Читать книгу Wounds: A Memoir of War and Love - Fergal Keane - Страница 16

My Dark Fathers

ОглавлениеMy Dark Fathers lived the intolerable day

Committed always to the night of wrong,

Stiffened at the hearthstone, the woman lay,

Perished feet nailed to her man’s breastbone.

Grim houses beckoned in the swelling gloom

Of Munster fields where the Atlantic night

Fettered the child within the pit of doom,

And everywhere a going down of light.

Brendan Kennelly, ‘My Dark Fathers’, 19621

I

The Earl was well pleased with his welcome. The gentry had assembled, as had the local clergy, including the formidable Father Jeremiah Mahony, parish priest of St Mary’s, who delivered a vote of thanks to his Protestant counterpart, Reverend Edward Denny, ‘for his dignified conduct on this, and every other occasion, when called on’.2 The occasion was a welcome party for the new Earl of Listowel, William Hare, and the language was indicative of something more than the ritual flattery reserved for visits of the mighty. The priest had reason to welcome the Earl, who had been a supporter of Catholic emancipation and provided land for the new Catholic church on the square directly opposite the Protestant St John’s. His liberalism on religion put him at odds with several powerful fellow landowners in the area. The formal address urged the Earl to make his visits ‘frequent and prolonged’ and sought his ‘protection and tutelage’ for ‘a grateful tenantry’.3 At that moment, seated behind the ivy-clad walls of the Listowel Arms Hotel, among the smiles and handshakes of the men of property, within yards of the Protestant church and its new, taller-spired Catholic counterpart, the Earl might have hoped for a tranquil residence. But beyond the Feale bridge on either side of the road towards Limerick, by the Tarbert road and the road to Ballydonoghue, in every field in north Kerry where potatoes were planted, a catastrophe was taking root.

They were used to hunger. Seven Irish famines of varying extremes had struck since the middle of the eighteenth century. Outside the rapidly industrialising north-east the country was mired in poverty with average income half that of the rest of the United Kingdom. The rural population had grown rapidly, encouraged by the nourishment provided by the widespread cultivation of the potato, and the growing trend to marry young. In the twenty years before the Famine the number of people subsisting in the area increased by nearly two thousand souls.

By the summer of 1839, two years after the new Lord Listowel was welcomed to the town, there were warnings of crisis. At a public meeting in Listowel, the gentry and the clergy (Protestant and Catholic) and prominent townspeople heard reports of the ‘increasing difficulties of the labouring classes of this district from the enormous prices which the commonest provisions have reached; agricultural labour, about the only source of employment, has now already terminated’.4 The meeting noted ominously that the potato crop of the previous harvest had failed. Public works schemes to alleviate the distress of the poor were already under way and 4,000 people each day received rations of oatmeal. The novelist William Makepeace Thackeray passed through Listowel in the same year and saw a town that ‘lies very prettily on a river … [but] it has, on a more intimate acquaintance, by no means the prosperous appearance which a first glance gives it’.5

The writer, at best a condescending witness to Irish travails, went on to record the poverty of the scene, the numerous beggars (their number undoubtedly swollen by the growing hunger in the countryside), the appearance of ‘the usual crowd of idlers round the car: the epileptic idiot holding piteously out his empty tin snuff-box; the brutal idiot, in an old soldier’s coat, proffering his money-box and grinning and clattering the single halfpenny it contained; the old man with no eyelids, calling upon you in the name of the Lord; the woman with a child at her hideous, wrinkled breast; the children without number’.6 The following year the Kerry Evening Post recorded the failure of the potato crop in the north of the county. A landowner near Ballydonoghue noted in his journal: ‘we were concerned to hear many complain of a dry rot appearing more extensively than hitherto … The farmers are very apprehensive of it.’7 In early February the first of the destitute were admitted to the workhouse in Listowel.

