Читать книгу Start Small Finish Big - Fred DeLuca - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

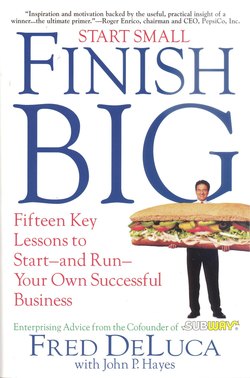

chapter three My Story

ОглавлениеHow a seventeen-year-old kid from “The Projects” started Subway Restaurants with a microloan of $1,000.

This story could have happened to almost anyone, anywhere. Carmela Ombres and Salvatore DeLuca just so happened to live in Brooklyn in the 1940s. One day they met, and not long thereafter they were married. In 1947 they had a son, and that was me.

For the first several years of my life we lived in the basement apartment of a two-family house. It was a humble, low-rent apartment, something that newlyweds could afford. When I was five, we moved to the Bronx to a new development, which everyone called “The Projects.” It was public housing, one of many similar developments built after World War II. For the DeLuca family, it was a step up!

When I was ten, my dad’s employer, Empire Devices, moved its manufacturing facility 120 miles upstate to Amsterdam, New York. Since my mother had just given birth to my sister, Suzanne, and since my father’s job was fairly secure—he was the foreman of a small production line—we left the Bronx for a small apartment in Schenectady, near Amsterdam. And that’s where we met Pete Buck and his wife, Haydee, who soon became close friends.

It was an unlikely friendship in my estimation. Pete was a brilliant scientist who had earned a doctoral degree from Columbia University. My dad was a high school dropout who worked in an electrical factory. It didn’t seem the two could have much in common, but they became pals—bow hunting was among their favorite pastimes—and they frequently brought their families together for picnics and parties.

The family friendship was briefly interrupted in 1964. Empire Devices moved again, this time to Bridgeport, Connecticut, and once again we followed dad’s job. Much to our delight, Pete called several months later to say that he was switching jobs and moving his family to Armonk, New York, about forty miles from Bridgeport. One Sunday in July 1965, after nearly a year’s separation, we were invited to visit the Bucks’ new home and enjoy a family barbecue. That was the day Pete and I formed a business relationship that would eventually make a huge impact in the fast food industry.

I had just graduated from high school and my only real concern was to figure out how to pay my way through college. While I was growing up, my mother instilled in me the value of an education. She not only told me how important it was to go to school, she also gave me the confidence to believe that I could graduate from high school, and college, too. But in the summer of 1965 there wasn’t much hope that I could get through college because my family simply didn’t have the money. I worked at a local hardware store as a stock clerk earning $1.25, the minimum hourly wage. It was a good job for a kid, but it wasn’t going to provide the money I needed for a college education.

The more I thought about college, the more I wondered about how I could find the money. As we pulled into Pete’s driveway it occurred to me that I might ask Pete for some advice. The Bucks lived in a large white house built on three quarters of an acre, which to me seemed like a sprawling property. I was really impressed when I saw the two-car garage with two cars parked inside! Pete must have landed himself a great job, one that paid a lot of money, I thought to myself.

It was late afternoon when I saw the opportunity to talk privately with Pete in his backyard. His young children were playing in another part of the yard with my sister. My parents and Pete’s wife were sitting at the picnic table not far from the house, still catching up with each other’s lives. As Pete and I stood in the middle of his green lawn I said, “Pete, I want to go to college, to the University of Bridgeport, but I don’t have the money. And I was wondering if you had any ideas about how I might get the money to pay my way through school?”

When I asked that question I had a secret hope that Pete might offer to loan me the money and tell me to pay him back after I graduated. After all, he had known me for half my life and he liked me. Pete used to get a kick out of the way I thought through problems. He’d challenge me with mathematical games and I amused him by spitting out the answers in rapid fire. Pete knew that I was a hard worker, and while I wasn’t a straight-A student, I was competent and dependable. Once he heard how badly I wanted to go to college, and that I wanted to be a medical doctor, I thought there was a good chance he might help me financially.

But Pete looked at me, and without hesitation he said, “I think you should open a submarine sandwich shop.”

What?

Of all the possible answers, this was not one I expected. What an odd thing to say to a seventeen-year-old kid, especially one who came from a modest home where no one had ever owned a business. Sure, I had my own paper route and I participated in Junior Achievement where I learned a little about business, but I was just a kid! I didn’t know what to say. Fortunately, my natural curiosity took over, and before I could say yes or no, I heard myself asking Pete: How does it work?

Pete explained the submarine sandwich business very simply. He said that all I had to do was rent a small store, build a counter, buy some food, and open for business. Customers would then come into the restaurant, put money on the counter, and I would have all the money I needed for college. To Pete, it was just as simple as that, although Pete had never owned a business nor run a sandwich shop himself.

Thinking now about our conversation it’s almost unbelievable. We were just two guys at a Sunday afternoon barbecue, speculating, really, about something we knew little to nothing about. Under similar circumstances I can imagine a teenager thinking Pete’s idea was impractical, or impossible. Or another teenager might easily have shrugged him off and quipped, “Good idea, Pete, but not the idea I was looking for.”

The more Pete talked about the sandwich shop the more I could see myself opening such a shop. Pete recognized my enthusiasm and eventually said, “Fred, you sound like you’re interested in this idea. If you want to do it I’m willing to be your partner.”

Pete’s offer caught me by surprise, but it didn’t take me long to figure out it was a great opportunity for a kid from “The Projects.” Of course I was interested! Besides, I didn’t have any other ideas, or any better offers to choose from, so I said, “Sure.”

Next thing I knew Pete walked into his house and returned with a clipping from an upstate New York newspaper. It was that clipping, I would soon understand, that got him thinking about the sandwich business. We moved from the yard to the picnic table to include the other adults in our conversation. We all listened as Pete read an article that a year or so earlier featured Mike’s Submarine Sandwiches, a familiar name to all of us because when we lived upstate we had frequently enjoyed Mike’s sandwiches. The story explained how a hardworking entrepreneur named Michael Davis opened thirty-two restaurants, mostly submarine shops and a few roast beef sandwich restaurants, in ten years. He started with almost nothing and created a mini-empire in upstate New York. The reporter related some of Mike’s struggles as well as his many triumphs as king of submarine sandwiches in his part of the world. When Pete finished reading the article he looked up at us and wondered: “If Michael Davis can do this, why can’t we?”

I now know that the question didn’t come out by accident. Pete wanted to set a long-term goal beyond the opening of one store. When no one could think of a reason why we couldn’t perform as well as Michael Davis, we began discussing what we could accomplish. That’s how we set a goal to build thirty-two submarine sandwich shops in ten years!

The importance of that goal didn’t immediately register with me. I was still thinking about how to open the first store. I just wanted to get through college. I didn’t really plan to make a career of the sandwich business. But nonetheless, we set our long-range goal, and eventually the significance of those numbers would become meaningful.

During that night we also spent several hours discussing our menu. We thought Mike’s menu was a good one. It consisted of seven foot-long, cold sandwiches, and we decided to offer a similar menu. However, Pete then told us about Amato’s, his favorite sub shop in his hometown of Portland, Maine. Pete thought Amato’s sandwiches had a better taste profile than Mike’s. At Mike’s, they only put onion, lettuce, and tomato on their sandwiches, along with meat and cheese, but Amato’s included pickles, peppers, and black olives, without the lettuce. We talked about visiting Amato’s in the near future.

