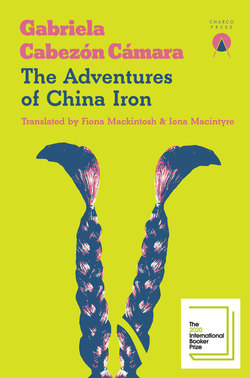

Читать книгу The Adventures of China Iron - Gabriela Cabezón Cámara - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThat’s Also Something You Eat and Drink with Scones

The desert framed the scene, a brownish plain, the same in all directions, a flat surface on which the sky balanced like there was nothing else in the world. You might say that being there, on the wagon box or riding my horse, was living the life of a bird, a bit like flying, your whole body submerged in the air. It doesn’t seem right, there are hardly any birds in the pampas and the few we have are low-flying or can’t fly at all. You get flamingos like clouds of shrill pink on the horizon. You get ñandús that run faster than horses, their strong elastic legs scything the ground and raising the dust. The ñandús connect pampa and sky. And, like at sea, where you know you’re approaching dry land because you start seeing birds overhead, the same happens in the desert with water and groups of people: birds also circle villages and encampments. So being in the pampa was like soaring over a scene with no adventures but its own, its shifting skies and our journeying. Over the dark line of the horizon the sun and the air ravel and unravel. When it’s clear, the sun and air are scattered through a prism at different times of day, cut at dawn into reds, purples, oranges and yellows that turn gold as they hit the ground, where the little green takes on a tender and brilliant texture and everything upright casts long soft shadows. Then the sun crushes it all until the prism comes back. And the night in summertime is dark purple and shot through with stars. All that time I had the soles of my feet and my shadow on the ground and the rest of my body up in the sky. You might say that’s the same everywhere. But no, back there in my pampa, life is life in the air. Even celestial, sometimes; far from the shack that had been my home, the world was paradise. I can’t remember having experienced that before, that total immersion in the endlessly shifting light. I felt the light inside me, felt I was little more than a restless mass of flashes and sparks. Quite possibly I was right about that.

There wasn’t much shade for me beyond the sweet-smelling wagon, the only space that seemed more a part of the earth than the sky even though it was a good few feet above the ground. Home always seems fixed to the ground, even when home is a boat. Or a wagon. And that was my first island, the island that took shape for me as we made our journey, a rectangle of wood and canvas that we kept dark and cool to discourage the flies that seemed to come from nowhere and multiply effortlessly. Of course there were carcasses around and we added even more bones to the world every time we slaughtered one of the hundreds of cows following us. We didn’t kill many: they’re big animals and once we’d butchered one we would cure it making a delicious jerky that Liz had perfected. First she’d plunge the fillets into salt and then steep them in curry and honey. When she reckoned they were ready she’d put them on the fire for a while: they crunched in your mouth, melted salty-sweet and spicy on your tongue, then burned down to your stomach. We didn’t even do that at the settlement. We would slaughter a whole cow, eat what was necessary, and then the rest was for the caranchos. Fierro used to say that the caranchos had to eat too, and I tend to think he was right about that, although he didn’t take into consideration the huge number of carcasses that our country produced, and not just dead cows; Indian and gaucho corpses also fed several generations of scavenger birds. But going back to my life in the air and my home in the bobbing wagon, like I said, we kept it dark and fresh, and as full of nice smells as an East India Company warehouse. The smell of near-black tea leaves torn from the green mountains of India that would travel to Britain without losing their moisture, and without losing the sharp perfume born of the tears Buddha shed for the world’s suffering, suffering that also travels in tea: we drink green mountains and rain, and we also drink what the Queen drinks. We drink the Queen, we drink work, and we drink the broken back of the man bent double as he cuts the leaves, and the broken back of the man carrying them. Thanks to steam power, we no longer drink the lash of the whip on the oarsmen’s backs. But we do drink choking coal miners. And that’s the way of the world: everything alive lives off the death of someone or something else. Because nothing comes from nothing, Liz explained that to me: everything comes from work; that’s also something you eat and drink with scones. Liz would sometimes bake scones in the ovens that I made by digging a pit in the earth. The harder you work, the better it tastes, she declared. I said yes to her, over those months we spent together in the enormous sky of the pampa, I always agreed with her. I could have contradicted her quite easily just by pointing out her delight at asado, something that doesn’t really take a lot of work. I didn’t though, I didn’t contradict her. Back then I thought about it and thought I was being clever. At some point, and I hadn’t even said anything – that was how transparent the distance was between us – she answered that asado doesn’t require much human effort, but you did need an animal to suffer. She said that even Christ, Our Lord, was made flesh in order to be sacrificed: he had worked for the eternal salvation of all of us, and there has never been a world or a life that wasn’t both fuel and flame. And there never would be.