The Purtills and their neighbours watched as a vast withering engulfed the fields of north Kerry in the late summer of 1845. The land agent, William Trench, gave a vivid account of his first encounter with the blight:

The leaves of the potatoes on many fields I passed were quite withered, and a strange stench, such as I had never smelt before, but which became a well-known feature in ‘the blight’ for years after, filled the atmosphere adjoining each field of potatoes. The crop of all crops, on which they depended for food, had suddenly melted away, and no adequate arrangements had been made to meet this calamity, the extent of which was so sudden and so terrible that no one had appreciated it in time, and thus thousands perished almost without an effort to save themselves.8

Soon the smell of the rotting crop was thick around Ballydonoghue. It would be followed soon enough by the smell of corpses.

The newspapers of Kerry and Cork provide us with a picture of deepening distress over the Famine years. There was relief, but never enough. Concern by some landlords, but indifference and cruelty from others. In August 1846 the correspondent of the Cork Examiner reported that the potato crop ‘was not partially but totally destroyed in the neighbourhood of Listowel … the common cholera has set in there without a particle of doubt’.9 By autumn desperation had given way to rage. In November a crowd of up to six thousand came to Listowel ‘shouting out “Bread or Blood” and proceeded in the greatest state of excitement to attack the Workhouse … with the intention of forcibly helping themselves to whatever provisions they might find within the building.’10 They were stopped by the intervention of a popular priest.

North Kerry was devastated. The Tralee Evening News of 16 February 1847 described how: ‘Fever and dysentery prevail here to a frightening extent.’ The ‘bloody flux’ reduced its victims to hopelessly defecating shadows who squatted and lurched in roads, lanes, fields, market squares, on the seashore and riverside, reduced by the mayhem of disease, covered in their own waste, uncared for, and, when they died, often left unburied. ‘Men women and children [are] thrown into the graves without a coffin,’ reported the Kerry Examiner, ‘no inquests inquire as to how they came by their death, as hunger has hardened the hearts of the people. Those who survive cannot long remain so – the naked wife and children staring them in the face – their bones penetrating through the skin.’11

A parish historian recorded the deaths of eighty people in 1847, nearly half of whom were buried without coffins.* Kerry had the second-highest rate of recorded deaths from dysentery during the Famine. Starvation and disease would take the lives of around 18,000 people in just a single decade.

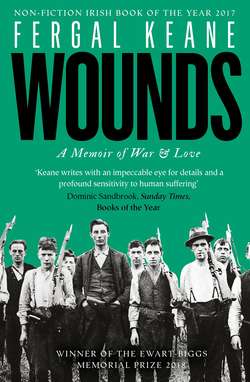

Rural labourer in Famine era (Sean Sexton Collection)

Thousands fled, emigrating to Britain and further afield. Taking ship to escape poverty was an established feature of life in the area and the expanding frontiers of North America offered opportunity. Garret and Mary Galvin from Listowel arrived in Canada with only meagre belongings but within a few years were farming thirty-six acres in Ontario, with twelve cattle, two horses, seventeen pigs and forty sheep. That was in 1826. Two decades later conditions were unrecognisably worse: the government logs of passengers do not even list their names. A few entries picked from the records of the year 1851, hint at the great migration:

18 July: twenty-eight from Listowel make the crossing to Quebec on the ship Jeannie Johnstone.

29 August: sixty-five from Listowel board for Canada on the ship Clio.

26 September: thirteen from Listowel sail on the John Francis …12

Passengers were often selected by their landlords, being of no further economic use on the land, or by the guardians of the workhouses, and sent away to North America with just the price of their fare.

At Quebec the immigrants disembarked at Grosse Isle in the St Lawrence archipelago. Five thousand were buried there, the majority killed by typhus. A priest who went on board the arriving ships left an account of desolation:

Two to three hundred sick might be found in one ship, attacked by typhoid fever and dysentery, most lying on the refuse that had accumulated under them during the voyage; beside the sick and the dying were spread out the corpses that had not yet been buried at sea. On the decks a layer of muck had formed so thick that footprints were noticeable in it. To all this add the bad quality of the water, the scarcity of food and you will conceive but feebly of the sufferings that people endured during the long and hard trip. Sickness and death made terrible inroads on them. On some ships almost a third of the passengers died. The crew members themselves were often in such bad shape that they could hardly man the ship.13

