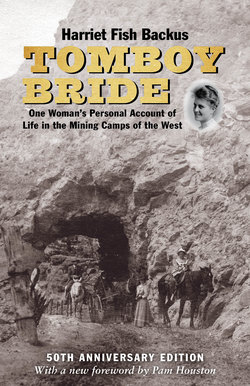

Читать книгу Tomboy Bride, 50th Anniversary Edition - Harriet Fish Backus - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

Fifty feet from our “mansion” was the schoolhouse, closed during the long winter, in session only from May through September when the teacher occupied the house. George had been fortunate in renting it for five dollars a month through the winter with the stipulation that we vacate in time for the opening of the school. No other shack on the hill had been available.

The first morning George began what was to become his foremost daily task—to tunnel a trail to the indispensable “outhouse” which belonged to the school. It was one hundred feet from our back door. A rendezvous of winds from all directions built drifts as high as our heads. Often falling snow filled in the trail as fast as George could shovel it out. Frequently by evening the task began again. Aching with sympathy I could look out the window and tell where my husband was only by the scoops of snow flying over the banks from a source invisible as he neared his goal.

What a transformation had taken place in my dapper young college grad, impeccable in his tailored suits, modern hats, stylish ties, and polished shoes! My snowman wore cumbersome clothes, a black skullcap pulled tightly over his head under a visored felt hat, much too large and hiding his ears, a heavy jacket with turned up collar and sleeves dangling below his leather, fleece-lined gloves, his feet in awkward arctics, drops perpetually dripping from his cold red nose, shoveling a path to the privy.

While eating our first breakfast in our first home, George explained, “The companies object to people on the hill having supplies delivered often because the mules have all they can do to supply the mines with necessities to keep them running. And besides, if they deliver only a loaf of bread it costs seventy-five cents when an entire mule-load costs only a dollar-fifty. Most of the women order only once a month. You’d better make a list of everything you think we will need for a while. Then go across the trail to the stable, just a short distance away, and telephone. Fred Diener has charge of the stable and his phone is the only one on the hill except those in the mine offices. Tell the store you live in the teacher’s house and they will send the order to Ed Lavender’s depot. His pack trains start from there.”

George left for work at the Japan Flora Mine on the slope a quarter mile away. Already longing for his return I sized up our domicile.

The floors of the two rooms were clean but bare. The front room contained a heating stove, the bed, a small table, and one straight chair. The wardrobe was a curtain stretched along one wall hiding the nails on which to hang garments. There was no door between the two rooms. The kitchen contained a cooking range, a small table, two roughly made chairs, and one shelf for dishes. On a small bench in a corner was a tin basin. This was evidently for both dishwashing and bathing. I immediately put a second basin on my list of necessities. Beneath the bench was the “slop jar,” a five-gallon oil can.

One small window in front and back let in a little light in the daytime. One bare electric bulb dangled from the ceiling in each room.

The bed made and dishes washed, I hung our clothes on the wall and my housework was done.

I knew almost nothing about ordering food but we had to eat. We could have nothing fresh sent up, not even milk. That list! How I dreaded to make it! How many cans and of what foods? What sizes? Would I ever learn? My beloved husband was a glutton for meat. I must get plenty of that, and chocolate, which he enjoyed so much. I thought of what my mother used to send me to the store to buy—coffee, salt, butter, and, oh yes, a sack of sugar which came in ten pounds which was always heavy to carry. A loaf of bread was necessary. I had to learn to make my own bread. Mumbling to myself I continued writing. “That’s all I can think of.”

Bundled to the ears I stepped gingerly out into the snow and with mincing steps started to the barn, passing the schoolhouse and a small shack across the trail. A blond, pink-cheeked woman was slowly walking back and forth. Possibly one of the Finns of our community, I thought, and smiling, said, “Good morning.” She didn’t answer but drew her head deeper into the collar of her coat. I couldn’t tell whether she did not understand English or was a shy newcomer. Possibly she felt I was intruding.