Amazingly, we even established the prices for our sandwiches! Like Mike’s, our prices ranged from 54 cents to 69 cents. It just never occurred to us that it didn’t make sense to set these prices before we knew a thing about our food and operating costs.

As we were getting ready to leave the Bucks’ home that evening, Pete asked us to wait for a second. He then pulled out his checkbook and he wrote a check for $1,000. That was his investment in our new venture.

On the drive back to Connecticut with my family, little did I know that if I succeeded at opening a submarine sandwich shop I would accomplish more than funding my college education. Success would mean financial independence and everything that comes with it, not just for me, but for many other people around the world. Success would mean adventure and excitement on a nonstop roller coaster that would eventually be called Subway. But on this particular ride home, I wasn’t looking very far into the future. I was thinking about the next morning when I would set out to find our first location.

Getting Started

When I tell people about my backyard conversation with Pete Buck, explaining that I had agreed to open a submarine shop even though I didn’t know how, they frequently ask me, Weren’t you afraid of failing? Failing never entered my mind. If other people had opened submarine sandwich shops I thought there was a reasonable chance I could do the same thing.

The next morning I drove my dad to work so that I could borrow his car. Pete said the first step was to find a small store, and while I really didn’t know how to do that, it didn’t take me long to find exactly what I thought we needed. It was right around the corner from United Hardware, where I was employed as a stock clerk. I called the landlord and arranged to inspect the shop on Saturday, when Pete could join me. That afternoon I reported to work at the hardware store as I did every workday until we rented the first location.

It would take a few months before Pete and I realized that I hadn’t done a very good job of finding our first location. When I looked for available shops, I just drove up and down the familiar streets without even considering other parts of town. I simply didn’t know any better. I didn’t know there were certain characteristics that made one location better than another. Consequently, I didn’t know what was wrong with the location we were about to inspect, and neither did Pete. I had worked at the hardware store for several years and never noticed the location before. I should have realized that if I hadn’t noticed the location customers would have a difficult time finding it, too.

On Saturday the landlord met us at the shop shortly before noon. We walked inside and found approximately 450 square feet of space. Pete and I were impressed: The store was clean and neat and we wouldn’t have to do much to get the place ready for business. The ceiling and tile floor were in good shape. We would have to add a counter for making sandwiches, and build a partition to block off the storage space in the back of the store, but we had already figured as much. Otherwise, the shop looked acceptable to both of us.

“What do you think, Pete?” I asked my partner in earshot of the landlord.

Pete said, “How much is it again?”

“One sixty-five a month,” the landlord responded.

Pete nodded yes. He liked it.

“Okay, let’s have a lease drawn up,” the landlord continued.

“Lease? What’s that?” I asked.

The landlord explained that the lease was a legal document that spelled out the terms of our agreement and would establish the rent at $165 a month for two years. It was a protective measure for both of us, he said, adding that it would cost about $50 to hire a lawyer to prepare the document. “We’ll split it,” he said.

Neither Pete nor I knew anything about leases, and all I could think about was the $25 that we’d have to pay the lawyer. That was 2.5 percent of our capital, and that was more money than we could afford.

“I think we’ll just take it without a lease,” I responded.

The landlord didn’t object. Of course, he was a guy with a crummy location that he needed to rent. On the spot we paid him $330, the first month’s rent and a month’s security deposit. He handed us the keys, and that’s how we rented our first store. It took about five minutes.

As soon as the landlord collected his money he was on his way and Pete and I were left to design the restaurant. That took us another five minutes. We knew we needed a spot for the cash register, space to prepare the food, a partition to block off the storage area, and a counter for customers to lay down their money. I would recruit a friend from high school to help me with the construction. Pete reminded me that we’d also need an outdoor sign, a cash register, and some miscellaneous equipment, and that was it, perhaps another five minutes spent discussing restaurant design before we left and locked the door behind us. We ate lunch together, discussed some other ideas, and Pete drove back to Armonk.

It’s easy now to say that we rushed into the deal, or that we were carried away by the excitement of our new enterprise. I certainly should have conducted a wider location search and I probably should have signed a lease. However, we were just getting started, and college was opening soon so it was important to take action. Rather than sitting around making plans for the rest of our lives we decided to just go ahead and do it. Pete and I were, and still are, the type of guys who like to make decisions without belaboring things. From my perspective today, taking action is a good quality and I’m glad we took that first location. Sometimes, knowing less and actually doing something is far better than knowing everything and never doing anything at all.

The Submarine Sleuths

Funny thing, until I was face-to-face with our first customer, I had never made a submarine sandwich. Nor had Pete. We enjoyed eating them, and we knew they consisted of meat, cheese, vegetables, oil, and bread, but we had absolutely no experience making them. So it was important that Pete took the time to drive my mom and me to Portland, Maine, where we decided to research the fine art of making submarine sandwiches. Although we were familiar with Mike’s in upstate New York, we needed to experience another taste profile, and also watch the process of making sandwiches.

Pete had grown up eating submarine sandwiches at Amato’s Italian Deli, and he remained fond of their product, so he suggested that we visit his parents in Portland and spend some time hanging out at Amato’s. My mom decided to join us, and we appreciated her company, especially because she knew much more about food than we did.

We arrived in Portland in time for dinner and decided to begin our research the next day around noon. From outside Amato’s front window we gained a vantage point from where we could watch the action behind the sandwich counter. After a few minutes we decided to go inside to gain the experience of being a customer. We ordered our sandwiches, paying attention to the entire process of ordering and making the sandwiches. We then took our sandwiches outside and resumed peeking through the window. We paid particular attention to the process of cutting the bread, laying in the meat and cheese, and applying the oil. One of the things we noticed was that Amato’s people poured oil onto each sandwich from a gallon can. Our trio, in spite of our inexperience, thought that was clumsy. We immediately decided it would be better to transfer the oil into smaller containers, the size of a small pitcher, then pour from the containers onto the sandwiches, thus making the operation a little easier. Later we discovered our idea also added expense and created inconsistency!

There was only so much we could learn from Amato’s. They only sold two variations of sandwiches—ham and salami—so we decided to visit several other sandwich shops that day. We bought sandwiches at each shop, observed their operations, and evaluated what we perceived as the pros and cons. Between visits we compared notes.

Within twenty-four hours, our research, sparse and unscientific though it was, provided what we thought was sufficient information to make some key decisions. Essentially, we had two prominent profiles to consider for our business: Amato’s and Mike’s. The two had little in common and that was a plus because it gave us different perspectives. Mike’s variety of sandwiches included cheese and tuna. Amato’s sold only the two sandwiches. We liked variety, so we stuck with our earlier decision to sell seven different cold sandwiches.

We preferred Amato’s taste profile, but we also preferred Mike’s bread. Amato’s used a nine-inch soft roll, but Mike’s was a foot long, and that sounded good to us. Amato’s added a larger variety of fresh vegetables to their sandwiches. Mixed with oil, the fresh vegetables added flavor to the sandwich, so we decided to include them. The foundation of an Amato’s sub was like an Italian salad without lettuce, and that was very much to our liking. We decided to imitate Amato’s sandwich and put it on a foot-long roll, but we would sell a greater variety of sandwiches, just like Mike’s.

