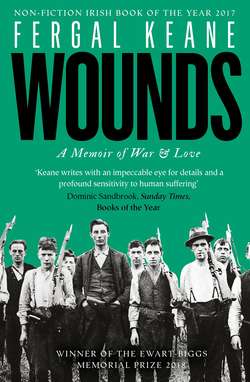

Читать книгу Wounds: A Memoir of War and Love - Fergal Keane - Страница 17

Оглавление4

Revolution

Soldiers are we whose lives are pledged to Ireland …

Peadar Kearney, The Soldier’s Song, 1907

I

To approach a man near his home where his wife and young children are waiting for him, to fire enough bullets into his head and chest to make sure he is dead, and to do this when you have never killed before, and to live with this for fifty years and more and never speak of it: how does a man, a man like you, live with this? Others in Ireland will tell war stories. They will boast of their exploits. Not you. There will be annual parades to attend. You will become part of the national myth of origin that cries out for heroic deeds. But you are remembered as a modest, decent man.

Con Brosnan: hero of the good clean fight against the evil of the Black and Tans. But you know how it really was. It is all there in memory, whenever war comes back: his face down in the space between the cart and the footpath, the blood thickening in the gutter, the children crying. You were brave in the Revolution and a man of peace when it was needed after the Civil War. You were well loved by your own people. For you the act of killing was no lightly taken enterprise. It stays locked inside you for nearly thirty years until the men from the Bureau of Military History came calling.* What you told them was true: you were following orders that came all the way from headquarters in Dublin. But what was the story you told yourself down the years? You were good friends with my uncle Mick Purtill and his sister Hannah. You lived in a neighbouring village, shared the hardship of the Tan war with them, fought on the same side in the Civil War, and after that war you once threatened to shoot a man who had cursed the name of Mick Purtill. ‘The Purtills and Brosnans were fierce close’ was how your son put it.1

A neighbour of yours, the poet Gabriel Fitzmaurice, told me that every day you went to church to pray for the souls of the men you killed. The District Inspector will not be the only killing in which you play a part. It reminded me of something a friend of mine, a Special Forces soldier, a man who killed at close quarters, told me once. He would never let his son join the army, he said. ‘I would never want him to see the things I keep locked up in my head.’

Cornelius – ‘Con’ – Brosnan and Mick Purtill were members of the Irish Volunteers. My grandmother would join the women’s wing, Cumann na mBan, which had been founded in 1914. I believe Hannah was nineteen when she joined; Con Brosnan was the same age when he joined up in 1917.

Con Brosnan, revolutionary and footballing legend (Brosnan Family)

Like the Purtills, Con had grown up on a small farm, supplemented by the income from a public house in Newtownsandes, now called Moyvane – the ‘small, sleepy straggle of a village about seven miles from Listowel in north Kerry, and off the main road’.2 Yet his ancestral background was more complex. On his mother’s side there were business links to the landed gentry of north Kerry. His grandfather, M. J. Nolan, had been a Justice of the Peace and an agent for a protestant landowner. He was shot at during the agrarian disturbances of the late nineteenth century. To get there from Ballydonoghue I drove the long, straight small roads across the plain. I saw the smallness of the killing zone and how the flat terrain with its sparse woodland offered no decisive advantage to guerrillas. I imagine how I would read this land as a war correspondent; the habit is ingrained in me now, a perverse filter through which topography is measured for the cover it provides and the menace it conceals.

There are no steep mountains, plunging valleys; there are no acres of trees or dense scrubland that come up to the roadside for mile after mile. I think of the long drives I have made through ambush zones around the world, my mouth dry and stomach knotted knowing the killers could be as close as the high grass brushing the side of the car. Once in Rwanda I saw them, armed with AK 47s, standing in the middle of the road, surprised by us as we came around the corner of a jungle track. There was a split second when they might have turned on us but they ran into the bush, the element of surprise lost. We turned around and went back, survivors by the grace of chance. So often in armed convoys in guerrilla territory I have strained to see who might be hiding in the passing treelines, or to hear the first shot that would signal an ambush; I have spent fruitless hours calculating whether it was safest to travel in the front, middle or end of a convoy. With enough ambushers and a mine in the road the chances of escape are pretty small, as good friends of mine have found out in Africa, the Balkans and Iraq. Here in north Kerry there was a lot of hiding in plain sight for the men of the IRA. It was in the homes of the people that they found their hiding places, and in barns and dugouts meticulously camouflaged under turf and ricks of hay.