A report from the government in Quebec noted that those ‘sent out by their landlords were chiefly large helpless families, and in many instances widows and their children’ and that they ‘were generally very scantily supplied … The condition of many of the emigrants, I need not inform you, was deplorable.’14 A priest gave the last rites to the dying. ‘I have not taken off my surplice today,’ wrote Father Bernard McGauran, ‘they are dying on the rocks and on the beach, where they have been cast by the sailors who simply could not carry them to the hospitals. We buried 28 yesterday, 28 today, and now (two hours past midnight) there are 30 dead whom we will bury tomorrow. I have not gone to bed for five nights.’15

The Listowel passengers on the ship Clio were told to expect a sum of money from the Listowel Union on arrival. Nothing was sent and they were left ‘entirely without means’. The colonial government moved them on to where they might find work.

In the same period Scots Highlanders were also being shipped out by their landlords. A Colonel Gordon sent his entire tenantry – 1,400 people from the islands of Barra and Uist – to Canada. But to those Irish who were forced into migration, and to those left behind, what mattered was their particular circumstance. Even if they had been aware of the sufferings inflicted on the Scottish and English poor it would not have ameliorated their sense of loss, or the accumulation of grievance that the Famine caused. Nor would it have disposed them to think more highly of the government and the landlords. The wider context is everything until it is nothing at all.

My grandmother Hannah and her brother Mick and their friends were brought up with stories of the Famine as passed on by their grandparents. Moss Keane from Ballygrennan outside Listowel recalled his grandfather’s memories: ‘The families used to get sick and die. The fever was so bad in the end they used to bury the people by throwing their mud houses down on them; then they were buried. The English could relieve them if they wished … Many a person was found dead on the roadside with grass on their mouths.’16 As always the spirit world was invoked in memory of the dead. People told of meeting them along the road.

They were in the ground but walking still.

One story relates how a prosperous landowner came to gloat at a starving old woman. She was so ashamed of her plight that she boiled stones in the pot and pretended they were potatoes. ‘But when the time came, she found flowery bursting spuds in the pot.’17 Another tells of a great fiddler from the locality who was buried in a mass grave and whose music could still be heard on certain nights. I found out that there had indeed been such a man, a famous dancing master who died of exposure in Listowel Workhouse.*

I met a woman walking past Ballydonoghue church one evening who turned out to be a family friend of the Purtills. Nora Mulvihill was born and reared here and came from a line that went back to the nineteenth century. Nora was middle-aged with grown-up children, and most evenings she walked the local roads to keep fit. Drive the roads of rural Ireland any evening and weather and you will see women like her, heads down and arms swinging. She knew the land and its stories.

We drove to Gale cemetery where the dead of the Famine from Ballydonoghue were buried. ‘Do you know about the doctors that were here?’ she asked. I assumed she meant the medics who visited the workhouse during the disease epidemics. But no, Nora had another story. I would leave without knowing how to interpret what I was told. Maybe it was just a story, like so many of the others told over the generations by the old people, a story with some truth maybe or none, or maybe entirely true. But it was a story that lasted. ‘There was a house above in Coolard where there were doctors,’ Nora told me. ‘I don’t know who they were or what they were doing there, whether it was the one family or whatever. But at any rate they lived there through the hunger. At the time there was a lot of dead bodies lying around the place. People were falling on the roads. So the doctors sent their servants out to bring in bodies to them and they had a room upstairs in the house where they did experiments. When they were finished with them a man would come with a cart and take the corpses to the graveyard here.’ The man was known locally as ‘Jack the Dead’.

A local historian, John D. Pierse, found an account of a ‘Dr Raymond [who] used to buy bodies for a couple of shillings from the local people … he’d come at the diseased part of the body and examine it … they used to do that wholesale.’18 The county archives showed that Dr Samuel Raymond was living in this area in 1843, on the eve of the Famine, and was still serving as a magistrate in 1862. It may have been that he was carrying out sample autopsies on behalf of the government. But in the memory of the place he is a ghoulish exploiter to whom the bodies of the dead were mere biological material.

The stories offered the poor a promise that their suffering would be remembered, if not by individual names, then at least the manner of their death, a series of accusing fingers pointing out of the past at the English, the landlords, the big Catholic farmers who had food on their tables every night … at the whole army of their ‘betters’.

