Читать книгу Walk Like a Mountain - Innen Ray Parchelo - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Walkers are also ruminators. Not that we chew grass, our cud is usually some random thought or narrative that floats around like the kicked-up dust from the road. Some years ago, during one of my walks down whatever country road happened to be close to home, I began to ruminate over what seemed like a minor mystery in my understanding of the Buddha-way.

I recognize that the Buddha-way is not the narrative that floats around many walkers’ minds, but it does mine, mostly because of the personal and professional interests that have occupied me for a long time. Personally, I have studied, practised and taught the Buddha-way within several traditions since I was an older teen, more than forty years ago. Theravada, the two flavours of Zen and most recently Tendai and Pure Land, have been the vehicles carrying me towards the other shore. This has culminated in my ordination as the first Tendai priest in Canada and my continued development of Tendai in Canada, primarily through the Red Maple Sangha I founded in 2002.

Like a true Gemini, I jump between two parallel and often intersecting paths. In addition to my Dharma-path, I have been a social worker and community developer for thirty-plus years, almost exclusively in the rural communities of Eastern Ontario where I have found my homes and walking trails. Over that time I have watched with delight and some concern as Buddhist practice, especially vipassana-style mindfulness, emerged as an important modality in the securing of mental health. Since the appearance of the earliest treatment model, called Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR), movement practices like walking have come to occupy a regular, if minor, position in the inventory of mindfulness skills.

About the cud, my mystery: very simply put, we know the Buddha got up from his seat under the Bodhi tree and stepped into religious history. He walked across North India and established a monastic order that walked with him. His birth story distinguishes him by his three steps. As a mature and troubled adult, when he left his palace he walked into the forest and walked for decades with a group of fellow renunciants. His early symbol was his foot-print (padakan). And on and on. The question that rolled around in my walking thoughts and led to this book has to do with the apparent relegation of walking as practice, as cultural image and as aspect of religious history to a minor role or even to be dismissed as unimportant. When I tried to imagine the Buddha’s time, or that of Jesus or Moses or any other religious leader, when I imagined them walking for days and months as they shared their teaching, it seemed without question that some major teaching and practice would have happened along the way. It seemed without question that this walking experience would have played a key role in the cultivation of contemplative life. And so I wondered why it wasn’t explored in great detail in subsequent literature or teaching.

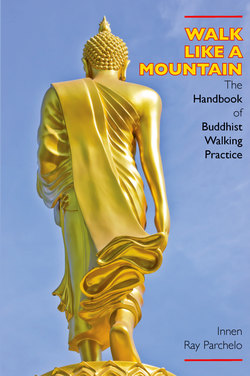

Initially, I imagined a magnum opus, a wise and scholarly tome that examined images of foot, walk and path in the most obscure Indian and Chinese texts, that traced the teaching tradition across all schools. That may one day be written. However, in the end, the practical side, the walker, won out. Hence this book, which is not the scholarly tome but a handbook. It takes you on a journey; it shows you how to transform the ordinary act of walking into a beautiful and energized contemplative act.

I think it was my friend Greg Krech who tells his story of walking a trail in his Vermont neighbourhood. He recalls walking up the trail and grumbling at how rough and untended the trail was. He slipped into blame and resentment at the poor quality of the path. Once at the top, he recognized how collapsed his mind-state had become and approached the descent with a perspective open to gratitude. Walking the same trail he saw all the evidence of hundreds of person-hours which had cleared branches, restored the ground and protected precious plants. In his haste and selfish-mind he had missed all the evidence of other hands.

Now that I have completed my journey, may I acknowledge the many hands involved in clearing the way for this project. Once more, I thank my parents and my walking-mentor, Ray Lowes, for introducing me to the trail so early in my life. I thank my precious friend and educator, Dr. Nalini Devdas, who opened my Dharma-eye and has always insisted on thoroughness and persistence in writing and study. I thank my sensei, Rev. Monshin Paul Naamon, Secretary General of the Tendai-shu North America District, who helped me learn many of the walking practices described in this book and in so many other ways. I thank all the writer-practitioners of the trail who have helped me to understand the source material of the book. I owe special thanks to Thomas Tweed for his notion of religions as “crossing and dwelling”, to China Miéville for his imagined world of in-between/un-seen spaces. I thank my publisher, John Negru who planted the seed of this book and helped make it a reality. I thank my wife, Judy LeClair who encouraged me to write and bore my absence and solitude with such understanding and patience. I thank my beloved four-legged trail-companion, Joshu-daiosho who brought me back to the trail so many times. I thank all my human trail-companions, those who have walked with me, short trail, long trail, winter, summer, all over the world. I bow to all my fellow walkers and un-official henro-pilgrims who have kept up the drumbeat of steps on the Earth. They remind me of dogyo ninin, we never walk alone. Last, but hardly least, I bow and offer thanks to Jizo-bosatsu, the Bodhisattva of the road. Even before I knew his name, he guided me along every trail, calling me forward, urging me to risk another step. To him, my constant road companion, I offer up whatever merit may arise from this book and every step taken along the way. Om namu jizo busa.