The barn was only a short distance away. The doors were open showing five clean horse stalls along each side. In a cubby near the door, feet propped high on the iron belt of a pot-bellied stove, a man sat nodding drowsily but, hearing me approach, jumped to his feet, smiled, and said, “Howdee do.”

“How do you do? I’m Mrs. Backus. My husband works at the Japan Flora and we’ve just moved into the teacher’s house. I was told you would let me use your telephone.”

“Certainly, Mrs. Backus. Everyone uses it. I’m Fred Diener, the stableman for Rodgers Brothers. You came up with one of our drivers yesterday. He went back early this morning.” He pointed to a bewildering telephone on the wall. “You ring five times to get central and,” laughing, “sometimes she’s slow answering.”

On tiptoe I stretched to wind the knob at one side of the box and evoked a timid, tin-panny jingle. After a long wait, I gave the store number. After a longer wait the answer came and my voice sounded strange ordering all that food from my list. With that done I turned to thank Fred and instantly sensed that he was a “diamond in the rough.” My first impression proved correct. He was truly a gentleman, honorable, and a sincere friend to everyone. To have known him was a privilege.

The bald crown of his head shone through a scraggly fringe of sorrel-colored hair framing ruddy cheeks and clear blue eyes of a round, happy face. A moustache, thick and drooping at both corners of his mouth, exactly matched in color his fringe.

Old shapeless clothes, dirty and food stained, reeked of the stable. This tiny room containing the huge telephone was his entire abode: parlor, bedroom, kitchen, and bathroom. In one corner stood an old chair and a small table crowded with used dishes. His meals were cooked on the pot-bellied stove which now was hot with burning coal. The ash container was chock-full and spilling on the floor. On a box in the corner was an old tin basin for washing everything, including Fred. Suspended from the wall by two heavy chains was a replica of an upper Pullman berth, but it never was entirely closed because a mess of faded, worn rags that once had been blankets continually hung down the side of this bunk. As the saying goes, “clothes don’t always make the man,” neither in this case did his surroundings have any bearing on the fine personality of Fred Diener. This thought I carried back with me to our “spacious” two-room hut with its high-peaked roof, a blot like all the other shacks on the limitless white purity of the world about.

The storm of yesterday was spent and the sun on the snow was dazzling. Confident now that I could keep my feet on the trail, I quickened my pace to a point where the whole, vast expanse was a natural amphitheatre. In geological terms, it is called a cirque, formed by the sheer walls of the San Miguel mountains, a spur of the mighty San Juan Range that I surveyed from eleven thousand five hundred feet above sea level.

Without a break in its crest, it curved like a horseshoe from southwest to northeast, two thousand feet above our settlement, an unlimited, smooth-appearing backdrop of blazing white and sparkling as if sprinkled with diamond dust.

The road leading down to Telluride was obliterated by the snow, but I could trace it by the curves of the mountain round which we had ascended. Far beyond spread the lowlands, a vista in white.

My long skirts swishing through the snow, I went slowly home and found the place cheery, the fire still burning. A few minutes later, there was a knock and I opened the door for a lady, carrying a blanket-wrapped baby in her arms.

“I am Mrs. Batcheller,” she announced. Her voice, smile, and manner were charming. “I remember how I felt when we arrived here a year ago, so I came to help you in any way I can.”

“Please come in,” I said, eager to welcome her. “Thank you for coming. I’ll be grateful for your help. I know so little about anything up here that I don’t know how to start. I can’t even cook. Do let me see your baby.”

Only six weeks old, he still seemed very tiny and his face looked thin and pinched. She was nursing him but her abundant milk was not nourishing and she kept in constant communication, she said, with Dr. Edgar Hadley, the leading physician in Telluride who had attended her at Billy’s birth.

Beth BatcheLler skiing on the roof of her house at Tomboy Mine. (Photo courtesy of Telluride Historical Museum, all rights reserved.)