Even though we didn’t know anything about costs, we stuck with Mike’s pricing scheme. After all, as good as it was, there was only one Amato’s, but there were thirty-two Mike’s! We figured Mike’s must have been doing the right thing with pricing, but the fact that Mike’s combined thirty-two restaurants’ worth of volume and had far greater buying power wasn’t even a consideration for us. What did we know about volume?

That was the sum and substance of our research. It was really simple. Could we have done more? Certainly. Would it have made a difference? Probably. Observation is a terrific tool, but when you don’t know any better, you can see something that’s obvious and not know what it means, or you can miss a critical component. Something like pouring oil on sandwiches is a good example. When we watched Amato’s people poke a small hole in the top of a gallon can and lift that heavy can each time they wanted to pour oil on a sandwich, we thought there had to be an easier way. That’s why we decided to use small pitchers. However, the secret to pouring the oil from a gallon can with a small hole in the top is control and consistency. By making the hole a certain size, Amato’s could control the amount of oil per sandwich. With our pitcher, we had no control. The amount of oil we poured on each sandwich depended on how far we tilted the pitcher, and for how long. Consequently, our oil costs and product quality varied from sandwich to sandwich. But that’s not something we would have understood simply by observation. We had to try it ourselves before we realized there was method to the madness.

Intuitively, we realized that to really understand our business, we would have to begin to work it. It didn’t matter if we chose Amato’s pricing instead of Mike’s, and Mike’s taste profile instead of Amato’s. If we made mistakes—and we did—we could correct them as we progressed. We realized that we were starting a small business. It was a tiny investment of money. We didn’t have much to lose. If there ever was a time to experiment, it was now. Indeed, other people were already operating similar businesses, and it was so easy to go see what they were doing. Why would we spend our limited time and capital on research?

When we had 14,000 restaurants, we spent $70,000, a modest amount of money for this kind of research, that worked out to just $5 per restaurant. What a bargain! When we were just getting started, we couldn’t get much research for $5, and we couldn’t have afforded much more than that. Therefore, we did what we could as quickly as possible without getting hung up on what we didn’t know. And there was plenty we didn’t know.

Today, however, it’s a different story. For example, to introduce something as simple as a new cookie formula in our Subway restaurants, we invest months of time and tens of thousands of dollars in the research. We might send researchers into five or six regions in North America to hand out cookies and ask detailed questions to gather information about perceptions and preferences from consumers. We then hire experts to correlate mounds of data in anticipation of finding the perfect cookie for our customers.

Preparing the Restaurant

On the way back from Maine we targeted Saturday, August 28, 1965, for the opening of our restaurant. That meant I would devote all of August to preparing for the big event. With some help from my parents, and my high school friend Art Witkowski, who wasn’t doing anything that summer, I purchased equipment and supplies, contacted vendors, built a counter and an outdoor sign for the restaurant, and drummed up future customers by handing out promotional flyers.

Oh yeah, Pete and I also came up with a name for our business. As we looked at the stores adjacent to our shop, there was Ann’s Bakery, Judy Blair’s Dance Studio, and Suzie’s Yarn Shop. All of the businesses were identified by a person’s name, so we arrived at the logical decision to call our business Pete’s Submarines, but we decided to glorify the name by adding the word “Super.” Thus we became Pete’s Super Submarines! Occasionally we had to shorten the name to the less glorious Pete’s Submarines to make it fit on our outdoor signs.

However, we later discovered the name wasn’t easy to communicate. When people heard the name Pete’s Submarines over the radio, they often thought they heard the words “pizza marine.” When consumers who had never been to our restaurants began asking me “What kind of pizza do you have? Is it seafood pizza?” I knew we had a problem.

I was driving in my car one day thinking about our name and what to do. I wanted a name that was short, clear, and difficult to mispronounce. I wanted to use “sub” in the name because it was a crisp, short way to say submarine. And suddenly, the word “subway” popped into my mind. We changed the name to Pete’s Subway, and eventually to Subway, but not until after opening several restaurants.

While my buddy Art helped me get the shop ready for opening day, my mom helped me line up the various vendors who would provide the bread, paper goods, meats, vegetables, and cheeses that we would need. Without anyone to guide us in these matters we consulted the local Yellow Pages and my mom and I were sort of like the blind leading the blind. With a name and an address in hand, off we’d go to tell our story to any vendor who would listen. I’m sure these vendors had never witnessed anything quite like it before. A pretty, little Italian woman and her lanky teenage son show up with plans to open a sandwich shop so he can afford to go to college. They say their goal is to open thirty-two restaurants in ten years! It’s not a story they heard every day.

We must have been a convincing pair, however, because no one turned us away. I am sure they took me more seriously because mom was with me, but the process was fairly simple. I think it’s the type of thing that anyone could have done in almost any community. In nearly every town there are suppliers and most, if not all, of them need more customers. And even if mom and I seemed a bit unusual, and our business a bit risky, the suppliers were willing to work with us. We registered our most complicated request at the bakery. We wanted our rolls custom-made. But the baker said even that wasn’t a problem. Everything was cut-and-dry. After all, what’s to buying vegetables, meats, cheeses, or paper products? The suppliers simply sold us what they had in stock.

Of course, we had absolutely no purchasing power, but we never worried about it, either. We simply had to pay high prices for whatever we needed to buy, but any small business faces a similar predicament. There wasn’t anything we could do about it. However, the vendors didn’t require payment in advance. They gave us credit on the spot! We could have shopped around and looked for better deals, but that would require more time. It was more important to line up what we needed, buy it, and figure out how to get it cheaper at a later time.

Now that I wasn’t working at the hardware store, I had no income, so time was a major issue. Every day that our restaurant was closed I was losing money, and so was the business. There was not only the cost of ongoing rent and utilities, but also the lost opportunity. If the restaurant wasn’t open, we couldn’t sell anything. If the restaurant wasn’t selling anything, I couldn’t get paid. My singular focus was to get the restaurant open.

Of course, the location couldn’t open without equipment, so while my mom helped me find suppliers, my dad helped me scour the newspaper classifieds every day for used equipment. We needed a cash register, a refrigeration unit, a commercial sink, a meat slicer, and some countertops and shelves. We found it all, even on our shoestring budget. Most of it was obsolete, but it was functional and it lasted for many years. My most unusual purchase was a big, brass cash register. When we pressed the number keys, two or three of them simultaneously, the price popped up with a “cha-ching” in the top of the cash register, and the drawer opened automatically. It was so old that the highest dollar amount it could ring up was $2.99. That wasn’t a problem, though, because our highest-priced sandwich was 69 cents. For the purpose of collecting money and making change, that piece of junk was all we needed.

Opening Day

On Saturday morning, Art Witkowski and I had no idea what to expect when we opened at nine to prepare for customers. One of us cut up the vegetables: onions, tomatoes, green peppers, and even olives, while the other sliced the ham, cheese, and salami, a half pound of each. A half pound seemed right to me because that’s the amount mom would ask me to buy when she sent me to the store for our family.

By 9:30 we were ready for business and patiently waiting when a young neighborhood girl rode up on her bicycle. We smiled as she walked in and ordered the first sandwich. This was a critical moment in the history of Pete’s Super Submarines, but not for the obvious reason.

