Читать книгу Start Small Finish Big - Fred DeLuca - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

chapter one It’s an Entrepreneur’s World

ОглавлениеYou can become part of it by starting small as a microentrepreneur .

Paul Orfalea doesn’t read very well, he has a short attention span, suffers from dyslexia, and he struggled to get through school. But one day, without any business experience and hardly any money, he leased a small space in a garage, leased a copy machine, and launched the business that we know today as Kinko’s. Through trial and error, and by following many of the lessons discussed in this book, Paul was able to turn a profit and eventually expand his business. Today, having started with just $5,000, Kinko’s has opened more than 1,000 business centers worldwide. I’ll tell you more about the development of Kinko’s later in the book. For now, let’s just say that Paul Orfalea started small and he’s finishing big.

Mike Ilitch also started small, and he’s finishing big, bigger than anyone could ever have imagined. In his twenties, the only world Mike knew was baseball. He was an amazing high school athlete, so much so that the Detroit Tigers recruited him during those years. After a stint in the Marine Corps, Mike joined one of the Tigers’ farm teams. He played well for several years, until he broke his ankle, and soon thereafter his baseball career was history. What would he do now to support his young family? He floundered for several years until he opened a small pizza shop. Even then, lacking experience, he experimented with one idea after another. Success wasn’t an overnight phenomenon, but Mike paid attention to the details of his business, he learned one lesson after another, and eventually he opened multiple shops. That was the beginning of the Little Caesar’s pizza chain, now known in nearly every community of the United States. Today, Mike Ilitch not only owns Little Caesar’s, he also owns several major sports franchises in Detroit—including the Tigers—and many other businesses. But I’ll save the rest of Mike’s story, too, for later in the book.

Even though the stories of Paul Orfalea and Mike Ilitch sound incredible, they are typical of the stories you’ll find in this book. They are typical, in fact, of business stories everywhere. I know because I started Subway with $1,000. My story shares many similarities with the stories of Paul, Mike, and the others who you’ll soon meet. We all started with small amounts of money, and my overall message in this book is that you, too, may be able to start small and finish big.

At any given moment in the world millions of people are thinking about starting a business. They are people like you and me, motivated by the desire to be their own boss and to become financially independent. Some want the freedom and the flexibility of self-employment. Others want to make more money, and some are tired of making money for others. Some have lost their jobs, some are about to lose their jobs, and many others are simply tired of their jobs. A business of their own, frightening though it may be, sounds like a logical next step. An exciting next step. If only they can get started.

For most of these millions of people, starting a business will remain merely a dream, locked in the depths of their hearts and minds. It’s something to think about. Something to talk about around the kitchen table, especially with family and friends who share similar dreams. Unfortunately, few take the first bold step to actually start a business. Few can muster the energy and commitment to begin.

Why?

For a variety of reasons, all of which may be valid. They think they don’t have the capital. They think they lack the experience. They think they don’t have the education, or they don’t know how. They don’t feel confident with their plan. They think they need money to make money. And, perhaps more often than not, they never start because a family member or friend told them they couldn’t do it: “You’d be crazy to try...play it safe and stick with your job. So what if you’re miserable. At least you get a paycheck every week. Small businesses never amount to much of anything anyway.”

Does it sound familiar?

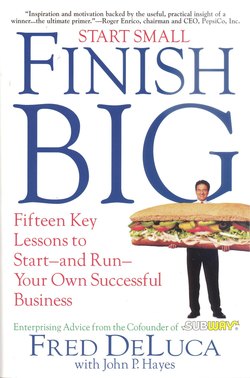

Are you among the millions of people who think about starting a business, but you just never get started? If you are, you’ll be glad you read Start Small, Finish Big. The lessons and messages in this book are especially for you.

Around the world, and especially in the United States, there are plenty of people like Paul Orfalea and Mike Ilitch who start tiny businesses with less than $10,000 (frequently much less). We call these enterprises microbusinesses, the people who start them microentrepreneurs, and the organizations that loan them start-up money microlenders. These are important concepts to me. Microentrepreneurs are frequently overlooked simply because their businesses are tiny, but many of them contribute significantly to the American economy, and to several economies worldwide. Not to mention the fact that many microentrepreneurs generate sizable personal incomes, and they build businesses that can be kept in the family, or sold as valuable assets. I, for one, plan to do all that I can to focus attention on the phenomenon of microenterprise, and you’ll learn more about my interests as you read this book.