The Listowel Workhouse was the repository of the doomed. Those who ended up in this cramped, disease-ridden barracks had lost all hope of survival on the outside. A doctor treating smallpox sufferers found that ‘three or four fever patients are placed in beds that are unusually small’. He witnessed two children die soon after arriving ‘probably being caused by the cold to which such children were exposed to on account of being brought in so long a distance’.19 The doctor found the body of a newborn baby in the latrines. A record for the 22 March 1851 documented the deaths of sixty-six people in the workhouse, of whom forty-nine were under the age of fifteen.

Out of this misery grew an ambitious scheme. A report at the height of the Famine quoted the Listowel Workhouse master as saying ‘the education of the female children appears to be very much neglected … very few could even read very imperfectly. Only one or two make any attempt at writing.’20 The remedy to illiteracy and the prospect of death from starvation or disease was to pack thirty-seven girls off to Australia. They were among 4,000 Irish girls selected to find new lives in the colonies. Most ended up marrying miners or farmers in the outback. In the great departures that followed the Famine, some of my own Purtill relatives took ship for America, settling in Kentucky and New York, and bringing with them a memory of loss to be handed to the coming generations. Their children would learn that as many as half a million people were evicted from their homes during the Famine; that the government failed the starving when it might, through swifter action, have saved hundreds of thousands; they learnt that the poor were damned by the incompetence of ministers and by their rigid ideological beliefs, the conviction that the market was God; that the poor should learn a lesson about the ‘moral hazard’ of their own fecklessness; that too much charity would weaken the paupers’ determination to help themselves – and that all of this was part of God’s plan. It was not genocide in the manner I have known it. Genocide takes a plan for extermination with a defined course set at the outset. But it was a moral crime of staggering proportions.

The Famine changed the world around the Purtills. But they survived. How? Were they tougher than others? I will never know. There is only one narrative of the Famine when I am growing up. This is of English infamy, the clearances and evictions and the workhouse. But it is not the whole story. The story of survival and its psychological costs is not told: how some of the bigger Catholic farmers also evicted tenants, how the vanishing of the labouring class created the room for bigger farms, and how the Famine set in train the destruction of the landlord system. Hunger begets desperation, begets fierce survival strategies, and these beget shame which begets silence.

I find myself going back to Brendan Kennelly’s ‘My Dark Fathers’. I do so because I believe there are parts of history only the poets can convey, the deeper emotional scars that form themselves into ways of seeing things that inhabit later generations. Brendan told me he had written the poem after attending a wedding in north Kerry. A boy was called upon to sing. He had a beautiful voice but was painfully shy. So he turned to face the wall and in this way was able to perform. Kennelly was transfixed. He saw in that moment the shame of survival that had stalked his ancestors and mine.

Skeletoned in darkness, my dark fathers lay

Unknown, and could not understand

The giant grief that trampled night and day,

The awful absence moping through the land.

Upon the headland, the encroaching sea

Left sand that hardened after tides of Spring,

No dancing feet disturbed its symmetry

And those who loved good music ceased to sing.

Since every moment of the clock

Accumulates to form a final name,

Since I am come of Kerry clay and rock,

I celebrate the darkness and the shame

That could compel a man to turn his face

Against the wall, withdrawn from light so strong

And undeceiving, spancelled in a place

Of unapplauding hands and broken song.21

Writing twenty years after the Famine, the lawyer and essayist William O’Connor Morris visited Kerry and found that ‘the memory of the Famine, which disturbed society rudely in this county … has left considerable traces of bitterness’.22 There is an entry in the diary of the landlord Sir John Benn Walsh which recalls a dinner held by the workhouse guardians. It is towards the end of the Famine. Benn Walsh is shocked to find that there are ‘three Catholic priests and a party with them who refused to rise when the Queens health was drunk and a cry was raised of “long live the French Republic” … this little toast shows all the disloyalty in the hearts of those people’.23

The bitterness curdled across the Atlantic into the Irish ghettos of America’s east coast, where hatred of England grew into a revolutionary political force that would return to Ireland, reaching back to the eighteenth century for its defining theme: only total separation from England could cure the ills of Ireland. The lives of the Purtills were transformed in the decades after the Famine but not through armed struggle in a quest for national sovereignty. It was the campaign for land that showed the Purtills and their like what it meant to win.

