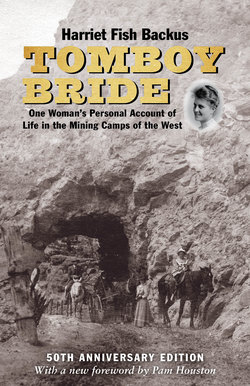

Читать книгу Tomboy Bride, 50th Anniversary Edition - Harriet Fish Backus - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

I was late for my wedding—so late that the date on three hundred engraved announcements had to be forever wrong. When my sweetheart of high school days telegraphed from Telluride, Colorado, saying he had found a position as assayer at the Japan Flora Mine, he asked me to meet him in Denver to be married. This caused considerable consternation in my family.

“Hattie, I don’t think you should go alone,” said my father with a worried look. “Young girls like you don’t travel by themselves.”

“I’m not afraid of her traveling alone,” said my mother, “but it wouldn’t be proper for her to be unchaperoned in Denver.”

Working for the Telegraph Company after the San Francisco earthquake, preceded by two years of teaching school, had not conditioned me for “wild adventuring.” But since George could not leave a new position for the trip to California, I must go to him.

A graduate from the University of California School of Mines, George had been on guard duty in San Francisco after the earthquake and fire of 1906 which closed the schools. Released from that, he went to Colorado looking for work. Now he was ready to take a wife, and, since his uncle had arrived in Denver, my parents finally consented to our marriage away from home.

“Will arrive November twentieth. Arrange for marriage that day,” I telegraphed, for that was the twenty-ninth anniversary of my mother’s and father’s marriage.

As he had suggested, I packed warm clothing, heavy blankets, linens, and a red and white tablecloth which, according to all the mining stories I had read, was indispensable, the flat silver that had been a wedding gift from my parents, and a few of my precious books. The railroad official assured me that by leaving Oakland on the eighteenth I would arrive in Denver at eleven o’clock on the morning of the twentieth.

“You’re sure there’ll be no delay?” I asked, as though he could foresee the future.

“There won’t be any heavy storms this time of year. Don’t worry. You’ll be there on time,” he assured me good naturedly.

It was a day of blue and gold, typical of Oakland in November, when my farewells were said and my big adventure began. There were few passengers and I was the only woman in the coach. The elderly conductor, seeing me alone, seemed solicitous. Late that evening we pulled into Nevada where a gold strike had aroused excitement. At the Reno depot we heard loud shouts of greetings and farewells. Into the coach swaggered a tall, bronzed miner with the air of a man who had “struck it rich.” The collar of his heavy coat was turned up to his hat brim. He stood and surveyed the passengers as if to make certain they were aware of his importance, and I turned my head to avoid his too prolonged stare.

In the morning he presented me with a rose taken from the dining car. I said, “Thank you,” and turned away. At noon I refused his invitation to be his guest at dinner. After several more rebuffs he snarled, “You and I would get along like a cat and dog.”

“Not as well,” I snapped, thinking of reporting him to the conductor.

In more amiable mood he began to coax me. “I have a sister in Denver who is meeting me at the train. Will you let us drive you around the city?”

“No. I am being met there by a gentleman,” I snapped again.

Our voices carried and a young man seated across the aisle rose and strolled to where I was and sat down beside me.

“Nevada’s an interesting state, isn’t it,” he began as if we were long acquainted.

“It certainly is,” I replied, and as we continued a conversation casually, the miner left abruptly.

“My name is Pinkerton,” said my rescuer pleasantly. “I am on my way to Ohio to be married. I saw that you were being annoyed and decided to interfere.”

“Thank you very much. Tomorrow I am to be married.” I took the card he offered and tucked it into my purse. It remains among my cherished souvenirs.

Harry Pinkerton’s calling card.

At Ogden, Utah, everything was covered with lovely, downy white as I stepped off the train for a short walk.

“My goodness,” I remarked to the conductor, “what a heavy frost.”

“That,” he replied with a superior tone, “is snow!” I had encountered the beautiful stuff in which I was to wallow for many years.

We reached Green River, Wyoming, in the evening and I was early asleep. Waking in the morning, I was aware of an ominous quiet, no chugchug of the locomotive, no clacketyclack of the coach wheels, no lonely “whoooo” of the whistle, no anything. Perhaps we had reached Cheyenne. We were due there this morning. Surely, very soon I would be in George’s arms. Yet something seemed very wrong even to my inexperienced perceptions. Dressing hurriedly I called out, “Porter, where are we?”

Unconcernedly he answered, “Green River, Ma’am. Just where we were last night, waiting for the mail from a branch line that was delayed.”

Like marbles spilled on a polished floor my plans scattered in all directions. At that moment we should have been in Cheyenne leaving for Denver. We still had four hundred miles to cover in thirteen hours, and that would have been really speeding.