My new friend’s large, beautiful brown eyes and face glowed with health and happiness. She was a picture of loveliness: olive skin, pink cheeks, well-shaped nose, attractive mouth with even white teeth, dark-brown hair piled high on her head. Her capable, graceful hands were used expressively.

We talked about cooking and baking with the handicap of the high altitude, and about Billy, her great joy and concern.

“Come to see me often, won’t you?” she invited. “We’re just across the trail and I won’t get out much until Billy gains a good deal because he must not catch cold.”

I promised, delighted with finding a friendship that was to endure throughout our lives, and eager to tell George about her. He brought work home—many reports that had been neglected during our honeymoon, and since I had taken mathematics and chemistry in college and had some knowledge of chemical terminology, I helped check his figures. He wiped dishes for me. Then we sat at the table checking his reports. (This partnership arrangement lasted throughout the years.)

Suddenly my ear was cocked at the sound of tin pans rattling and banging. As the noise came nearer and louder we laid aside the papers and pencils, wondering what it was so close to our little house. Then in the middle of the ding-donging and rat-atatting came a heavy banging on the house. George opened the door.

“Come right in,” he said. “We’re glad to see you.”

It was a two-man shivaree staged with the noise of an army squad by Johnny Midwinter, the foreman of the Japan Flora, a stubby blond and genial Cornishman, and the mine carpenter, Ole Oleson. They exclaimed over the hot chocolate and toast I served, and I thoroughly enjoyed the mountain tales of these two typical men of the mines, rugged and sincere, artlessly punctuating every sentence with vehement “damns,” “hells,” and “Gods.”

The next day again was sunny. The snow had begun to settle and frost crackled in the crisp air. Some of the chill was gone from my bones. I was working happily about the house and life was all aglow until suddenly, a loud roar shook the place. The roof must be caving in! For one terrified moment my world shattered. I fell limply on the bed, too weak to stand. Instantly the cataclysm was over and I slowly began to realize what had happened. The heavy snow pack on both sides of our steep roof, warmed by the sun and the fire within, had let go with a crash heard far beyond the trail. I understood then why Bill Langley so greatly feared an avalanche!

I was still unnerved and shaking when George came home and suggested taking a walk. I went gladly.

The teacher’s house was the only one on a level area known as “The Flat,” built up by tailings from a mill above that had been discarded. Across the trail, scattered hit-and-miss, were several shacks which had never known paint. Rooted to the ground by small wooden blocks they squatted like setting hens as the deepening snow, even this early in winter, mounted almost to their windows.

Two hundred feet beyond and above the tailings was a level bench on which stood four houses fifty feet apart. A tree standing near one house distinguished it from every other in the Basin.

“All this,” said George, “belongs to the Tomboy. It is one of the richest gold mines in North America. The mill is on a dandy site. It’s a good one and uses the latest methods. The Japan Flora is much smaller and the ore is of lower grade. I am wondering if it can continue operations much longer. The Liberty Bell and Smuggler mines open into such steep slopes they had to build their mills down in Pandora and haul the ore over the trams that you saw as we came up.”

Pointing to a long line running toward the foot of the cliffs he continued: “That long wooden box in the snow covers pipe lines for both air and water. It’s filled with sand to keep the water from freezing. It’s just wide enough to walk along, single file, and miners use it instead of the trail going to the upper workings.”

We walked past the shaft house and I had my first glimpse of a hoist. There was the machinery operating a cage, lowering and lifting men and materials within a nearly vertical opening from the surface to the lowest level of the mine.

The only splash of color in that area was the red junction house of the Telluride Power Company through which came the high tension wires distributing power to all the mines.

We came home to a scanty dinner. We were out of food, and what would happen if our supplies did not arrive on the morrow! I couldn’t imagine. I went to bed wishing there were a corner grocer nearby. At four o’clock in the morning a faint sound like the muffled pounding of a hammer filtered through to my consciousness. I woke George and drawled sleepily, “Dear, what is that noise? I heard the same thing yesterday morning. It seems to be near our house.”

