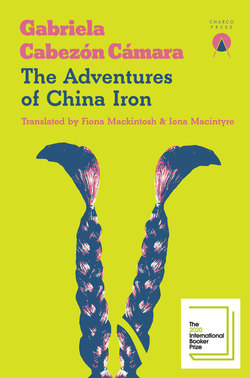

Читать книгу The Adventures of China Iron - Gabriela Cabezón Cámara - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBy Dint of Force

Liz carried on with her stories about Great Britain. When she went to London, the sky was leaden and smoky from the locomotives and factories, and the almost incessant rain had a sharp tang to it. The air she breathed was damp and grey, with a strange orangey tint, and so heavy and thick that she could almost see it. Yet as soon as she left the city behind, the light gleamed on unbroken fields of grass that stretched all the way to cliffs pounded by the sea. The land ends abruptly there, as if England had been cut off from the rest of the world with an axe, as if the land had been forcibly condemned to an insularity which those of us who live there, we, the British, darling, try to overcome by dint of force, making ourselves the centre, organising the world around us, being the motor, market and matrix of all nations. Here in Argentina we’re so far removed from that other island which rises up sustained by its weaponry, its steamships, its machines invented to dominate the world with ever faster production. That island where metal goods reign as intractably as the railroads laid down all over by royal decree so that the fruits of men’s labour migrates from fields, mountains and jungles to ports, ships and finally into her own port, to the all-devouring mouth of Kronos. That mouth where everything becomes fuel for its own insatiable speed: from the still-warm hairs on a cowhide to the frozen facets of diamonds, from stretchy rubber to crumbling coal. The power of Great Britain isn’t in armies or banks: our strength comes from speed, beating the clock, trailblazing, cutting production times, faster ships, machine guns, banking transactions made in a matter of days, above all the power of the railways dividing the earth, heading for every port laden with imperial manufacturing and returning with spoils and fruits from every land.

Everything was still possible in that languid time of the pampas, during our chats over Rosario’s asados. He was constantly amused at the sound of English; ‘what’s your word for that, señora?’ he’d ask Liz, and explode with laughter whenever she answered ‘cow’, ‘sky’, ‘horse’, ‘fire’ or ‘Indians’, scattering the birds who were picking ticks off the runaway cows. He would merrily gnaw at a rack of ribs and – in gaucho fashion – wash it all down with caña. Then over pudding he’d start talking to his horses. He was sorry, he said, but the horses couldn’t go travelling with Liz because where she came from, wagons moved by themselves. ‘Wheels move with rods over there, you poor horses would be out of a job! You’d be up shit creek! You’ll just have to stay here with me; where the Gringa comes from, they don’t need the likes of you,’ and he’d pat them fondly. We laughed too and Estreya ate out of his hand and curled up in Rosario’s lap as if he was still just a puppy. Liz sent Rosario off to bed and he did as any gaucho would: he took his poncho and the sheepskin off his saddle and lay down with the animals. He’d taken a shine to Estreya and together they slept out under the stars with Braulio.

We went, just the two of us, into the warm, yellowish fug of the wagon. Liz snuffed out the candles, stripped me of the Gringo’s clothes, wiped me down with a damp sponge, dried me, put a petticoat on me, lay down in my arms and went to sleep, as if she hadn’t noticed the goose bumps all down my body, nor caught the urgent smell of desire that hung in droplets from the hairs of my pubis until they spread slowly and languorously down my thighs.