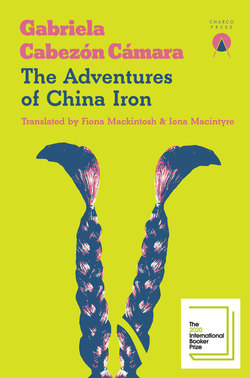

Читать книгу The Adventures of China Iron - Gabriela Cabezón Cámara - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеUnder the British Empire

One rainy dawn I put on my first ever raincoat. ‘The subjects of the British Empire have appropriate etiquette for all occasions’, Liz explained, outlining their manners and mountain ranges, their climates, deserts and forests. The details of all the clothing in the Empire built the world for me, a world that was round not flat. I’d never thought about it till then, my world map hardly stretched beyond the pampas and a few vague notions: Indian Territory, Buenos Aires, a watery abyss and then Europe, with Spain at the bottom and up there the British Isles, the cradle of men and weapons. This ball-shaped world came to life through Liz’s stories, half in Spanish, half in English. She started populating it with sacred cows, soft saris, hot Indian curry, African tribesmen with painted faces, elephants with tusks the length of a small tree, huge eggs laid by ostriches, the larger cousins of our ñandús, Chinese paddy fields, curly-roofed pagodas and coolie hats pointing up to the sky. As we travelled I began to understand some of these things, but the rest I understood much later, over the course of all the time we spent together. I found it hard to reconcile myself to the idea that we were on the bottom half of a globe when we seemed to be on the top, but no, Liz was sure that Great Britain was on top. How could that be? It was quite plain that your feet were on the ground wherever you were, even in the land of pygmies, gorillas and diamonds (hard transparent stones that are wrenched from deep inside rocks). She insisted that on top was Great Britain, the land where machines moved by themselves with burning wood as though movement was a huge bonfire, or as if the pieces of burning wood were horses. Or oxen, like ours, the four strong, docile oxen who pulled the wagon which enfolded me just like the silk petticoat and the awning proofed with wax that at the end of the day was just tallow from a cow, though it had previously been filtered many times through sandalwood and smelled like a heady flower, like a laudanum flower, I mean, like a drug, just like opium must smell. Opium was like caña but much stronger than our drink, she explained to me, and so many people succumbed to it in the North African heat, where men swathe their heads in a few metres of cloth for a hat, and women are covered from head to toe. The raincoat with its eastern smells covered me. The wagon, waxed like the raincoat and smelling the same, covered us. All three of us – not just me, but Estreya, who travelled on Liz’s lap to begin with, while I took the reins, and Liz herself. It was like we were secreting fine threads to make a shell or carapace, woven together like a kind of house made not from spider’s silk, straw, mud or the leathery shell of a crab, but gradually formed from the loops of words and gestures. From Liz’s story and my care for each of our possessions, a space was emerging. One that was ours, with the wagon which went steadily forward, with that empty land which was becoming as flat as it seems to those who have known hills and mountains. The vastness of the pampas was becoming flatter to me with every new tale of bustling London’s smoky sprawl; the desert horizon widened against a backdrop of African jungles; the prickly grass, the waving grass and the scrubby bushes became squat in contrast to the forests of Europe; these rivers without banks paled against her English rivers flanked by red-brick houses, so very different to our rivers bordered by mud and with nothing around but reeds, rushes, herons and flamingos, Liz’s favourites – luckily she likes the strong colours of the pampas. She said that everything there was shades of brown against the endlessly pale and transparent blue of the sky, except when the dust rose, or when different hues of green appeared, the young wheat springing green and glorious after summer rain, only matched, we thought then, by the green and pleasant fields of England.

You only get the other colours in the sky at dawn or dusk, or in the flamingos who are always colourful. It was raining again and light was reflected on all living things, and on the dead, just the odd cow bone at that stage. The earth was burnished copper and our protective shell was growing around us, keeping the three of us warm. We were sustained by Liz’s words, Estreya’s pink tongue, and my rapture at being there, calm as a well-fed animal in the sun.

Calm, but slightly confused: according to Liz, the earth was a round ball, and we were at the bottom. Maybe there was something about a stone in the North that pulled everything towards it, above Great Britain, because there was something above England, above everything, Liz explained, where the planet’s hat would be if the planet was a head, a head without a neck. What, with its head chopped off? No, just a round head without a body. Just a head, did I understand? No I didn’t; I’d never seen a head without a body. No, of course not, it was just an example. An example, she explained to me, was something you said to make an idea clear. But you don’t get heads without bodies, I insisted, so what can it be an example of, if it doesn’t exist? An example of things that don’t exist, but you’re right, she said, and she went back to talking about the planet, and this time she used the example of a little orange, which made it much easier for me to imagine: it clearly has a top, where the stalk connects it to the tree, and a bottom. And which tree does the earth hang from? It doesn’t. So the orange didn’t help me much either. Anyhow, I began thinking that on the top half of the planet, not just in England, things grew upwards more easily. Apparently there were hills and mountains and it was full of tall trees as high as several men on top of each other. How many men? The highest trees would be ten or fifteen men high. Do they look like ombús? A bit, but the trees there are taller than they are wide, elongated; the ombú is squat, as if gravity was stronger in the bottom half of the planet and everything was flattened or forced underground. Gravity was what made things fall down. So how come it didn’t squash us all – me, Liz, Estreya, the wagon, the oxen, mules, cows and horses?

That night, Liz made a stew out of an armadillo that I’d caught and butchered. She cooked the poor creature in its own shell. She added ingredients that I was beginning to recognise; a mixture of onion, garlic and ginger with cloves, cinnamon, cardamom, chilli pepper, peppercorns, cumin and mustard seeds. Everything bubbled away in the shell, and when it was done, Estreya and I had our first taste of spicy food. Everything we were experiencing was new to us; ideas, sensations and even our taste buds were expanding under the British Empire.