Читать книгу Wounds: A Memoir of War and Love - Fergal Keane - Страница 14

The Ground Beneath Their Feet

ОглавлениеCome all ye loyal heroes wherever you may be

Don’t hire with any master till you know what your work will be

For you must rise up early from the clear daylight till dawn

Or else you won’t be able to plough the Rocks of Bawn …

My shoes they are well worn now, and my socks are getting thin

And my heart is always trembling for fear they might let in

My heart is always trembling from the clear daylight till dawn

I’m afraid I won’t be able to plough the Rocks of Bawn

Anonymous ballad, nineteenth century

I

I walk the land in late October. I am coming down past Ballydonoghue church where my grandmother Hannah was baptised and married, where her father and mother were baptised, married and buried, where her brother Mick hid from the Tans, and where my people still farm and course their greyhounds and cheer Kerry’s Gaelic football team. The wind is in from the Atlantic and growing stronger as the sun sets on Tralee Bay. It is forty years and more since I last walked these lanes. It has been too long. After my parents’ marriage fell apart the trips to Kerry became fewer, and when I did come it was to see my cousins in the town. I keep close to the hedgerow to avoid the gusts. At the end of the hill I turn right towards Lisselton cemetery, which my grandmother would pass on her way to school early in the twentieth century. As the lane curves around towards the graveyard there is a small patch of ground on which lumps of rough-hewn stone are scattered. They are small, each less than the size of a football. There is a sign that reads: ‘Don’t pray for us/ no sins we knew/ But for our parents/ they’ll pray for you.’

This is the Ceallurach, the burial ground of the unbaptised children of the Famine. In Hannah Purtill’s time there was no sign here to mark the land. They didn’t need one. Everybody knew. My grandmother went to school when there were still living survivors of the disaster. Even then, when people sought every patch of ground to work, the little field was left to become overgrown: outside the burial rites of the church but sacred in its own forbidding, heartbreaking way. Nobody would ever use the land.

I am not a stranger to mass graves. In other places I have seen those mounds bulging out of the earth, the shreds of clothing and shards of bone, and humanity reduced to mulch. I have always seen them as an end result. They have been reached after the sermons of hatred, relentless droughts or the advent of some vast pestilence. But at Lisselton the graves of the dead feel like a beginning. They point me in the direction I need to be going. If I am to understand why my people picked up guns and became revolutionaries some of the answer lies here in these Atlantic fields. On this October evening I begin to walk back into my history. Before leaving I pray for the dead.

Remembrance was private, to be kept suppressed in the heart. For with such immense loss, field after field of it across the county, with so many counting the absences, what could they do but face forwards, lean their shoulders into the work of surviving and hold their grief for night-time, after the quenching of lamps.

Hannah Purtill was born about two miles away from the burial place, in 1901. She was one of four children. The family was small by the standard expectations of the Catholic Church. Perhaps my great-grandfather Edmund Purtill decided he would only rear the number of children his small farm could support.

He laboured for the bigger farmers and worked his own few rented acres. Edmund was poor but not dirt poor. There was food on the table each day and his children went to school. I believe the Purtills came originally out of County Clare where the land was some of the worst in the country. I can find records of them in Ballydonoghue as far back as the 1830s. Rocky, marshy fields that gave nothing back without turning men and women old before their time, or driving their children to America. The Purtills were survivors. Famine had been part of their rural existence for centuries. Those who could work took to their feet rather than starve. Sometimes families followed. At some point in the nineteenth century the Purtills migrated across the River Shannon to north Kerry. The migrants were sometimes called spailpíns, meaning labourers. There was a poem we studied at school called ‘An Spailpín Fánach’ (The Wandering Labourer) about the plight of migrant workers in rural Ireland. The man declares he will give up his life of drudgery and serve with the army of Napoleon:

Never again will I go to Cashel,

Selling and trading my health,

Nor to the hiring-fair, sitting by the wall,

A lounger on the roadside,

You’ll not see a hook in my hand for harvesting,

A flail or a short spade,

But the flag of France over my bed,

And the pike for stabbing.

The poem was part of our compulsory school Irish course and I regarded it as a chore. In those days I learned it in Irish, and I had yet to learn a love for the language my father spoke fluently. My Purtill ancestors’ world was too distant and I could not then conceive of a kinship with those hard-pressed men and women of the nineteenth century.