Since the beginning of time, people have started businesses with small amounts of money. They begin modestly, without fanfare and often without great expectations. Today, no one knows for sure how many microbusinesses exist or how many are started each year, but the U.S. Small Business Administration reports that first-time entrepreneurs are responsible for 60 percent of business start-ups. Furthermore, the National Federation of Independent Business reports that people under the age of thirty-five launched 1.9 million businesses in 1996, representing nearly half of the businesses started in the U.S. that year. Three quarters of these young entrepreneurs started from scratch, with almost nothing!

Microentrepreneurs come from all walks of life. Male and female. People of color. Able-bodied and people with disabilities. Some have business experience, but most do not. Some may be government dependent, but most are not. Some are young—even preteens—and some are old. Many are retired; they start microbusinesses for something to do, or to supplement their income. Microentrepreneurs are as likely to be high school dropouts as they are college graduates. Formal education is of no significance here. Many of them are employed full-time and start their microenterprises part-time. Frequently they work from home, a basement, a garage, or a truck. Some own multiple enterprises. Some work with partners, especially spouses. But most work alone, at least initially. Microentrepreneurs don’t necessarily register their businesses at first, especially if they work from home. They may or may not file for local or state licenses. Most microentrepreneurs, in fact, don’t know they are microentrepreneurs. And they may not even care. They think of an idea one day, and the next day they’re in business. With the exception of their prospective customers, they don’t really have to tell anyone what they’re doing.

In their smallest form, microbusinesses feed families, rescue victims from welfare rolls, and replace shame with dignity. Some microbusinesses are intended to supplement a full-time income, or to pay college tuition, or to buy necessities, or even luxuries that would otherwise be out of reach. Many of these businesses remain small, others expand into regional or national operations, and some become international entities. According to the U.S. Agency for International Development, which supports its own Microenterprise Initiative, microenterprises often employ a third or more of the labor force in lower-income countries.

There are few prerequisites for microentrepreneurs. Basically, they need an idea, a little bit of money, and most importantly the desire to get started. There’s nothing complicated about what they do. You’re not likely to read about them in the newspapers. They don’t announce the start-up of their businesses on radio and television, or even the Internet. They simply start. And regardless of how many people these microentrepreneurs employ initially, how much money they generate annually, or how many locations they start with, they all have the potential to grow and finish big. As big as they desire. Sometimes bigger than they can imagine. More often than most people know, as microbusinesses mature they create dozens, hundreds, and sometimes thousands of jobs, and they generate millions, sometimes billions, of dollars in annual revenues.

In an age of corporate and social downsizing, and in an era when people are moving back to smaller towns to simplify their lives, the day of the microentrepreneur has arrived. Or perhaps, more accurately, it has returned. It’s a new millennium, and the stage has been set for microentrepreneurs. In the years to come, we can expect to see a proliferation of microenterprises worldwide.

Somewhere right now, perhaps in your own community, there’s a microbusiness that’s headed for stardom in tomorrow’s business press. Perhaps it’s your business, or a business that you’re thinking about beginning. If so, I believe you’ve found an important resource in this book.

Conventional wisdom offers little hope to those who dare to try what so many say can’t be done. But Start Small, Finish Big is a book about hope. For those who dare to take the first step beyond just thinking about starting a small business, this is a book filled with ideas and possibilities. It’s a book that helps overcome the excuses. No matter what your situation may be, Start Small, Finish Big provides a boost for those who seek the confidence, guidance, encouragement, and the will to get started, or to persist, in a business.

If you’re reading this book because you want to start your own business, or expand an existing business, here’s what you’re about to learn.

The Fifteen Key Lessons. Based on my personal experiences as a microentrepreneur, and the experiences of twenty-one other microentrepreneurs whose stories are included in this book, I’ll share with you the Fifteen Key Lessons that will help you start small and finish big.