II

The Landlord and his agent

wrote Davitt from his cell

For selfishness and cruelty

They have no parallel

And the one thing they’re entitled to

these idle thoroughbreds

Is a one-way ticket out of here

third class to Holyhead.

Andy Irvine, Forgotten Hero, 1989

Tenant farmers like Edmund Purtill had few guaranteed rights before the land campaign of the late nineteenth century. Although the rate of evictions had declined considerably, they endured in the collective memory. Joseph O’Connor lived six miles outside Listowel on the lands of Lord Listowel and described his family’s eviction at Christmas time in 1863:

They came on small Christmas Day [6 January, the Feast of the Epiphany] in January 1863, bailiffs, peelers an’ soldiers, an’ had us out on the cold bog before dawn. They burned down the houses for fear we’d go back into them when their backs were turned and took my father and the other grown up men to the Workhouse in Listowel with them. They did that ‘out of charity’ they said because Lady Listowel wouldn’t sleep the night, if the poor creatures were left homeless on the mountain. They left me and my brother Patsy to look after ourselves. We slept out with the hares, a couple o’ nights, eatin’ swedes that had ice in the heart o’ them an’ then we parted. He went east an’ I went west towards Tralee. I must ha’ been a sight, after walkin’ twenty miles on my bare feet an’ an empty belly.24

Cast into destitution by the landlord, Joseph turned to the only means of lawful survival open to him and joined up with the very Crown forces that had turned out his family. In his early teens, O’Connor became a soldier with Her Majesty’s 10th Regiment of Foot. The British Army saved him from starvation.

But these were the last years of the old landlordism. Sixteen years after the O’Connors were driven onto the roads of north Kerry, the rest of rural Ireland was gripped by an agrarian revolution that, for the most part, eschewed the gun in favour of civil defiance. By the time the Land League was formed in 1879 the whole edifice was ready to topple. The Famine had wiped out the rents on which many landlords depended. Rates became impossible to pay. Bankruptcy stalked the landed gentry. ‘An Irish estate is like a sponge,’ wrote one lord, ‘and an Irish landlord is never as rich as when he is rid of his property.’25 Gladstone had already begun the process of strengthening tenants’ rights in 1870. Reform created its own momentum. The Land League would take care of the rest.

Charles Stewart Parnell and Michael Davitt were second only to Michael Collins in my father’s pantheon of greats. It was Parnell, Eamonn said, who gave people back their dignity. Parnell and Davitt were very different men, in temperament and background. Parnell was a Protestant landowner, liberal and nationalist, a brilliant political tactician and leader of the Irish Party at Westminster. His fellow MPs knew him as a man of ‘iron resolution … impenetrable reserve [with] … a volcanic energy and also a ruthless determination’.26 Michael Davitt was the child of an evicted family from County Mayo, brought up in the north of England where he went into the mills as a child labourer, losing his arm at the age of eleven in an industrial accident. Davitt began his political life in the Fenians and in 1870 was sentenced to fifteen years’ hard labour for treason. He was twenty-four years old at the time and endured a harsh regime as a political prisoner. Yet Davitt emerged from jail convinced that violence would never achieve a complete revolution. In this he foreshadowed by a century the experience of the IRA prisoners in the Maze prison. Davitt became an internationalist in prison, seeing the Irish farm labourer as part of the worldwide struggle of the oppressed. Passionate, approachable, he provided the organisational genius of the Land League.

My father occasionally spoke of him, but always the doomed glamour of Parnell, Pearse and Collins shut out the light. Yet Michael Davitt did more than anybody to change the lives of my forebears. I only came to appreciate him in later life – this internationalist and socialist and campaigning foreign correspondent, who made the journey from revolutionary violence to a true people’s politics.

