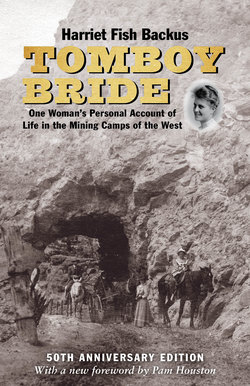

Читать книгу Tomboy Bride, 50th Anniversary Edition - Harriet Fish Backus - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 6

When the storms and bitter cold of March were upon us, we learned that a shack on the bench above the tailings was to be vacated. The school teacher would need her house shortly so we thought it wise to get settled permanently.

It was customary for those leaving the hill to sell their meager furniture to the new occupants, usually a so-called bed, a table, chairs, and stoves priced from thirty-five to seventy-five dollars. We bought the outfit from our predecessors for seventy-five dollars and moved into our “furnished” home.

The view was superb. On three sides the great white range of mountains stood close like a surrounding guard of honor and we could look down the deep canyon as it sloped off into the valleys toward the horizon.

Our entrance porch was made of three rotting planks weakly supported by a six-inch-thick log on the down side. Squatted flat on the ground unpainted, like all the other shacks, it measured twenty-two feet by ten feet in size and was built of one-inch boards with battens, but no lining whatever. It was divided into three sections by partitions with doorways lacking doors. Between the front and rear sections, our parlor and kitchen each eight feet deep, a six-foot sleeping compartment was literally squeezed in. A small window on each side of the front room and one in the kitchen supplied daylight. The middle or bedroom had no window, but from the middle of its rough ceiling was a long cord and a small electric light bulb which could be carried into the front or back rooms to light the darkness. This room contained only a double couch. There was no space for a dresser—even if we had one. The only daylight came through the doorways.

In the depth of winter, our shack is faintly seen at extreme right. The range on the left is part of the 13,000-foot cirque surrounding it.

The “parlor” consisted of a pot-bellied stove in one corner, a single mattress on legs, and two chairs, one of which was made of three twelve-inch-wide boards painted black.

The kitchen seemed larger only because there was no ceiling to hide the rafters. A large coal range, a small table, two chairs, three narrow shelves on the wall completed our kitchen equipment, except of course for the tin basin in its stand with the utilitarian five-gallon can beneath.

Yet, more accessible than at the teacher’s house, the important outhouse was only fifty feet from a decrepit lean-to attached to the kitchen, less than half the distance George used to shovel snow.

The flooring of our shack was of ugly, splintering planks. Something had to be done about that! At least in the “parlor.” With blue denim, brought up from Telluride by the faithful mules, we nailed our “carpet” over a padding of newspapers, then we went to work on the walls. They were rough-surfaced boards impossible to paint. George got enough blue building paper to line the entire house, tacking the paper to the boards and over the narrow ledge that ran horizontally around the walls three feet above the floor.

The snow was too deep for the mules to climb to our shack so our sacks of coal were dumped near the main packed trail, two hundred feet away. The labor George was saved digging to the privy was more than doubled carrying coal four times the distance. Every night when it was time for him to come home I watched until I could see him start up the trail with a hundred-pound sack of coal on his shoulder, propped the door open for him, and turned and dashed to the kitchen in order to avoid seeing him at this Herculean task. I couldn’t bear to watch and suffered with him all the way. If one foot slipped from the icy ridge, he would sink deep into the feathery trap, sometimes able to hold fast to the sack of coal, but more often it would slip from his grasp and only with strenuous effort could he lift it from the snowy depths and start again. And that was not all!

Water was as precious as on a burning desert and in winter the mine company’s most serious problem. The only available source was at the summit of the range, beautiful Lake Ptarmigan, named for that bird of high altitudes that changes its dark summer plumage to white in winter. The lake was small, its capacity limited. The amount drawn for running the mill and all other uses must not exceed sixty gallons per minute. Consequently, not a drop could be wasted. Besides the coal, George had to carry water from the shaft house four hundred feet away. A five-gallon oil can on his shoulder contained our entire daily supply. Fortunately the can had a screw-on cap because often George slipped off the trail and not a drop could be spared. We longed for the day when a frozen spring behind our shack would thaw. This natural source of supply was the only luxury our friends envied.

