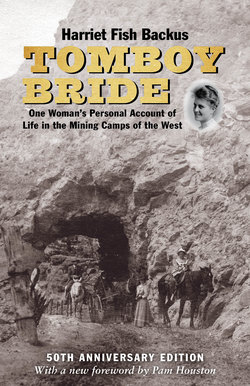

Читать книгу Tomboy Bride, 50th Anniversary Edition - Harriet Fish Backus - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

“The sled will be here at ten o’clock,” George informed me. “Wear your warmest clothes. It’s a long, cold ride. And let’s eat again because we may not reach the mine until late afternoon.”

Bundled in a dark-blue wool dress with red piping on the collar and cuffs, a full ankle-length skirt, two petticoats and tights to keep my legs warm underneath, fleece-lined gloves, a soft, black sealskin cap with earflaps, surely I would never feel cold. George was equally bundled in his woolens, and under his hat a stocking cap covered his ears.

It was snowing when the sled arrived. Bill Langley, the driver for Rodgers Brothers’ Stable, tall and rugged, looking huge in a long, heavy mackinaw, greeted us.

“Good mornin’, folks. Sure hope you’re dressed warm. Ever been in the mount’ns before?”

“I haven’t,” I said, “and I’m overwhelmed by the grandeur.”

“Wonderful country, this here,” he agreed and tucked a heavy fur robe around George and me as we snuggled close together in the back seat of the sled. Wrapping himself in a fur robe, Bill gathered the reins, slapped the horses on the rump and soon I was to enjoy my first sleigh ride.

We turned off the main road at an easy trot and glided straight toward the foot of the mountain only a few hundred yards distant. The road clung to the rock wall, zigzagging back and forth around ravines and overhanging rocks. I grew tense. The horses slowed to a walk as the increasing altitude made breathing more difficult. Steeper and ever steeper we ascended, and deeper plunged the gorge beside us. An occasional glimpse was all I dared take. Only a few inches separated the sled from the menacing drop below. I kept my gaze on the peaks beyond the canyon and the wall of rock we skirted within arm’s length. George explained the clicketyclack that we heard was the sound of ore-laden buckets passing over supports on the tram towers that carried the cables.

The Tomboy in the basin with twenty feet of perpetual snow on the peaks.

Biting cold began to penetrate our wrappings. My toes and fingers were getting stiff, and there was a long pull ahead with no turning back.

“We’re near’n a spring where I water the horses,” Bill drawled. The poor things were panting, their nostrils puffing in and out like a bellows. As if understanding that word “water,” the animals swung the sled so sharply that it grazed the edge of the abyss. In the bend of a hairpin turn they stopped, aware that this was their last chance for a drink on the long pull. The road was covered with ice as was the spring.

Unfastening an axe from the side of the sled, Bill cautiously inched his way across the sheeted ice and began chopping the mouth of the spring.

“This is the most treacherous spot on the road,” he told us, “ ’cause ye see, when ya get down to the water there, some of it always spills over and freezes. Gets mighty slippery for the horses.”

With their heads lowered, the jaded animals patiently waited for their refreshing drink. When again we were moving, I clutched George’s hand tightly for reassurance.

“We’ll soon be at the tunnel,” Bill assured us. He knew intimately every quirk of every bend along this ledge that had been hacked from the mountain walls. Just where it jutted out on a shelf overhanging the canyon, we swerved into a tunnel, cut through solid rock. It was a curved archway, thirty feet long, barely high enough to miss the heads of the horses or loaded pack mules.

As we emerged, the awesome grandeur burst full force upon us and almost took my precious breath away. Far across the gulch, the jagged heads of giants pierced the leaden sky. Pointing with his whip toward the mighty pinnacles, Bill asked, “Ma’am, can ya see that basin a little ways down the slope of the farthest peak, up high there, near the top? Well, there’s a little settlement there where you’re goin’ to live.”

George let Bill do the talking because this was his home. These were his beloved mountains and pride in them glowed in his eyes and warmed his voice. More traveled men than Bill Langley had been spellbound by their magnificence. H. H. Bancroft, great historian of the West, had written in the phrases of yesteryear about the spell cast by mountains upon nature lovers.

“Nothing interests many of us like the mountains which will always draw men from the ends of the earth that they may climb as near to Heaven as may be, by their rocky stairs.” Of these San Juans he wrote, “It is the wildest and most inaccessible region in Colorado, if not in North America. It is as if the great spinal column of the continent had bent upon itself in some spasm of earth, until the vertebrae overlapped each other, the effect being unparalleled ruggedness and sublimity, more awful than beautiful.”

These vertebrae of the monster included the giants Uncompahgre, Wetterhorn, Red Cloud, Sneffles, Wilson, Sunshine, Lizard Head, each one higher than fourteen thousand feet, soaring to heaven like spires, and surrounded by peaks of eleven, twelve, and thirteen thousand feet. They held our gaze through snow falling in large soft flakes, fuzzing our faces, whitening the robes. Trees were sparse and scrawny. Shrubless expanses prevailed. We had climbed to ten thousand feet but the grade was less steep, a great relief to the horses and to me because I suffered, hearing them panting for breath and seeing their flanks heaving with each step. Entering the Big Bend, as it was called, they picked up speed as though anxious to reach journey’s end.

Part of the surrounding range, including the Big Elephant slide.

But the relief of this half-mile curve ended as we entered Marshall Basin where the only settlement was Smuggler, a cluster of shacks that boasted the “highest Post Office in the world.” It was housed in a tiny store which, with a blacksmith shop and the upper terminal of the tram, perched precariously on a ledge overhanging a chasm that formed the outlet of the Smuggler Union Mine. Just above the boardinghouse was the tunnel through which ore from the mine was loaded into the tram-buckets. As the sled glided silently past, we heard the rattle of buckets starting their downward journey over the depths from which we had just climbed.