In later life, as a journalist, he revealed the horror of the anti-Semitic pogrom at Kishinev in the tsarist empire in 1903. He arrived in Kishinev ‘a striking figure with a black beard, armless sleeve, and trilby hat’, and set about interviewing the survivors and witnesses.27 His journalism seethed with righteous indignation but was always supported by a meticulous attention to the facts. Davitt came across a house where a young girl had been raped and murdered: ‘The entire place littered with fragments of the furniture, glass, feathers, a scene of the most complete wreckage possible. It was in the inner room (in carpenters shed) where … the young girl of 12 was outraged and literally torn asunder … the shrieks of the girl were heard by the terrified crowd in the shed for a short while and then all was silent.’28 His reporting created an international outcry.

He also went to South Africa as a correspondent during the Boer War, where he felt conflicting emotions as he encountered British prisoners of war: ‘[I felt] a personal sympathy towards them as prisoners; a political feeling that the enemy of Ireland and of nationality was humiliated before me and that I stood in one of the few places in the world in which the power of England was weak, helpless and despised.’29

In Ireland, Davitt had started the Land League campaign with the alluring slogan: ‘The land of Ireland for the people of Ireland’. Huge meetings were held across the country during the late nineteenth century in support of what became known as ‘the Three Fs’: Fixity of Tenure, Fair Rent, and Free Sale. Predictably the agitation brought a return of violent customs in the north Kerry countryside. The targets were not only the old Protestant landlord class. Rural Ireland now had a large body of Catholic bigger, or ‘strong’, farmers, who became targets of the League.

At the height of the land agitation, in the crucial years 1879–85, the colonial government was forced to install a permanent military garrison in Listowel. A bad landlord, a greedy big farmer, might expect retribution in the form of boycott, or a visit from ‘Captain Moonlight’ or the Moonlighters – agrarian raiders who hocked cattle and burned hay barns. Catholics who rented land from others who were evicted or who paid rent in defiance of a boycott were frequent targets. The French writer Paschal Grousset met a man in north Kerry in 1887 whose ears had been mutilated and whose cattle had had their tails docked. The man’s crime was to have accepted work on a boycotted farm. ‘Let a farmer, small or great, decline to enter the organisation,’ wrote Grousset:

or check it by paying rent to the landlord without the reduction agreed to by the tenantry … or commit any other serious offence against the law of the land war, he is boycotted. That is to say he will no longer be able to sell his goods, to buy the necessities of life; to have his horses shod, corn milled, or even exchange a word with a living soul within a radius of fifteen to twenty miles of his house. His servants are tampered with and induced to leave him, his tradespeople shut their doors in his face, his neighbours compelled to cut him … people come and play football in his oat fields, his potatoes are rooted out: his fish or cattle poisoned; his game destroyed.’30

And if he refused to accede to the threats? Grousett put it starkly: ‘Then his business is settled. Someday or other, he will receive a bullet in his arm, if not in his head.’31

Another man, who had shaken the hand of a hated landlord, was forced to wear a black glove on that hand. A seventy-two-year-old writ-server had his left ear sliced off. The land agent S. M. Hussey was forced out of the area after his home was destroyed by dynamite in 1884. There were sixteen people in the house at the time. Miraculously no one was hurt. ‘To show how matters stood,’ he wrote, ‘one of my daughters reminds me that I gave her a very neat revolver as a present, and whenever she came back from school she always slept with it under her pillow.’32 Hussey aroused particular loathing because of a rent rise intended to pay for a £100,000 mansion for one of his landlord clients, and the burning down of several evicted tenants’ houses. The land agent for Lord Listowel, Paul Sweetnam, evicted the O’Connell family at Finuge for non-payment of rent, as a contemporary report described.* ‘When Mr O’Connell came on the scene the eviction was almost completed … He had no place to shelter himself or his family. He came into town and asked the agent for a night’s lodging in the home from which he was evicted. The agent refused.’33

The bigger Catholic farmers watched the violence with alarm. The attackers were nearly always the ‘men of no property’, the rural underclass made up of the sons of small farmers or farm labourers. The land campaigners promised them a stake in the soil they worked. Land would be redistributed. By the beginning of 1880 worsening agricultural prices and poor weather reduced many of the peasantry in the area to destitution. The horror of famine loomed once more. A letter from the organisers of hunger relief in Ballybunion, about five miles from the Purtills, described how the ‘surging crowds of deserving and naked poor who throng the streets every day seeking relief show unmistakably that dire distress prevails in the locality and that unless immediate relief be given and held on for some time there can be no alternative but the blackest Famine … the state of our poor is hourly verging on absolute destitution and the condition of the poor children attending our schools deplorable’.34