The Purtills owned a couple of cows. The dairy cow had a mortal significance for the small farmer. The Famine had taught them not to depend on a subsistence crop that might fail. My uncle, John B. Keane, said that the ‘the milch cow was goddess … beautiful when she is young … [and] all education, all houses, all food depend on the milk cow, whether we like it or not’.1 The old homestead was still standing when I was a child. By then the Purtills owned some land and a small herd of cattle. I remember whitewash and thatch and the smell of turf burning on the range and a yard spattered with cow dung after the herd had been brought in for milking. I was allowed to milk one of the more docile cows, my grand-uncle Ned urging me on throughout with a cry of ‘Good man boyeen, pull away let you.’

The old cottage was knocked down decades ago and replaced by a modern bungalow. When I last visited, my elderly cousin Willie was in the yard tending to his greyhounds. He lives there alone. As long as Willie can remember the Purtills raced dogs and hunted. There is a shotgun inside his front door for shooting rabbits and foxes, and, I am sure, to deter any intruder who might try and break in. I would call my Purtill relatives ‘hardy’ people. Willie remembers his parents and grandparents, how ‘they worked like slaves’ and were never sick. If you wanted a poem written or a song sung then you asked their in-laws, the Keanes. If you wanted work done or men to fight a war, then go to the Purtills.

The townland of Ballydonoghue occupies around eight hundred acres between the north Kerry hills and the Atlantic. The sea is close by; the Purtills could smell it as they led the cattle to pasture and back. In winter it gave them hard weather and flooded the fields and lanes. Across in the Shannon river direction lies the hill of Cnoc an Óir (the Hill of Gold) where, in my father’s stories, the star-crossed lovers Diarmuid and Gráinne hid from the pursuing Fianna warriors in the world before history. The beautiful Gráinne was to marry the ageing Fionn, leader of the Fianna, but eloped instead with his younger comrade, Diarmuid, the finest of all the Fianna men. Years later, after they are apparently reconciled, Diarmuid was gored by a wild boar while out hunting with Fionn. All Fionn needed to do, my father explained, was to give him a drink of water from his hands to save his life. But he allowed the water to slip through his fingers. The memory of the old betrayal sent Diarmuid to his grave. Memories were long, said my father.

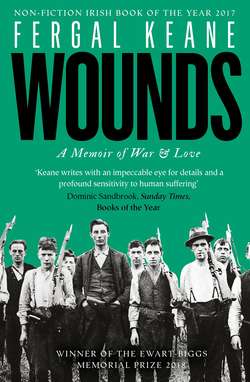

Hannah and Bill, my grandparents (Family Collection)

I revelled in the summer holidays in north Kerry. Legends flickered into life before my eager-to-believe eyes. This world was larger, it was fantastical, and before it my life in the city was reduced to a brittle impermanence. Here a part of my tribe belonged and would always belong. In those days it was not the land-hungry peasantry I saw as my ancestors but, encouraged by my father, a race of warriors and kings and storytellers. My people in Ballydonoghue did not leave behind written accounts of their lives. They passed on stories by word of mouth. They came from a tradition of fabulism. On May eve children were sent to pick up bluebells to place on the hearth to keep away the people of the spirit world who fluttered on the edge of dusk as child-stealers and harbingers of death. It was considered the worst of luck to plough a fairy fort, usually a mound in the middle of a field in which the people of the spirit world lived, waiting their time to reclaim the earth. Fairies controlled the world of the spirits. To cross them was to invite disaster. Foreshadowings of mortality abounded. My grandmother Hannah’s favourite story was about a man who was passing by Lisselton graveyard one night when he heard the sounds of a football match. ‘Will you help out?’ a player asks. ‘We are a man down.’ Like any good Kerryman he joins in and scores several goals. At the end he is approached and told ‘You will be back next week for good’. Within the week the man was dead and buried.

There were legends that hardened into fact, and hard facts that were softened until they became bearable. I found some local schoolchildren’s essays from the 1930s, when Ballydonoghue was little changed from my grandmother’s time. Cottages were still being lit by lamps, short journeys were made by foot, longer ones by donkey and cart; the social life of the parish revolved around Sunday mass and other religious devotions, weekend football games, and conversations at the gates of the creamery. There were dances, but these were often frowned upon and sometimes banned by the priests. A matchmaker by the name of Dan Paddy Andy O’Sullivan brought lonely farmers and prospective wives together. He also ran a dancehall, and in his youth he fought in the guerrilla war against the English alongside my grandmother and my uncles.