Yes, it was our first sale, but now I had to teach Art how to make a submarine sandwich. Even though I planned to go into the sub business, and I traveled to Portland to watch Amato’s, and I rented and built the store bought the food and equipment, I had yet to make a single sandwich. And that wasn’t the worst of it. Within an hour I had to leave Art in charge of the restaurant. Coincidentally to our opening day, the University of Bridgeport scheduled an English capability exam at 11:00 a.m. for entering freshmen. I had to take the test, and that meant I had to leave Art alone in the restaurant for a couple of hours. Pete, his wife, and my parents planned to help out later in the day, but until they arrived, or I returned, Art would have to handle things on his own. That meant he had to know how to make sandwiches.

Actually, making sandwiches didn’t seem to be too difficult. By the time we had left Maine a few weekends earlier, we had thoroughly discussed the details of how to make our sandwiches. We talked about how to cut the bread, how to layer the meat and cheese, the vegetables, the oil, and the seasonings. As Art watched me that morning, he didn’t think it was much of a challenge, either. Good thing, because our first customer was our last customer before I left the restaurant. Art was on his own with one sandwich worth of training.

At approximately 12:20 p.m., the English exam now a successful but distant memory, I returned to our restaurant parking lot and it was packed. As I glanced over at the shop I couldn’t believe my eyes. Not only were customers crammed inside, they were standing in line outside! It was the noontime rush, and all I could figure was that a lot of people had come to the restaurant, or the service was very slow. As it turned out, it was a little of both.

Walking across the parking lot I spotted my partner. “How you doing, Pete?” I said with a measure of excitement in my voice. I noticed he was carrying a brown bag. “What do you have?” I asked.

“Knives,” he responded. Pete had arrived earlier and discovered that we only had one knife for slicing vegetables and making sandwiches. “We can’t serve all of these people with just one knife.”

Having worked at a hardware store I knew there were many types of knives, all priced differently, some cheaper than others. Pete had purchased two knives at $3 each and I cringed. That was going to put a crimp in our budget, but there was no time to do anything about it. We rushed into the restaurant and went to work, furiously taking care of customers.

Since we didn’t know anything about establishing an operational system, we didn’t have one that first day, or for many weeks thereafter. Consequently, we had a continuous line of customers and we were behind the eight ball. It didn’t help matters that our tiny shop was designed as a one- or two-person operation and there were now six people working in it: Pete, his wife, my parents, Art, and myself. As best we could, we each found a place to work. Art had transferred his masterful sandwich making training to the others, so they were busy behind the sandwich counter. I walked to the back room where we had several bushel baskets of green peppers. I turned over one empty basket for a place to sit and used two full baskets to support a piece of plywood that served as a table where I could cut vegetables. Then I went to work replenishing the vegetable supply at the counter.

The line out front never gave out and every so often I took a curiosity break to see who was in the restaurant. Occasionally a friend came out of the line to congratulate me, and I immediately took advantage of the opportunity. “Let me give you a tour,” I’d say. Then I’d proceed to explain, “This is the counter we built. Here is the cash register. Over here is the partition we built to hide the back room, and”—pointing now to my makeshift work station—“here’s where I’m cutting vegetables. Why don’t you have a seat here and help cut some vegetables?” I recruited five more people out of the line to help us that day.

By 5:30 in the afternoon mom told me we were nearly out of food. We had sold almost all of the rolls, twenty-five dozen, and we were low on meat and cheese. So I ran out to an Italian deli to buy more supplies. It was late in the day, however, and I returned with only another dozen rolls. Within an hour, we ran out of food, but fortunately, we also ran out of line at the same time. We had planned to remain open until 11:00 p.m., but at 6:30, having sold 312 sandwiches, we closed the doors. What an unbelievable day!

When the last customer had left, and our group started cleaning up, Pete and I moved outside to sit on the curb at the edge of the parking lot. We had that exhausted-but-satisfied feeling that athletes experience when they win a big victory. As we reviewed the day, we could hardly believe our success, and our anticipated good fortune.

“If all of these people showed up today,” I said exuberantly, “and hardly anyone knows we exist, imagine tomorrow!”

“They’ll all come back and the next time they’ll bring their friends. We’re going to do great. We’re going to be millionaires!” Pete said confidently.

Reveling in the glory of our opening day success we couldn’t help but think the customers loved our restaurant. All we had to do now was build more restaurants and attract more customers.

Of course, it wouldn’t work quite that way. There was a challenge around every curve, and the first curve was just ahead. We soon discovered that while we sat on the curb that day, we had committed the sin of counting our chickens before they hatched!

Monday Night Quarterbacks

Several days after we opened Pete’s Super Submarines, I entered the freshman class at the University of Bridgeport as a commuter student, and possibly the only student who owned a small business, although that meant nothing to me at the time. Even with a full load of sixteen credit hours, I managed to arrange my schedule so that I attended classes in the mornings, worked in the shop in the afternoons and early evenings, and studied at night. Some days it was possible to study in the shop, but I didn’t look forward to those days because it could only mean that business was slow.

Mine was a busy schedule, but not especially difficult. Every day presented a new challenge or opportunity. Mondays, however, became particularly important in my routine. Following our research trip to Maine, when there was a lot of work to be done, Pete and I began meeting weekly to assess our progress and evaluate our plans. Now that our shop was open for business, a weekly meeting continued to be a good exercise to monitor our development, review our progress, and plan for the future. Each week we met at the same place—World Headquarters—also known as my mom’s kitchen table.

On Monday nights Pete left work at about five and drove from Armonk to our co-op apartment in Bridgeport. Right after six he would walk through the back door into our kitchen where my mom was minutes away from serving a spaghetti dinner, including homemade sauce and meatballs. I was there waiting for him, anticipating his first question, which he asked religiously upon arrival: “How’s business?”

I always answered with the number of sandwiches sold by 6:00 p.m. that day. A few minutes before Pete’s arrival I would call the store for an update from our employee. Pete didn’t want to know dollars and cents, only the number of sandwiches sold. If the number was high, Pete smiled. If it was low, he frowned. After I announced the number, Pete joined my family at the table and we enjoyed mom’s dinner. We made a point not to talk about business while we ate.

After our meal, as the table was being cleared, Pete would open a three-ring binder that he brought with him to every meeting. Like the good scientist that he was, Pete kept a journal to track our progress. He charted our weekly sales on a graph in his notebook, and he recorded observations that he considered important. We talked about every aspect of the business—sales, products, customers, employees, marketing ideas, and even the bills we had to pay that week. My parents participated in these meetings because they were involved in the business, even though they had other jobs. My mom knew all of our suppliers and both she and my dad helped out in the shop, particularly when I couldn’t be there.

We didn’t know it at the time but we were at a tremendous disadvantage during these Monday meetings. We were like travelers without a roadmap, or scientists without measuring tools. The purpose of our get-together was to observe, calculate, project, and analyze the business. But we were painfully slow arriving at good conclusions. More sophisticated businesspeople would have had a variety of reports and an occasional financial statement from their accountant to measure their progress, and enlighten them. But we were years away from having these tools. We didn’t have an accountant. We kept our own books, and we didn’t know how to produce a financial statement. Without business experience, we really didn’t know what to observe, calculate, project, or analyze.

For example, when we spoke about serving the customer, or the quality of our product, we weren’t able to make a good assessment of how we were doing. Obviously we wanted to serve a quality product and keep our customers happy, but we didn’t know enough about what customers wanted to adequately discuss the components of those issues. We simply didn’t know the right questions to ask.