These lessons are:

1. Start Small. It’s better than never starting at all.

2. Earn a Few Pennies. It’s good practice before you earn those dollars.

3. Begin With an Idea. There’s probably a good one right under your nose.

4. Think Like a Visionary. Always look for the Big Picture.

5. Keep the Faith. Believe in yourself and your business, even when others don’t.

6. Ready, Fire, Aim! If you think too much about it, you may never start.

7. Profit or Perish. Increase sales, decrease costs. Anything less and your business will perish.

8. Be Positive. The School of Hard Knocks will beat you down, but not if you keep a positive attitude.

9. Continuously Improve Your Business. It’s the best way to attract customers, and generate sales and profit.

10. Believe In Your People. Or they may get even with you!

11. Never Run Out of Money. It’s the most important lesson in business.

12. Attract New Customers Every Day. Awareness, Trial, and Usage work every time.

13. Be Persistent: Don’t Give Up. You only fail if you quit.

14. Build a Brand Name! Earn your reputation.

15. Opportunity Waits for No One. Good or bad, breaks are what you make them.

Why are these lessons valuable? Because if you follow them, you are more likely to be successful in the development of your business. These are the lessons I learned while building Subway, and they’re the same lessons that many other microentrepreneurs have learned and applied, too. If you plan to grow your business beyond a one- or two-person enterprise, there will be other lessons to learn, of course. But these Fifteen Key Lessons will help you get started and keep you focused.

Start Small, Finish Big will introduce you to a variety of microentrepreneurs who, like me, began their businesses on financial shoestrings. Their stories illustrate and highlight each of the Fifteen Key Lessons. Instead of relying only on my experiences, or my interpretation of a particular lesson, you will also gain the richly instructional and personal perspectives of these microentrepreneurs. Their stories usually illustrate not one, but several of the Fifteen Key Lessons, and that’s because no one lesson is sufficient to build a successful business. It’s a combination of these lessons, if not all of the lessons, that allows you to start small and finish big.

A few of the microentrepreneurs in the book are still building their businesses. You may find their stories encouraging and uplifting. The challenges they battled and conquered, and the challenges they still struggle to resolve, serve as good examples of what you can expect should you choose to become a microentrepreneur.

Some of the other microentrepreneurs in the book have grown their small enterprises into national and international brand names, but they have not forgotten their humble beginnings, and they gladly share their stories in the hopes of helping you accomplish your dream of business ownership. In several cases, you’ll immediately recognize their company names, although you may not ever have heard of the entrepreneurs who are responsible for the company’s success. These stories, too, should inspire and motivate you as you think about starting a business, or expanding an existing business.

You’ll learn about the value of building a brand from Paul Orfalea. Mike Ilitch demonstrates how a couple of bad breaks can lead to great opportunities. Mary Ellen Sheets, a founder of Two Men & A Truck, shares her ideas about the importance of constantly improving a business. Jim Cavanaugh, who built Jani-King, the world’s largest commercial cleaning company, shows you what can happen when you look for the Big Picture. And a name that’s widely recognized for motivation and inspiration, Zig Ziglar, reveals the down-and-out story of a man who developed a positive attitude and continues to earn his stripes at the School of Hard Knocks.

Then there’s the inventor Tomima Edmark, who wondered one day if she could turn a ponytail inside out. That one creative thought sparked the idea for the TopsyTail, and Tomima has been coming up with ideas ever since. Frank Argenbright literally earned pennies before he earned his first dollar, and today his company, AHL Services, Inc., a contract staffing business, generates a billion dollars in sales annually. Tom Morales wasn’t ready to start his own business, but one day, annoyed with his job, he decided to resign. After fumbling for a while, he started TomKats, a catering business that serves the movie industry. Tom shows us that even if you haven’t done all your planning, you can’t take forever to think about your business. Sometimes you fire first, and take aim later.

When she was living in a shelter with her two children, it would have been easy for Cynthia Wake to give up her direct sales business, The Hosiery Stop. In fact, it would have made sense to quit. But Cynthia doesn’t believe in giving up, and she’ll tell you the price she’s paid to persevere as a business owner. Meanwhile, when his economics professor marked an F on his business plan for Campus Concepts, you might have thought Ian Leopold would get a job and forget his idea about launching a series of campus guides. But 100 guides later, and $10 million in annual revenue, is proof enough that it pays to believe in yourself and your business, even when no one else does.

Microentrepreneurs build businesses and people run them. David Schlessinger, who founded Encore Books when he was a college student, explains the wisdom of believing in people if you want to build an empire. Earl Tate shows you what happens when you build an empire and run out of money, as he did twice. The founder of Staffing Solutions, a temporary employment agency, readily admits his mistakes so that you might avoid them.