Tears stung my eyes but before I dried them came faintly the call “All aboard!” and the wheels began to grind and roll. I turned to the window to hide my tear-stained face. Then I became aware that my name was being called … “Miss Harriet Fish.” The conductor handed me a telegram which I feverishly tore open. Already George was aware of the delay.

“Under the circumstances are you willing to go directly to the minister?” he had wired. I wrote my reply on a telegram blank, “Yes, it must be tonight.” I begged the conductor to send my message as soon as he possibly could.

That day I received three telegrams from George. The Reverend Dr. Coyle would wait for us and perform the ceremony. At seven we reached Cheyenne and boarded a special two-coach train waiting to run us to Denver. Barring another delay we would be there in four hours. But after a steady run of thirty minutes, we pulled on to a siding and stopped! I hunted for a conductor and abruptly asked, “What now?”

“We are waiting to give the right of way to the regular northbound train due through here any minute,” he explained.

One hour later it whizzed by. That delay determined the date of our wedding. At one in the morning I stepped off the train for George’s eager greeting. Together at last, our hearts pounding with happiness, we hugged each other tightly, the strain of the unpredictable trip momentarily forgotten. From the depot we drove to the Hotel Savoy where the bridal suite had been reserved. To this I retired a very exhausted and lonely bride-to-be, while George joined his friend, and best-man-to-be for the night.

Next morning he hurried to the jeweler to have the date corrected in the wedding ring, arrange for the ceremony, and order dinner sent up to our suite. Meanwhile, I spent the time laying out my wedding clothes.

My new corsets were too tight and the lacings had to be loosened. The silk feather-stitching of my long flannel petticoat recalled to mind my mother’s patient needlework on my simple trousseau, consisting of three of everything. The white petticoat had three ruffles and I made certain the button on the waistband was secure. A white corset cover with eyelet embroidery and white drawers with ruffles were carefully smoothed free of suitcase wrinkles. Black lisle stockings were more expensive than the customary cotton ones, but recklessly I had purchased three pairs to wear with my shiny patent leather shoes accented by pearl gray buttons.

The engraved marriage announcement card. Because of a train delay, the announcement has the wrong date.

Mother had packed my wedding suit with tissue paper, and while unfolding it my hands trembled. It had cost such a big share of money saved from my school teacher wages of sixty dollars a month. I smoothed the satin-like reseda broadcloth, and the lovely jacket trimmed with gold and green passementerie that, once glimpsed, had become irresistible.

By my watch, time was flying, so I began dressing. Three times I coiled my hair and pinned it on the top of my head before being satisfied. George had often said it was my two long braids of hair that first won his heart on a well-remembered day in high school. The blouse of ecru net fluffed out of the front of my jacket. Petticoats and skirt were ankle length and correct according to Armand Calleau of the exclusive San Francisco shop where I bought my suit.

From a hat box came my crowning glory. Oh, that hat! White felt with a turned-up brim faced with black velvet and topped with a curving white ostrich plume, the ultimate in style. No bride, ever before, was so proud of her bridal outfit.

Smoothing on the fingers of my gloves I gazed into the mirror hoping George would be pleased. And so he was when he arrived with the ring and a velvet box containing a gorgeous sunburst of diamonds and pearls. With shaking hands I pinned it at my breast.

“The carriage and my uncle are here,” he said.

In the manse of one of Denver’s splendid churches, George placed on my finger the wide gold band which never has been taken off, and Dr. Coyle said, “I now pronounce you man and wife.”

We stayed in Denver until Saturday night. I was so conscious now of being Mrs. George Backus that I felt as if all who saw me must be aware of it. George bought me a pair of pretty russet-colored, high-button shoes, and it was a long time before I became reconciled to his extravagance; five dollars for a pair of shoes!

“I’m not going to tell you anything about how and where we will live,” he said. “I’ll let you find out for yourself.” He smiled, as if picturing the somersault my life was to take. “But I think you should buy a cookbook for high altitudes.”

He was so right. I needed a cookbook, any kind, because I was unable to cook a meal at sea level in Oakland. For the first time he handed me some money. Into my mind marched Grandmother Fish with her stern admonitions about propriety. I had to remind myself that now I was a wife, thereby permitted to do so shocking a thing as to accept money from a man. The Rocky Mountain Cookbook became my guide, philosopher, and daily companion.

George insisted that I buy warm gloves, long tights, and “arctics.” I strenuously objected to the latter—heavy overshoes with thick rubber soles and high cloth tops fastened with buckles.

“I wouldn’t want to be seen in such things!” I protested.

“Without them your feet and shoes would be soaking wet. All the ladies wear them. Look.” Certainly I could see several well-dressed women with them on. So, reluctantly I bought a pair of the hideous things and suffered whenever I looked down at my feet, which looked gigantic to me in the arctics.