On about the same level, ninety feet away, was “Cloud Cap Retreat,” the home of the Botkins and their pride and joy, a great Dane named Thyra. Sometimes Alex would walk three quarters of the mile uphill to have lunch at home, taking Thyra back to the office with him. A little later she would come bounding back with Kate’s mail in her mouth, her beautiful head held high above the snow to protect the package for her beloved mistress.

Except for two houses at the upper workings, our shack was the highest. I could see the panorama below, miners walking the pipe lines, riderless horses returning to the stables, occasional skiers catapulting down the opposite peak, packtrains on their wearying journeys—fascinating scenes indelibly etched on my memory.

Most horses in the Telluride district were owned by Rodgers Brothers. In the town the main stable housed fifty, with a small barn at the Tomboy. Day and night, summer and winter they were ready for hire. Riders, experienced or not, distances to be traveled made no difference. On reaching his destination the rider tied the reins to the pommel of the saddle and turned the horse loose. Regardless of the distance, knowing the trails far better than most riders, the horse quietly and surely returned to the nearest stable, at the Tomboy or in Telluride. In winter they went directly to the barn. In summer they might wander awhile, seeking tufts of grass. A riderless horse was part of life in these mountains and no cause for concern.

How I loved them! Never did I lose the pleasure of knowing that with an affectionate pat I could dismiss my horse confident that he would return to his barn with the certainty of a homing pigeon.

And how my temper blazed when I saw a horse slowly approaching the end of the trail, head drooping low, flanks dripping foam, for I knew what it meant—a miner in a hurry!

We had several favorite horses. Chief, a gentle handsome chestnut with lighter tail and mane, somewhat heavy and not so fast but reliable, a woman’s horse, and safe for beginners, could always be depended on to take his rider smoothly and safely anywhere; Fanny, more slender though not as handsome as Chief, a mottled, reliable roan; Bird, slender and spirited, ready to jump at anything but as comfortable to ride as a rocking chair. Poor Bird, strained by drunken riders who unsparingly ran him up miles of steep slopes, a bundle of nerves, never permitting another horse to pass, running as if to avoid the lash. And King, tallest of them all, a raw-boned rangy horse able to cover ground in long strides.

Horses were used to haul heavy machinery, lumber, and mine timbers on sleds in winter and wagons in summer, usually six to a team. Frequently in winter it took three days to cover the five and a half miles from Telluride with horses and men laboring through the daylight hours to break through drifts on the way to the mine. A rate of a mile and two thirds a day!

Our method of moving.

Only by horses were we able to go up or down the mountains, but the daily existence of those on the hill depended upon mules.

The pitiful patient mule! Fury still burns within me when I recall the cruelty and abuse that animal endured. An interesting book, Early Western Travels, 1778 to 1846, edited by Rueben G. Thwaites, gives a short account and pleasant tribute to that long-suffering animal: “At that date the mule traveled hundreds of miles, carrying unwieldy burdens weighing three or four hundred pounds. Due to exposure and lack of care, the mules often suffered from swollen legs and feet and then, unable to go farther, were beaten and dragged and if still unable to move were left by the trail to die.”

In 1906, in the San Juans, the mule had some care, to be sure. His day was one of regular hours. He traveled a beaten trail. He was well fed. But with all that his condition was not much better than the author described in Early Western Travels.

All freight for the Tomboy was sent to sheds in Telluride. Freight included everything used in the mines, mills, boardinghouses, and shacks: bedding, towels, shoes, potatoes, sugar, beef, pipes, shovels, tools, blasting powder, and lagging. Led by a skinner on horseback, fifteen big raw-boned mules formed a string. Each skinner loaded his own string, weight, balance, and security being the paramount necessities. A large pad afforded some protection although too often the mules’ backs were chafed and bleeding. Over the pad a wooden cross-saddle was held securely by a cinch around the mule’s belly so tightly drawn by a ladigo that the belly was often compressed many inches and the animal shaken to his very hooves, causing great discomfort. Yet, this was necessary to prevent the heavy pack from slipping which caused more chaffing and could be very dangerous. A side load was lifted into place and firmly secured by a rope deftly thrown and tied. The mule sagged lopsidedly until counterbalanced by a load on the other side roped securely by a flip of the skinner’s hand. The third load was thrown on the back, and ropes crossing from side to side lashed everything together.

The most unwieldy burdens were large crates and boxes. The total weight could not exceed three hundred pounds but bulk made the load difficult. A still more awkward load was lagging, often twelve feet long, lashed on both sides, reaching high above the mule’s back, the ends dragging beyond his heels.