Funnier yet, none of us necessarily had answers! Pete didn’t show up on Monday nights with all the answers. Sometimes, frustrated by slumping sales, tight cash flow, or a problem we just couldn’t solve, Pete would jump out of his chair, run to the back door of our apartment, and shout, “What’s wrong with you people here in Bridgeport? Get over to our restaurant and buy some subs!” As business neophytes, we were all inadequately trained to understand the business.

Nonetheless we plodded forward, somehow sensing that we were doing a good thing by meeting every Monday night, taking a step back from the business to conduct these conversations. And, of course, we were doing a good thing. We didn’t make great strides from week to week, but over a long period of time the cumulative knowledge we gained about our business was invaluable. Without a network of savvy advisers, or even one who had owned a sandwich shop, these meetings yielded the information we needed to build our business. The meetings presented an opportunity to learn and to prepare, to try and to try again, and to continually improve. No matter what challenge we faced, Pete and I were proactive. We looked for solutions, and we were always ready to give it another try. That was another major benefit of the meetings. They fostered a successful partnership by giving Pete and me time to calibrate our thoughts. We didn’t always agree, and we were often frustrated by the various challenges we faced, but there was never tension between us personally. There were no loud, knock-down battles or arguments of any kind. If Pete’s Super Submarines was going to succeed, we had to depend on each other to come up with the solutions and get the job done.

The Plummeting Graph

After a month or two of Monday night meetings a pattern emerged on Pete’s sales chart. The shop was busiest on Fridays and Saturdays and slowest on Mondays and Tuesdays. Sunday was an odd day. Business could be dead until 4:00 p.m. and then we’d get a surge of customers until 7:00 p.m., and then it would be dead again until we closed. The more interesting pattern emerged after several months, however, and it was neither pretty nor encouraging.

With each passing week since the opening, we sold fewer sandwiches. In other words, our sales chart was headed downhill! That record of 312 sandwiches sold on opening day had quickly faded, not to be seen again. By November, 100 sandwiches sold was a big day, but it was far from adequate. All the more disappointing, and worrisome, the numbers continued to fall.

One Monday night in late November our “brain trust” decided the restaurant lacked exposure, so we invested in the Jingle Bell Special, an advertising promotion sponsored by a local radio station. It cost us $550, an enormous sum of money, but an insignificant amount if the special could improve our December sales. The radio advertising rep convinced us that people would be out Christmas shopping all month and they’d hear our promotion and stop by for a sandwich. Indeed, people were out shopping, and certainly they heard the radio spots for Pete’s Submarines, but they didn’t stop for a sandwich. Our sales continued to fall in December, and January, too. The low point didn’t occur, however, until one cold, dreary Monday in February.

“How’s business?” Pete asked when he arrived at World Headquarters on this particular day.

“Seven,” I said.

It didn’t take the genius of two Monday night quarterbacks to know that Pete’s Super Submarines was in trouble. Even at our top price of 69 cents, sales of seven sandwiches wasn’t enough money to pay our employee for seven hours’ work, let alone cover the cost of food and rent for the day. Anyone else probably would have closed the business that night. In fact, that was the first option Pete considered, but not until after dinner.

As we began that night’s meeting, Pete picked up his notebook and I watched him print the letters: LTDATATK.

“That’s our first option,” he said.

“What does it mean?” I asked.

“Lock the door and throw away the key,” he responded.

But as soon as he said it we both decided it was a bad idea. Closing the location wasn’t what we wanted at all. It was only six months old and it was too soon to give up on it. No, there had to be other options, and there were, of course.

“We could advertise the restaurant,” Pete said.

However, as we talked about that option we remembered the Jingle Bell Special. If anything, that was proof that we didn’t know how to advertise effectively.

As our discussion continued, and we evaluated various options, we eventually settled on an idea that most people would have said was absolutely crazy.

We were pretty sure the problem was the location, and so we thought we ought to move it. We batted around the idea of finding another shop and relocating. But the more we discussed that strategy, the less we liked it. The shop was losing money. Moving it didn’t make sense. Let’s close it, we said, and just find a new location and start all over again. But that strategy didn’t appeal to us, either. If we closed our first location before we opened a second location, we might never get started again. Now that we knew the challenges of operating a submarine sandwich shop, we might not be as brave the second time.

Our meeting was running late and we thought we had exhausted our options when Pete suggested that we keep the first location and open a second shop. I’m sure that if we had consulted an accountant or a board of directors they would have said Pete’s suggestion was outrageous if not irresponsible. We had not proven that we could operate one successful submarine sandwich shop. And now we wanted to operate two?

Why?

For several reasons it made perfect sense. If we moved the current restaurant we’d have two investments. We’d have the expense of leasehold improvements in the new shop while we abandoned the leasehold improvements we had already paid for in the first shop. And then there was the equipment. It wasn’t worth moving our old equipment, especially if we had to pay to install it a second time. If we had to buy equipment all over again to relocate, then why not buy it for a second shop?

And there was more. A second restaurant would give us the opportunity to experiment and compare results. We could accelerate our learning curve in the business by keeping one restaurant as a control unit for measurement purposes. Plus—and this was a major benefit—two shops in the same market would be like advertising. People in Bridgeport might get the idea that we were so successful we were expanding, and that alone would help sales rise again. We even joked about creating a promotional flyer that said, “Thank you Bridgeport for making us so successful. We’re now opening our second restaurant!” We figured no one would know we weren’t successful because hardly anyone was coming into the restaurant!

The one negative thing about our decision was continuing to carry the burden of the original, unprofitable restaurant. How much would that detract from the success that we might achieve in our second restaurant? It was an unknown, but in the final analysis, we decided the second restaurant was worth the risk. As it turned out, it was one of the best decisions we ever made.

Blessed Be the Vendors

We needed little more than $1,000 to open a shop, and strange as it may seem, money wasn’t an issue when we decided to find a second location. Sales had plummeted in February, but due to the help of our vendors, which I’ll explain in a moment, we were not out of money. We weren’t flush with cash by any means, but I held tight to the purse strings, a practice that helped us then and has helped us many times since.

Since we didn’t have much money to start the business we never allowed ourselves to build up big expenses. We avoided buying anything that required a hefty payment on a weekly or monthly schedule. After paying the rent, the utilities, and a couple of employees, our only expense was the cost of supplies, primarily the paper goods, plus the meat and cheese, vegetables, and bread that we used to make our sandwiches. Of course we also sold soda and chips, and we paid for these products when they were delivered to our shop.

My salary was skimpy and I didn’t collect it all at once. As management, I earned $1.35 an hour, 10 cents over the minimum wage. That worked out to $67.50 for my usual workweek of fifty hours. However, after I quit my job at the hardware store, I calculated that my personal expenses amounted to only $13 weekly. So when we opened the first shop I told Pete that the business should pay me a weekly allowance of $13. Then, when tuition was due at the University of Bridgeport, about $600 a semester at that time, the business would pay that, too.

As part of the routine during our Monday night meetings we subtracted my allowance and any tuition payment from my accumulated earnings and most weeks the business owed me money. This may not sound very attractive to someone who’s thinking about starting a business, but in reality most new business owners can’t collect all of their salary at the time it’s earned. Our microbusiness remained open partly because I was willing to stick with it, to figure out how to make it work better, to work for a low salary, and at the same time delay collecting my salary. There was always the risk, of course, that the money would never be there, but that was part of the gamble in starting a business.