On Saturday night we left Denver, arriving the following morning in Salida where we changed to a narrow-gauge railway. There had been no dining car on either train and no time to eat at a depot restaurant. George dashed to a store and returned with a can of sardines and some stale soda crackers for our honeymoon breakfast.

Now we were rolling through the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River that opened into its lovely valley and on to Montrose. There we changed to another narrow-gauge railway. When we reached Ridgway Junction it was dark and cold. The Stub, a small dingy train, was to carry us to Telluride and proved to be a mere foretaste of what was ahead. The engine, baggage car, and dismal passenger car were relics of a past generation. We mounted two steps from the small station platform and with three additional passengers stumbled along the aisle. At each end of the car dirty oil lamps shed a smoky light on adjacent seats.

With great effort the small locomotive shuddered and jerked into motion on a narrow, shaky roadbed. Puffing and straining it climbed higher into the piedmont of the lofty San Juan mountains. The cold increased rapidly and we were thankful for a potbellied stove at one end of the car. Also, I began to appreciate my warm gloves and the arctics. Such cold was new to me.

Night had fallen when we reached Telluride, named for the ore tellurium, a silver-white metal having properties like sulphur found near gold or silver-bearing ore. Telluride was the terminus of the miniature line which entered the gulch through the only break in the surrounding mountains. We were on the floor of the canyon but walking in the darkness along the path to the only hotel we could feel the precipitous walls closing us in. The Sheridan, a plain brick structure which had seen turbulence and mob violence, was quiet. A lonely clerk sat behind a desk in the bare lobby, dismal and dimly lighted. As I climbed the stairs a tugging sensation in my chest was a reminder that we had risen in the world 8,765 feet.

Our cheerless hotel room contained a double bed, a dresser, one chair, and the usual stand with a water pitcher and basin. Wearily falling into bed, we found the sheets cold and damp.

Next morning, in his quiet way, George said he would have to make arrangements for our trip to the mine.

“I’ll show you the stores and you can buy some food, not very much, because we’ll have a big order sent up to us,” he admonished.

Order food! I had not the faintest idea about what brands to choose, what cuts of meat, what quantity of anything we would need, but I had to make a start and began at Mr. McAdams’s meat market.

“A steak, a slice of ham, and some lamb chops,” I requested.

“Sorry. All I have is mutton,” said Mr. McAdams. Spotting me as a newcomer he asked my name.

“Miss Fish,” I stated glibly and in quick confusion changed it to “Mrs. Backus.” At his knowing smile I felt my cheeks grow hot with embarrassment, turned and promptly left his store. At Kracow’s I bought what seemed adequate supplies for a few days.

It was still early so I walked on to view Telluride and its surroundings. The streets appeared strangely deserted and silent. Then I saw a hearse approaching slowly followed by two lines of men marching sedately. A funeral, undoubtedly of a prominent member of the community. At store fronts the proprietors stood watching as the cortege wound its solemn way to the small cemetery on the hillside. Thus the men of Telluride paid homage and said farewell to the leading madam of their underworld, in her way the town’s best known citizen.

I continued my walk toward the end of town, half a mile away. The road ran past the mill of the Liberty Bell Mine and a short distance farther to the Smuggler Union, then the little settlement of Pandora where it abruptly ended at the back wall of the canyon.

Partway up the slope, sturdy pines and firs stood proudly in spite of their precarious root-hold in crevices of rock.

Above Pandora, in a rift between the peaks, the deep snows fed a ribbon of icy cold water which, falling to a rocky ledge, leaped headlong into the cascade of Bridal Veil Falls. Now the bordering trees, sprayed by wind-carried mists, were shrouded with tiny glittering icicles while high above soared the majestic spires of Mt. Telluride and Mt. Ajax, magnificent and austere.

The waters of Bridal Veil and nearby Ingram Falls fed the San Miguel River flowing through the gorge it had grooved past Telluride and the plateau to the west, an area containing vanadium ore—rich in radium.

On the trail approaching Smuggler Union Mine.

So high were the walls on the three sides of the valley and so narrow the floor between them that in winter the sunlight reached the little town only a few hours of the day. By mid-afternoon the purple shadows of cliffs dropped a pall over the rugged settlement. Its citizens included respectable miners and their wives, as well as the lawless ne’er-do-wells and their ilk. Near the main street huddled the houses of prostitutes. All night carousing in the saloons and gambling dens was evident from the raucous shouting and cursing. Telluride was only shortly past its wildest days.

Two years previous terror had reigned. Unruly mobs had gathered and rumors had spread that the miners on strike threatened to poison the water supply and blow up the town. A bomb had been thrown at the home of Buckley Wells, manager of the Smuggler. Fortunately, being wrapped in furs and sleeping on his porch, he escaped with no worse injuries than a ruptured ear drum. Although the town seemed quiet now, there remained an uneasy feeling of watchful waiting for further violence. I returned, this morning, to the hotel as though I had been on an exploring trip.