Terri Bowersock, founder of the world’s largest consignment furniture chain, Terri’s Consign & Design Furnishings, has mastered the course on attracting customers. Years ago, teachers and friends said Terri couldn’t have mastered much of anything. Now she’s sharing her mastery with others, and helping them build successful businesses. Ev Harlow, who became a graphic designer while he served Uncle Sam in the Air Force, has mastered the course on generating profits. With no business experience at the time he launched Art Reproduction Technologies, he quickly discovered that a business without profit will soon perish. He didn’t waste any time learning the importance of making profit and how to do it.

Whoever said it takes money to make money was dead wrong, and the microentrepreneurs in this book prove it. For example, after many years of teaching string instruments in public schools, Paulette Ensign was bored and unhappy. She spent $50 to buy two classified ads in her local newspapers and created Organizing Solutions, a little business to teach people how to organize their lives, their homes, and their jobs. Carlos Aldana was twenty-eight when he left Colombia and arrived in the United States without a job or so much as a penny in his pocket. He worked three minimum-wage jobs before he started his own delivery service. Now he owns a restaurant in New York City.

Michael and Jamie Ford were middle-class Americans before an accident forced Jamie out of work. The family had to move into a travel trailer and collect welfare to exist. If only they could start their own business, they were sure they could get off public assistance and return to their former mainstream lifestyle. When a nonprofit organization that assists microentrepreneurs loaned the Fords $250, it was all the help they needed to start a tiny business selling kettle corn. Since then, the U.S. Small Business Administration has honored the Fords as Entrepreneurs of the Year in New Mexico.

Jeremy Wiener invested little more than gas and phone money to start Cover-It, a business that provides book covers to schools in all fifty states. From so tiny an investment, his business employs ten people and it will soon generate in excess of $2 million annually. Charlotte Colistro Brown, another schoolteacher, invested $200 in materials that she used to make crafts in her home. Her business, Collectable Creations, sells products that retail for $8 to $70 each. A cadre of sixty home-based employees sews and finishes the crafts. The company will soon exceed $2 million in annual gross sales!

Nancy Bombace invested $4,000 to start a honeymoon registry service, an alternative to the traditional department store registry for brides. Now wedding guests can find out where the newlyweds will honeymoon and then pay for the wedding suite, or buy dinner, a bottle of champagne, or a romantic tour. In Alexandria, Virginia, Terri Symonds Grow researched all-natural products and treatments for animals and then invested $1,500 to begin PetSage, a catalogue company that specializes in natural alternative therapies for pets. She’s watched her company’s sales grow from $30,000 to nearly $350,000!

As you read the stories in the chapters ahead, you’ll see that these microentrepreneurs represent a good cross section of the American population. You’ll also discover that we share many commonalities. With only a few exceptions, we grew up in lower-to-middle-class homes where both parents had to work. All of us learned how to make money before we were teenagers—a couple started businesses in elementary school. Most of us tolerated school, and several performed poorly. At least three continue to suffer from dyslexia. Five never attended college; four others attended but did not graduate. Six of us began our businesses while we were in college, and five of us started our businesses before we were twenty. Seven of the microentrepreneurs are women, while four of the men started their businesses with help from their wives. Feeling sorry for ourselves, or claiming to be victims of impoverishment and sometimes cruel circumstances, was not part of our routine. The world owed us nothing. Therefore, if we saw an opportunity, we grabbed it. And we still do.

The most interesting common denominator that we share, however, is that we started our businesses with small amounts of money. Two had as much as $10,000. One started with $5,000. All of the others, including me, started with less than $5,000. Ten started with $200 or less! Four got started with loans from microlenders, which are quietly popping up across the United States. (I’ll tell you more about microlenders later in the book.) Four borrowed money from family members, and two, including me, borrowed money from a friend. The other half started their businesses with no money, or their own pocket money.

Collectively, I think you will agree these stories weave a fabric of promise and fulfillment, laced with inspiration and possibilities for your own future in business. As you read the lessons and stories in the book, I expect you will find yourself saying, over and over again, I can do that, too. You can! It’s really only a matter of deciding to do it.

From there, Start Small, Finish Big has something more to offer you. My real reason for writing this book, beyond giving people the confidence to start a business, even if they don’t have much money, is to support the microenterprise movement that’s underway not only in the United States, but in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. In these countries, people who have no business experience, and no collateral to borrow money, including the poorest of the poor, are able to get capital from several hundred organizations. It’s a relatively young movement that’s gaining momentum, and as it expands, it can potentially help tens of millions of people.