The real reason we didn’t run out of money, however, had less to do with delaying my salary than with the special relationship we developed with our vendors. Every Friday morning I would look at the bills to be paid and, depending on the amount of money in our checkbook, I would decide how much we could afford to pay each vendor. In the early days, we could never pay as much as we owed, which is why bills started piling up. But I always wrote a check for each of the four main vendors. Then, instead of stamping envelopes and mailing the checks, which would seem to be the efficient thing to do, my mom and I visited the suppliers with payment in hand. It was an unusual procedure. Somehow, though, it felt better visiting the suppliers, and it was good that we did because otherwise we would not have been in the position to expand.

It took about two hours for mom and me to visit the vendors, and we got a terrific return on our investment of time. Since they were all small businesses, there was a good chance the owners would be on site when we arrived and we’d have the opportunity to talk with them. We always started with a quick update about our business. Sales were slow this week, the big snowfall hurt us. But overall things are going great. And here, we brought you a check for $100. I don’t think the vendors were particularly interested in our story, but we told it anyway. Then we’d give them some unsolicited feedback about their product. With years of experience handling food, mom was particularly good at this. The bread formula was perfect this week, keep making it that way...Be sure we always get this brand of ham, it’s really high-quality...These paper products didn’t hold up. Can we try something else? Ten minutes and we were finished. However, we had one other critical point of business to handle. We didn’t leave until we placed the next week’s order, which was usually for more than the check we had just given the vendor.

By the time we decided to open a second location, we owed our suppliers several months’ worth of bills, altogether amounting to more than $3,000. It was rare that we owed them less than two months’ worth of invoices on any given Friday. In spite of that, none of the suppliers ever pressured us for money. I can only assume this had something to do with our track record. We never failed to give them at least a small payment every week. We never missed a week, and we were always up front with them. If nothing else, we had earned credibility in the eyes of these suppliers, and consequently they were willing to do more for us. As it was, we financed the construction of our second shop, and even subsequent shops, with the credit supplied by our vendors. Blessed be the vendors!

The Excitement Mounts

I had a good feeling about our second shop in neighboring Fairfield, Connecticut. It was just as bad as our first location, with poor visibility, but the rent was only $85 a month, and no sooner than we had agreed to take it, sales began to climb at our original shop. I took that as a good omen. We opened the shop on Saturday, May 21, 1966, and once again a record crowd turned out to purchase Pete’s Super Submarines. Within a few weeks sales were so strong in both of our shops that we patted ourselves on the back for the fortitude to not only remain in business, but to expand our business. The fact that the seasons of the year had more to do with our increased sales than the opening of a second shop had not yet occurred to us!

One Monday night three weeks later, as Pete and I reviewed his impressive sales chart, which was now climbing uphill, we agreed that two shops were better than one. That led us to the logical and immediate conclusion that three shops would be better than two. That night before Pete left for home, we decided to open a third location.

I found a third shop at 1212 Barnum Avenue in Stratford, Connecticut. Two vacant storefronts were next to a parking lot and I had the choice of renting the inside storefront for $85 a month, or the more visible outside section for $100 a month. The lower rental fee was tempting, since we didn’t have a penny to spare, but I decided to pay the additional $15 monthly just for the visibility. Since we had no visibility in our other locations I had a hunch visibility was worth the extra money. Fortunately, I was right.

So on July 22, less than a year after we had opened our original shop, we opened our third location, which initially was as successful as our first two. For the next six weeks, through early September, we had a thriving business, and the mood of our Monday meetings was even more high-spirited than usual. Sales were up at all three locations, proving our theory that it was better to have more restaurants than to have fewer. We were far from thirty-two restaurants, but we still had nine years to hit that goal.

But then, one Monday in late September, that ugly downhill pattern that had appeared the year before on Pete’s sales chart showed up again. Sales in all three locations had begun to follow the first-year pattern of our original restaurant. September’s sales were lower than August’s. And the downhill trend was back in force. By the winter of 1967, instead of owning one low-volume, money-losing shop, we owned three of them!

That’s when we suspected the seasonal effect to our business. Had we known anything about the fast food business, we would have anticipated the dramatic swings that occurred in sales between summer and winter. Eating out in the 1960s was not yet an everyday occurrence, and with cold weather and several holidays that consumed energy and money, people were more likely to eat at home. Consequently, winter’s sales levels might amount to just 60 percent of summer’s sales. But we had no way of knowing this at the time. All we could do was wait it out. “By spring, sales may pop back up again,” Pete said one winter night. Thank God he was right.

A Turning Point

We opened a fourth low-volume location on Park Avenue in Bridgeport in 1967, and then one Monday night in April 1968, I surprised Pete with the news that I had just rented our fifth shop. He was excited and he wanted to know where it was located, but I was saving that information until after dinner. “It’s in Bridgeport. We’ll drive over to see it after we eat,” I said, building a little suspense.

I was nervous about showing Pete our fifth location, and for several reasons. We had yet to sign a lease for any of our shops, but I had signed one this time. It probably wasn’t legal because I was underage, but the landlord wasn’t about to do business without a lease. When he told me to report to his office to sign the document, I did. I then immediately began construction on the shop. That might not have been an issue except that I also made a dramatic change to our standard decor without consulting Pete. Worst of all, however, Pete had actually seen this location two years earlier and had rejected it because there was no parking space for customers! This was the first time I had made bold business decisions without seeking Pete’s approval, and I didn’t know how he would react.

After dinner we headed toward the location in my car. Pete wasn’t very familiar with the streets in Bridgeport and I purposely drove the back roads to confuse him even further. I approached the shop from a direction that I hoped he wouldn’t recognize. “There it is,” I said, as we turned the corner from East Main Street onto Boston Avenue. “It’s already under construction, and we’ll be open in May.”

Pete looked at the shop for a moment and said, “Haven’t I seen this location before?”

I admitted that he had, and that he had rejected it.

However, I was excited. The restaurant’s visibility was incredible, so much so that I didn’t really think parking would be an issue. The location was its own billboard, particularly after dark. People coming down Boston Avenue, a heavily traveled road, could see the shop for half a mile. Tucked into a large residential neighborhood, the shop was the first commercial business for three quarters of a mile and my experience told me that was powerful! Parking didn’t matter, I was sure of it. Customers would figure out where to park.

In the two years since Pete had rejected the location I couldn’t get it out of my mind. I drove by it every day because my girlfriend, Liz, who is now my wife, worked half a mile down the road at a German delicatessen owned by her parents. Every time I stopped for the light at the corner of Boston and East Main, I would look at the location that could have been. So when the florist who rented the store failed, I decided to grab it and deal with the consequences later.

“Pete, I think it’s going to be our best location,” I said tentatively.

Pete wasn’t happy. “Without parking,” he grumbled, “customers aren’t going to come to this shop. That’s a problem.” And he wasn’t happy about the extensive decor changes, either, but he didn’t interfere.

Opening day sales of our fifth restaurant dwarfed each of our previous first-day sales. Just as I had hoped, the terrific visibility overpowered the parking problem. Customers parked wherever they could. They parked in the bus stop and they drove over the curb to park on the sidewalk immediately adjacent to the shop, and they also parked across the street in a no-parking zone. Basically, everyone parked illegally, but no one complained. As for Pete, he was no longer annoyed once he saw how much money the restaurant generated for us.