‘The name of my home district is Ballydonoghue,’ wrote one of the schoolchildren, eight-year-old Hanna Kelly.2 ‘About fifteen families live there and the population is over a hundred … some of the houses are thatched and some of them are slated. Most of the houses are labourers’ cottages.’ Gaelic was no longer spoken as the people’s tongue. But in everyday speech the translated forms of the old language infused conversation with a lyric intensity. They were heirs to hedge schools and vanished bardic poets and were natural storytellers with a broad extravagant accent that urbane city folk might mock but whose rootedness they quietly envied. The children’s essays noted the departure of young men and women for England and America, and remarked on the handful of Irish speakers who were left in the area. They wrote about the ruins of an old Yeoman’s barracks – a Protestant militia raised during the early 1790s – and about the lost grave of a Dane from Viking times, and of a fort with a pot of gold.

Wide stretches of bog dominated the ground around Ballydonoghue. Willie Purtill used to joke that he graduated from school to the bog at the age of fourteen. Once or twice I footed turf with my cousins. It was backbreaking work for a city boy, and boring for a child who had inherited the Keanes’ capacity for dreaming and being easily distracted. But it was made bearable by the promise of sweets and minerals later. The bog stretched towards the Atlantic and I remember how, if you missed your footing, the mulch below sucked your boots off as you tried to walk out, and how once, after rain at Easter, the bogholes glittered like a thousand broken mirrors in the watery sunlight. At the end of the summer bog cotton flowered: to me it looked like snow or the windblown feathers of swans fallen to earth. It could be picked to be stuffed into pillows and cushions.

Over the years there had been attempts to drain part of the bog and create more arable land and pasture. Between 1840 and 1843 the landlord, Sir Pierce Mahony, a liberal Protestant and ally of Catholic Emancipation, obtained more than £600 in drainage grants from the state. But within a year of the last grant the potato Famine had begun: there were more pressing priorities than drainage and the bog endured. The mid-century traveller Lydia Jane Fisher wrote lyrically of the local landscape, where the green and blue flax flower contrasted ‘with the golden oats, the brown meadows, and the dark green of the potato – all uniting to make the grand mosaic of Nature particularly beautiful at this season. The foxglove, the heath, and the bog myrtle refreshed our senses.’3 But a more realistic appreciation was given by James Fraser who saw that ‘the soil is generally poor, and still more poorly cultivated. The houses of the gentry are few and far between, and the huts of the peasantry are miserable.’4 Those who worked the land, like the Purtills, would not have seen any romance. It was the Keanes, their book-loving future in-laws in the town of Listowel, who would be able to rhapsodise to their hearts’ content about the joys of spring fields.

I recall listening to my father, Eamonn, and a Purtill relative discussing the subject one afternoon in Ballydonoghue. ‘What you have, you hold,’ said my father. ‘Do you hear that boy?’ he said. ‘What you have you hold.’ Land defined the borders of the imagination. To be a man of substance you needed to own the ground underneath you. My father spoke of a relative who was a middleman at cattle fairs but he had no fields of his own. He was famous for his ability to strike bargains between farmers. To show that he was a man of substance he once pinned a five-pound note to his coat. It might seem a comical gesture until you think about the longing that lay behind it. He had no land and never would have. He would always be the dealer in other people’s livestock.

The hunger for land warped men’s spirits. It could drive them to acts of malice. If a cow died on your rented acres you might dump it on your neighbour’s holding to transfer the bad luck. In her eighties one old woman recalled how a row between two hay mowers at the height of the threshing led to one being deliberately poisoned so that he had acute diarrhoea. ‘It was arranged to put something in his tea. In no time he had the runs. There was nothing for it but take off his trousers and work away [for] he was not going to be stopped.’5

My uncle, John B, wrote a play called The Field about a man who kills an interloper in a dispute over the purchase of a field. The field is invested with a sacred quality whose importance can only be understood by those who work its soil. After the murder, a Catholic bishop addresses locals at mass:

This is a parish in which you understand hunger. But there are many hungers. There is hunger for food – a natural hunger. There is the hunger of the flesh – a natural understandable hunger. There is a hunger for home, for love, for children. These things are good – they are good because they are necessary. But there is also the hunger for land. And in this parish, you, and your fathers before you, knew what it was to starve because you did not own your own land – and that has increased; this unappeasable hunger for land … How far are you prepared to go to satisfy this hunger? Are you prepared to go to the point of robbery? Are you prepared to go to the point of murder? Are you prepared to kill for land?6

The answer is yes. Yes, again and again. Why not when, without it, you are scattered and dissolved? Those whose ancestors had starved to death for want of land, who had been dispossessed at the point of a sword, whose oral history had been embedded in the minds of generations, stressing the shame of being a people without land of their own. Land drove men to blood. It is impossible to understand the War of Independence and the Civil War that followed unless you know the story of the land. It is where the hardest of all memories lay, where the grievance and loss accumulated and became ready to flower into violence.

At one point this part of north Kerry had been notorious for faction fighting. In the middle of the nineteenth century feuds between clans and villages would be settled in battles between groups several hundred strong. Deaths and terrible injuries were common. It was said that some of the bad blood could be traced to the plantation of families from neighbouring County Clare during the age of plantation. But this was local talk. Faction fighting was a feature of rural Ireland in this period, often reflecting communal divisions over land usage, employment and social status. One account from the early nineteenth century described how ‘in an instant hundreds of sticks were up – hundreds of heads were broken. In vain the parish priest and his curate rode through the crowd, striking right and left with their whips, in vain a few policemen tried to quell the riot; on it goes until one or other of the factions is beaten and flies’.7 The fighting stick, the shillelagh, was often sharpened to ensure the scalp was cut or weighted with lead to bludgeon the enemy. Most often the matter was settled once blood had been drawn, and the wounded man would retire from the field. One of the most notorious blood feuds, between the Cooleen and Mulvihill factions, was said to be rooted in an ancient dispute over land. In 1834 it came to a head as more than two thousand people took part in a savage battle of Ballyeagh Strand, close to Ballydonoghue. Men and women, including mounted detachments, set about each other with clubs, slash hooks, horseshoes and guns. Twenty people tried to escape in a boat, which overturned in a swift current. As the survivors tried to reach shore they were pelted with stones and driven back into the waters to drown. Not even the local parish priest would give evidence at the subsequent public inquiry. Silence was the law of the land.

The fighting could be exported across the ocean. In the same year as the battle of Ballyeagh, Irish factions fought each other along the banks of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal in Maryland and on the rail lines between Canada and Louisiana – but they fought each other here not for land but for jobs.

The violence of the land was threaded throughout the stories of my childhood. About a mile up the hill from the old Purtill homestead there is a crossroads from where you can see across the plain to Ballyheigue Bay. It was here that An Gabha Beag (‘the Little Blacksmith’), the local leader of the rebel ‘Whiteboys’, was hanged by the English in the early nineteenth century. His name was James Nolan and Hannah used to tell us that he had to be hanged three times because in his forge he had fashioned an iron collar which he placed under his smock to protect his neck. Eventually the redcoats found it and James Nolan was sent to his maker. According to the stories collected by the Ballydonoghue schoolchildren, the landlord responsible for the blacksmith’s death was a Mr Raymond, whose family would haunt the later history of the area. In one version the hanged rebel’s family come to Gabha’s workshop in the dead of night: ‘At MIDNIGHT, so the end of this terrible story goes, seven of the dead men’s nearest relatives came to the forge and there, by the uncanny light of the fire, cursed Raymond’s kith and kin across the anvil. Their curses … did not fall on sticks or stones.’8 The Raymonds were to be damned for all time.

The Whiteboys were a cry of revenge against the exactions of landlords and their agents, against parsons and sometimes priests, against those who turned fields where potatoes grew into grazing for cattle, against the men who fenced and enclosed and who demanded tithes and rents. Named after the white smocks they wore in their night raids, they fought for the rights of tenant farmers and against the system of tithes that maintained the Protestant clergy. The tithes could be exacted in cash or kind and provoked bitter resentment among the Catholic poor. The Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (1836) recorded that in Lisselton parish, which included Ballydonoghue, the Reverend Anthony Stoughton who, along with his brother Thomas, owned much of the land in the district was in receipt of tithes worth approximately £10,000 in today’s money. He also received income from several other parishes in the district. After appeals from the tenants, Stoughton and his brother agreed to reduce their tithe demands, earning gratitude ‘for their kind and considerate mode of dealing with us respecting our Tithes; by which one of our heavy burthens has been considerably lightened – and we sincerely regret that all other Proprietors of Tithes do not follow an example which would in a great measure tend to tranquilize the minds of the people at large’.9 The bigger Catholic landowners, as well as priests who charged for their services at funerals and weddings or condemned the Whiteboys from the pulpit, could also be targets. The raiders maimed and killed cattle, terrorised and sometimes assassinated unpopular landlords and their agents. The founder of Methodism, John Wesley, encountered the Whiteboys whilst visiting County Tipperary and saw how they ‘moved as exactly as regular troops and appeared to be thoroughly disciplined’.10 The violence was episodic but caused widespread terror.