My introduction to microenterprise occurred in 1989 while watching a segment of 60 Minutes. That Sunday night, as I sat at home in front of my television, I learned about Muhammad Yunus, Ph.D., an American-trained economics professor who had become a giant among impoverished people in Bangladesh, a country which 60 Minutes described as “the world’s graveyard of good intentions.” Dr. Yunus was loaning small sums of money to poor people, who in turn changed their lives for the better. Interestingly, the improvements initiated by Dr. Yunus contradicted the economic theories that he taught in his classrooms. In fact, he told 60 Minutes those theories—which he learned in America—did not work in Bangladesh. In spite of what he taught his students, economic progress did not occur the way the textbooks promised. Instead of things getting better, they only grew worse.

That’s when Dr. Yunus took matters into his own hands. He believed in a bottom-up, rather than a top-down, approach to helping people. If given an opportunity, Yunus surmised that people could do more for themselves than any government could do. So he left the classroom in 1976 and walked into the villages to really study economics. Soon thereafter, he was granting small loans to impoverished people. At the time of the 60 Minutes report, Dr. Yunus had loaned $100 million to 500,000 people in Bangladesh. The only prerequisites to qualify for a loan were impoverishment and the desire to work hard. The average loan amount was $60. Many borrowers received consecutive loans, renewed annually. (Today, Dr. Yunus’s organization has loaned more than $2.7 billion to 2.5 million people. The average loan amount is approximately $180.)

To many people who watched the 60 Minutes report, this story may not have made much sense. How could it? What kind of business could you start with $60? Could it become a business of any significance?

Yes! Even in the United States, as you’ll soon read, significant businesses have been started with $60 or less. In Bangladesh, $60 is a lot of money. A stool maker, for example, turned a $6 loan into a daily profit of $1.25, up from earnings of just 2 cents a day prior to the loan. With $30, another borrower purchased a loom and eventually earned $1,500 a year—enough money to afford a house and to educate several children. The 60 Minutes report abounded with these amazing stories of success.

While others looked upon Bangladesh as a classic case study in poverty—people were poor because they did not want to work—Professor Yunus saw something remarkably different. People were poor because they lacked resources. They had no money to do anything for themselves. Those who had access to resources were forced to pay outrageous interest rates on a daily basis to local traders. Consequently, people remained impoverished one generation after another. Provide the resources, as well as hope and encouragement, Dr. Yunus reasoned, and people could alleviate poverty on their own.

So he went to work to find money for poor people to help them start their own businesses. He didn’t want to provide aid to individuals, in spite of the fact that Bangladesh got plenty of international aid. He wanted to provide credit, which he believed was a fundamental human right. But when he contacted the community banks and suggested they loan money to poor people, who had no collateral, the lenders laughed at his idea. Of course, the reaction would have been the same from banks in the United States. Banks require collateral to make loans, and they rarely grant small loans. That’s one of the reasons I’m supporting microenterprise. By establishing microcredit lending groups across the United States, we can help people bootstrap their way into business.

After several banks rejected Dr. Yunus’s idea, he established a bank of his own. By soliciting loans and grants internationally, he founded the Grameen Bank, which in Bengali means the “rural bank.” Its sole purpose is to loan money to the “poorest of the poor.” Impoverishment is the only qualification a borrower needs to do business at the Grameen Bank.

Within a period of a few years, Muhammad Yunus had delivered more hope to crisis-ridden Bangladesh than any man or woman before him. By empowering people with tiny sums of money, and a few skills, he showed them how to help themselves. In so doing, he didn’t eradicate poverty, but he helped reduce the ravages of its horrible condition and he helped train legions of people who started grassroots businesses. Years later, President Bill Clinton would honor Muhammad Yunus in Washington, D.C., and state that he should be awarded a Nobel Prize.

While I sat fascinated by Dr. Yunus’s story, I couldn’t help but connect my own circumstances with the microenterprise movement that he inspired. I was not among the “poorest of the poor” when I started my business. But I had no money at the time, no collateral, and no business savvy. I was a seventeen-year-old kid who needed to find a way to pay for his college education. I needed resources. When a family friend offered me a small loan to start a business selling submarine sandwiches, it made all the difference in my life. As I sat there watching how Dr. Yunus changed the lives of people across Bangladesh, I understood how a small amount of money could change a person’s life forever. That’s when I decided that I would eventually help spread the gospel of microenterprise so that others could benefit from the movement, and perhaps contribute to it, too.