The Brosnan family pub sits in the middle of the town, on a corner beside the road that runs down the gradually levelling land towards Listowel. Con’s son Gerry still lives here and his grandson is a farmer nearby. The flags of the Kerry football team and the Irish Republic hang from stands on the pub’s gable wall. The colonial name of Newtownsandes has been erased. Today the village is called Moyvane – from the Irish for the ‘middle plain’. In his deposition to the military historians, Con Brosnan still referred to it as Newtownsandes. He was born there in 1900 and went to the local national school and then to secondary in Listowel. His schooling ended when he was sixteen, the summer after the Easter Rising.

There was no one reason why Hannah and Mick and Con Brosnan took up arms against the British Empire. Youth was part of it, as was the extraordinary moment in world history when they came of age. They lived in one of those periods when history had slipped its bonds. The impossible became imaginable and then possible and they saw a chance of belonging to something larger than themselves. Events propelled them forward until they became agents of change themselves. It was part politics of the moment and in part the resurrection of long-buried sentiment ignited by the Easter Rising and the events that followed. By 1913 a branch of the Irish Volunteers had been set up in Listowel. The Volunteer movement was a broad coalition that included militant separatists as well as constitutional nationalists devoted to Home Rule. A nationalist private army on such a scale might never have existed but for a dramatic escalation in tensions in Ulster.

By 1910 the dream for which my great-grandfather Edmund Purtill had contributed his shillings seemed to be coming to fruition. The Irish Party held the balance of power in Westminster and Home Rule was the price of their support for the government.* The possibility of nationalist advancement provoked a furious reaction from northern unionists whose response was to threaten civil war. They were encouraged by the leader of the Conservative Party, Andrew Bonar Law. His words are worth remembering, coming as they did from the leader of Her Majesty’s Most Loyal Opposition. In July 1912 he told a rally at Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire that he could ‘imagine no length of resistance to which Ulster can go in which I should not be prepared to support them’. This was no rush of blood to the head. A year later, on 12 July, the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, Bonar Law again threatened treason when he told Ulster Protestants: ‘Whatever steps you may feel compelled to take, whether they are constitutional, or whether in the long run they are unconstitutional, you have the whole Unionist Party, under my leadership, behind you.’3 The Tory leader knew he was adding fuel to the growing fire. Anti-Home Rule agitation had a bloody history. When the first Home Rule bill was introduced in 1886 around fifty people were killed in Belfast, hundreds injured and scores of homes burned. In addition, Bonar Law and the government were well aware that the Ulster Volunteer Force, formed in 1912, were arming and drilling to fight Home Rule.

I doubt that my relatives in Ballydonoghue thought much about the north before then. It was far away on a long train journey or by miles of bad roads. But the rise of the Ulster Volunteers electrified separatists in the south. They watched the British state do nothing to stop the import of weapons by the UVF. If the Ulster Protestants could have a militia to fight Home Rule the Irish nationalists should have an equal right to defend it. The formation of the Irish Volunteers in late 1913 created a second private army on the island. That December, in Listowel, the first meeting of the Irish Volunteers heard Mr J. J. McKenna, a local merchant, urge the locals to follow the example set by the Unionist leader, Edward Carson: ‘He has been going around so far preaching what some called sedition,’ said McKenna. ‘At all events he had been preaching the rights of the people of the North to defend what he called their rights, but whether they were rights or whether they were wrongs, he was urging on them to defend them in the way that God intended.’4 Another speaker said the Irish Volunteers wanted ‘no informers … no cads or cadgers [but] true, manly men’.5 Afterwards men and boys queued to place their right hand on the barrel of a gun and swear allegiance.

From the outset the Irish Volunteers meant different things to different factions. The Home Rulers led by Parnell’s successor John Redmond wanted a force ready to defend the new devolved government when it came into being and hoped the drilling and marching would take some of the steam out of more militant nationalists. But the militants were ahead of him and gradually infiltrated the Irish Volunteers. The Irish Republican Brotherhood – the IRB – sought complete independence rather than Home Rule within the empire.* Separatist ideas in culture and sport had been growing since the end of the previous century.

In the rural areas like north Kerry the appeal to ‘de-Anglicise Ireland’ provoked a strong response. Music, dancing and language lessons sponsored by the Gaelic League became popular.*