1972, soldiers from the Parachute Regiment opened fire on civil rights marchers in Derry, killing thirteen unarmed people. On 2 February angry crowds marched on the British embassy in Dublin and set it alight. In the events that became known as ‘Bloody Friday’ the IRA carried out multiple bombings in central Belfast on 21 July 1972. The attacks claimed the lives of nine people and injured more than one hundred.