Once more a network of secret groups sprang up across the countryside to mete out the people’s justice. Informers were despised. A parallel system of justice with its own courts was set up to adjudicate on land disputes. Ominously, in parts of north Kerry the Royal Irish Constabulary were increasingly identified as the landlord’s enforcers. ‘They have thrown the whole thing on the police,’ a report noted, ‘who for the past six months have acted more in the capacity of herds[men] than policemen and the result is the men are becoming completely worn out, disgusted in their duty and demoralised.’35

The hour of the night raiders was back.

The Moonlighters roamed the country in disguise. They raided to exact retribution and to arm themselves with seized guns. The Catholic farmer John Curtin, a senior local figure in the Land League, was murdered in l885 in south Kerry. One of the attackers was shot during the raid and Curtin’s daughters gave evidence that led to the conviction of some of the Moonlighters. As a consequence, the family was damned. They were booed and jeered when they drove on the local roads. All their servants left. An old man who had herded their cattle for thirty years was too afraid to remain. When they went to mass ‘a derisive cheer was raised by six or eight shameless girls … believing that the police won’t interfere with them’.36 The parish priest ‘never uttered a word in condemnation’. They were again assailed outside the church. The priest, Father Patrick O’Connor, explained that on a previous raid Curtin had surrendered a gun and ‘that if he had given up a gun they would not have hurt a hair on his head’.37 The following week the daughters were accompanied by twenty-five policemen and a representative of the Land League. But the presence of the man from the League made no difference. Stones were thrown. When he tried to address the crowd he was shouted down and afterwards said he owed his life to the police. A group of women ripped out the Curtin family pew and destroyed it in the church grounds. Curtin’s widow could neither sell nor leave. The sale was boycotted. Any prospective buyer was threatened with death. ‘I cannot live here in peace but they won’t let me go,’ she wrote. But the mother of one of the convicted men showed no compassion. ‘As long as I am alive and my children and their children live, we will try to root the Curtins out of the land.’38 The words have an obliterative violence, as if she were speaking of the destruction of weeds. The Nationalist MP John O’Connor sounded a note of hopelessness when he remarked that if the Curtin family was to be protected from the annoyances, to which he regretted they had been subjected, ‘it would have to be by other means than public denunciations of outrages’.39 Not for the last time in Irish history, political condemnations would mean nothing. After eighteen months of hostility the Curtins sold their farm for half of its value and left the area. Nobody, not the police, not the gentry, not the government, could change the minds of their neighbours.

Near to Ballydonoghue, sixty-year-old John Foran was murdered in 1888 for renting the farm of an evicted man. The teenage Bertha Creagh, whose father acted as solicitor for several landlords, saw his killers planning their attack as she went for a walk. ‘I remarked on their evident seriousness to my brother,’ she wrote. Foran was a successful farmer and had gone to Tralee to hire extra help. When on his way home with his labourers and fourteen-year-old son, an assassin appeared out of the woods at a bend in the road and ‘fired from a six-chambered revolver, and lodged bullets in succession in Fohran’s [sic] body … the terrified boy, having waited to lay his dying father on the grass at the roadside, drove on to Listowel’.40 The murdered man was a survivor of the Famine and a contemporary account describes him as ‘being brave even to rashness – that the people of his district had a wholesome dread of himself and his shillelagh’.41 He had also endured four years of harassment – with police protection that had only recently been withdrawn at the time of the murder.

The investigation followed a familiar pattern. There were arrests and court hearings but nobody was convicted. The witnesses kept to the law of silence. In the time of my grandparents, the IRA would draw on those old traditions of silence and communal solidarity.