“I don’t know,” he answered. “I’ve heard it too. Perhaps the shifts are changing at the mine. It’s about that time. Anyway, it’s nothing to worry about.” Reassured, I fell asleep again.

Later that morning when I had finished my dab of housework I heard a threshing sound near the door. Opening it hastily I beheld a big mule, heavily loaded, wallowing in the snow. The skinner was tugging at his rope, trying to get him nearer the door while, out on the trail, the other mules of the string stood waiting indifferently.

My supplies! Just in the well-known nick of time. The skinner began dumping boxes in the snow and I gaped in amazement. That sack of sugar which, in Oakland years ago, weighed ten pounds, changed by a misunderstanding in nomenclature to one hundred pounds! Ashamed to betray my ignorance I never mentioned it. Besides, it would cost a dollar fifty to return it. But sugar was not listed on my orders for a long time.

The Tomboy Mill, 1906.

That afternoon I crossed the trail to borrow a cake pan from Beth Batcheller. Six feet of snow covered the trail separating our shacks. As I neared the door I could hear her whistling a cheery tune. Inside that drafty hut I forgot cold, snow, and isolation, for the room glowed with warmth and hospitality. A faint odor of roses came from a potpourri on a small table in one corner. Portraits of her New England ancestors looked down from the rough walls. Old candlesticks held burning candles which brought out the shine in Beth’s lovely eyes and a gleam of happiness on the cheeks of this young wife who was transplanted from a life of wealth and travel to a remote mining camp. Within minutes we were “Beth” and “Harriet” to each other, exchanging family data and events like old friends long apart. The Batchellers were both members of pioneer New England families. Jim, a graduate of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was superintendent of the Tomboy Mill. He and Beth had been married in 1905 in Mattapoisset, Massachusetts, at the summer home of Beth’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. William Deyoung Field. A special train had carried the guests from Boston. We talked until it was time for me to mix the cake I was planning for dinner. Saying farewell she added, “Come over for tea tomorrow afternoon. I want you to meet Kate Botkin. She lives in that house above the tailings, the one with a tree in front. She has been suffering from rheumatism and hasn’t been down for awhile. Her husband, Alex, has charge of the mine office.”

In the snow surrounded by friends, with Beth BatcheLler on the right.

“I’ll be happy to meet her,” I said, unaware how true that remark would prove to be.

The next day over teacups and gleaming silverware I met Kate Wanzer Botkin and later that afternoon, her husband. A graduate of Yale, Alex Botkin was the son of a former Lieutenant Governor of Montana, appointed by President McKinley as chairman of a commission to recodify the laws of the United States.

Kate, the daughter of the chief consulting engineer of the Union Pacific Railway, had lived in St. Paul where she had conducted a private school. They too were married in 1905 and immediately left for the Tomboy, two sparkling persons radiating optimism and good humor. We felt fortunate and, as George said, “we struck it rich” in finding such friends in this remote eyrie.

A few days later Beth asked me again to join her for tea. There were two other guests that day. Mrs. Rodriguez, a frail Mexican girl, had coal-black hair and olive complexion, deep brown eyes with a melancholy expression, and hands roughened by hard work. She and her husband, a miner, lived in one of the houses clustered near the tailings flat.

And there was Mrs. Matson, a chubby woman from Finland, blond, rosy cheeked, and lively. With nine mouths to feed on a miner’s wages she helped lay washing and ironing for others and that morning had returned the laundry she had finished for Beth Batcheller.

The beautiful silver tea service was in use again. Beth poured tea and served cake with the grace and graciousness of a hostess in a mansion of luxury. I listened to their talk carefully for every bit of information I could glean concerning the problems of living at an altitude of 11,500 feet. Indeed there were problems and I rapidly became aware of them.