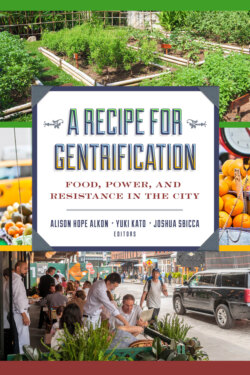

Читать книгу A Recipe for Gentrification - Группа авторов - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 The Taste of Gentrification

ОглавлениеDifference and Exclusion on San Diego’s Urban Food Frontier

PASCALE JOASSART-MARCELLI AND FERNANDO J. BOSCO

The crowd, hipster. The decor, artsy. The peeps, gangsta. The food, legit. I dig this place.

The food is good but the experience is ridiculous! These are tacos for goodness sake […] This place is a joke. […] I wish I could turn back time and drive down to Ed Fernandez or Gordo’s or any other taco shop in the county for that matter.

—Yelp reviews of ¡Salud! in Barrio Logan, San Diego1

In a context where culture has become a key determinant of the economic success of cities, food and taste have emerged as symbols of neighborhood transformation and powerful tools of urban renewal. According to Bourdieu (1984), taste reflects identities, reveals differences, and reinforces class positions. Similarly, food distinguishes places, giving some neighborhoods character and value, while stigmatizing others as food deserts or food swamps, characterized respectively by the absence of healthy food or the abundance of so-called junk food (Joassart-Marcelli and Bosco 2018a). In contested places, debates about food and taste—including those taking place online on social media platforms like Yelp—reflect changing cultural aesthetics and social dynamics and illustrate ongoing processes of spatial exclusion.

In gentrifying neighborhoods, farmers’ markets, community gardens, cosmopolitan restaurants, microbreweries, and authentic eateries have gained popularity and often play an important role in branding locales and attracting people from other places (Joassart-Marcelli and Bosco 2018b). Unlike upscale restaurants and high-end stores, these contemporary food projects appear to embrace a multicultural and democratic ethos that seemingly values diversity and community. Social media posts about those spaces, including Yelp reviews, both reflect and reinforce these ideas, with terms such as “authentic,” “legit,” and “the real thing” used liberally to describe the food and dining experience. Urban elites, including developers, local politicians, and financiers, encourage and capitalize on these cultural narratives and symbolic assets in order to promote specific neighborhoods.

At the same time, however, food insecurity remains a significant concern especially among lower-income residents, who have lived in these neighborhoods and patronized local food stores and restaurants for a long time. Although these residents may welcome some changes in their foodscape, particularly those that improve access to affordable, healthy, and culturally appropriate food, evidence suggests that they feel excluded from the new developments and experience them with ambivalence, if not resentment (Joassart-Marcelli and Bosco 2020). Their apprehension over current changes in their neighborhood’s food scene is also reflected on social media where fears of gentrification and lost sense of place are commonly expressed. Persistent economic hardships and social tensions put into question the democratic and cosmopolitan posture that the majority of new businesses adopt.

Taste then becomes a way for newcomers and longer-term residents to relate to each other and to place. As discussed in chapters 2, 3, and 5 of this volume, these encounters may forge connections, but they may also exacerbate difference rooted in broader socio-spatial processes associated with class, race, and ethnicity that shape cultural understandings of “good food.” New food businesses take a particularly active part in both reflecting and molding taste and shaping the social and cultural character of place. The type of food they sell, the way they present themselves, the values they seem to support, and the aesthetics they embrace are all central in producing a foodscape that is more or less inclusionary.

In this chapter, we intersect literature on gentrification with research on taste and food to investigate how taste and place relate to each other in ways that reproduce social distinctions based on class, race, and other factors. In particular, we explore how new food spaces and practices are represented and promoted in Barrio Logan and North Park—two urban neighborhoods of San Diego that are characterized by different stages of gentrification. Our goal is to highlight the role of taste, as a social, cultural, and emotional construct, in contributing to gentrification and displacement—what we call the taste of gentrification.

We begin with a review of theoretical research on the social construction of taste, including Bourdieu’s work, and argue for the benefit of inflecting this scholarship with a place perspective. Next, we turn to debates within the gentrification literature and discuss the significance of food and taste in reconciling theoretical differences between political-economic and cultural approaches. Using mixed methods, we then combine mapping with analysis of qualitative data from various media sources, including social media and local food publications and news outlets, to explore the key elements of the taste of gentrification, as well as how and where it is produced.