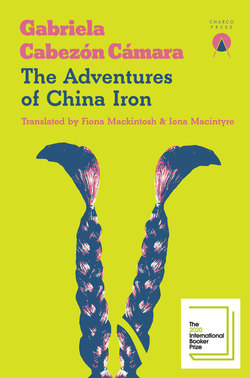

Читать книгу The Adventures of China Iron - Gabriela Cabezón Cámara - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLa China Isn’t a Name

As soon as we came to a riverbank, the Gringa brought the oxen, horses and wagon to a halt and smiled at us both. Estreya scampered round her, wagging his whole body, dancing for sheer joy and delight. Elizabeth smiled at us as she went into the wagon. I was still waiting for her permission to be allowed in, but she didn’t let me, she came straight out again with soap and a brush, and still smiling and making friendly gestures, she took my scrappy clothes off as well as her own, grabbed Estreya and plunged us both into the river, which wasn’t as muddy brown as the one other river I knew. She washed herself, her fair freckly skin, ginger pubis, pink nipples, she looked like a heron, a ghost made flesh. She rubbed my head with soap, making my eyes sting. I laughed, we both did. I gave Estreya a good wash too, and once we were clean we carried on splashing about in the water. Liz got out first, wrapped me in a white towel, brushed my hair, put me in a petticoat and dress and then, when that was all done, she came back with a mirror, and there I was inside. I’d never seen myself except reflected in the mostly calm water of the lake, where my reflection was crisscrossed with fish, reeds and crabs. I saw myself looking like her, a señorita, little lady, Liz said, and I started behaving like one, and although I never rode side-saddle and soon would be using the baggy gaucho trousers the Gringo had left in the wagon, that day I became a lady for ever, even when riding bareback like an Indian and slitting a cow’s throat with one slash of a gaucho knife.

We also sorted out the issue of names – it was an afternoon for baptising things. ‘Me Elizabeth’, she kept repeating and eventually I learnt to say it: Elizabeth, Liz, Ellie, Elizabeta, Elisa. ‘Liz’, she said firmly, and that’s how it was. ‘What you name?’ she asked me in the broken Spanish she spoke back then. ‘La China’, I answered. ‘That’s not a name’, Liz said. ‘China’, I insisted, and I was right, that’s what La Negra used to shout at me, La Negra who would later be widowed by my good-for-nothing husband. China is what he’d call me last thing at night as he dropped off to sleep, ‘safe and sound in the arms of love’ as he put it later in one of his songs. He also shouted China when he wanted his food or his trousers or mate to drink or anything else. I was La China. Liz told me that where I was from, all women were called chinas but they each had their own name as well. Not me. At that point I didn’t understand why she got so upset, why her little pale blue eyes started to fill up. ‘We can do something about that’, she said – I don’t know which language she said it in, nor how I understood her – and she started pacing up and down with Estreya jumping at her feet. ‘How would you like to be called Josefina?’ she said, turning to look directly at me. I liked the name: La China Josefina couldn’t be keener, La China Josefina’s hands are cleaner, La China Josefina’s figure is leaner, La China Josefina has a serene demeanour. La China Josefina was good. China Josephine Iron, she named me, deciding that for want of another surname, I’d better use the one belonging to my no-good husband. I said I’d like to take Estreya’s name too, so I’d be China Josephine Star Iron. She kissed me lightly on the cheek, I hugged her, then I set about the none-too-easy task of getting a fire going and cooking some meat without singeing or spoiling my nice dress, which I managed. That night I slept inside the wagon, which was much more of a home than my old shack. The wagon had whisky, a wardrobe, hocks of ham, biscuits, a shelf of books, bacon, oil lamps… Liz taught me the name of each thing. And best of all, at least by the standards of a young woman on her own, two shotguns and three full boxes of gun cartridges.

I hugged Estreya tight as he curled up with Liz, plunging myself into their newly-washed, floral smell. I wrapped myself in those lavender-scented sheets, only later figuring out that the smell wasn’t a quality of the cloth the way the texture was, that smoothness which enveloped me that night and all the nights of what would be – broadly speaking and dividing things rather dramatically – the rest of my life. Among those perfumed sheets I felt Liz’s breath, smooth and spiced, and I just wanted to stay there, immerse myself in her breath, though I didn’t quite know how. I slept, peaceful and happy, snug amongst perfumes, bedclothes, dog hair, red hair and the shotgun.