Third World countries were quick to copy Dr. Yunus’s somewhat controversial program, but several years passed before a Yunus-inspired organization arrived in the United States. (Other microenterprise groups already existed in the United States, however.) Critics, particularly in the U.S., have said the Grameen Bank doesn’t work, in spite of the fact that at least 95 percent of its loans are repaid on time!...in spite of the fact that its borrowers have saved more than $100 million, all of it on deposit at the Grameen Bank!...in spite of the fact that in nearly twenty-five years of development, the Grameen Bank has helped two and a half million people and spawned profit centers, including fisheries, and a cellular phone business...in spite of the fact that the Grameen Bank has demonstrated its ability to help people nourish their self-esteem, and provide for themselves and their families! “Poor people aren’t smart enough to start businesses,” say the critics. “If anything, they should be trained for employment. You need big businesses to really help people. Small businesses don’t amount to much.” Perhaps a few of the stories in this book would change their minds.

Fortunately, the critics have not discouraged Dr. Yunus, or his legion of admirers and supporters, who continue to help people start their own businesses. In recent years, the Grameen Bank, and organizations similar to it, have won favorable attention from major media, including the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, Forbes, U.S. News & World Report, and The Economist. Support for these various organizations has come from numerous groups and corporations, including Citicorp, Arthur Andersen, AT&T, NationsBank, Microsoft, Discover Card, the Ford Foundation, the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, J. P. Morgan & Co., BP America, Rotary Clubs, and Kiwanis Clubs.

More support is needed, of course, if the microenterprise movement is to flourish in North America. Much of the support will have to come from individuals who are committed to the success of small enterprises. I committed the time to develop this book because I want to be counted among those individuals. I am proud to be donating 100% of the proceeds from this e- book to the Grammen Foundation so they can continue their great work.

Today, approximately 100 organizations in the United States loan small amounts of money—rarely more than $5,000—to people who are ready to join the world of the microentrepreneur. Many, but not all of these organizations require their borrowers to be low-income. Once you know how to access these organizations, some of them may be willing to assist you, not only with money, but with business training, too. Also, many of these organizations rely on volunteers to help them work with their borrowers, representing yet another opportunity to get involved with microenterprise.

Before I tell you the story of how I started Subway Restaurants, and then share with you the Fifteen Key Lessons, I also want to tell you what you won’t learn in Start Small, Finish Big. This isn’t a book about writing business plans or about how to get your idea funded by investment bankers. This isn’t a book about business strategies or cutting-edge research. It’s not about breakthrough developments or technical prowess. It’s not about styles of management. It’s not about franchising your business, although it includes information about franchising. It’s not about my “clever strategic plan” to build Subway—because such a plan never existed—or my “incredible business skills”—because they were minimal when I started my business.

Start Small, Finish Big isn’t about building a multinational company, or even a big company. The size of the business doesn’t matter. The BIG in the book’s title may mean a part-time venture, a home-based business, or a kiosk at the mall. It could also mean a chain of stores, or an international corporation. BIG is however big or small you define it to be. It may simply describe the incredible feelings of accomplishment and pride that you derive from your own business, no matter how big it gets.

Some people may find it hard to believe that you can start a meaningful business with a little bit of money. I don’t blame them. Roll-ups, international buyouts, industry consolidations, and dot-com companies are the meat and potatoes of the business press these days. There doesn’t seem to be much opportunity for the small enterprise. And yet, it exists. Small businesses abound. The small business is the backbone of the American economy and it will continue to be the future of this country and many others. Small businesses create more jobs every year in the United States than do big businesses. As many as 40 million Americans now work from their homes, and the majority of them are small business owners. In the age of the megadeal, there’s still room for the small businessperson. All you’ve got to do is look for it, then reach out and grab it.

When I started Subway in 1965, no one told me that I couldn’t succeed with just a little bit of money. Of course, at the time, I was just a teenager, recently graduated from high school. I really didn’t know much about running a business. I knew nothing about making sandwiches, nor the food industry. I knew nothing about franchising. One day, when a family friend encouraged me to start a business, I became one of those millions of people who think about starting a business at any given time. But I also became one of the few who took the first bold step. Fortunately for me, and for an ever-increasing number of people worldwide who are part of the Subway family today, I didn’t know that you couldn’t start small and finish big.

Now that I have, let me help you get started!