A Whiteboy general, William O’Driscoll, declared: ‘We will continue to oppose our oppressors by the most justifiable means in our power, either until they are glutted with our blood, or until humanity raises her angry voice in the councils of the nation to protect the toiling peasant and lighten his burden.’11 The Whiteboy oath was everything. It gave men a feeling of belonging. And it warned against betrayal. The avenging secret society bound together by oaths became the most powerful force to challenge the established order in early nineteenth-century rural Ireland. ‘I sware I will to the best of my power,’ the oath-taker would declare, to:

Cut Down Kings,

Queens and Princes, Earls, Lords, and all such with

Land Jobbin and Herrisy.12

The English writer Arthur Young, who toured Ireland in the 1770s, wrote about the Whiteboy insurrections and the oppression of the labouring poor. ‘A landlord in Ireland can scarcely invent an order which a servant, labourer or cottier dares to refuse to execute,’ he noted. ‘Disrespect or anything towards sauciness he may punish with his cane or his horsewhip with the most perfect security.’ Young, who had travelled all over the British Isles, was shocked to observe in Ireland long lines of workers’ carts forced into the ditches so that a gentleman’s carriage could pass by. ‘It is manifest,’ Young wrote of the mounting insurgency, ‘that the gentlemen of England never thought of a radical cure from overlooking the real cause of the disease, which in fact lay in themselves, and not in the wretches they doomed to the gallows.’ He then added with unsettling prescience: ‘A better treatment of the poor in Ireland is a very material point to the welfare of the whole British Empire. Events may happen which may convince us fatally of this truth.’13

A landlord in Con Brosnan’s home area of Newtownsandes described the situation in March 1786. ‘We are so pestered with Whiteboys in this country that we can attend to nothing else.’ Landlords were restricted because ‘all law ceases but what the Whiteboys like; not a process is to be served, not a cow drove, nor a man removed from his farm on pain of hanging’. The Whiteboys had erected gallows in Newtownsandes, Listowel and Ballylongford with ‘their entire aim … levelled at the tithes’.14 Traditions of violent resistance were becoming embedded. A decade later a local man, Phil Cunningham, became a leader of the United Irishmen rebellion in County Tipperary. Transported to Australia he died leading a rebellion against the British in 1803.

The fear of a native revolt accompanied by French invasion loomed large in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century politics, as the Whiteboy attacks created panic among local Protestant populations. One informer’s account refers to a ‘meeting of the White Boys at Myre [in Tipperary, where] it was resolved on to burn the houses of the Protestants, and to massacre them in one night, after a landing made by the French, as was expected’.15

Government retribution was harsh. Hundreds of rebels or suspected rebels were transported to Australia. Public hangings were often carried out in the rebels’ home districts. Con Shine, a local carpenter, recalled an execution by soldiers near Listowel in 1808, as told to him by his family: ‘They drove 2 poles in the ground below at the cross and put another pole across they then put him standing in a horse’s car put a rope around his neck then pulled away the car and left him hanging there. He was hanging there all day. The soldiers use to come often and give him a swing for sport and leave him swing away for himself. All the doors were shut that day. You would not see a head out the door.’16