Snow fell heavily from the darkening sky. The horses tugged and strained to break through the soft encumbering fluff into which they sank deeper and deeper. Patient until now, Bill began urging them on through the blinding white drapery of snow. We could sense his foreboding of trouble ahead. The team made little headway and presently stopped. Leaving the sled, Bill forged ahead and after a long time, returned, plodding waist-deep through the snow.

“A stroke of luck for us, folks,” he said, scooping snow from his face with a heavily gloved hand. “If we had got here a little sooner it would’ve been the end of us. Part of that damned Elephant has slid. That’s the Big Elephant just ahead. Worst thing in the San Juans! Look at that slope. It’s steep, steep as hell! Snow piles up on the peak, gets so heavy it can’t hang on then lets go all of a sudden. My God! Talk about cannons, what a roar! Nothin’ worse than an avalanche. Got to watch the cussed things all winter. If any more snow had come down, we couldn’t have got through tonight, fer sure.”

Through chattering teeth I asked, “How can we get through?”

“Oh, the Tomboy’s already sent a crew to shovel enough away fer the packtrain that’s stalled on the other side. We’ll jus’ have to wait. No room to turn ’round and you can’t walk back to Smuggler without snowshoes. Four years ago we had a dev’lish winter. Snow was deeper than usual and lots of horses an’ mules got lost. One Feb’ry morning the snow on a peak in the Coronet Basin let go right over the Liberty Bell boardin’house. Son-of-a-gun buried everything, house and men. When the call came to Telluride, we organized a crew an’ got here fast as we could. Stationed a man to watch the mountain and at the sight or sound of a crack in the snow, he was to fire a warnin’ shot.” He continued, “Men from all the mines was there and we dug like crazy. We dug a few fellas out alive when the lookout fired. He’d heard a crack but a damn avalanche from the other side had broke loose. I don’t know how any of us got out alive—some didn’t, that’s fer sure. You never know jus’ when them dern things is comin’ or where they come from or what they’re gonna do. I’m scared as hell of em!” With increasing vehemence he finished his story and left me also “scared as hell.” I squeezed closer to George, imagining the horror of suffocation in the deathly embrace of the beautiful white fluff. Historians have told that near this very range John C. Fremont, the “Pathfinder,” in 1848 lost nearly all his men and every one of his mules froze to death.

The struggle to get supplies up to the Tomboy after the trail had been partially dug out.

A faint tinkling sound of bells penetrated my fearsome thoughts. Bill grabbed the reins and urged the horses deeper into the snowbank on the inner side of the road.

“She’s open,” he said, “but we better stay here. Too risky to pass mules in a storm. Too big a chance of them fallin’ into each other and some being knocked over the drop. Mules always have to take the dangerous side. They learn by experience how to avoid the edge by feel of the trail.”

A horse and rider, half-buried in snow, wallowed toward us within inches of the sled—so near that I dodged. Roped behind the horse was a huge animal, the lead mule, his head down, loaded with a pack that would have been too ponderous on a smooth road in good weather. He was followed by others, equally overburdened and linked by ropes from their halters to the saddle of the mule ahead. Lunging, pulling back, struggling forward, snorting from the effort to keep up with the mule ahead, the poor brutes inched onward until the last of a string of fifteen passed us and the tinkling of their bells was muffled in the deadening silence of the snow.

Through the path that had been shoveled for the mules the snow was still belly-deep on the horses and the Big Elephant loomed ahead of us. Fighting the uphill pull the tired horses tottered against each other, obediently lunging as Bill shouted at them, tugging valiantly until finally we had passed the danger and could see a dim but welcome light ahead.

“That’s the only store,” said George. “It’s run by a fellow named Fyfe, known as Scotty. All he carries is supplies for miners: shirts, cords, overalls, gloves, overshoes, stamps, and a little writing paper. But everyone depends on him because he rides down to Smuggler every day he can get through to bring up the mail.”

As we passed the store a dull, heavy, continuous “thud” was growing louder.

“That’s the voice of sixty stamps in the Tomboy Mill,” George explained. “And it’s a noise mining people like to hear. It never stops unless there is trouble.”

We slipped past the brilliantly lighted buildings of the mill and began the last half mile of our trip, climbing past scattered huts to stop in front of a tiny shack peeping above the surrounding white expanse without a visible path leading to it.

“Home,” said George with a happy smile. I forced my stiff legs out of the sled and sank up to my waist in snow. It was a frightening surprise to step suddenly into what seemed like a bottomless hole of white down.

“You’ll get use’ t’ that,” Bill said, grinning.

George rescued me and we ponderously made our way to the door of the shack.

“It was a wonderful ride,” I called to Bill Langley. “I’ll never forget it.”

“G’bye,” came his reply. “Fer a tenderfoot you’ been mighty brave.” And he headed his horses toward the barn.

George opened the door of our first home. The square entry was barely large enough to get inside and manage to close the door behind us.

We entered a room ten feet square which was the living room and bedroom combined. Beyond it was the kitchen, same size. That was all!

From a woodpile in a corner of the kitchen George started a fire in the cooking range. We made toast and hot chocolate with a few cooking utensils already there. After satisfying our stomachs with this small repast, we eagerly fell into bed, utterly exhausted. Our bed consisted of a mattress supported by springs with legs attached, and our blankets were borrowed from the bunkhouse of the Japan Flora Mine. This unpretentious setting was the beginning of my housekeeping duties.