At about 4:00 p.m. on opening day, when the restaurant wasn’t supposed to be busy, I was installing floodlights on the roof to illuminate our sign. As I looked to the ground and watched the steady flow of customers coming into the shop it reminded me of our original opening day when Pete and I sat on the curb counting our chickens. This time, however, I was counting customers, and I was certain this shop would become our strongest producer.

In fact, the Boston Avenue shop often doubled the sales of our other locations. The shop made a profit its very first day and never slid backward. Within a matter of months Pete and I knew that Boston Avenue was a turning point in the development of our business. Without it, our company might not have succeeded because our earning stream was tenuous, and we may not have survived many more winters. Until we rented this shop, our mix of locations was not really profitable, and it was getting old making money in the summer only to lose it in the winter. But now, with Boston Avenue on-stream we had some stability and we could weather the tough times. We probably could have kept this one location and closed the others and made as much money as with the five. However, the goal of thirty-two restaurants was important, so we kept them all. As proof of the staying power of the Boston Avenue location, after thirty years it still exists. After we began franchising, Pete and I sold it to one of our employees, Rosa Perillo, who for many years continued to benefit from its bustling location.

Rapid Expansion

After we started Subway in 1965, I devoted most of my time to the business. However, I didn’t really think of myself and the business as companions for the long term. I attended classes, I studied, and while no one would have called me a party animal, I had fun. I joined a fraternity, I dated Liz, and I had a good time in college. As important as the business was to me, I always thought of it as a means to an end, and nothing more. It wasn’t a lifelong commitment, and it wasn’t intended to support me forever. It existed to get me though college. I didn’t expect the business to end after I graduated, but I didn’t think that far ahead, either. I was committed to opening thirty-two restaurants in ten years, but that didn’t mean I couldn’t do something else simultaneously. I liked dual roles. Once I graduated from college, I assumed I would pursue my real career, and like Pete, I’d also be involved in the business. I didn’t view a profession and the business as mutually exclusive. However, through the mid- to late 1960s, I was a college student first and foremost. My mission was to go to school and graduate with a degree. Only one thing had changed since I started pursuing my mission. I no longer planned to be a medical doctor.

By my junior year I changed my mind about premed when I discovered that I didn’t like laboratory classes. They required much too much detail over a lengthy period of time, and my mind didn’t work that way. I thrived on a variety of stimuli and skills. Like a kid with a huge toy box, I wanted to play with several things at once, but only for short periods of time. I liked choosing a topic, studying it for as long as I was interested, then putting it down and moving on to something new. If I had to, I could concentrate on the same project for half a day, but that wasn’t my style. So by 1968 I switched my major from premed to psychology. Actually, I didn’t want to be a psychologist, either, but that department was willing to accept all of my science credits, and that was important because I didn’t want to take additional course work. All I wanted to do was graduate! Then I would figure out my true profession.

Deciding to Franchise

Meanwhile, I concentrated on expanding Subway. After eight years in business we had opened only sixteen restaurants, and it wasn’t likely that we could double that number to hit our goal within two years. In fact, we were certain it wouldn’t happen and our only hope of hitting the goal was to find a strategy other than opening our own restaurants. We didn’t have the money to expand any faster than at our current rate and we didn’t have the management skill to run locations well at a great distance. Plus, the more restaurants we added, the more challenging it became to manage them all.

One Monday night in 1974, rather than meeting at World Headquarters, Pete and I met in the office of attorney Mario Rubano where we wanted to discuss the future of our business. Mario was a family friend who occasionally handled some legal work for us. As we evaluated our options we talked about franchising, particularly because McDonald’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken were opening a lot of franchised units in the Bridgeport area at that time. As we left Mario’s office, we agreed to think further about franchising.

We knew nothing about the topic although we had discussed it previously. A couple of years back my uncle John DeLuca asked if he could buy a Subway franchise to open in New York. After thinking it through we turned him down, explaining we didn’t think franchising was for us. He went to another small submarine sandwich chain, bought a franchise from them, and then sold it a couple of years later when he realized he didn’t like the fast food business.

We thought franchising was for bigger companies that built free-standing units, like McDonald’s, so we didn’t think it made sense for our little take-out business. At the time we did not include tables or booths in the shops. So the first couple of times we discussed franchising, we rejected it without much more consideration than that. However, now, because we were behind schedule, we were willing to look into it again.

One Monday night, after weighing the pros and cons, we decided that franchising was the best way to get from sixteen to thirty-two restaurants. We could recruit people who would invest their money and use our management system to open and run Subway franchisees in their neighborhoods. Maybe franchising wasn’t just for big companies, we told ourselves. Maybe little companies could franchise, too. What we didn’t know at the time was that there were many other small businesses that used franchising as a method of expansion.

Rather than go out and hire consultants and lawyers to prepare us for franchising I figured that the simplest way to get started was to find a franchisee. That’s when I spoke to my friend Brian Dixon. Our wives both worked as nurses at the West Haven Veterans Hospital. Occasionally we got together to play cards or go to a hockey game, and I knew Brian wasn’t happy with his job and I thought Brian would do a terrific job with one of our restaurant.

One night between periods at a hockey game in New Haven I made Brian an offer he couldn’t refuse. I told Brian about our franchising plans and offered to loan him the money to buy our Wallingford, Connecticut location. I even said that if he didn’t like the business for any reason he could return the store to us and not owe us a penny.

He refused! Even though he didn’t like his job, he explained that he got paid every Thursday and he didn’t want to risk going into business. On several other occasions I tested Brian’s interest in becoming our first franchisee and he repeatedly turned me down. So I continued to devote my time to managing our existing restaurants and decided to worry later about franchising. Expansion would have to take care of itself.

But then one day Brian changed his mind—later you’ll read how it happened—and after he did, we changed Subway. We rented office space, hired my aunt Lucy DeLuca as our first secretary, set up shop as a franchisor, and began advertising our opportunity in the classified sections of newspapers throughout Connecticut. We set our franchise fee at $1,000—that was the amount of money a franchisee would pay for the use of our name and management systems, as well as initial training—and our ongoing royalty at 8 percent of the restaurant’s sales. Leasing space, buying equipment and supplies, signage, inventory, and other site-specific components required an additional investment.

Since Subway was already well known in Connecticut, the response to our tiny ads was immediate and steady, and the sales process was straightforward. People called us, I provided them with information, and if they were interested we met personally. Within a few months we sold franchises in Danbury, Middletown, and Waterbury. That first year, we didn’t advertise outside Connecticut and we didn’t open restaurants outside the state because our new franchisees had the fear that people were different out there!

Going Beyond Connecticut

However, we quickly broke through the boundary barrier when my wife’s brother, Marty Adomat, graduated from college and decided to open a Subway shop in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1975. Almost simultaneous to his decision, my aunt and uncle, Tony and Louise Scotti, opened a Subway shops in Staten Island, New York. Both locations were ninety minutes from our office, still a manageable distance for our fledgling franchise operation.