The Land League was denounced and Parnell and Davitt accused of fomenting violence. The League leaders knew how rural Ireland worked. Violence was not a surprise to them. Davitt condemned the murders but stressed the responsibility of history. ‘The condition and treatment of the poorer tenantry of Ireland have not been, and could not be, humanly speaking, free from the crime which injustice begets everywhere,’ he declared. ‘For that violence which has taken the form of retaliatory chastisement for acknowledged merciless wrong, I make no apology on the part of the victims of Irish landlordism. For me to do so would be to indict Nature for having implanted within us the instinct of self-defence.’42

With tough anti-coercion laws, and a gradual resolution of the land issues, violence abated. The Land War wound down. Parnell led a new campaign for Home Rule before he was destroyed by scandal. Davitt went off to become a journalist and then took a seat in the House of Commons. He dreamed of nationalising the land of Ireland but misunderstood entirely the character of rural Ireland. Only the land a man held for himself offered any security. By 1914, seventy-five per cent of Irish tenants were in a position to buy the land which they rented. They were assisted by British government loans. Labourers were helped by the building of cottages, each on an acre of land. The Purtills bought their own land. In time the sons of the family would move out and buy their own farms. When my cousin Vincent Purtill sold his 400-acre farm and retired he felt agitated. Without the land who was he and where was he? Eventually the stress got the best of him. He went and bought a small farm of twenty-four acres. ‘I need only walk out the door and I am walking on my land. I do it every day,’ he said.

By the early years of the twentieth century, Listowel seemed at peace. Violence was present but contained. It flared occasionally and just as quickly fell away. Tenant farmers used the law to challenge landlords. One case from the Ballydonoghue area in March 1895 shows how dramatically rural life had changed. George Sandes, a descendant of Cromwellian planters, was one of the most powerful landowners in the area. The town of Newtownsandes, about five miles from the Purtills, was named after his family. During the Land War, Sandes was such an unpopular figure that locals attempted to rename the town after one of the Land League leaders. He was a resident magistrate during those years

But in the new rural world forged by Parnell and Davitt, Sandes was no longer free to evict at will. When a farmer went to court to challenge his eviction Sandes lost and was ordered to pay damages.

Constitutional politics were again on the march and Home Rule was promised. My great-grandfather, Edmund Purtill, was listed as donating 1 shilling and sixpence to the cause of the Irish Party at Westminster. Enclosing a cheque for £32 from the parish, the Very Reverend John Molyneaux assured the party treasurer in London that there was not ‘in any parish in the South of Ireland a people more willing and anxious to generously support any movement which has for its object the interests of religion, and the happiness and prosperity of the people’.43 It may have been that Edmund Purtill harboured more radical sympathies and was donating money out of a desire to please the parish priest. But it is more likely that he believed Home Rule within the British Empire was the surest guarantee of stability. The Purtills were still poor but they had a stake in the land. At that point in history, directly on the turn of the century, the majority of Irish Catholics took the same view. The area returned Home Rule MPs at successive elections. The Catholic hierarchy and most of the priests preached cooperation with the government. Nothing in the immediate circumstances of my grandmother’s childhood would have made her or her brothers likely converts to revolution. But there was a desire for change brewing in Ballydonoghue and across Ireland and Europe. The times were about to be disturbed by restless nationalisms that would usher in the end of the age of empire, from the Danube to the River Feale, and make rebels of my forebears.

* The local historian John D. Pierse has published figures showing a fall of 481 in the number of residents in the district in the years 1841–1851 – nearly 22 per cent of the population.

* The writer Catherine E. Foley, an expert on Irish dancing tradition, unearthed the death certificate of ‘Muirin’ in her research on the effects of the Famine on the music and dance culture of the rural poor. She describes him as being fifty-five at the time of his death. ‘Step dancing was seen as a skill to be mastered,’ she writes, ‘a skill that showed individuals had control and mastery over their minds and bodies.’ See Catherine E. Foley, Cultural Memory, Step Dancing, Representation and Performance: An Examination of Tearmann and The Great Famine, in Traditiones (Llubljana 2015).

* Sweetnam came from a Protestant farming background in west Cork. He was an unpopular figure with many in the locality because of his work instigating prosecutions for non-payment of rent for Lord Listowel, and newspapers recorded instances where men who tried to intimidate him ended up in court. In 1899, long after the Land War ended, he appeared in court seeking to evict a Mary Brennan from a caretaker’s house on Lord Listowel’s lands. He would also appear dramatically in the story of District Inspector Tobias O’Sullivan.