From our peak I could often spy a string of tiny specks, like ants coming out of the tunnel, black against the snow, disappearing in the Big Bend of the mountainside to reappear later, larger, nearer and higher.

No less rugged was the skinner, bent low over his saddle. His face was almost hidden under the wide, turned-down brim of his slouch hat.

Rhythmically he slapped his long arms against his sides to ease the numbness from a mountain blizzard. His body was a shapeless hulk under layers of heavy shirts and jackets. Long gauntlets and heavy boots were fur-lined protection from frostbite. Sheepskin chaps, leather-fringed from ankle to waist, were held in place by a wide, metal-studded belt. For emergencies an iron shovel was strapped to one mule and a long, heavy coiled rope was looped around the saddle of his horse.

Passing a string of mules a rider always took the inside of the trail, and in winter, when snow narrowed the path, he threw both legs over the saddle toward the bank lest they be crushed by a packload rubbing against them.

The load of an entire string might be destined for the mill, or storehouse, at the mouth of the Cincinnati Tunnel, or to the boardinghouse. In winter the strings could seldom get up to the “Upper Workings.” Sometimes one mule was loaded with small orders for different families, a cause of annoyance and delay because often an entire load must be removed to find a single package. If it was possible to reach a cabin the skinner would detach and lead a mule from the string. But more often in winter the orders were dumped in the snow along the trail and we had to tramp down the snow or dig into it groping around to find our packages.

While the skinner made the deliveries the mules enjoyed a short, well-earned rest. Unloading was done as skillfully as loading. A twist of the rope released the top pack. The side loads were removed and the mule rose up like a ship lightered of cargo. The skinner’s horse knew instinctively when to step forward to advance the string for unloading the next in line.

Immediately after the string was unloaded it was reloaded with three one-hundred-pound sacks of mill concentrates destined for the railroad station in Telluride for shipment to smelters. The afternoon trip then started. At day’s end, often seven in the evening, the mules had covered more than twenty miles, ten of exhausting ascent. During storms it took all day for one round trip. At times the skinners gave up partway up the trail and returned to Telluride with their loads.

The mules! Large, gentle, patient pictures of dejection, trudging along, heads sagging, ears flapping to shake out the needle-sharp particles of ice driven in by howling winds. Packs cutting deep into their backs and irritating large running sores, forelegs and ankles swollen with rheumatism to twice normal size! Through four long winters I shuddered with indignation and pity at sight of their suffering.

“Stubborn as a mule” is a phrase of meaning to a skinner. Day after day the mules plodded through their unbroken routine, but if one fell—it was a different story. Urged by the skinner, he might try to get up, sometimes succeeding but mostly not. If he failed, the skinner had to unload him. If one mule fell, the entire string was knotted. The short, connecting rope jerked the mules in front and the fallen one behind, and the others restlessly twisted this way and that until finally there was an entangled mess of mules falling like tenpins. Quite often one rebel would lie down deliberately while the skinner wrestled with another.

But stubborn as mules are, my anger leaped to white heat whenever I saw how an obstinate or possibly helpless mule was sometimes mistreated. Then came the measure of the skinner’s temper, brutality, and his command of profanity. At first he might coax, then he swore. “Swearing like a mule skinner” in the mining world means the most vehement, vile, profane, and obscene maledictions invented. When strong language brought no response from the mule, often stuck deep in the snow, the skinner kicked him with his heavy boots or lashed him brutally with a strap. The mule might lunge feebly, and settle down again calmly, perversely. Then the enraged skinner resorted to the iron shovel—banging it on the animal’s head.

Though I had been warned that it only infuriated a skinner to berate him, I often rushed through the snow and in my kind of violent but less evil anger called down vengeance on his head! Pausing only to cast a withering look at me, he would turn back and the deadly “thud, thud” of the shovel on the mules would begin again. Only when he was ready would Mr. Mule struggle to his feet, if possible.

Accidents to the mule strings were bound to happen in that rugged country. During our sojourn a mule loaded with boxes of deadly blasting powder fell from the trail into the gulch. Fortunately he landed in deep, powdery snow which cushioned his impact and he was dragged safely back to the trail.

A year before four mules, loaded heavily, fell over a deep cliff. Rescue seemed impossible so no attempt was made to extricate them. This could be the fate of a mule at any time on those trails.