But then, in 1976, Aunt Louise introduced us to Jerry Smith, who was a customer in her restaurant. He and his brother, Jim, wanted to open Subway Restaurants in Baltimore, Maryland, where they had grown up and where Jim still resided. Baltimore was a four-hour drive, and I thought it would be difficult to provide adequate service to a franchisee so far away. By this time, I had learned that frequent communication and guidance was an important element of franchising. Also, I knew that as we franchised further from home it would be more difficult to service the locations, just as it was more difficult to operate company-owned restaurants that were far away from our home base. In addition, I was concerned that the Baltimore unit would be all by itself in a big city and until we could sell additional restaurants in the area, and have someone nearby to service those restaurants, it didn’t make economic sense to expand to Baltimore.

But then I considered another approach. I told Jim that we would agree to sell him and his brother a franchise, but to do so we would need someone locally to take on more responsibility. I suggested that Jim should be that person, and I said if he was willing to do so, we could work out a deal. Jim was willing and it took only a day or two for us to work out the details. That’s when we created the position of Development Agent, a person who would help us build and service restaurants in a specific territory. Jim liked the idea, and that’s how we planted Subway’s flag in Baltimore.

Right after we developed this new servicing concept the Scottis became Development Agents in New York and my brother-in-law, Marty, became a Development Agent in Springfield, Massachusetts. Later, Brian Dixon became a Development Agent for Rhode Island and New London County, Connecticut. These pioneers are still Development Agents and Subway owners today.

.. During one family vacation in Florida Marty and his wife, Lasha, told me they no longer wanted to live in the Snowbelt so we talked about Subway opportunities in other parts of the country. Houston sounded interesting to them, so on the ride back home from Florida they turned left to check it out. Soon thereafter Marty traded his territory in Massachusetts for Houston, Texas and due to the size of that city, he teamed up with a partner, Bill Horner. Marty, has since retired as a DA but serves as a mentor for our Development Agents in Germany and is still involved in the Subway business.

Setting Another Big Goal

As we celebrated Subway’s tenth anniversary in 1975, the fact that we were several restaurants shy of our goal wasn’t much of a disappointment. We knew it was only a matter of time until we would surpass that goal and set a new one. We opened our thirty-second restaurant in 1976; in two more years we opened our 100th restaurant; and by 1982 we doubled our network to 200 units. The rapid growth created numerous challenges that required the resolve of our talented home office team. Subway was no longer a tiny operation. It was on track to expand far greater and faster than Pete and I could imagine.

So now what do we do? How were we doing? Was 200 restaurants a lot or a little? What else was possible? If we set another goal, what would it be? After conducting a market study of the fast food industry in 1982, sizing up other chains and their growth, and considering Subway’s growth, I decided our new goal would be 5,000 restaurants by 1994. It was an aggressive goal. Most of our employees were stunned when I announced it, and some of them thought I was absolutely crazy. We only have 200 restaurants. How are we going to open up 4,800 more?

From the perspective of many of our team members it seemed impossible to grow Subway twenty-five-fold! But from my perspective it looked like an extremely challenging objective, but not much more challenging than opening thirty-two restaurants in ten years from an investment of only $1,000.

After all, we had already spent nine years learning how to run our company restaurants, and another eight years refining our franchise organization. We had developed terrific control systems, we had a network of experienced franchisees, and we were beginning to put Development Agents in place around the country. We had seventeen years of experience to rely on, and to my way of thinking, we were going to keep doing what we were already doing, but we would just do lots more of it.

There was no doubt in my mind that if we worked hard and did lots of things correctly the goal was achievable. Despite any misgivings about the goal, everyone on the team focused on the objective. We made further improvements to Subway and by 1991, a full three years early, we surpassed the 5,000-restaurant goal!

We were growing so quickly that by that time I had already revised our goal to 8,000 restaurants by 1995 and we even surpassed that goal two years ahead of schedule. In fact, in the ten-year span between 1988 and 1997 we added over 10,000 locations to Subway, and for most years during that period we held the distinction of being the world’s fastest-growing franchise company.

How did we expand so quickly? What most people don’t know is that our existing franchisees who were in an expansion mode opened about 70percent of our new restaurants each year. We have many talented, ambitious, hardworking franchisees in Subway and they fueled our spectacular growth. Once they learned the details of the business and how to succeed with a single unit, many would return to invest in additional restaurants. Having succeeded once with Subway, they wanted to succeed over and over again. Even to this day, about 70 percent of our new franchises are sold each year to existing owners who are reinvesting in the business. By keeping the operation simple, the investment in our restaurants low, and by discounting the initial fee for existing franchisees who are expanding, we made it desirable for our franchise owners to open multiple units.

When we passed the 8,000-store mark we decided it was time to publish a different type of goal. Now, rather than measuring how many restaurants we opened, we decided to concentrate on cents per capita in North America. Our goal was for every man, woman, and child to spend 50 cents per week at Subway by 2005. We still have a way to go to hit that mark, but we’re up for the challenge.

International Expansion

In terms of store counts we now have to think of expansion on a global scale. As we approach our40,,000th restaurant——it looks to me like a large fast food company will be able to operate more than 100,000 outlets worldwide by 2050. I’m fairly confident McDonald’s will be first to hit that number, but we haven’t as of yet set a worldwide restaurant count goal. Right now we’re working on our international infrastructure and if we continue to do a really good job we might be able to reach 100,000 outlets, too.

Where will we open all of those Subway shops? Outside North America, for the most part. We’ve operated in international markets since 1983 when we opened a small store in Bahrain, in the Persian Gulf. Shortly thereafter we had a false start in the U.K., and in 1986 we opened in Canada. Today, we are the world’s largest restaurant chain with more locations than McDonald’s. We’ve been making strides on the international scene, thanks in part to the persistence of Don Fertman, who heads up our global development division. Today we have more than 11,200restaurants outside the U.S., But there’s still lots of work to do.

Even though we’re now located in 100countries and in most every region of the world, including countries like Japan, the United Kingdom, Australia, Venezuela, South Africa, Israel, and China, in most places we only have a small presence. Actually, Subway today feels a lot more like 1982 when we had only 200 restaurants scattered across the U.S. We’ve got a good start but there’s still a lot of growth to look forward to.

Our international plan is to follow the same basic formula that has worked so well for us in the U.S. We’re looking for dedicated franchisees to operate in their neighborhoods, and just as we did when we expanded to Baltimore, we’re looking for Development Agents to lead the expansion in local markets around the world.

While our terrific team has accomplished a lot in the past forty seven years, there is still much work and many challenges ahead. Today we must put the pieces in place for Subway to become an international powerhouse. But like every big objective that we’ve faced in the development of Subway—many of which you’ll read about in this book—our team is up for the challenge.

What I never expected, and what Pete Buck never expected, was that we would build such a large company from such humble beginnings. For two guys who knew almost nothing about business, the food industry, and franchising, our forty seven-year-old partnership has led to our personal success as microentrepreneurs. More significantly, we’ve touched, and in many instances changed, the lives of people worldwide. For a kid from “The Projects,” it’s been a fabulous journey. I hasten to add that these accomplishments have less to do with me, and Pete, than they do with our associates at our regional offices around the world, our CT based team at Subway World Headquarters, our Development Agents, and most importantly, our incredible franchisees. These are the folks who continue to make the journey exciting and rewarding.

Come along now, and I’ll explain each of the Fifteen Key Lessons in more detail, and I’ll introduce you to twenty-one other microentrepreneurs whose own incredible stories emphasize the value of these lessons.