Around Ballydonoghue the Catholic Church condemned the Whiteboy attacks and pledged ‘firm attachment to Our Gracious King and to the Constitution … we will not enter into conspiracy against the laws of our country’.17 A priest in Listowel went further and urged his flock to collect £26 as a reward for anybody giving information on those responsible for the burning houses in the parish. The state archives for the period reflect the efforts made by local priests to discourage support for the Whiteboys. The Listowel magistrate, John Church, records parish meetings across north Kerry and praises the efforts of the clergy while noting claims by the church that the disturbances were caused by poverty and poor weather ‘more than any political motive as maliciously insinuated in some publick Prints’.18 By the late 1820s the campaign for Catholic Emancipation led by Kerryman Daniel O’Connell was on the threshold of success. The church did not want chaos and violence. From the time of the Reformation Catholics had faced a range of restrictions. But in the wake of Cromwellian (1649–53) and then Williamite (1688–91) wars, the repression intensified and a wide range of ‘Penal Laws’ was gradually introduced, targeting Catholics, as well as Presbyterians and other dissenters from the Anglican order. The laws were meant to ensure the ascendancy of Anglicans, with restrictions on Catholic landholding, worship, education, and even a prohibition on Catholics owning a horse worth more than £5. This last imposition was to ensure that strong swift beasts that would be useful for cavalry were kept out of the hands of Catholics. Enforcement varied in different places and with the passage of time some of the most punitive laws were rescinded, but by the 1820s Catholics were still excluded from Parliament and from being judges or senior civil servants. The effect was to make religion synonymous with the power of the minority. Very soon the reverse would obtain. The campaign to achieve Catholic Emancipation galvanised the Irish poor and gave Europe its first great campaign of peaceful mass protest. By 1829 the battle for religious liberty was won and the confessional demography of Irish life had been asserted. The Catholic Church emerged as the most powerful force in Irish life, a role it would not willingly relinquish for the next century and more. But the Church would struggle to control the unrest which arose from the poverty and injustice of the times.

The Whiteboys were succeeded by the ‘Rockites’ in the 1820s, inspired by the millenarian writings of Signor Pastorini, the pseudonym for the English Catholic bishop, Charles Walmesley, who predicted the imminent demise of Protestantism. The north Kerry poet Tomás Ruadh O’Suilleabháin saw the coming deliverance of his people from landlordism and English rule:

It is written in Pastorini

That the Irish will not have to pay rent

And the seas will be speckled with ships

Coming around Cape Clear.19

The local landlords around Ballydonoghue were frightened by the threats of a Protestant apocalypse. In nearby Tarbert one landowner learned of Pastorini’s tract being read ‘among the lower orders of Roman Catholics, who … expect to have the Protestants exterminated out of this kingdom before the year 1825’.20 An agent working for Reverend Stoughton was battered with stones, stabbed to death and then had his ears and nose cut off and placed on public display by his attackers.21 The Rockites, like the Whiteboys before them, were suppressed with customary brutality while O’Connell succeeded in diverting the mass of the rural poor into peaceful campaigning. When the Bill for emancipation was voted into effect on 13 April 1829, the people of Ballydonoghue could look up and cheer the flaming bonfire of triumph on top of Cnoc an Óir. Five years later they gathered for the opening of their new church, a stone building that spoke of permanence and where the Purtills still observe the rites of their faith. The campaign for religious freedom awakened people to the power of their numbers. But the hunger and the structural injustices of rural life ensured that violence would come again. Tithes remained a bane of local life and when they prompted an outbreak of agrarian violence a decade later the Stoughtons were targeted.

In January 1833 the Morning Chronicle recorded that a bailiff working for the Reverend Anthony Stoughton and his brother Colonel Stoughton of Listowel was murdered by being ‘struck on the back of the head with a stone and received about twenty bayonet wounds’.22 On another occasion a horse belonging to the brothers was cut in two. The so called ‘Tithe War’ witnessed a familiar ritual of midnight raids but also the politics of highly organised intimidation, not just aimed at the clergy but against those who agreed to pay their tithes. State retribution was harsh, with instances of troops shooting on protesting crowds. But the conflict marked the beginning of the end of the Church of Ireland as the established church and in 1838 the government acted to transfer responsibility for the upkeep of Anglican clerics to the landlords.*

Poverty is not a necessary precondition for civil strife, but mix it with memories of dispossession, in a system based on the supremacy of a minority, and the emergence of groups such as the Whiteboys, and others in years to come, seems utterly logical. They were men and women with nothing to lose and the raw courage of youth. They did not fight for a nation state, or the republican ideals of Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen. They fought for the ground beneath their feet.

* The final phase in the decline of Church of Ireland power came with the Irish Church Act of 1869 which did away with the payment of tithes and replaced them with a life annuity.